On the way to the great Burgundy vineyard

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

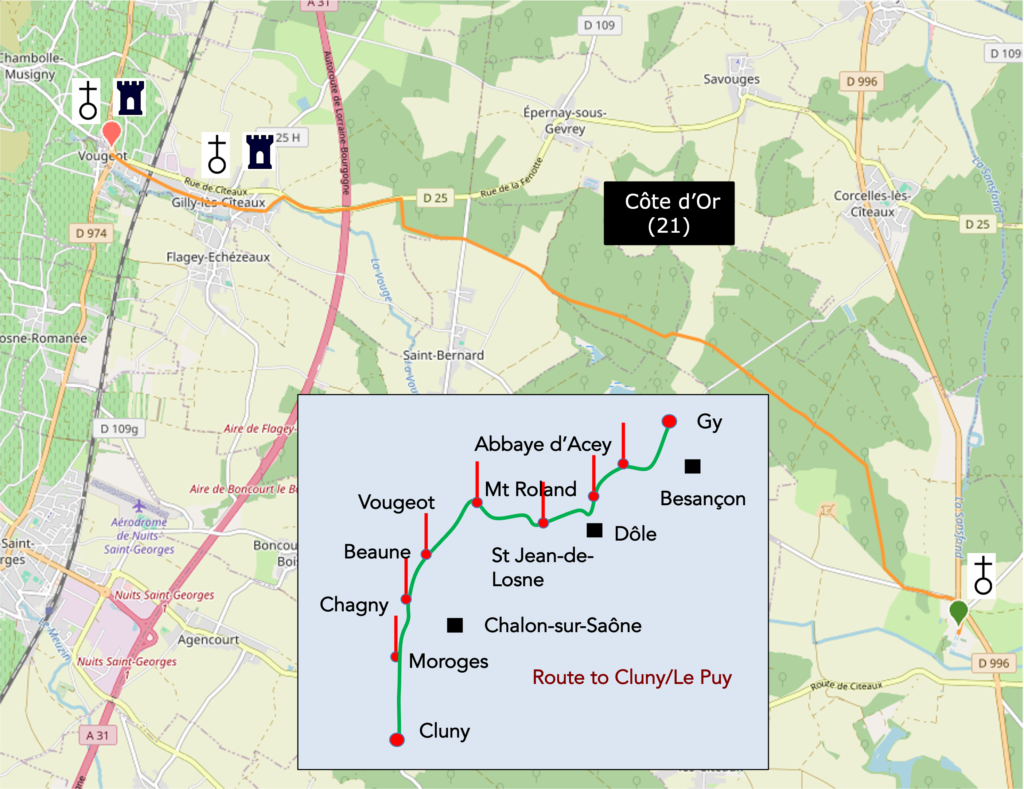

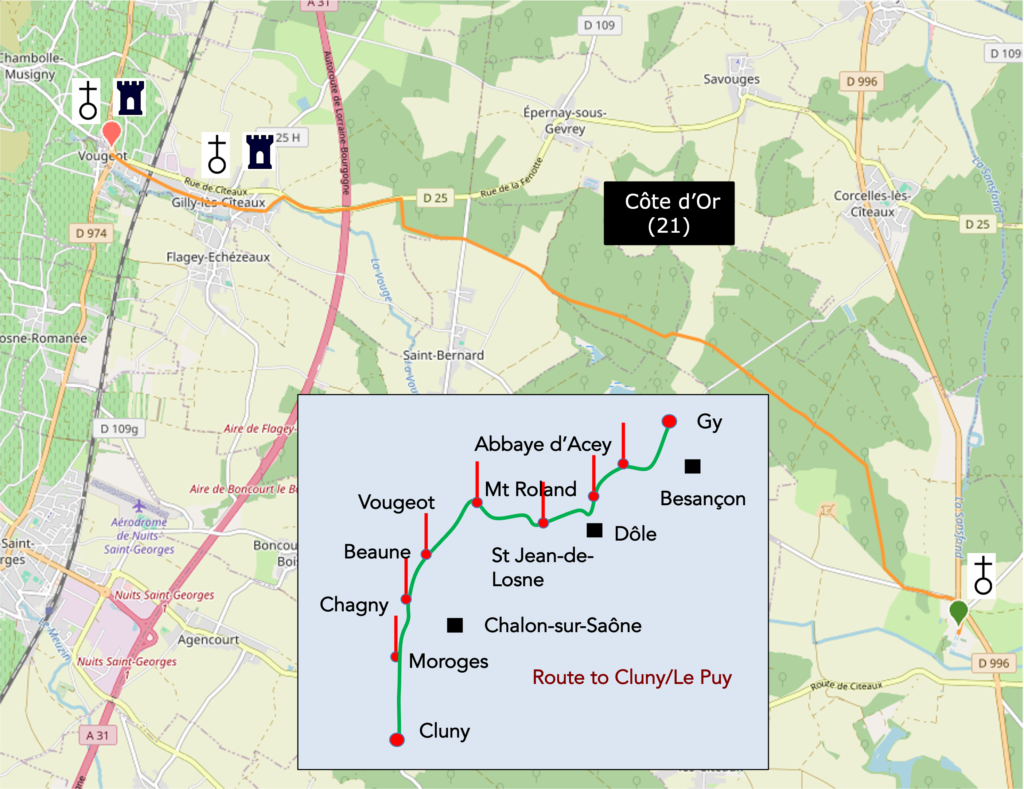

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

| This is obviously not the case for all pilgrims, who may not feel comfortable reading GPS tracks and routes on a mobile phone, and there are still many places without an Internet connection. For this reason, you can find on Amazon a book that covers this route.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page. |

|

For many people, Burgundy is summed up by its vineyard, so strongly does it embody the soul and renown of the region. From Dijon to Beaune, and far beyond, stretches a chain of villages, enclosed vineyards, and hillsides shaped by centuries of patient labor. This is the realm of the Route des Grands Vins, that ribbon winding between hills and valleys, linking names that resonate like promises: Gevrey Chambertin, Nuits Saint Georges, Pommard, Meursault. Each stage is a pause within a landscape shaped by human hands, where the vines unfold like a checkerboard of gold and green, following the light and the seasons. Some of these lands are listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites. They are far more than a terroir. They are a living inheritance, passed down from generation to generation. The Burgundy vineyard is not merely a geography, but a culture, a way of inhabiting time and land, an intimate encounter between soil, vine, and the winemaker’s hand.

But before reaching the heart of this wine growing kingdom, before the prestigious names engraved in the memory of wine lovers appear, other landscapes must be crossed, more discreet yet just as essential. Fields of wheat, meadows punctuated by hedgerows, and large groves casting shadows at the bends of the paths form the outposts of the vineyard, lands that announce it without yet revealing it. They will allow you to reach Vougeot, the beating heart of wine growing Burgundy. There, suddenly, the landscape changes. Hillsides clothe themselves in a checkerboard of orderly vines, enclosed vineyards appear behind low stone walls, and you enter a world shaped for centuries by the patience of monks and winemakers.

How do pilgrims plan their route? Some imagine that it is enough to follow the waymarking. You will soon discover, however, that the waymarking is often deficient. Others use guides available on the Internet, which are also often too basic. Others prefer GPS, provided they have imported the Compostela maps of the region onto their phone. By using this method, if you are an expert in GPS use, you will not get lost, even if the proposed route is sometimes not exactly the same as the one indicated by the scallop shells. You will nevertheless reach the end of the stage safely. In this regard, the site considered official is the European route of the Paths of Compostela (https://camino-europe.eu/). On today’s stage, the map is incorrect. With a GPS, it is even safer to use the Wikiloc maps that we provide, which describe the currently waymarked route. But not all pilgrims are experts in this type of walking, which for them distorts the spirit of the path. You can therefore simply follow us and read along with us. Every difficult junction on the route has been indicated, to prevent you from getting lost.

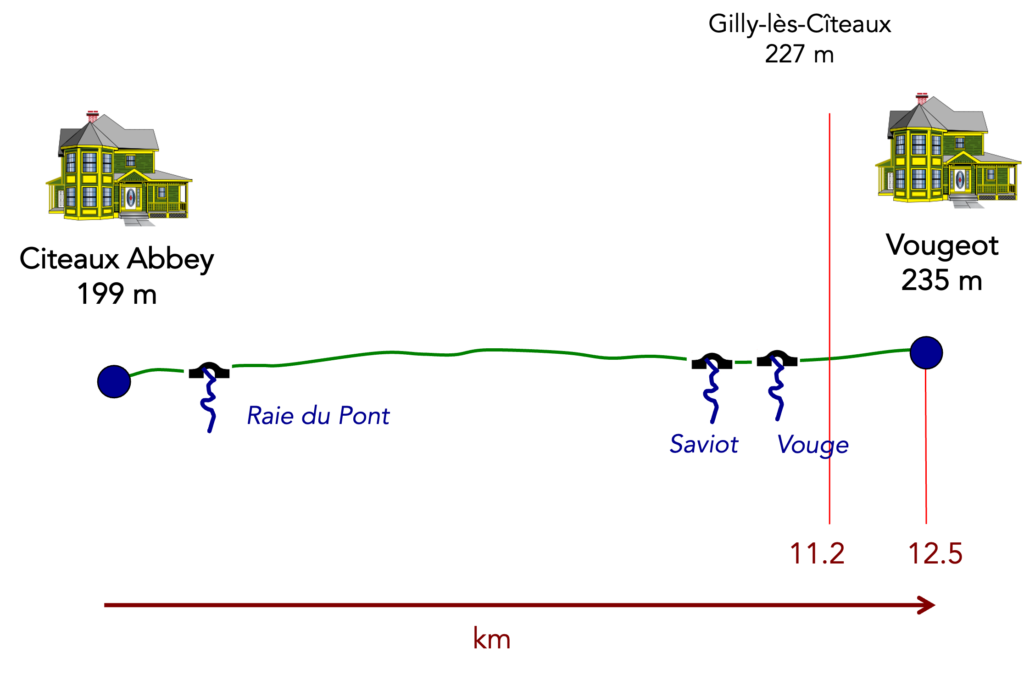

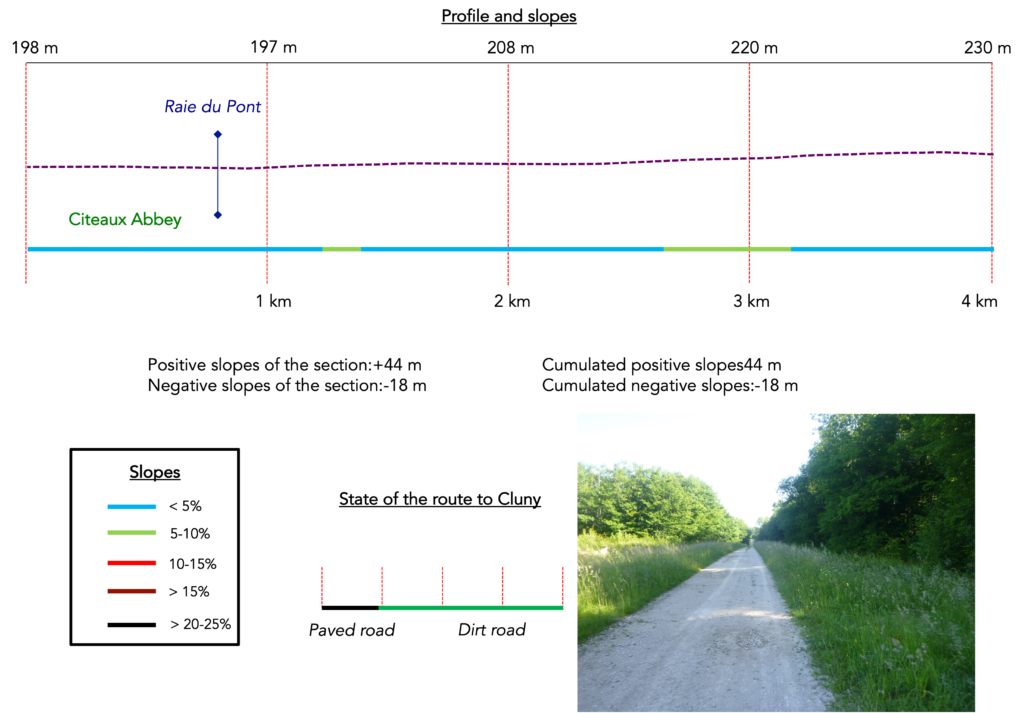

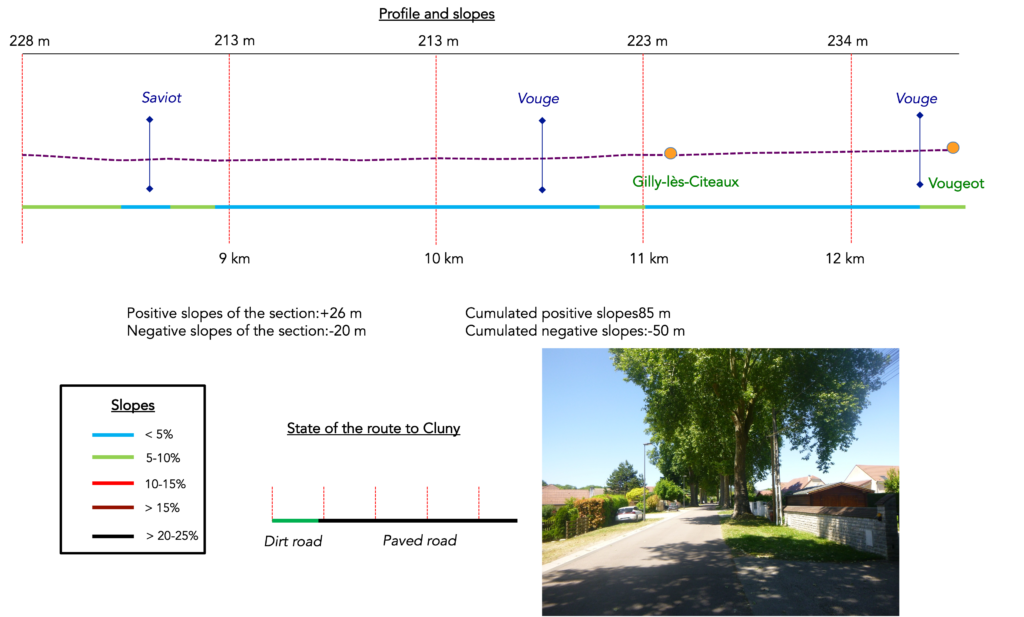

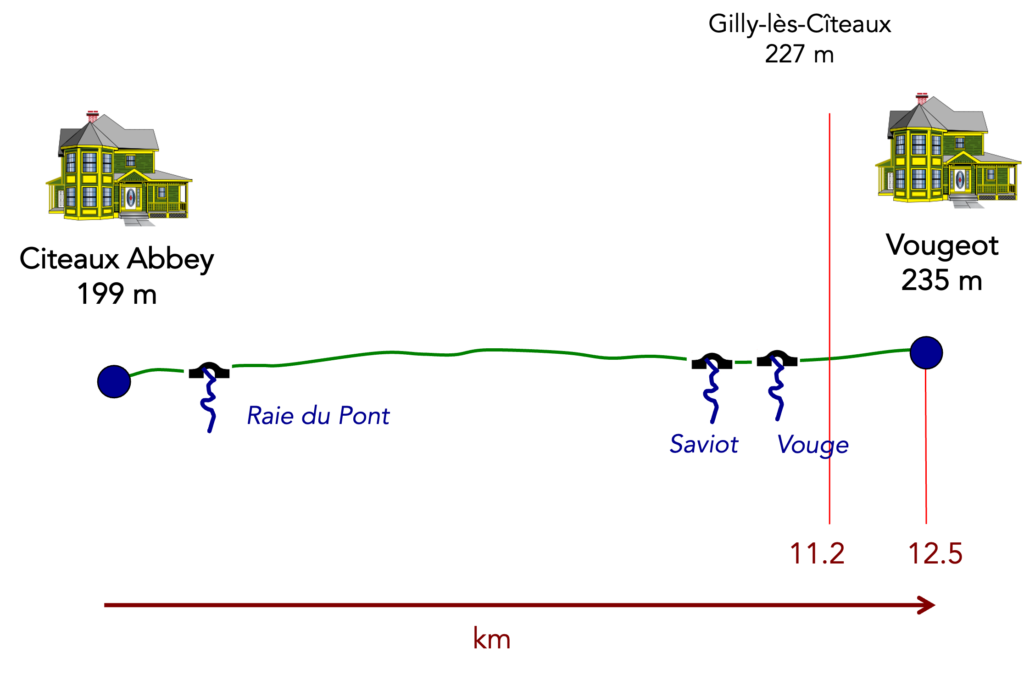

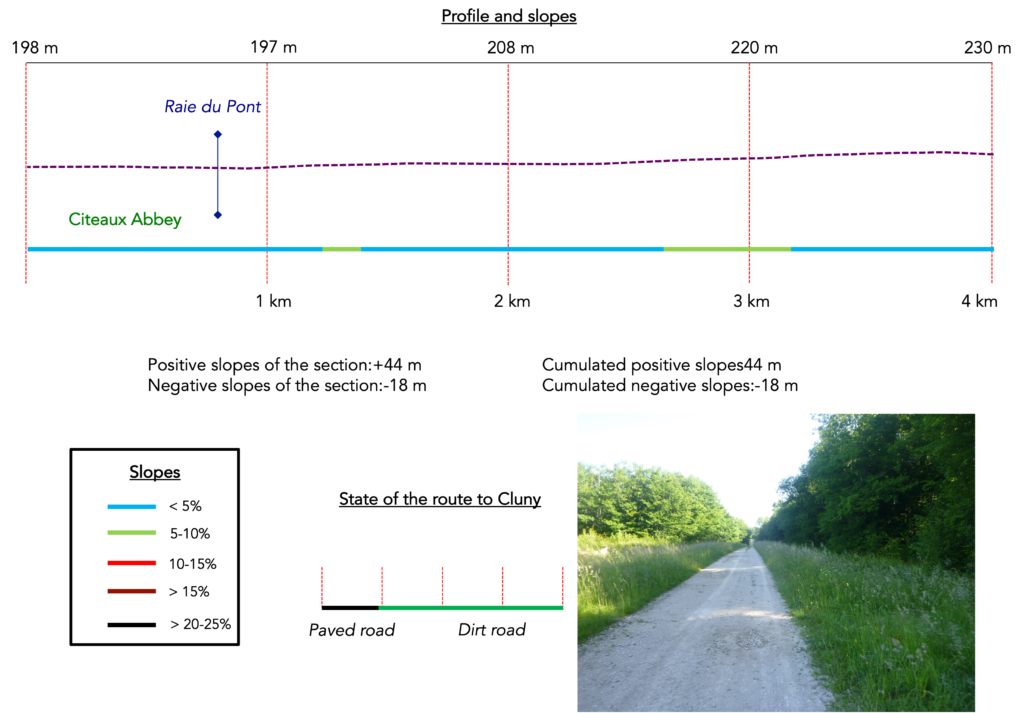

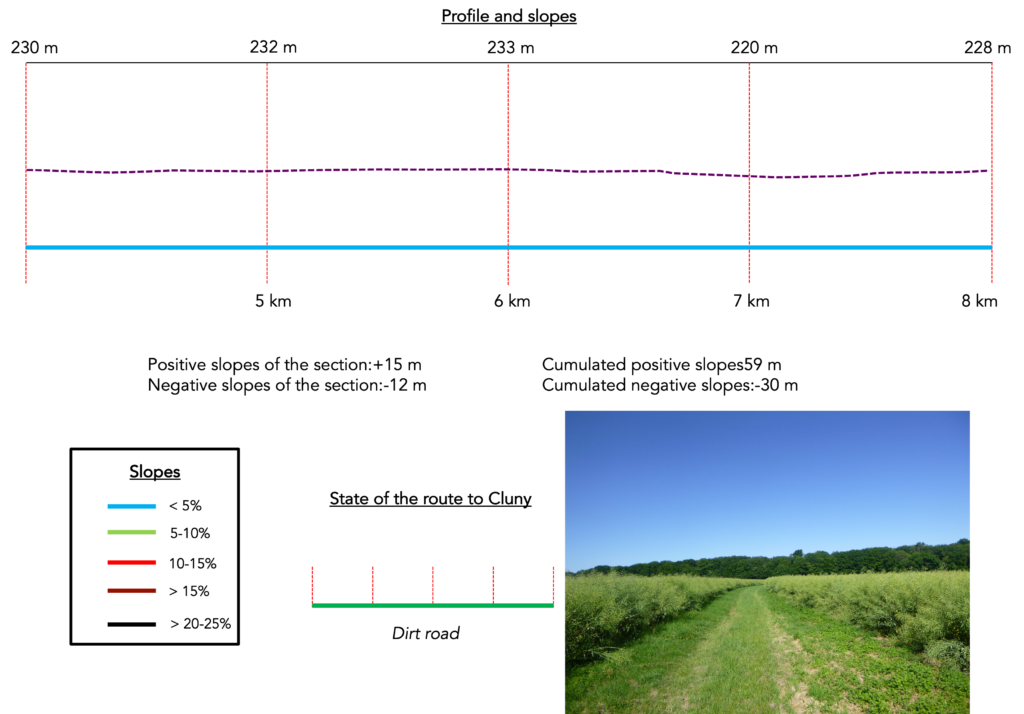

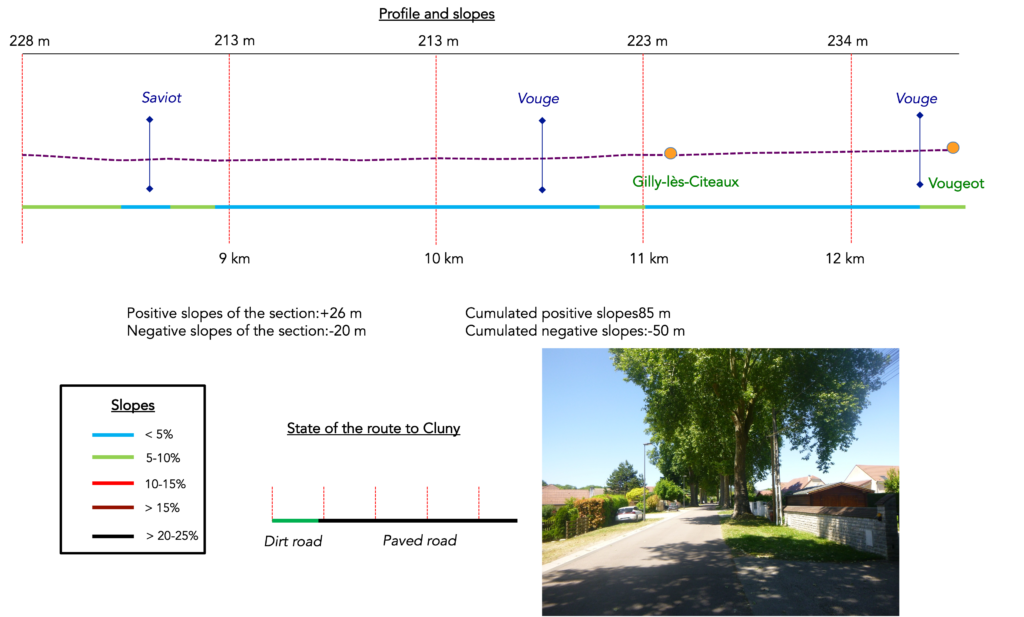

Difficulty level: Today’s route is almost flat, with no difficulty at all (+85 meters / −50 meters).

State of the route: Today, paths take precedence over roads:

- Paved roads: 4.2 km

- Dirt roads: 8.3 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

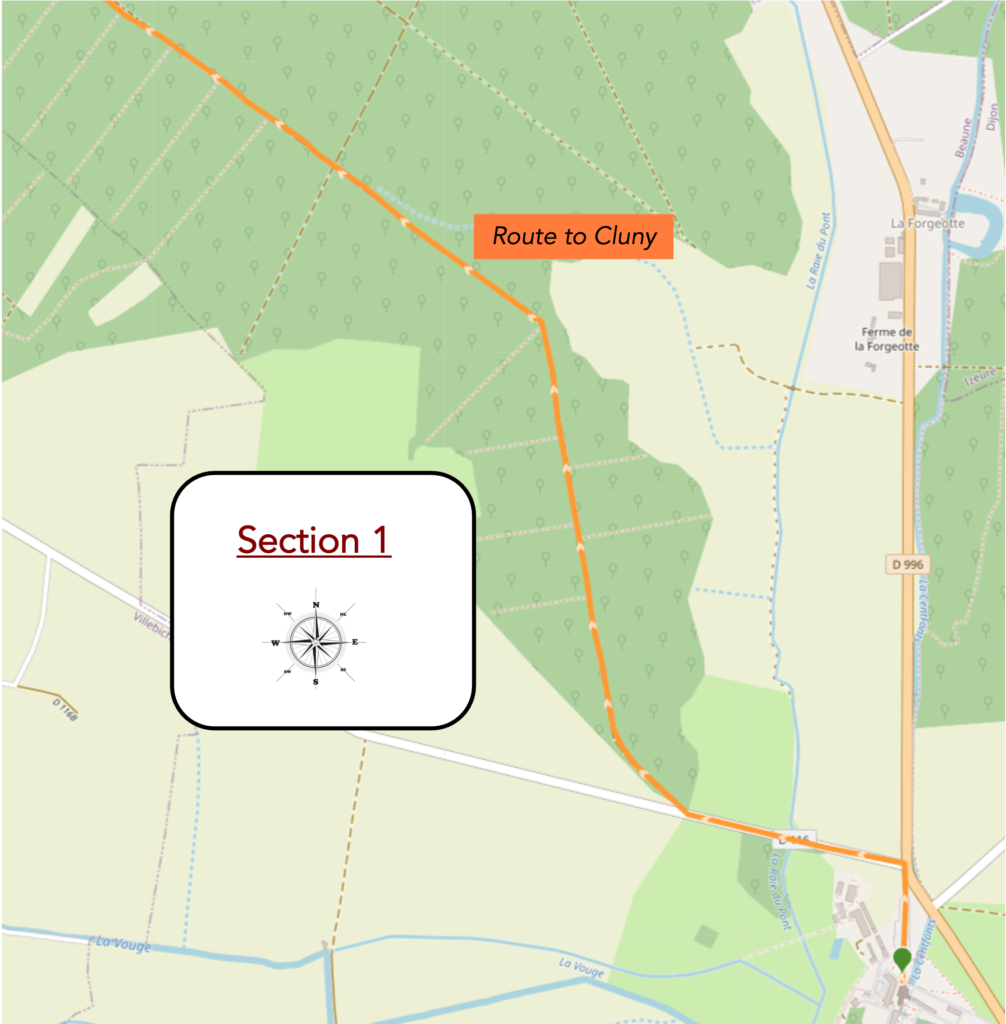

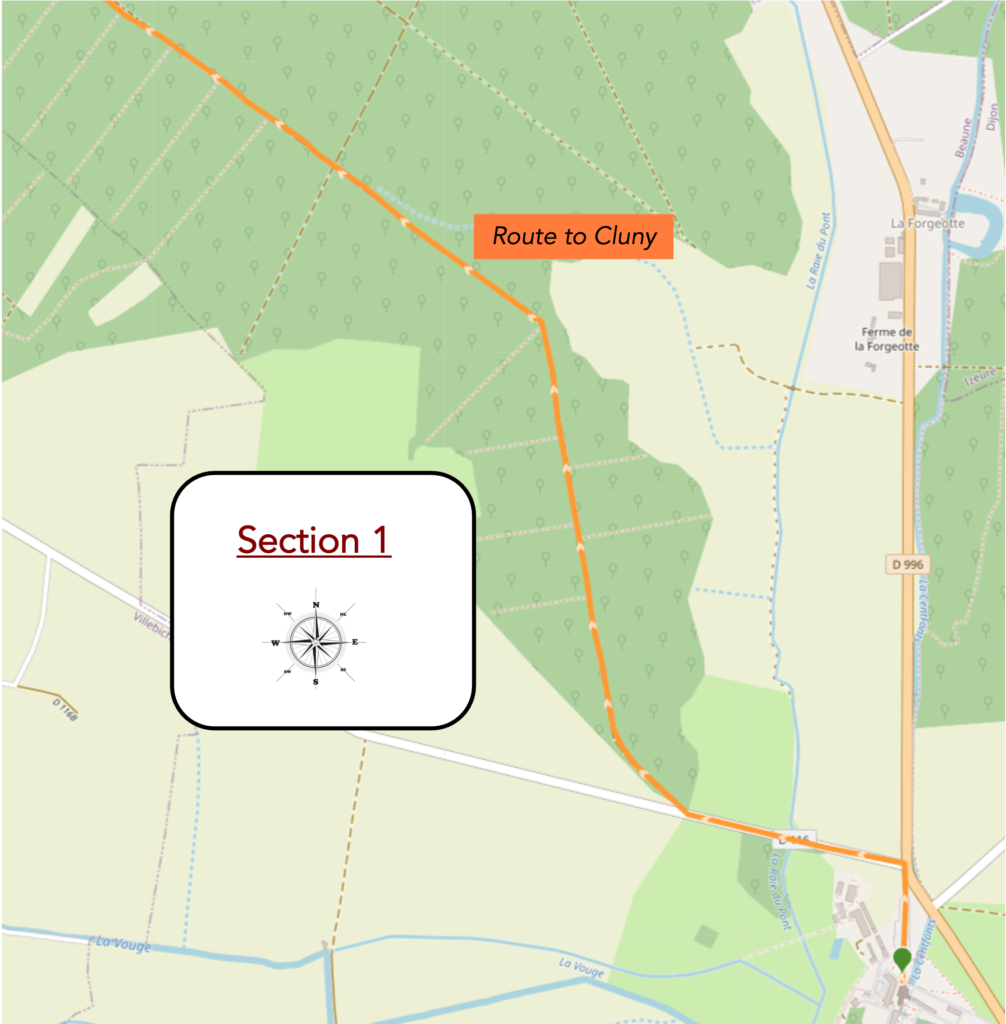

Section 1: In the great forest of Cîteaux

Overview of the route’s challenges: route with no difficulty at all.

| The journey opens on a solemn note. It is from the church of Cîteaux, the beating heart of the ancient abbey, that you pass through the great gate, the very one that borders the parking area, as if the present were gently yielding to the past. This is where your route begins. |

|

|

| At the crossroads, the route does not hesitate and resolutely chooses the road toward Villebichot. This is no ordinary intersection. It is a bifurcation of reality itself, a discreet nod to the walker who knows how to read between the lines. |

|

|

| Under a vast and silent sky, the road runs straight ahead, its clear line cutting through the countryside like a precise incision. |

|

|

| It sets off toward the forest, like an outstretched arm reaching for mystery. |

|

|

| Here comes a pivotal moment, one of those instants that only the attentive traveler perceives. After one kilometer, a dissonance appears. The official maps of the Way of Compostela in Burgundy betray you here, leading straight onto asphalt. But a scallop shell, placed like a riddle, gently urges you to turn, to plunge into the shadow of the trees. A choice presents itself. The safety of the map, or the vibrant call of the shell toward the forest of Grange Neuve. |

|

|

| Do not be afraid if you follow the shell. You will not lose your way. The guide mentions a wooden marker, a timid sentinel of the Path of the Monks. We did not see it. Yet the path is there, obvious, broad, and pleasingly stony. It cuts through the forest like a white vein, straight and tireless, bordered by shadows and murmurs. |

|

|

| With every step, the same vegetal hosts greet you, sentinels standing within a dense silence. Beeches and hornbeams, tall and supple, sway at the slightest breath. Ash trees, vast and generous, spread their arms like parasols. Maples, frail yet stubborn, punctuate the path, while oaks, shaggy and thick, impose themselves like slightly mad old sages. There are few chestnut trees or conifers here. This is a deciduous forest, a bright sanctuary. |

|

|

| At times, the ground grows gentler, the stones fade, and a clearing opens, a fragile breath in the midst of this relentless advance. But the path, insatiable, immediately resumes its course. |

|

|

| It does not bow or bend. It runs on, straight as a promise. |

|

|

| Beyond the path, a clearing sometimes opens, hinting at a wild and untamed nature. |

|

|

| And the dirt road stretches on, insatiable, along hedges of deciduous trees. |

|

|

| Along the path stands a new type of oak. To the eye, it seems little different from its fellows. |

|

|

| And suddenly, almost imperceptibly, something new appears. The path sketches a bend. It is a shiver within monotony, a curve like a wink. Something might happen. |

|

|

| The forest then opens in a grand gesture, just for a moment. A small clearing bathed in light reveals deciduous trees rising high, so high they seem to reach for the clouds. Nature here becomes a cathedral. |

|

|

| But this respite lasts only a heartbeat. The wide path resumes its obstinate progress. Straight and implacable, the line extends like a taut thread toward the invisible. |

|

|

| You can almost sense the murmur of silence itself, like an invitation to surrender. |

|

|

| Further on, the path crosses a discreet dirt track, worn by the patient back and forth of forestry workers. But here there is no ambiguity. A scallop shell, struck through with a firm line, forbids this detour. Immediate relief. Even in the heart of these deep woods, a marker keeps watch. The pilgrim is not abandoned. He continues to follow the sacred vein of the Way of Compostela. |

|

|

| In this age-old silence, it sometimes happens that a silhouette appears. A jogger, alone and focused, like a fleeting human breath within this green cathedral. They are rare, yet more frequent than walkers. Their stride cuts the air but does not disturb the peace of the place. |

|

|

| And the dirt road continues, relentless. Straight as an oath, it stretches endlessly, monotonous, devoid of detours and incidents alike, stubborn in its advance. It is a line drawn between two silences. |

|

|

| Soon, signs of human exploitation reappear. Loggers have left their mark. More open areas appear, along which trees, packed like sardines in a tin, bear witness to an order imposed upon nature. An industrial rhythm slips in here, discreet yet perceptible. |

|

|

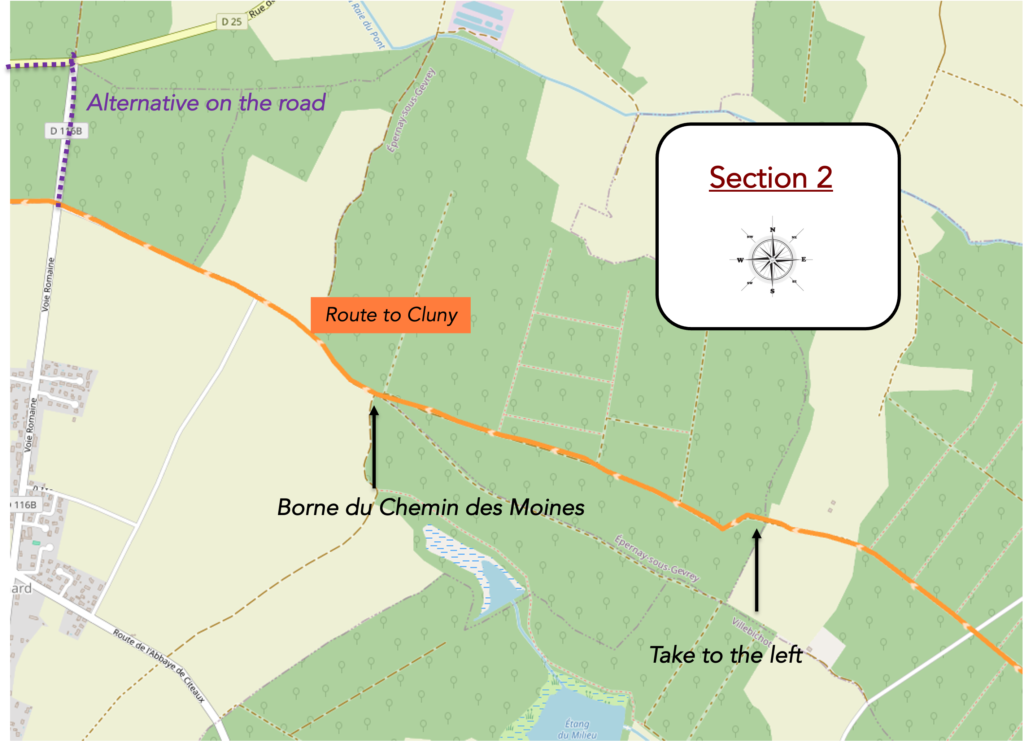

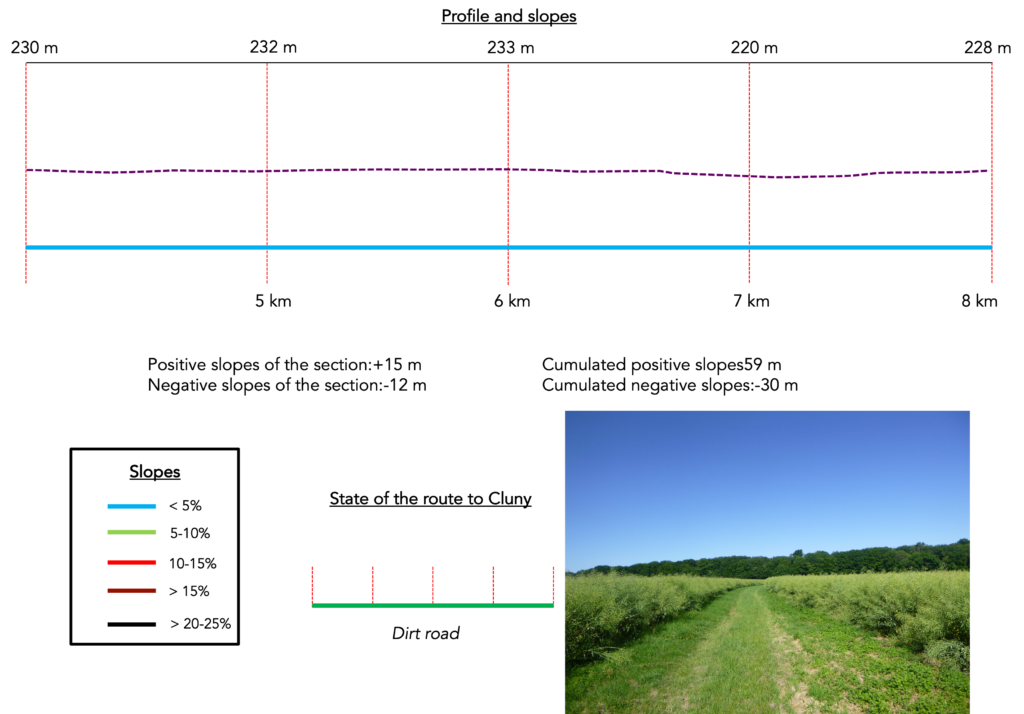

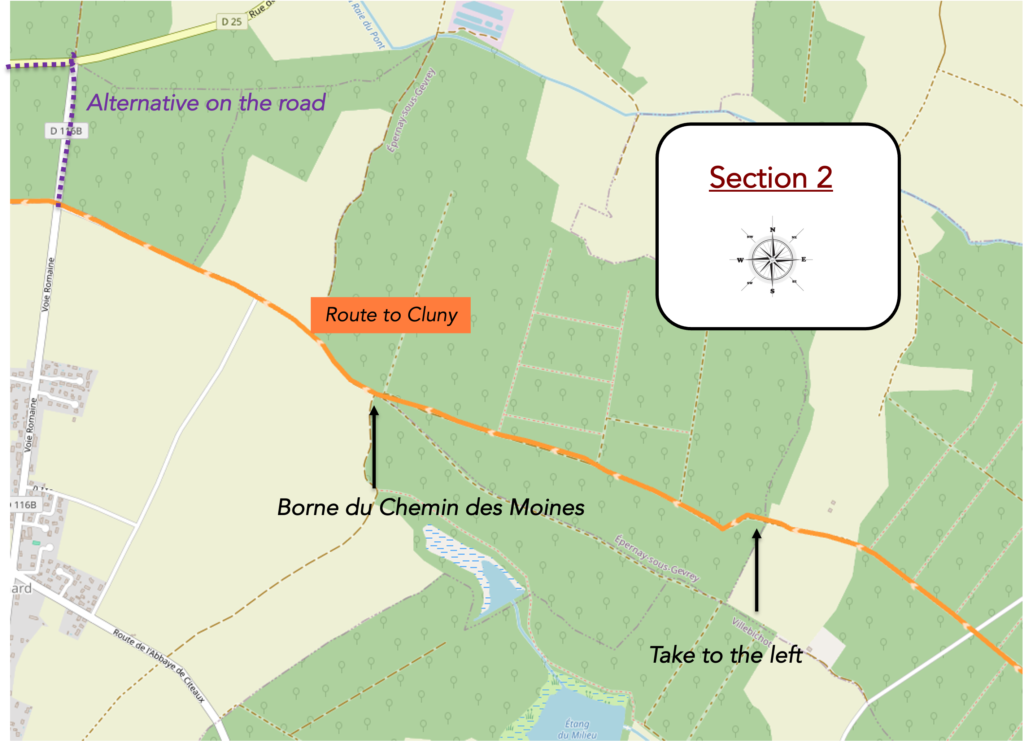

Section 2: In the forest as Gilly-lès- Cîteaux approaches

Overview of the route’s challenges: route with no difficulty at all.

| At last, after three long kilometers of forest immersion, a small asphalt road rises before you, like a modern temptation, an easy escape toward the civilized world. An awkward red arrow invites you to follow it. |

|

|

And like a benevolent wink, another scallop shell, oriented without ambiguity, reminds you that your route does not falter. It continues straight ahead, with calm assurance. .

| The path continues its course through the heart of the woods, winding over packed earth that the heavy tires of forestry tractors have churned in places. The ground bears the scars, like a parchment scratched by impatient hands. . |

|

|

| A little further on, grass takes over. It gently invades the path, covering the earth with a soft, almost cushioned carpet, as if the forest wished to heal its own wounds. |

|

|

| Then, without warning, the path finally escapes the cover of the trees. It emerges into a vast and luminous clearing, a breath of air after the density of the forest. |

|

|

| Here today, it is a sea of oilseed crops that welcomes you. The path crosses an ocean of rapeseed, rippling in the breeze like a vegetal swell. Hundreds of hectares vibrate beneath the sun. Tomorrow, it might be wheat, sunflower, or fallow land. The earth changes its face according to the rhythm of seasons and people. |

|

|

| Then, like a heartbeat after this rural interlude, the path plunges back into the forest. |

|

|

| Beeches and hornbeams once again form their leafy arch, familiar and soothing. |

|

|

| A little further on, another clearing opens, peaceful and deserted. But here, there is no sign, no scallop shell, no whispered direction. Doubt settles in. Like an old hand, you pull out your compass, for the guide from the Friends of Compostela is of no help here. It is to the left that you sense the call of the route. Intuition or experience, it hardly matters. A choice must be made. We give you the answer. It is indeed to the left that you must go. |

|

|

| The path that opens before you is wide, packed earth, almost gentle beneath your steps. Few stones appear, and the forest is less dense, as if quietly withdrawing |

|

|

| The dirt road follows this tamed woodland for nearly a kilometer. Nothing seems to indicate that you are still on the correct route. |

|

|

| Once again, you may feel lost in this wild world. |

|

|

| And suddenly, like a deep breath, the forest recedes. Before you, the plain opens, bare and vast, plowed fields stretching to the horizon. Small villages punctuate the line of earth, like calm islands at the edge of the world. |

|

|

But this calm is deceptive. You have just entered a real trap. You search, you inspect, you scrutinize every stump and every post. No scallop shell. Nothing. Only a marker, that of the Path of the Monks, mentioned by the guide from the very start. It is indeed there, but it points in the wrong direction. For here, another itinerary, the Monks’ circuit, comes to blur the traces. So, you once again take out your compass, or your capricious GPS pointing toward Gilly, to the right. You then understand. In this rural labyrinth, without a reliable guide and without clear waymarking, intuition is required, or an invisible traveling companion. Neither the small guide from the Friends of Compostela nor the European maps offer a tangible truth here. It is indeed to the right that you must follow the packed earth road.

| The wide dirt road then inclines with an almost imperceptible docility. It descends gently, following the forest edge like a ribbon sliding along a cloak. To the left, fields stretch endlessly, vast and silent, bathed in light. |

|

|

| The track then frees itself from the forest. It undulates slowly through open land, without trees and without the slightest patch of shade. The sun reigns here as an absolute master over meadows and fields. The eye loses itself on the horizon, in the peaceful nakedness of the landscape. |

|

|

| It eventually crosses a small agricultural road, discreet and worn, and approaches a new grove that rises like a promise of shade in this sea of fields. |

|

|

| The path then follows the woodland patiently and at length, as if courting it. As far as the eye can see, fields unfold their undulating monotony, and the path, unperturbed, traces its line between nature and cultivation. |

|

|

| Little by little, earth gives way to asphalt in this uniform and monotonous agricultural landscape. |

|

|

|

|

| The road then joins the D116b, a narrow and quiet road leading to the village of Saint Bernard. Asphalt brings back a hint of civilization, yet uncertainty does not fade.

And once again, doubt returns. The guide warns you, “Take the road to the right. After a few meters, take the small trail on the left that runs along the forest. Follow it to emerge further on onto the departmental road D25.” Yes, a scallop shell, discreet and almost swallowed by tall grass, indicates that you should follow the road to the right. But there is no clear trace of a trail. And yet, there is indeed a path running along the forest edge, poorly defined in the tall grass and uninviting. Uncertainty thickens here like a fog. This approximate waymarking, throughout the region, sometimes borders on the absurd, all the more so as a red painted directional sign encourages you to take the road. So, with a touch of resignation, choose wisdom. Simply follow the road to the right. In the end, whichever option you take, both lead to the D25 on the road to Gilly. |

|

|

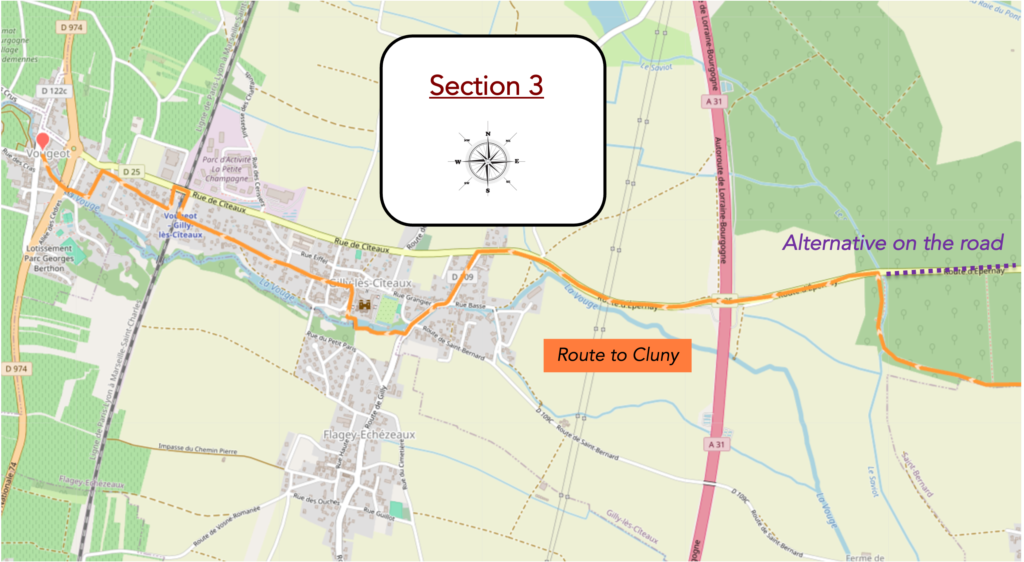

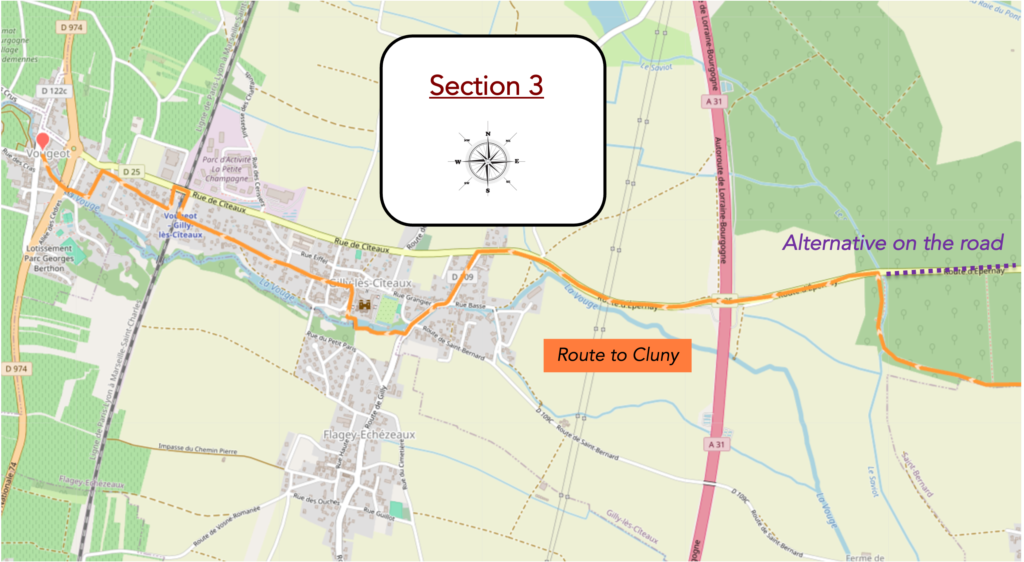

Section 3: Approaching the Vougeot vineyard

Overview of the route’s challenges: route with no difficulty at all.

| If you follow the road, your steps will inevitably lead you to the junction with the departmental road D25, that ribbon of asphalt where so many anonymous destinies converge. At the end of the road, turn left toward Gilly. . |

|

|

| Naturally, the long-awaited scallop shell is conspicuously absent here, as if the route had slipped from sight, like a fragile thread lost in the weave of the landscape. Perhaps one should have followed that hypothetical route, poorly marked and almost ghostlike, neglected by the clumsy hand of men. No matter. Turn left onto the road and let yourself be guided toward Gilly- lès- Cîteaux, where the bell towers seem to watch over travelers. |

|

|

| From there, the road unfolds with a stubborn, straight momentum, plunging into a dense forest where light grows scarce. The shadow of the trees closes around you like a dark cloak. |

|

|

Further on, a scallop shell finally reappears, a fragile stone marker gleaming at the roadside, reminding you that the authentic route did indeed pass through the discreet path. Reassured, the pilgrim understands that he did not wander in vain. This detour, chosen for safety, was not a betrayal but a variant offered to those who hesitate.

| At the edge of this deep woodland, the road comes to follow a modest stream, the Saviot, winding quietly through tall grasses. One might almost overlook it, so discreet is its presence, yet its gentle murmur is enough to recall that water, sometimes unseen, remains the secret soul of landscapes. |

|

|

| The road then opens wide onto the plain. It cuts through vast fields stretching as far as the eye can see, true expanses of gold or green depending on the season, where human labor converses patiently with the land. |

|

|

| Soon after comes the overwhelming shadow of the A31 motorway, that river of steel and asphalt known as the Lorraine Burgundy motorway. It links Luxembourg to Beaune, ceaselessly carrying the flow of heavy trucks from Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands, crossing Europe like tireless ants. It passes through Metz, Nancy, Dijon, anonymous halts along this great modern route. |

|

|

What surprise, then, to find a scallop shell engraved on the bridge, beautiful, clear, almost insolent in its clarity, yet entirely useless here. For no sensible pilgrim would venture into the entrails of a motorway, a realm of noise and danger.

| The departmental road D25 continues calmly between the fields. Already the first signs announcing the Clos de Vougeot come into view. That name alone resonates like a promise of happiness for informed wine lovers, for it embodies excellence and the age-old genius of winemakers. |

|

|

| A little further on, the guide whispers, “Before the high voltage lines, take the grassy trail that follows the Vouge upstream.” On the roadside, there is indeed an opening, half trail, half illusion, seemingly inviting adventure. But at this stage of the route, after so many traps and false starts, and since no scallop shell confirms it, wisdom suggests renouncing this uncertain escape. The road, faithful, leads straight toward Gilly, already visible on the horizon like a long-awaited haven. |

|

|

| At last, your steps carry you into Gilly- lès- Cîteaux. The village, with its eight hundred inhabitants, appears as a blessed stop. |

|

|

| At the entrance, a handsome hotel opens its doors to pilgrims, especially those who did not stop earlier at the Abbey of Cîteaux. The route now follows the Route des Graviers, an invitation to drift gently toward the Vouge, that capricious and complex river with changing moods, which crosses and shapes the land. |

|

|

| After crossing the Vouge by a modest bridge, the route briefly follows the Route de Flagey. Though short, this passage gives the traveler the sense of moving ever closer to the historical and spiritual heart of the region. The road becomes a transition, a passage, almost a rite, before sinking into the memory of the place. |

|

|

| A scallop shell, well placed this time, like a benevolent star, invites you to leave the monotonous asphalt. It shines like a promise, recalling that the Way of Saint James is never walked in the banality of straight roads, but in detours, in deviations, where true encounters with the landscape begin. |

|

|

| A grassy trail then opens, running along the woodland of the castle. Bordered by an old moss covered wall, it follows the murmur of the stream on your right. |

|

|

| At the exit of the woodland, the entire place breathes an absolute charm, around the small footbridges that cross the stream. |

|

|

| Between the Seigneur’s house and the former presbytery, now restored, a discreet passage leads to one of the two nineteenth century washhouses. Hidden from view, equipped with stone slabs to ease the work of washerwomen, it stands near a slender footbridge arching gracefully over the Vouge. Here, one can still sense the daily gestures of another age. |

|

|

Gilly, though now reduced to the scale of a modest village, was in the Middle Ages a center of unsuspected influence. As early as the sixth century, a Benedictine priory was established here, laying the spiritual foundations that would shape the site’s history. At the end of the twelfth century, the estate passed into the hands of the Abbey of Cîteaux. Masters in taming water, the monks developed the Vouge flowing through the park, creating irrigation systems and fish farming. The castle, former residence of the abbots of Cîteaux, then rose, a fifteenth and seventeenth century building with a turbulent life. Built on the site of an earlier priory once entrusted to the Cistercians by the monks of Saint Germain des Prés, it soon acquired fortifications to withstand the threats of the Hundred Years’ War. Time spared nothing. Plundered and destroyed during the Wars of Religion, it became national property during the Revolution and was sold in 1791 to a Parisian timber merchant. It then passed from hand to hand, reduced to a simple agricultural holding.

The twentieth century nevertheless saved it from oblivion. Acquired in 1977 by the Côte d’Or General Council, it briefly housed the Grenier de Bourgogne theatre before being reborn in 1988 as a luxury hotel. Its ancient stones still shelter treasures. The massive and intact thirteenth century kitchen remains, as does a superb rib vaulted cellar where monks once stored their barrels. The castle is finally surrounded by a park with formal French gardens, ordered and refined, recalling the grandeur of its past.

You must cross the castle moats, spanned by a footbridge, to reach the Cistercian church of Saint Germain, built in the fourteenth century and modified in the sixteenth. After the Revolution, it became the parish church, now serving the villagers. A hidden door set into the stone once allowed abbots to pass directly from the castle to the church, a secret passage bearing witness to the intimate bond between spiritual and temporal power. In the seventeenth century, the abbots of Cîteaux rebuilt, on ancient remains, a prestigious residence, restoring moats and drawbridges to the ramparts. |

|

|

|

|

| The route gradually moves away from the castle, crossing its enclosure to enter Rue des Abreuvoirs. Soon it reaches Avenue du Recteur Marcel Bouchard, where the town hall stands, a modern symbol of collective organization, facing the age-old witnesses of monks and lords. The route then follows the winding streets of the village. |

|

|

| It opens onto a long avenue stretching majestically beneath a vault of trees. Like an avenue of honor, it runs straight and implacable toward the Vougeot railway station. |

|

|

| At the very end of the avenue, near a parking area, the route suddenly changes direction. At a right angle, it turns toward the station, a place of departure and arrival, a crossroads where pilgrims and ordinary travelers meet. |

|

|

| Here, Gilly and Vougeot merge without visible boundary. Like twin sisters with distinct yet inseparable characters, they share this same station, a discreet witness to their common destiny. The route, too, ignores any separation, gliding naturally from one village to the other, as if the whole territory were a single breath. Two symmetrical stairways allow the railway line to be crossed and the station reached from either side. |

|

|

| You are now in the outskirts of Vougeot. The route then continues along Rue de la Gare, lined with neat villas. The alignment of these homes, with their carefully tended gardens, contrasts with the wild forests and vineyards crossed earlier. At the far end, the road turns left onto the Chemin du Closeau, modest and discreet. |

|

|

| The route then becomes winding, following the contours of the land as if testing the walker’s patience. This undulation leads, a little further on, back to the Vouge, faithful companion of the route, returning like a friend never truly absent. |

|

|

| Through a graceful play of small bridges, the route once again crosses the river. Here, the Vouge unfolds freely, tracing wide meanders through an intact nature, barely disturbed by the distant murmur of roads. One might think the water, in its capricious curves, seeks to hold the traveler back, to slow his step and remind him of the beauty of the moment. |

|

|

| On the opposite bank, an old washhouse still rests, a solid witness to the daily life of generations past. These washhouses, modest yet essential, form the living heritage of the entire region. Their presence punctuates the route like a breath, reminding us that even the humblest history deserves memory and respect. |

|

|

| Rue du Moulin advances gently toward the heart of Vougeot, faithfully following the Vouge whose murmur accompanies the traveler’s steps. Here stand magnificent winegrowers’ houses built of pale stone, softened by centuries and by the Burgundian sun. Their vaulted cellars, sometimes still in use, remind us that wine is not merely a product of the land, but an art of living inscribed in the very stones of these homes. |

|

|

| The street soon opens onto the village center, near the splendid Clos de la Vouge. This hotel of discreet refinement quite literally dips its feet into the stream that encircles it with fresh, clear water. The setting feels almost unreal. Between living water and ancient stone, the walker rediscovers the subtle harmony of a place that knows how to unite elegance and authenticity. |

|

|

|

|

| Vougeot, a small tourist and wine village of only one hundred and fifty inhabitants, nevertheless radiates across the world. Situated on the mythical Route des Grands Crus, between Chambolle Musigny and the Côte de Nuits, it embodies the prestige of Burgundy. Its renown rests above all on the famous grand cru of the Clos de Vougeot, but other premier cru appellations add their voices to this chorus of nobility: Clos de la Perrière, Clos Blanc, Les Crâs, and the Petits Vougeots. Names that resonate like promises of refined pleasure, to be savored slowly, provided one’s finances allow it. To this wine wealth is added a rich culinary folklore. The Château du Clos de Vougeot, a true sanctuary of wine, and its Confrérie des Chevaliers du Tastevin, whose lavish banquets celebrate with flair the gastronomic art of Burgundy. Here, vine and table meet in an eternal alliance, and every stone seems steeped in this culture of sharing and celebration. |

|

|

| From the vibrant heart of Vougeot, your next stop can be none other than the Château du Clos de Vougeot, this sanctuary of stone and vine, nestled only a few steps away. Set amid the rows of vines, surrounded by grands crus like a court of honor, the Clos de Vougeot reveals itself in all its solitary majesty. It is a castle that seems to have grown directly from the soil, as if the stones had crystallized from the vine itself. |

|

|

| The Château du Clos de Vougeot was built between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, in a Cistercian sobriety later enriched with delicate Renaissance touches. Everything begins in 1098, when monks seeking rigor founded the Abbey of Cîteaux, twelve kilometers southeast of Vougeot. These Cistercians, spiritual rivals of the opulent Cluniacs, chose to cultivate the vine with a fervor and knowledge that would become legendary. Between 1109 and 1115, through successive donations and acquisitions, they assembled the lands that would form the famous clos, soon enclosed by walls to protect its purity. For nearly seven centuries, these men in white habits planted, pruned, and cared for the vines, developing a vineyard that would bring glory to an entire region. Long before their labor, however, the Romans had already recognized the genius of the Burgundian slopes, where pinot thrived. The legions, more generous than innovative, brought not this already native grape, but gouais, a white variety whose harsh and rustic wine sustained generations of peasants. In the plains, this variety proliferated, offering a popular drink, while on the slopes, pinot noir had long produced wines of excellence. An astonishing fact emerges. When left to its own devices, the vine hybridizes spontaneously, as if the earth itself were seeking new harmonies. From these chance unions arose a profusion of varieties, from which most European grape varieties descend, born of an original union between pinot noir and gouais. Over time, humans domesticated these crossings, fixing varieties and disciplining them into clones. Yet within each vine still sleeps the adventure of ancient crossings. In the sixteenth century, a new breath enriched the estate. The forty eighth abbot of Cîteaux added to the utilitarian buildings an elegant Renaissance residence inspired by the Louvre, in which he could reside. Thus was born the Château du Clos de Vougeot in the form we know today. The French Revolution nearly swept everything away. The Abbey of Cîteaux and its thirteen thousand hectares were confiscated as national property, and the Clos risked falling into oblivion. But destiny decided otherwise. Thanks to the banker Gabriel Julien Ouvrard and later the visionary wine merchant Léonce Bocquet, the castle was saved from inevitable decline. Bocquet, deeply attached to the site, invested his fortune and ultimately came to rest within the monument’s walls in 1913. After complex inheritances, Étienne Camuzet, a deputy and winegrower from Vosne Romanée, repurchased the estate in 1920. Fifteen hectares of vines were then distributed among about fifteen local owners. Unable to maintain the castle, he sold it in 1944 to the Société Civile des Amis du Château du Clos de Vougeot, which bound the monument’s destiny to that of the Confrérie des Chevaliers du Tastevin, founded ten years earlier. During the second half of the twentieth century, its members undertook extensive restoration work. |

|

|

| The cultivation of the vine soon imposed upon the monks a learned organization, and with it the need to erect buildings commensurate with their work. In the fifteenth century, they built a vat house shaped like a cloister, a place both spiritual and practical, where architecture seemed to converse with the vine. Four monumental oak presses stood there like mechanical cathedrals. Each could press four tons of grapes, releasing with solemn creaks the precious juice of the harvest. Around them, countless vats received the newborn wine, like cradles sheltering a still fragile youth. Soon after, the monks built a vast cellar, half buried in the earth, whose eight stone pillars supported an immense wooden framework. Through discreet windows, light entered sparingly, taming air and temperature to preserve the sacred balance of the wine in its making. This cellar could hold up to two thousand barrels, those 228 liter casks that made the vineyard’s heart beat. Above this subterranean lair, the monks arranged a vast attic whose monumental frame was originally crowned with a roof of Burgundy stone. This immense and severe space served as a dormitory for brothers coming from the Abbey of Cîteaux to work the vines. There, the breath of men mingled with the sighs of wood. The frame, fashioned from chestnut, had the ingenious property of discouraging spiders from spinning their webs. A subtle stratagem that made this attic an austere yet preserved place of rest. |

|

|

|

|

| Much later, in 2015, Burgundy received a long-awaited consecration. UNESCO officially recognized its Climats, those vineyard parcels patiently shaped by centuries of human labor and the genius of terroir. After a decade of determined struggle, World Heritage listing was achieved, and the Clos de Vougeot became its natural seat. For Burgundians, no other place could so fully embody the soul of their vineyard. Above institutions and almost outside time, the castle stands upheld by the chivalric spirit of the Confrérie des Chevaliers du Tastevin, which has inducted more than twelve thousand members over the years to defend the image and glory of Burgundy wines across all continents.

Today, although the surrounding fifty hectares are divided among more than eighty owners, the Clos de Vougeot remains a beacon, a light shining far beyond its walls. Here, Burgundy wines and gastronomy are celebrated in solemn banquets, gatherings where splendor, tradition, and friendship intertwine. Even though the castle no longer produces wine itself, it remains the emblem of a millennium of history, the unshakable witness to the marriage between stone and vine, between the patient labor of humankind and the generosity of the earth. |

|

|

Official accommodations in Burgundy/Franche-Comté

- La Closerie de Gilly, 16 Avenue Bouchard, Gilly-lès-Citeaux; 03 80 60 87 74; Guestroom

- L’Orée des Vignes, 6 Route d’Epernay, Gilly-lès-Citeaux; 03 80 62 49 77; Hotel

- Hôtel-restaurant du Château de Gilly, Gilly-lès-Citeaux; 03 80 62 89 98; Hotel

- Hôtel de Vougeot, 18 Rue du Vieux Château, Vougeot; 03 80 62 01 15; Hotel

- Hôtel-restaurant Le Clos de la Vouge, Rue du Moulin, Vougeot; 03 80 62 89 65; Hotel

Jacquaire accommodations (see introduction)

Airbnb

- Gilly-lès-Citeaux (7)

- Vougeot (3)

Each year, the route changes. Some accommodations disappear; others appear. It is therefore impossible to create a definitive list. This list includes only lodgings located on the route itself or within one kilometer of it. For more detailed information, the guide Chemins de Compostelle en Rhône-Alpes, published by the Association of the Friends of Compostela, remains the reference. It also contains useful addresses for bars, restaurants, and bakeries along the way. On this stage, there should not be major difficulties finding a place to stay. It must be said: the region is not touristy. It offers other kinds of richness, but not abundant infrastructure. Today, Airbnb has become a new tourism reference that we cannot ignore. It has become the most important source of accommodations in all regions, even in those with limited tourist infrastructure. As you know, the addresses are not directly available. It is always strongly recommended to book in advance. Finding a bed at the last minute is sometimes a stroke of luck; better not rely on that every day. When making reservations, ask about available meals or breakfast options.

Feel free to leave comments. That is often how one climbs the Google rankings, and how more pilgrims will gain access to the site.

|

|

Next stage: Stage 15: Vougeot to Beaune |

|

|

Back ti menu |