Discovering a village of character

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

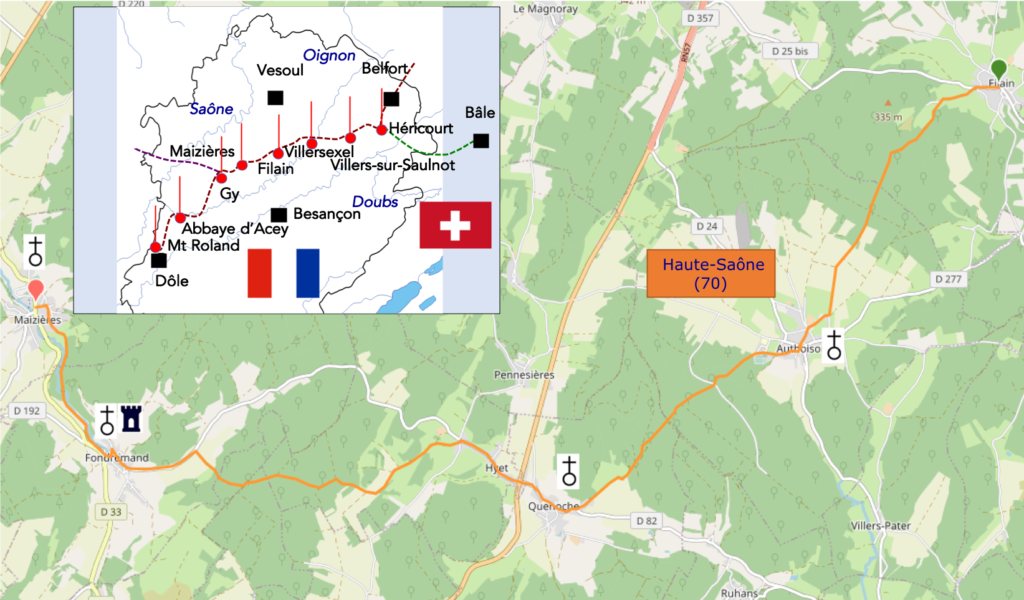

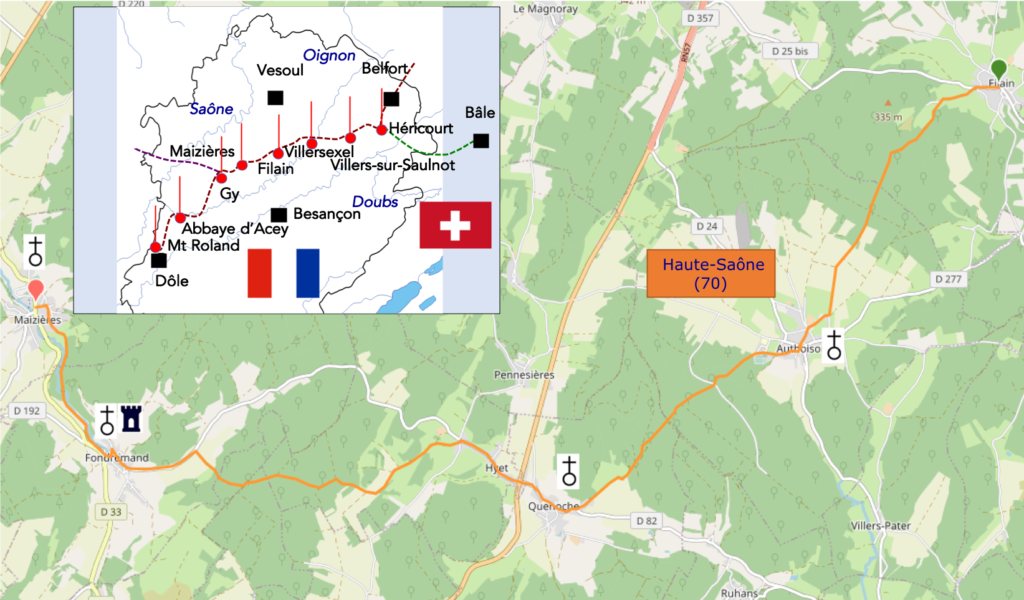

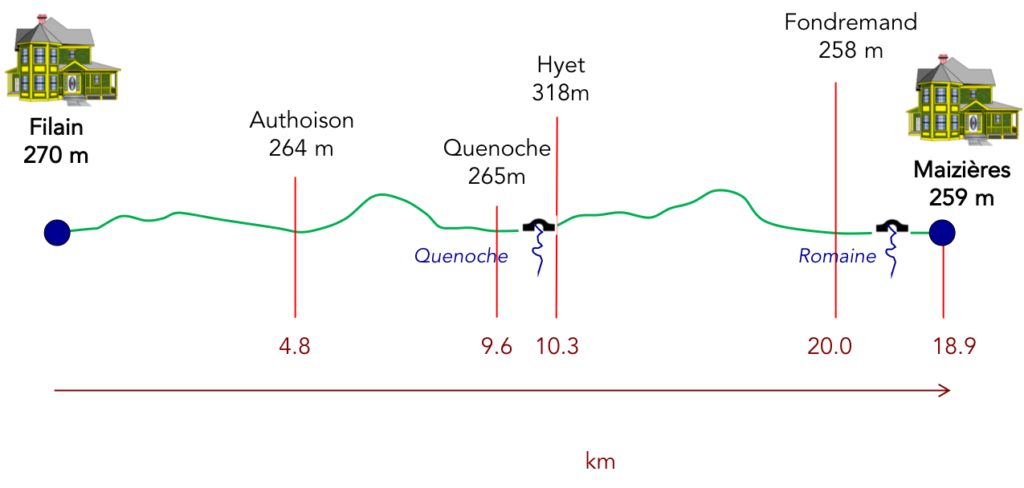

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-filain-a-maizieres-par-le-chemin-de-compostelle-80332522

| This is obviously not the case for all pilgrims, who may not feel comfortable reading GPS tracks and routes on a mobile phone, and there are still many places without an Internet connection. For this reason, you can find on Amazon a book that covers this route.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page. |

|

Haute-Saône is one of those regions where the landscape, though gentle and soothing, tends toward uniformity. The curves blend together, and the villages merge into the same palette of greens and pale stones. Yet one impression remains, persistent and almost physical: that of a land of great forests, vast, silent, and sovereign. Forests as beautiful as cathedrals, filled with straight beeches, ancient oaks, and dense foliage. You will also keep, strangely, the repeated image of the TGV, that steel arrow cutting across the landscape at great speed, never stopping here. It passes by, ghostly and distant, a cruel reminder that this land remains on the margins, ignored by fast routes, by those who travel without looking. It is a symbol of what this land is not: hurried, visible, connected. But there is one name, one place, that will escape oblivion: Fondremand. You will remember that name. It will shine somewhere in your memory, like a pebble polished by the stream of remembrance. For Fondremand is not like other villages. It is a discreet jewel, nestled in greenery, watched over by a fortress that still seems to guard its own walls. And above all, Fondremand is the cradle of a natural wonder: it is here that the Romaine springs forth, a clear, living source, almost sacred, that seems to be born from the rock to offer the world the water of memory.

How do pilgrims plan their route. Some imagine that it is enough to follow the signposting. But you will discover, to your cost, that the signposting is often inadequate. Others use guides available on the Internet, which are also often too basic. Others prefer GPS, provided they have imported the maps of the region onto their phones. Using this method, if you are an expert in GPS use, you will not get lost, even if the route proposed is sometimes not exactly the same as the one indicated by the shells. You will nevertheless arrive safely at the end of the stage. In this context, the site considered official is the European Route of the Ways of St. James of Compostela, https://camino-europe.eu/. For today’s stage, the map is accurate, but this is not always the case. With a GPS, it is even safer to use the Wikilocs maps that we make available, which describe the current marked route. However, not all pilgrims are experts in this type of walking, which to them distorts the spirit of the path. In that case, you can simply follow us and read along. Every difficult junction along the route has been indicated in order to prevent you from getting lost..

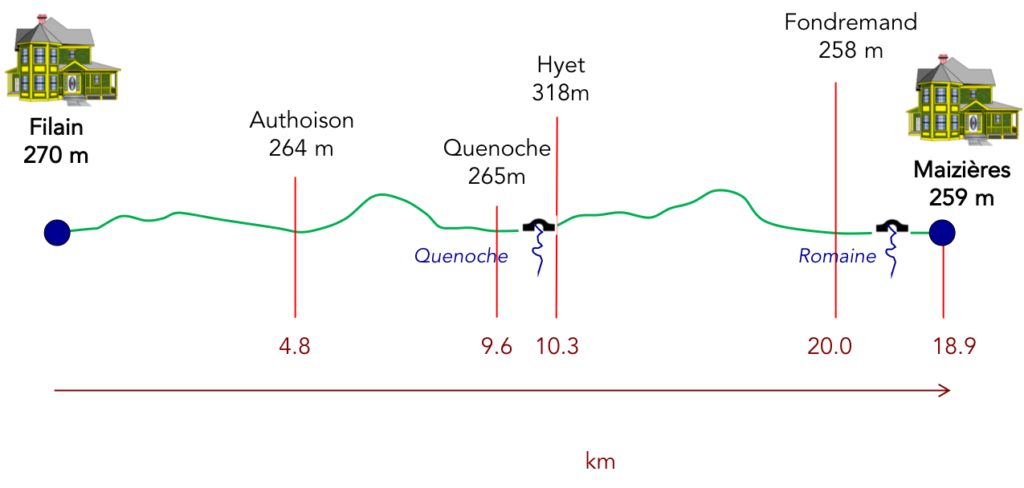

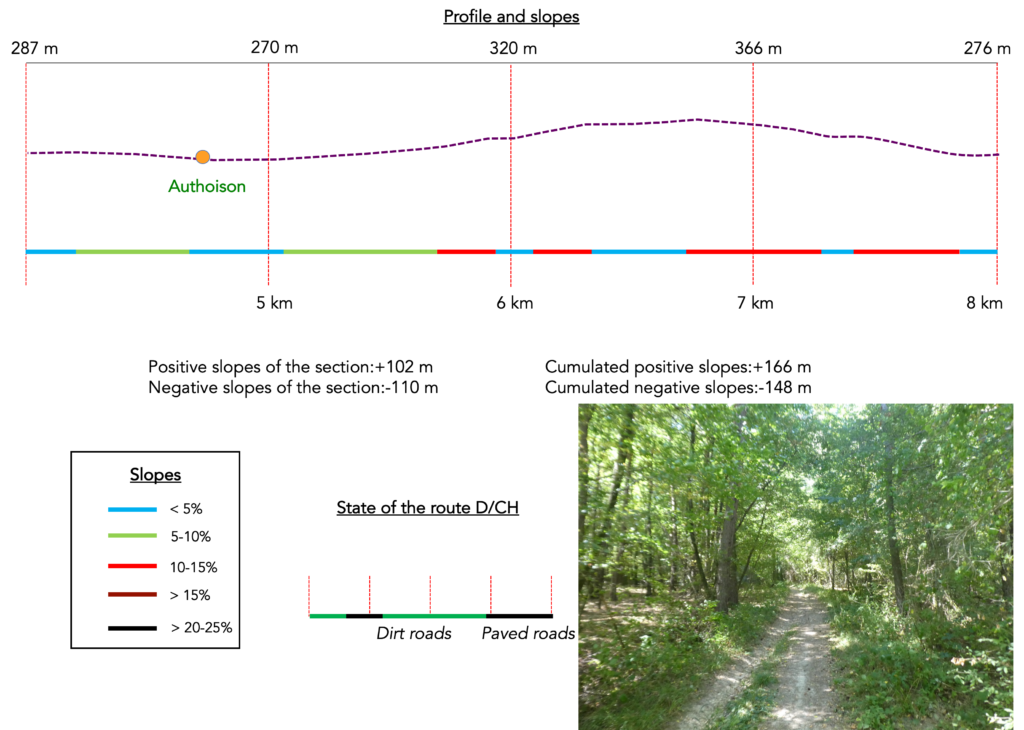

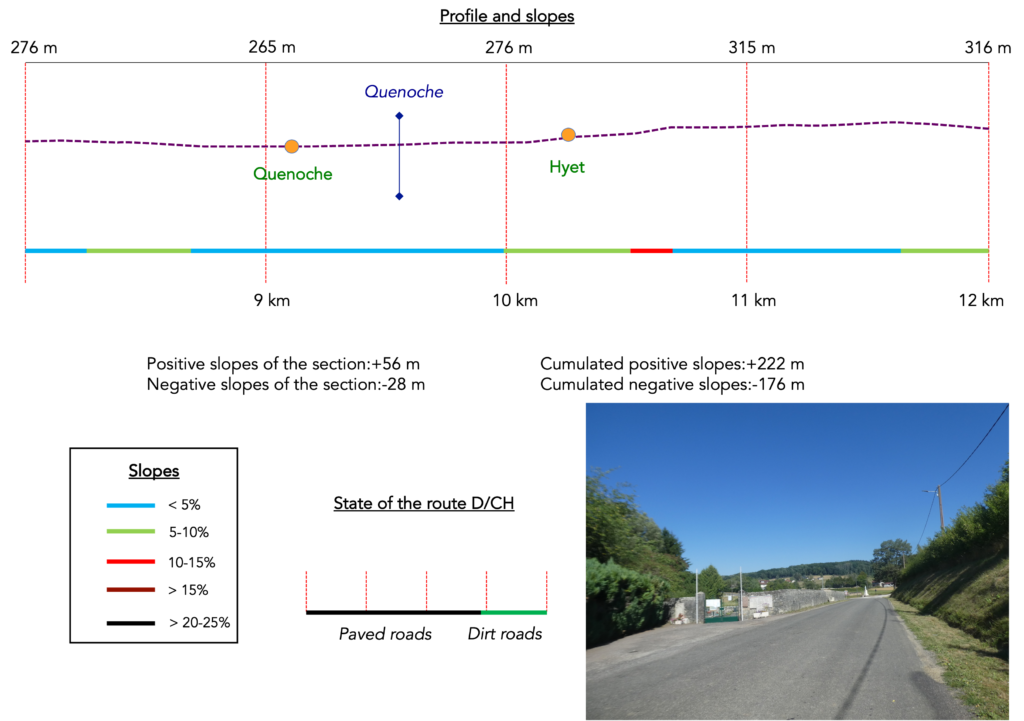

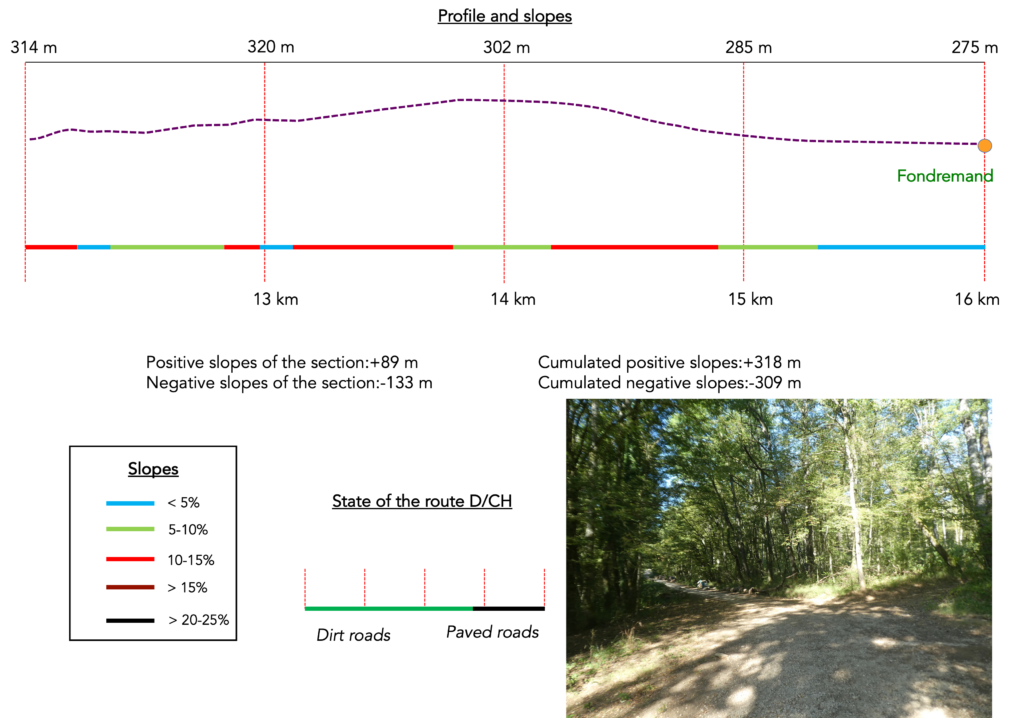

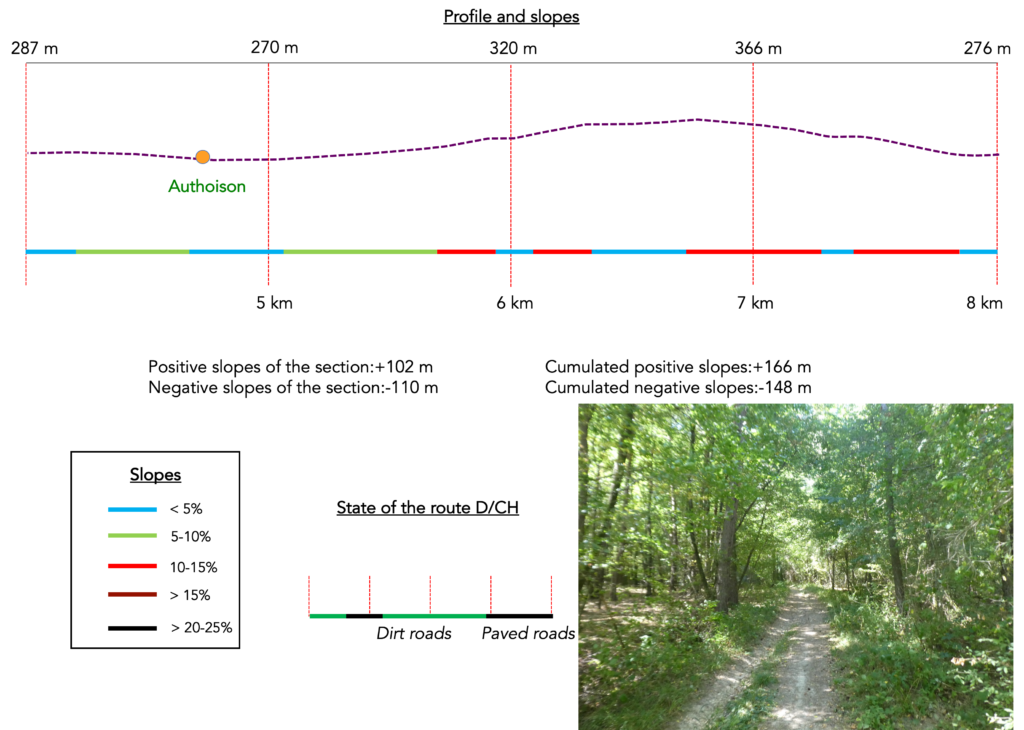

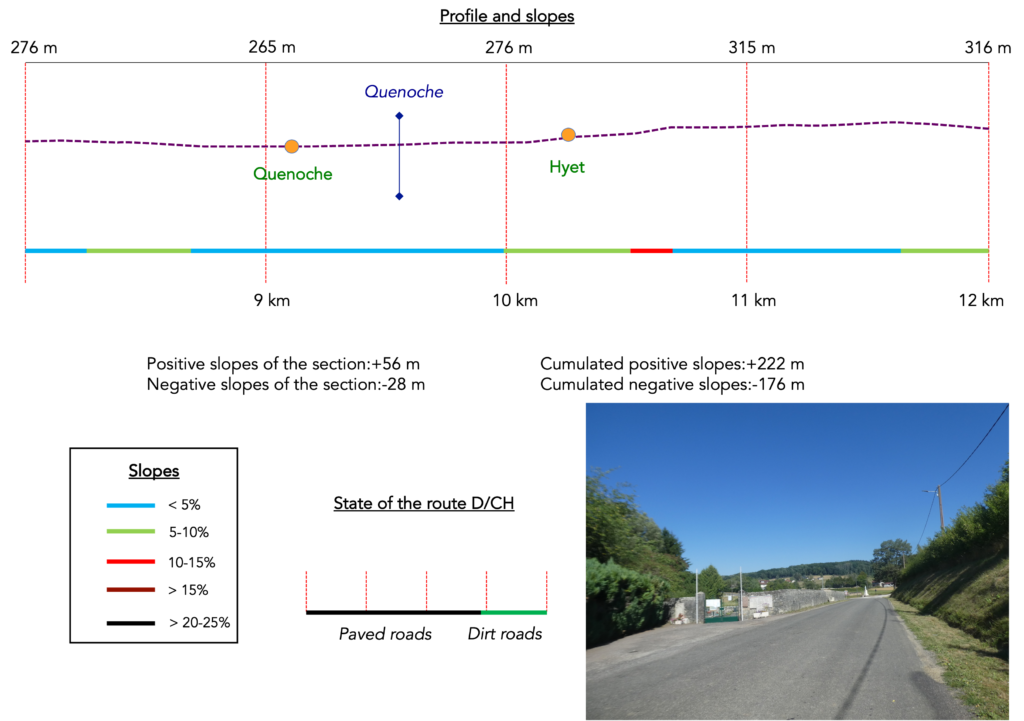

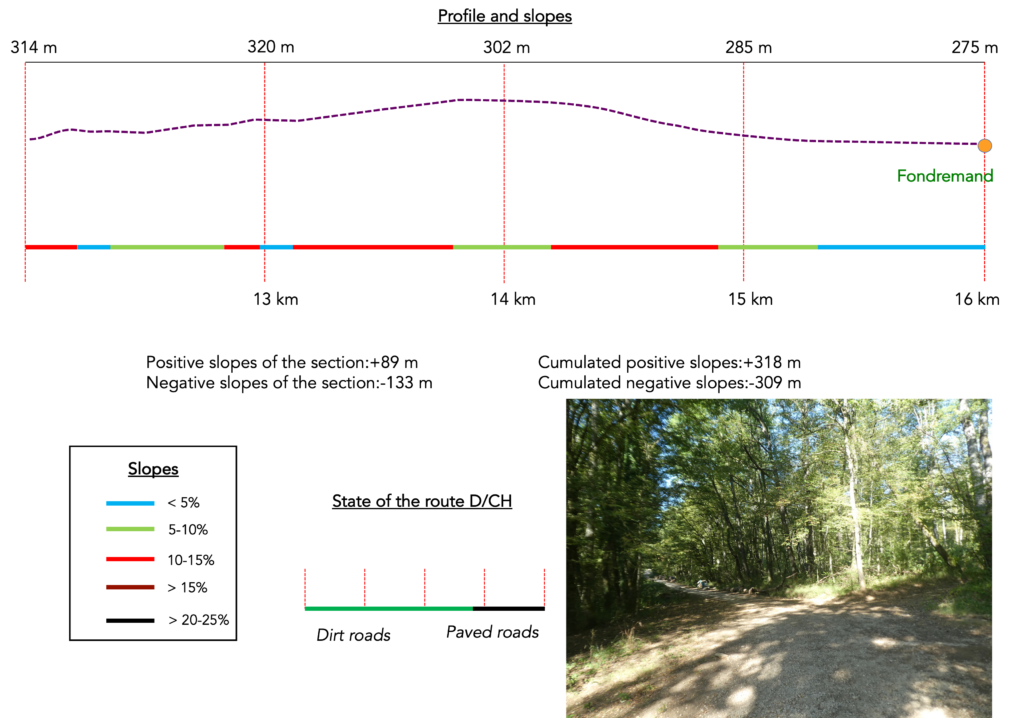

Difficulty level: The route today shows no major gradients (+324 metres / -338 metres). It is an easy and pleasant stage, with only a few slopes exceeding 10%.

State of the route: : Today’s stage is still one that pilgrims appreciate. There are more paths than tarred surfaces:

- Paved roads: 7.7 km

- Dirt roads: 11.1 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

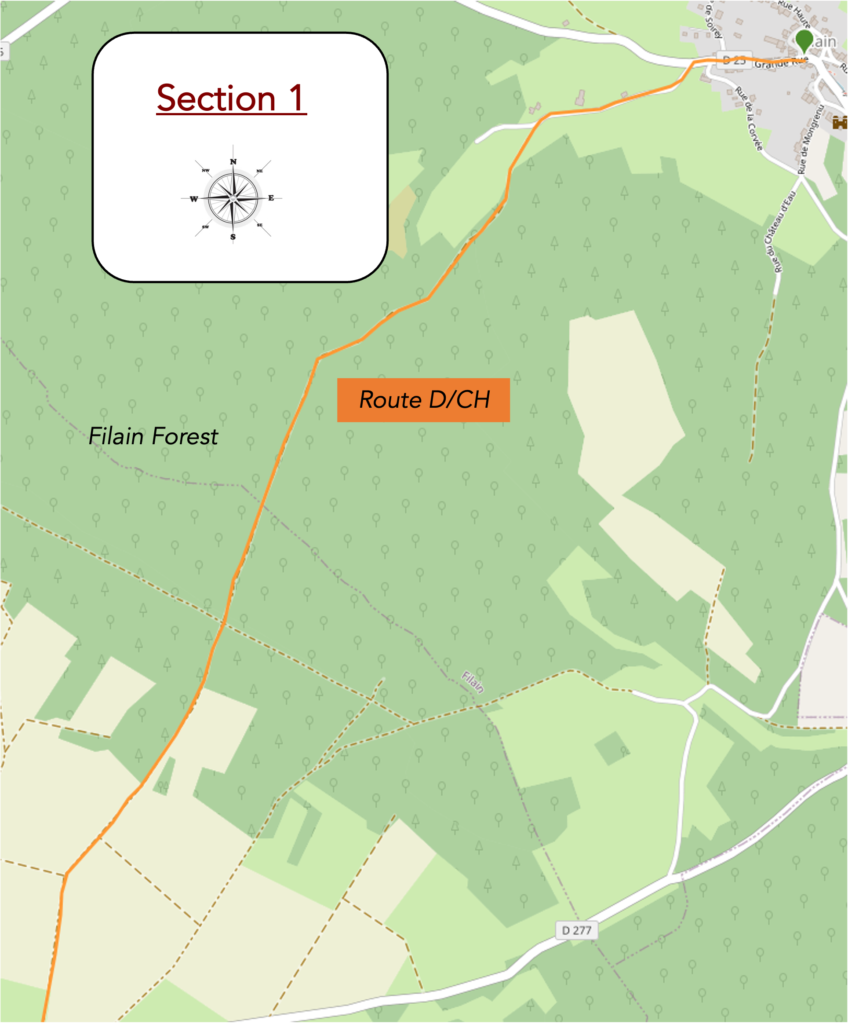

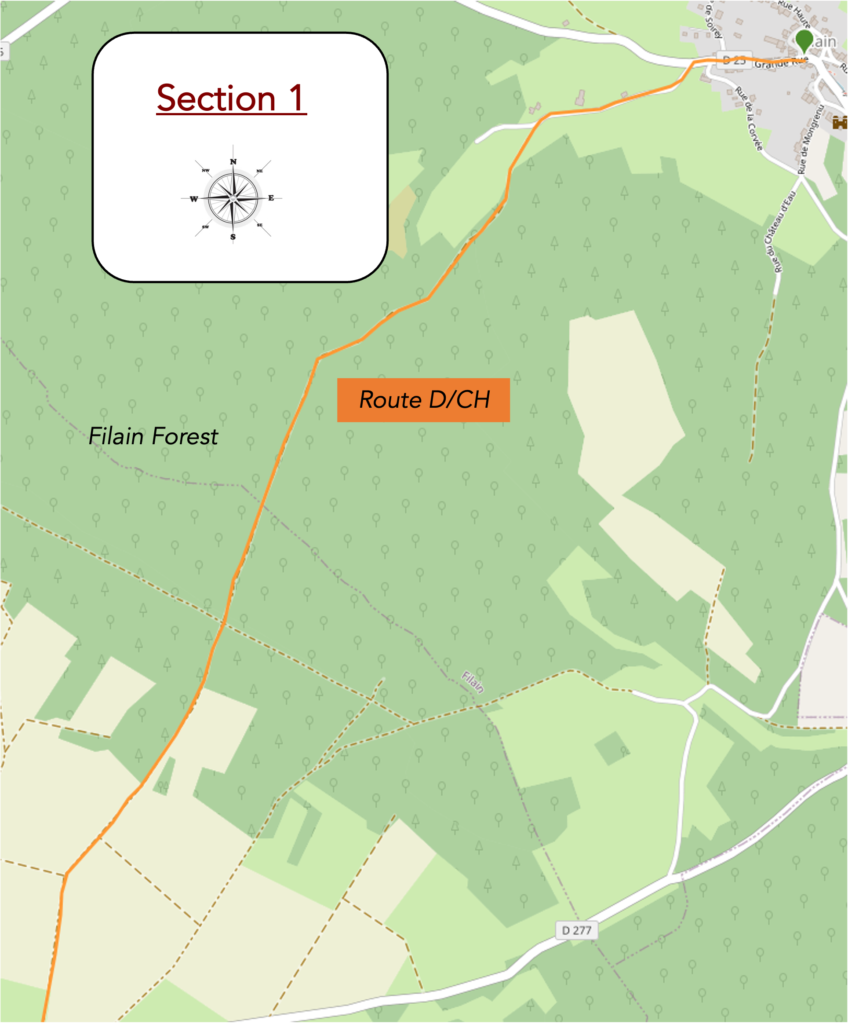

Section 1: In the Filain forest

Overview of the route’s challenges: route with no major difficulty.

| In Filain, it was unthinkable not to lead you to the foot of the château. It imposes itself naturally, with the calm majesty of ancient buildings, as if it had always been part of the landscape. |

|

|

| But the visit is brief, too brief, since the château is private property and its secrets remain carefully guarded behind its gates. So, the route resumes its way, rejoining the road that crosses the village below the church, in a gentle and quiet descent. |

|

|

| You walk slowly through Filain until you come upon a cross planted at the heart of a crossroads, like a compass frozen in stone, a landmark as spiritual as it is geographical. |

|

|

| There, near the inevitable Virgin, since here every village seems to have its Madonna watching over its inhabitants, the route leaves the village. It enters Rue du Chemin du Bois, an evocative name if ever there was one, like a promise of shade and coolness. |

|

|

| The road, still paved, then rises in a gentle slope toward the edge of the woods. Under the deciduous trees the light becomes muted, the air sharper, and steps feel lighter. |

|

|

| On a maple tree, discreet guardian of the route, the symbols of the route are fixed. There is of course the famous Compostela shell, always reassuring but badly oriented, as always in Franche-Comté, where the shell is only there to say that you are walking on the Way of St James. You must therefore trust the arrows and not the direction of the shell. There is also the yellow and red waymarking of a local path, bright in colour, reminiscent of GR routes without actually being one. Red and white, no, here everything is a matter of nuance. Who really knows the origin of this path, or its exact destination. One likes to imagine that even the waymarkers do not know. Why so much complexity and mystery in a land that is otherwise so simple? |

|

|

| Higher up, the tarmac gives way to a wide stony path, more rustic and more authentic. It is bordered by patient traces of human labour, piles of wood perfectly aligned, drying in the sun, evoking both the rigour and the slowness of forest time. |

|

|

| The path then enters a more open forest where the trunks leave the gaze free to wander between light and shadow. |

|

|

| And what a forest it is. It is truly beautiful here. The beeches, always the beeches, rise like natural pillars, slender and smooth, while a few sturdier oaks are scattered here and there like tired lords. A glance at the woodpiles along the path is enough to recognize species, textures, scents. Here the forest is not abandoned. It is tended, worked with care, respected. You can feel the hand of humans, but a careful hand, almost a companion. |

|

|

| Farther on, the path, until now almost as straight as if drawn with a ruler, begins to curve. It becomes narrower and more hesitant, as if suddenly becoming aware of its own line. |

|

|

| Shortly after, you finally leave the wide track for a more intimate trail that slips between the trunks with suppleness. It undulates through the undergrowth, following the light folds of the forest like a loose thread of wool on old fabric. Everywhere the shell confirms that you are on the right way. It is badly drawn, but the arrow shows the right direction. |

|

|

| Cyclists can also pass here, at least in theory. It is hard to imagine there are many of them. This trail is not made for speed or performance. It is slow, muffled, almost introspective. |

|

|

| And so much the better. The walk becomes beneficial, almost meditative. Under the beeches, some plump and pot-bellied like old dignitaries, others thin and nervous like adolescents stretched too fast, you advance gently. |

|

|

| Footsteps grow quieter on the carpet of leaves and the gaze loses itself in shades of green and grey. |

|

|

| The trail leads you effortlessly to the far end of the wood. A great beech forest spreads here, majestic and simple at the same time. You look in vain for hornbeam, so common along French paths, but no, in Franche-Comté it is the young beech shoots that create the undergrowth. Less charming perhaps, but more robust and frank. |

|

|

| Soon the path leaves the forest… |

|

|

| It then follows its edge, brushing the boundary where meadows and fields begin to dominate. |

|

|

| And here, let us admit it, the charm works less well. For if the forest is noble and welcoming, the open country sometimes has an air of polite abandonment. Flat fields, silent ploughland, functional crops without grace. One might tactfully call the landscape discreet, monotonous, or bare, rather than say it is a little dreary. May the local people forgive us. The walker senses that the poetry has slipped away. |

|

|

|

|

| Farther on there is only the solitude of large fields, an ocean of golden ears of grain or sunflowers turning their backs on everything. A kind of rural silence without birds and without tractors. You advance between wheat and sky. In these soulless fields where the earth stretches to infinity without break or fold like carefully ironed cloth, the landscape moves forward without relief, like a pale dream from which only the taste of forgetting remains. Nothing appears, nothing awakens you. Nostalgia seeps quietly between your steps. You then walk as you breathe, more out of necessity than desire, eyes lowered, counting stones or furrows, seeking the slightest thrill in the landscape, a hedge, a twisted tree, a ripple of land, anything at all. But nothing comes. In the distance, Authoison slowly takes shape at the end of the plain, like a promise, but still a distant one. |

|

|

Section 2: Endless fields before the return of the forest

Overview of the route’s challenges: a few steeper slopes in the woods.

| After this long stretch that more than one walker will readily consider a chore, at the end of the plain the path draws closer to a patch of woodland like a promise. Life seems to return. |

|

|

| Then a small road winds between woodland and open country, toward Authoison. |

|

|

| Authoison will no doubt be for you no more than a moment frozen on a large silent square, bordered by a plain town hall, a war memorial nobody looks at anymore, and the church of Saint Étienne from the eighteenth century, whose lantern tower, so typical of Franche-Comté, rises like a mute prayer, discreet yet persistent against the neutral sky. |

|

|

| At the far end of the square the route turns and enters Rue de la Manthe. Shortly after, as always and everywhere, a cross stands. Unmoving, as if every path in this region had to be sanctified and marked by a sign. The granite resists the wind there, and faith perhaps resists forgetting. |

|

|

| A road then runs alongside the cemetery, a silent mirror of the living. Opposite, new housing estates spread without restraint, laid down as one spreads playing cards on a table that is too old. The balance is fragile and the aesthetics questionable, but life goes on even when it sometimes scribbles over beauty. |

|

|

| But once these buildings are passed, nature takes back its rights. The road approaches the foot of the forest along a path called Rue en Belombre. An invisible border is crossed, behind you the built world, ahead the realm of vegetation. |

|

|

| A steady climb of about one kilometre then opens through the undergrowth. The slope changes but never brutally. |

|

|

| The trail is modest, narrow and often sunken, as if the trees themselves had drawn closer to protect it. The ground, with few stones, receives your steps with kindness. Here silence becomes a substance. Beech reigns supreme, natural colonnades of a sylvan cathedral. A few oaks and a few maples accompany them, but conifers have no say here. There are no needles and no scent of resin. You walk in a kingdom of broad-leaved trees, at the heart of a vegetal theatre without useless ornaments. From time to time badly oriented shells remind you that you have not lost your way in this mysterious wood. |

|

|

| At the top of the climb the path joins a forest road. |

|

|

| The small road yields to the slope. The descent toward Qenoche begins, sometimes steep yet always harmonious, like a natural slide into rest. The forest keeps its sovereign calm. Everything here breathes peace, as if each trunk stored a reserve of silence. |

|

|

| Then gradually the leaves open and the light returns. The undergrowth dissolves and the road slowly leaves the forest. This road is straight like an injunction. Its slope is clear and undeniable. There is no room for imagination or for a dreamy pace. Here you move forward, that is all. |

|

|

| At the bottom of this forest descent a hunters’ lodge stands beside the road. If chance is on your side, you will hear the dogs, hidden behind the fences, barking their impatience or raw joy. Their voices echo like something ancient, an animal memory that still vibrates in the woods. |

|

|

Section 3: The national road N19 must be crossed

Overview of the route’s challenges: route without major difficulty.

| At the edge of the woods the road stretches lazily across the wide farmed lands, slipping between neat rows of sunflowers whose heavy heads seem to be meditating on some obscure thought, and golden grain bending in the wind like a sea frozen in silence. Nothing disturbs this vast scene, apart from the persistent impression of suspended time. |

|

|

| The slope becomes gentle, almost imperceptible, and the road glides toward the entrance of Quenoche, a humble and discreet hamlet set in a landscape where even the hills seem hesitant to exist. |

|

|

| At the end of this short descent a crossroads appears, marked, like so many others in the region, by a solitary cross standing like a centuries-old witness, silent guardian of a world that no longer quite knows what it prays for. |

|

|

| The village allows itself to be crossed without resistance. The road winds peacefully past the church of St Julien, dating from the late eighteenth century. Its austere outline rises like a last baroque breath in a world that has become too functional. |

|

|

| The route leaves the village near the cemetery, bordered by a low fence behind which headstones worn by time stand in rows. And once again, like a familiar refrain, the Virgin, wrapped in her eternal blue and white, keeps watch. Nothing seems able to escape her fixed gaze. |

|

|

| Very near, the rumble of the N19 can already be heard, a major artery indifferent to everything around it, a taut line between Besançon and Vesoul that trucks devour at full speed without ever stopping. |

|

|

| It is enough to cross it and you enter Hyet. |

|

|

| The crossing of the village stretches out, slow and laborious. Old houses are rare, erased by the spread of recent housing estates that look as if they have escaped from some distant suburb. One senses here a silent change, almost melancholy. |

|

|

| The road climbs continuously and the higher you go, the more demanding the slope becomes, reaching a notable ten percent. Legs grow heavier and the breath shorter in this village that seems to cling to the hillside. |

|

|

| At the top, at last, the Way of Saint James leaves the asphalt and enters Rue du Théâtre, avoiding the road to Fondremand. A poetic name, almost ironic, since everything here appears frozen, without scenery, without audience, without reply. |

|

|

| The road runs the last ripples and housing developments of the village. |

|

|

| It runs near a reservoir and then sets off into open countryside, lingering near large farms that resemble hangars, where the lines of the landscape fade in the light. |

|

|

| Footsteps grow quieter on the carpet of leaves, and the gaze drifts away into the shades of green and gray. |

|

|

| At first a little freshness remains, offered by a few ash trees and scattered copses. They are the last companions before the dryness of a space without contours. |

|

|

| The path, wide and stony, moves forward between meadows, sometimes guided by hedges of broad-leaved trees, sometimes left to the indifference of a bare horizon. |

|

|

| It is a ribbon of earth fading endlessly through grasslands empty of any kind of crops before descending gently toward a large barn tucked into the discreet corner of a wood like a peaceful animal keeping to one side. |

|

|

| Then it climbs softly, as if reluctant to disturb the quiet of the place. |

|

|

| Little by little nature seems to close in again. The path, drawing nearer to the forest edge, leans with quiet gravity toward the welcoming shade of the trees. Soon the forest as a whole announces itself, ready to absorb the walker once again into its murmurs, its hidden trails and its different sense of time. |

|

|

Section4 : In the forest of La Grande Vallée

Overview of the route’s challenge: slopes sometimes steep, both uphill and downhill.

| The climb begins again along the edge of the forest, where the ground becomes rougher and the roots more visible, as if nature wished to remind you that it does not let itself be crossed without effort. The path rises with a determined rhythm, though without brutality, a steady, continuous ascent, a pace that you eventually accept as another form of breathing. |

|

|

| And then suddenly the lords of the woods appear, the beeches. Majestic and commanding, they rise toward the sky in a pure upward movement. Their straight trunks, almost smooth, in shades of pearl grey, lift endlessly like the pillars of a pagan temple. Their dense foliage, gathered into natural vaults, softens the light into a gentle green glow, almost liquid. |

|

|

| Here the Haute-Saône reveals its discreet wealth, a forest that feeds, protects and warms. Wood here is not only a material, it is a culture. For centuries woodcutters have found in it a noble profession. The piles of logs regularly stacked along the path speak the ancient language of the winter to come. The oaks, too, join in, shorter and more twisted, reminding you that it takes time to become strong. |

|

|

| The path softens again. It winds quietly, almost pleased with its fate, level through this generous forest. One has the feeling that nature here is accompanying you rather than testing you. |

|

|

| But suddenly you must turn. The wide path gives way to a more discreet and intimate trail, like a confidence the forest whispers to an attentive traveler. Be alert, the transition happens without noise. |

|

|

And there on a tree, just around a trunk, it is there, the scallop shell. Discreet, weathered by time, reassuring like a blessing. It tells you that you are indeed on the Way of Saint James, even if it does not indicate any direction. Here in the silence of the beeches it shines like a modest star at the heart of the greenery.

| Under these ever-sovereign beeches your pace becomes peaceful again. A sense of fullness settles in. The world fades. Only the leaves remain, the filtered light, and the almost religious breathing of the living forest. |

|

|

| The trees form royal avenues for you. |

|

|

| Soon the trail crosses an area that is denser and wilder. |

|

|

| The bushes brush against you, the tall grasses gently scratch your legs, and you feel here a freer nature, less ordered, almost unruly. |

|

|

| Fortunately, it is only a passage. Very soon a wider path restores a clearer harmony. The wood becomes mixed and more open, with shafts of light and varied species. The eye rests there, as does the breath. The rhythm of walking settles into the rhythm of the place. |

|

|

| Along this section you may meet a few cyclists, more numerous here than walkers. The path is made for it, smooth and pleasant, between sun and shade. |

|

|

| Yet nothing is ever fixed. Once again, the path changes. It turns, bends like a supple serpent and begins to descend into the undergrowth. |

|

|

| The slope, discreet at first, gradually establishes itself without harshness. It seems almost like a companion, guiding you through this peaceful descent. |

|

|

| Lower down, however, it becomes serious. The gradient approaches 15%, yet the ground remains firm and the step secure. Nothing here is trying to trap you. Even when steep, the path keeps its gentleness. |

|

|

| Then suddenly you leave the Bois de la Grande Vallée. Behind you lies that long forest crossing, that procession of trunks, foliage and shifting shadows. A world that has passed through you as much as you passed through it. |

|

|

| Ahead of you now a straight and stony path, almost abrupt in its rectitude, draws you toward the road between Hyet and Fondremand. |

|

|

| And there in the distance the village finally appears, Fondremand. Its name still floats in the air like a promise, but you have not reached it yet. This arrival must be earned. |

|

|

| The road then crosses calm countryside carpeted with meadows. Here tranquillity reigns. Cars are rare and only the curious or pilgrims dare disturb the silence. |

|

|

| These are mostly meadows, with their quiet herds of cows, mossy fences and a few still ponds. Crops keep a low profile as if they had not yet found their place here. |

|

|

| And here is Fondremand. The sign confirms it, but above all it is the atmosphere that tells you so. You are entering a “village of character,” and the term is no exaggeration. |

|

|

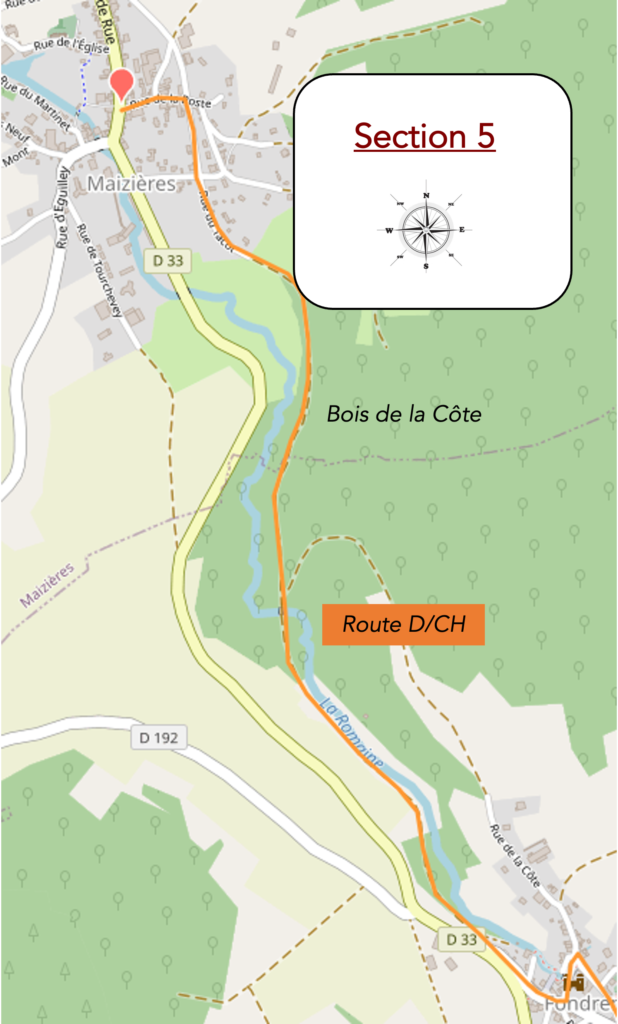

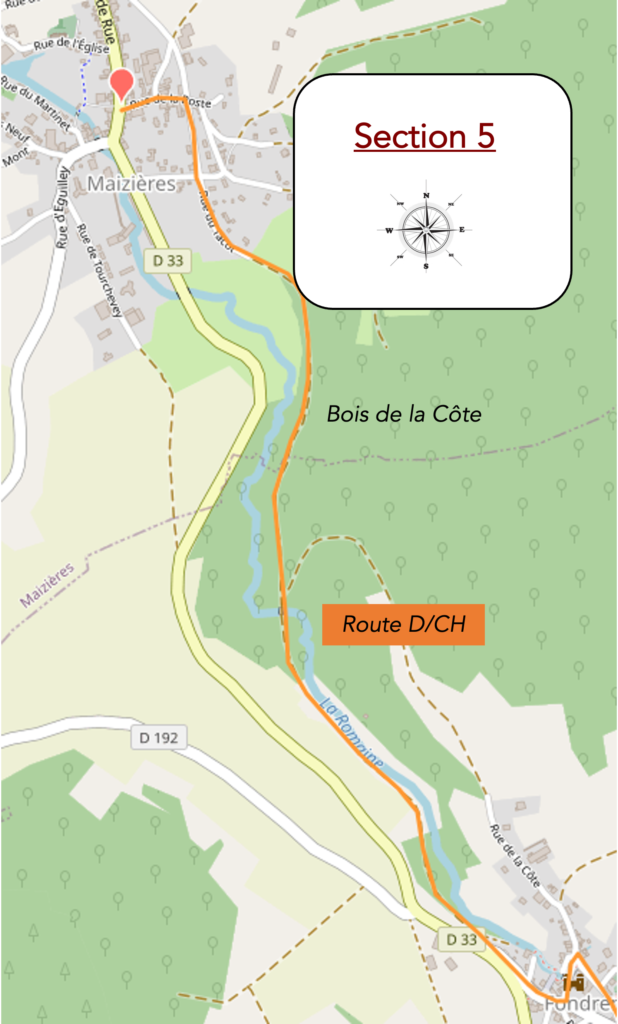

Section 5: Along the Romaine brook

Overview of the route’s challenge: route without difficulty.

| Fondremand is without doubt the jewel of the route, the most captivating village that Franche-Comté can offer to the traveler who walks with backpack and open heart. It is a place that seems to have slipped out of time, held in a calm beauty, almost meditative. Stone worn smooth by centuries, roofs with a serious pitch, an inhabited silence, everything here breathes history and the modest grace of places that have nothing to prove. |

|

|

| To reach the heart of the village you must climb Rue du Château, a gentle ascent yet a symbolic one, like a small inner pilgrimage. |

|

|

| Up there the church and the château share the summit, neighbors in eternity. The Church of the Nativity of Our Lady, built in the twelfth century, rises with the robust simplicity typical of Romanesque Franche-Comté. Sadly, its doors are often closed, a sadly familiar reality along the Way of Saint James where so many sanctuaries, deserted by the faithful, remain locked for lack of hands to open them in the morning and close them in the evening. |

|

|

| Of the medieval château, built at the end of the fourteenth century, only the keep tower remains today, massive and restrained, rectangular in plan. It overlooks a courtyard bordered by solid stone buildings from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The whole strikes by the unity of its construction, rare and precious. Nothing seems discordant. Every wall and every stone seem to have been in its place forever, as if time itself had respected this balance. |

|

|

| JJust below this noble architecture the source of the Romaine murmurs in the shadow of the stones. The Romaine, a modest tributary of the Saône, does not actually rise here but two kilometers upstream. Yet in Fondremand it offers a rare spectacle, an almost sacred scene. The water emerges gently from the belly of the earth, from a stone trough, bubbling with a living slowness as if the earth itself were breathing. It is a place where one stops naturally, drawn without willing it by the quiet presence of running water. |

|

|

| At the foot of the great tower, nestled in a curve of the path, an old washhouse sleeps, abandoned yet touching. One can easily imagine the figures of the past, women leaning over the laundry, chatting, rinsing, scrubbing in the gentle slapping of clear water. Today it serves no one, yet it remains there, a silent witness to a vanished daily life. |

|

|

| The river widens gently here and forms a small peaceful pond. |

|

|

| At its far end an old watermill still stands, flanked by an oil mill that has been out of use for two centuries. This building, now a private home, seems to keep in its thick stones the memory of ground grain, of turning millstones, of workers’ voices. Fondremand, with this rare combination of natural beauty, heritage and silence, is a genuine treasure, discreet yet radiant for those who know how to look. |

|

|

| Reluctantly the route leaves the village, not without one last pause on a small square arranged for visitors. One lingers, casting a last look back, as to a friend one leaves without knowing when one will meet again. |

|

|

| Here the route enters a forest road that seems to want to stroll for a long time in the shade of the Bois de la Côte. The river, a discreet companion, hides to the right in the hollow of the ravine, shy or perhaps mischievous, barely allowing itself to be glimpsed among ferns and low branches. This trail, like a whisper in the forest, unfolds with a bucolic nonchalance. |

|

|

| The walk then becomes a parenthesis of freshness beneath light foliage. |

|

|

| Young beeches send up their shoots like promises, while frail maples lift their delicate leaves like small hands stretched toward the light. The air is more humid here, filled with sap and moss and that green scent peculiar to deep woods. |

|

|

| From time to time a bluish flash or a shimmer betrays the presence of the river below in lush vegetation, almost tropical in places. It seems to follow its own adventure in parallel, free and elusive like a thought one cannot quite catch. |

|

|

| Then the path, as if to reconnect you with the mineral world, crosses old beds of schist. These dark layers, slowly carved by centuries and by the river, form a rough, striated ground on which the step sounds differently. Here you walk upon millennia. |

|

|

| A little further on, the river, in its usual discreet way, has crossed the path. One would not notice it without moving closer. But for the curious person who approaches to the right, a small spectacle appears. The water dances down over the schist slabs in happy cascades, laying out clear and joyful curtains as if it were dancing upon the rock. |

|

|

| Yet the path, faithful to its nature, leaves this watery scene without turning back. It continues level through the wood in a kind of calm indifference. |

|

|

| Gradually the forest thins. Shade retreats step by step and the path slips slowly out from under the cover. It is a gentle transition, like waking up. |

|

|

| Then the inevitable piles of wood reappear, trunks of beech and oak cut methodically and stacked with care, like sardines neatly aligned in a tin. They mark the territory of humankind, its presence and its usefulness. |

|

|

| Farther on, the route skirts the outskirts of Maizières. It is not a triumphant arrival, but a discreet infiltration into the margins of the village. You enter the human world by the edge of the road, a bit like pushing open a door without making a sound. |

|

|

| The route then reaches the departmental road at the entrance to the village. |

|

|

| There, like a welcoming gift, the Romaine flows softly, almost languidly, between two banks that hold it as a jewel in its setting. Its presence is soothing and musical. |

|

|

| The heritage has not been forgotten. An old washhouse has been preserved like an open book on the past, a silent vestige of days of hard work and conversation. It has that nobility of simple objects that have crossed the centuries without ever losing their soul. |

|

|

| The same cannot be said of the Roman statue of the village. It seems relegated, perhaps mistreated, absent or barely visible. The silence of stones sometimes becomes a form of oblivion. |

|

|

Official accommodations in Burgundy/Franche-Comté

- Hôtel La Charmotte, Quenoche; 03 84 91 80 54/ 06 48 16 70 63; Hôtel

- Hôtel La Romaine, 21 Grand Rue, Maizières; 03 84 92 31 24; Hôtel

Jacquaire accomodations (see introduction)

Airbnb

Each year, the route changes. Some accommodations disappear, others appear. It is therefore impossible to produce a definitive list. This list includes only places to stay that are located directly on the route or within one kilometre of it. For more detailed information, the guide Chemins de Compostelle en Rhône-Alpes, published by the Association des Amis de Compostelle, remains the main reference. It also contains useful addresses for the bars, restaurants, and bakeries that punctuate the route. On this stage, finding accommodation at the end of the day is difficult. It must be said that this region is not a tourist area. It offers other kinds of riches, but not an abundance of infrastructure. Today, Airbnb has become a new point of reference for travellers, and we cannot ignore it. It has become the most important source of accommodation in all regions, even in those that are not particularly touristy. As you know, exact addresses are not directly available. On this stage, accommodation is very limited. It is always strongly recommended to book in advance. Finding a bed at the last minute is sometimes a stroke of luck; it is better not to rely on that every day. When you make reservations, be sure to ask whether evening meals or breakfast are available.

Feel free to leave comments. That is often how one climbs the Google rankings, and how more pilgrims will gain access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 8: From Maizières to Gy |

|

|

Back to menu |