Between white wines and red wines

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

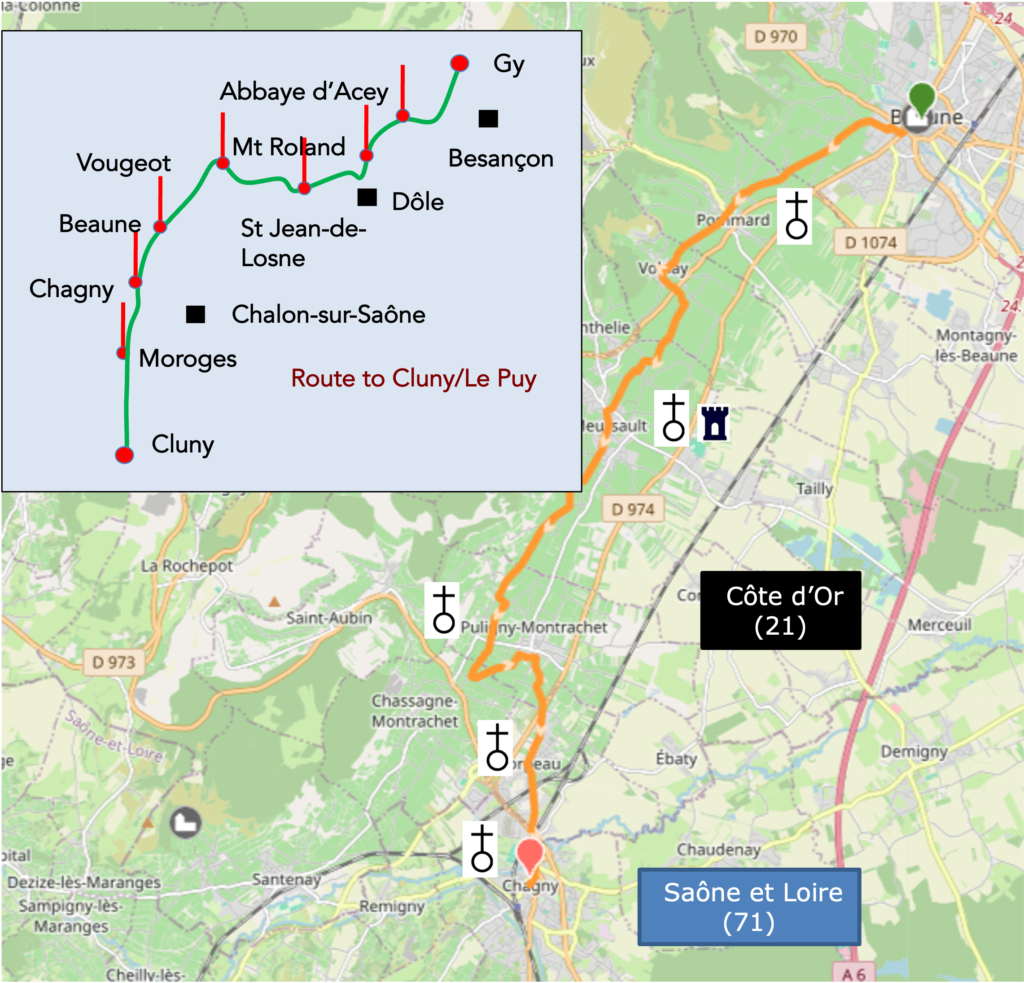

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

| This is obviously not the case for all pilgrims, who may not feel comfortable reading GPS tracks and routes on a mobile phone, and there are still many places without an Internet connection. For this reason, you can find on Amazon a book that covers this route.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page. |

|

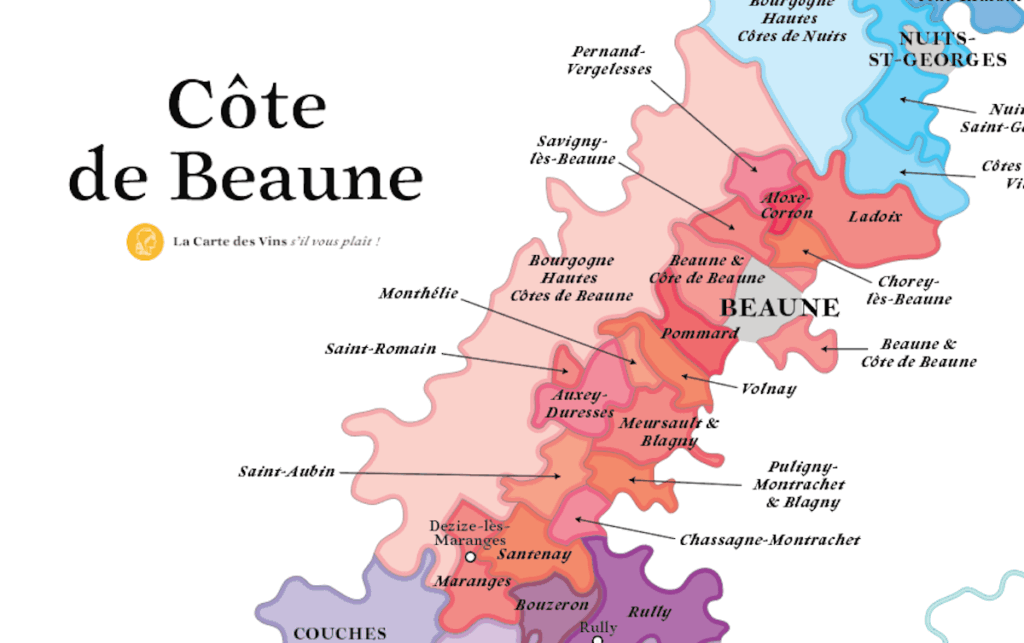

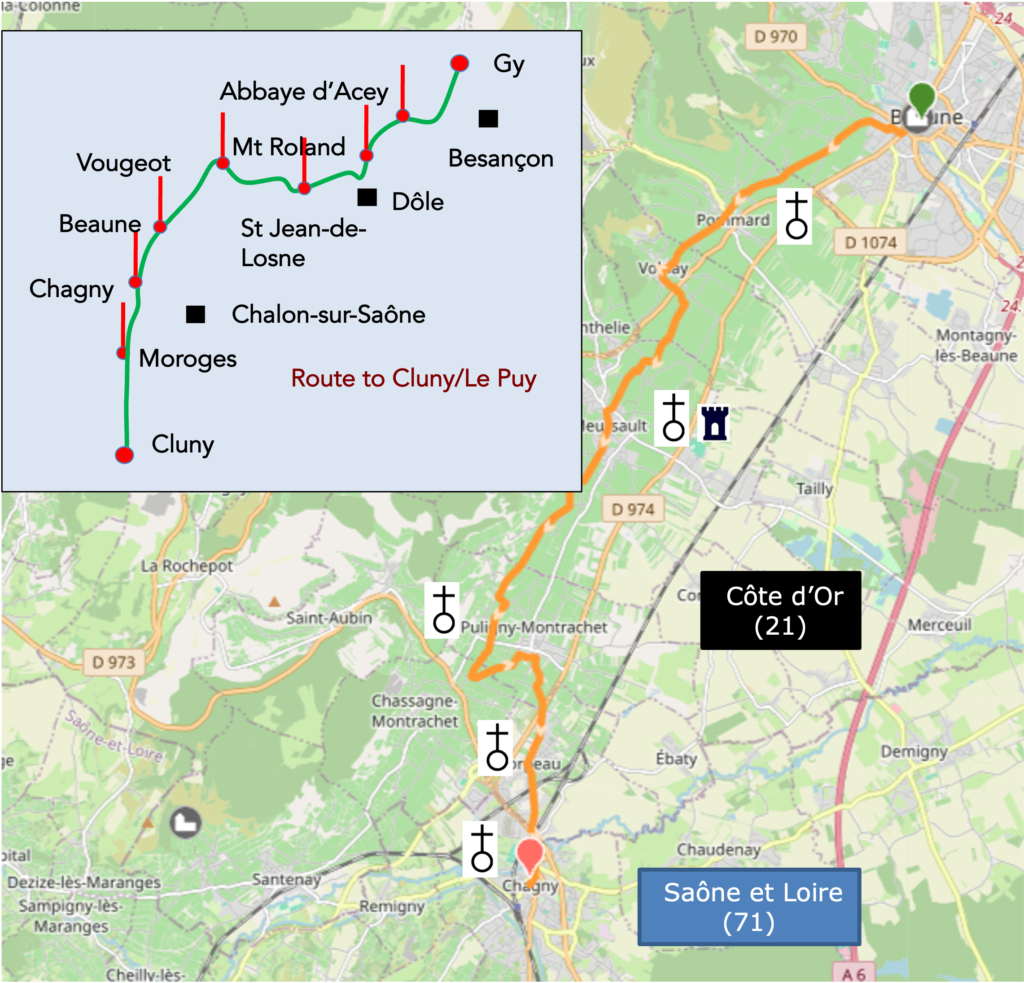

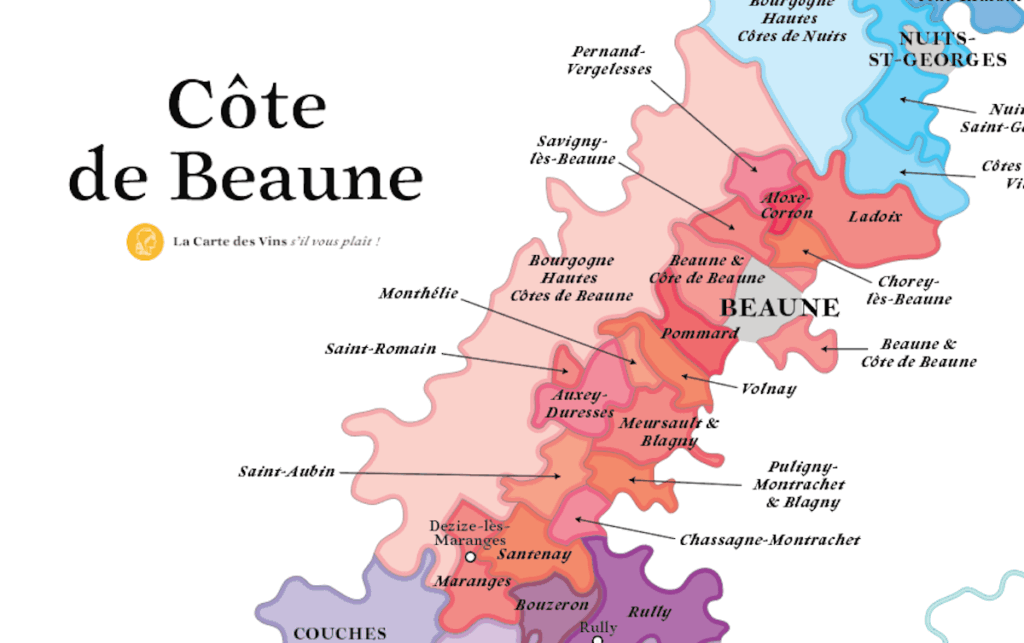

Between Beaune and Chagny stretches one of Burgundy’s most prestigious wine corridors. The journey follows a flowing ribbon of vines that dresses the hillsides like a living cloak, shifting in tone and texture with the passing seasons. Here, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay reign supreme, each revealing the singular character of the soils and exposures. The red wines, born of Pinot Noir, display deep garnet hues and release aromas of dark fruits and delicate spices, while the white wines, drawn from Chardonnay, feel almost revelatory, sometimes vibrant and mineral, sometimes broad and generous, with a lingering finish that seems to hold on to the light.

At the heart of this route rises Meursault, a true star in this vinous firmament. Its vineyards, gently sloping down toward the village, give birth to fleshy white wines that balance freshness with velvety texture, offering notes of honey, butter, and toasted hazelnut. The charm of Meursault lies as much in its wines as in the village itself, with houses of pale stone, centuries old cellars, glazed tile roofs, and a peaceful atmosphere that reminds visitors that wine here is not merely a product but a way of life, almost a form of breathing. Just a short distance away, Puligny-Montrachet and Chassagne-Montrachet complete this exceptional tableau. Puligny produces wines of crystalline precision, taut and luminous, counted among the greatest white wines in the world. Chassagne, for its part, unites generosity and finesse, crafting both rich and elegant whites and a handful of delicate red wines. Together with Meursault, these two villages form a legendary trilogy, a terroir of rare perfection where each cru becomes a summit. From Beaune to Chagny, passing through these villages, one does not merely travel a road, one walks through a living book, written by the land, the climate, and the hands of men. Each glass becomes a page, each vineyard a stanza, and the whole composes an ode to time and patience.

How do pilgrims plan their route. Some imagine that following the signposting will be enough. You will soon discover, sometimes to your frustration, that the signposting is often inadequate. Others rely on guides available on the Internet, which are frequently too basic. Some prefer to use GPS, provided they have imported the Compostela maps of the region onto their phone. By using this method, and if you are experienced in handling GPS navigation, you will not get lost, even though the proposed route is not always exactly the same as the one indicated by the scallop shell signs. You will nevertheless reach the end of the stage safely. In this regard, the site considered official is the European route of the Paths of Compostela, available at https://camino-europe.eu/. For the stage of the day, the map is accurate, although this is not always the case. With a GPS, it is even safer to use the Wikiloc maps that we provide, which describe the current marked route. However, not all pilgrims are experts in this kind of walking, which for some distorts the very spirit of the path. In that case, you can simply follow us and read along. Every difficult junction along the route has been clearly indicated to prevent you from losing your way.

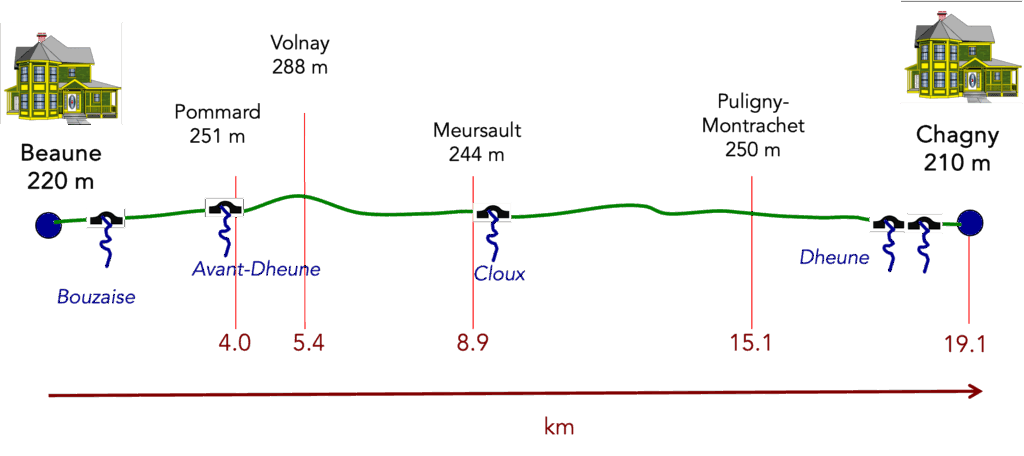

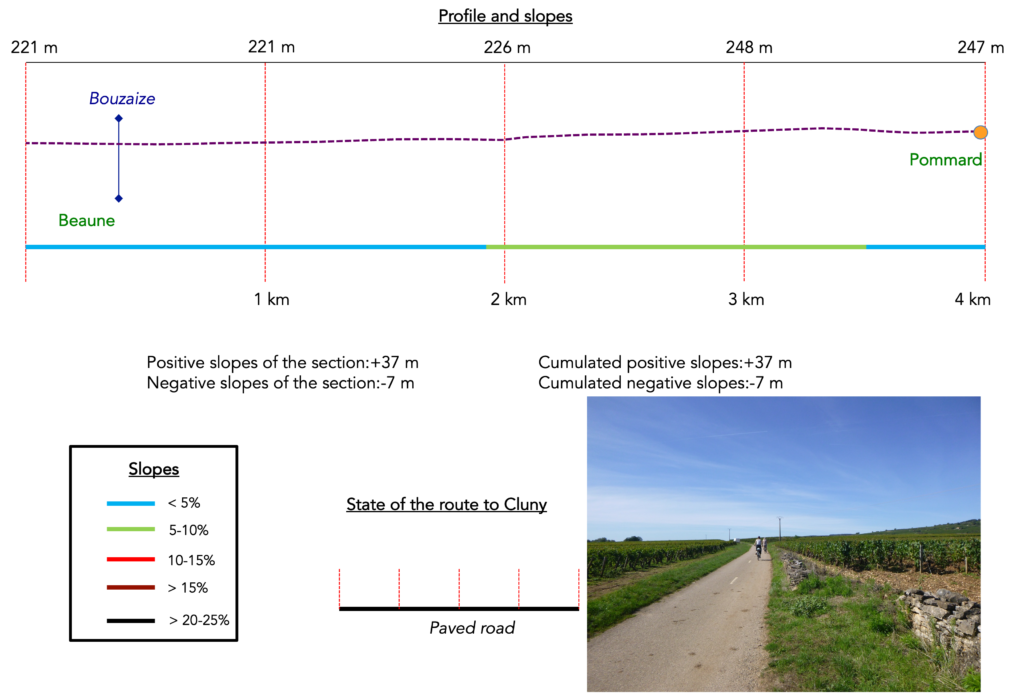

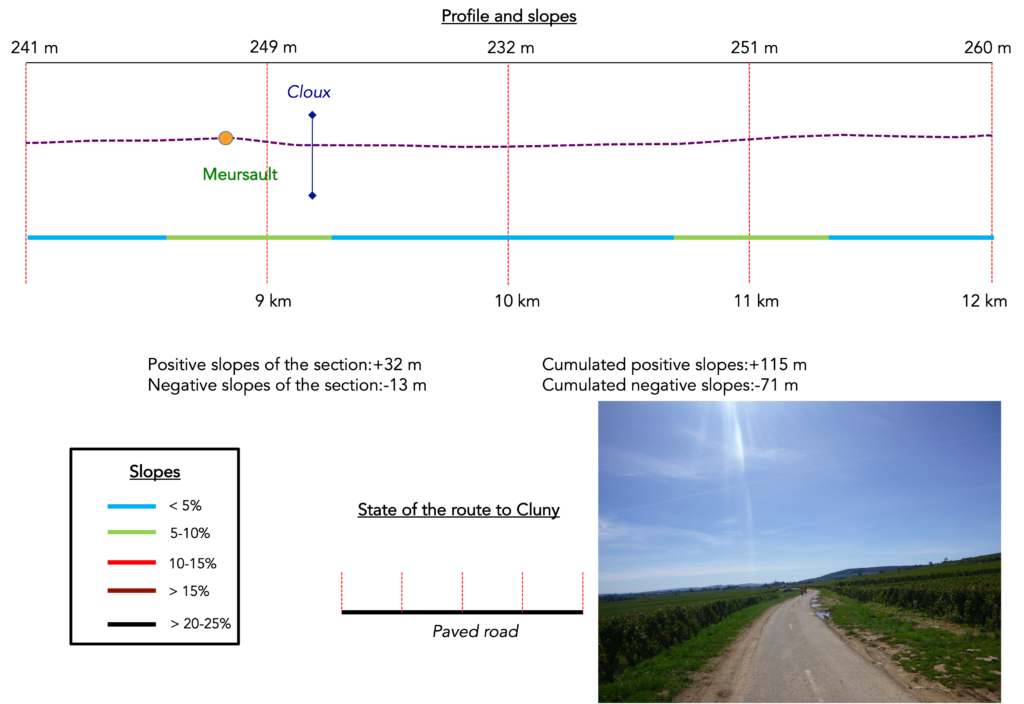

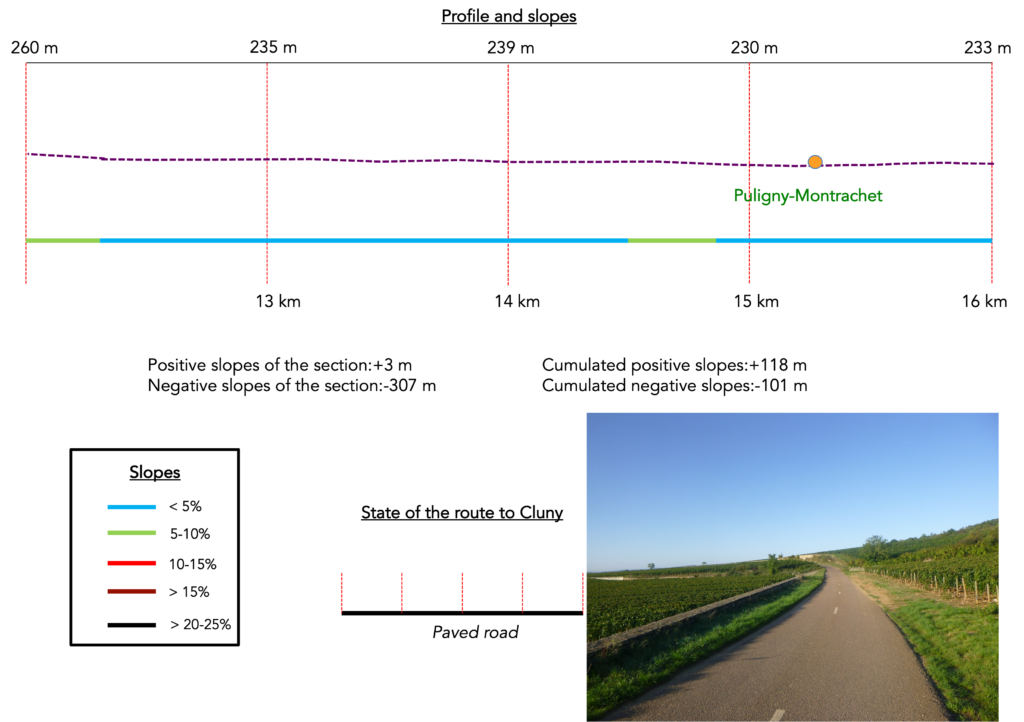

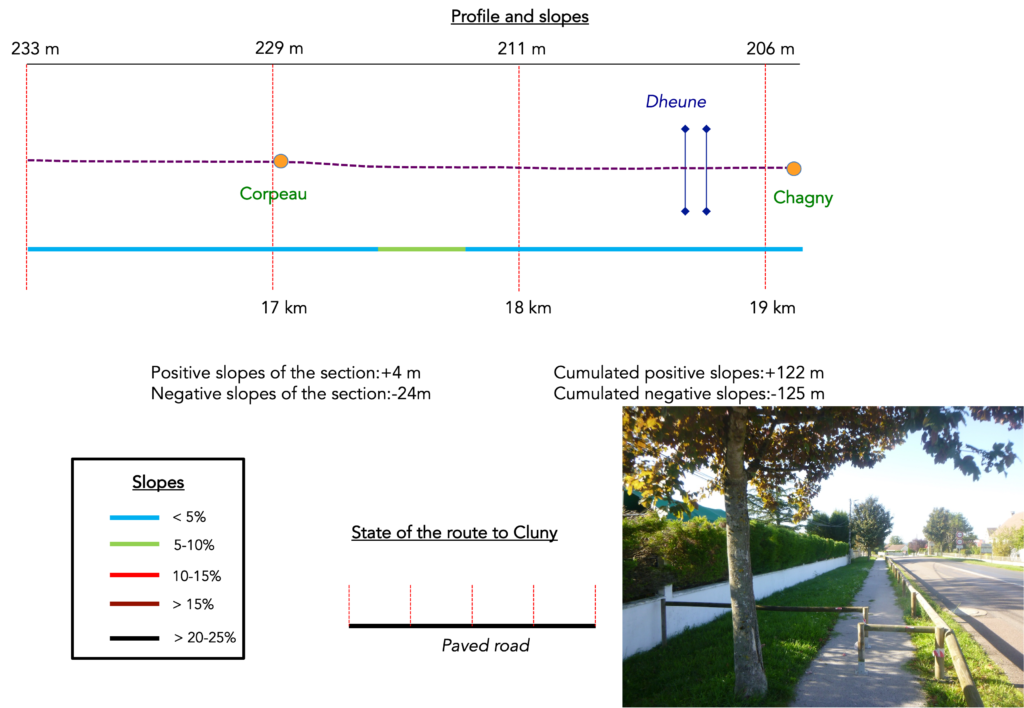

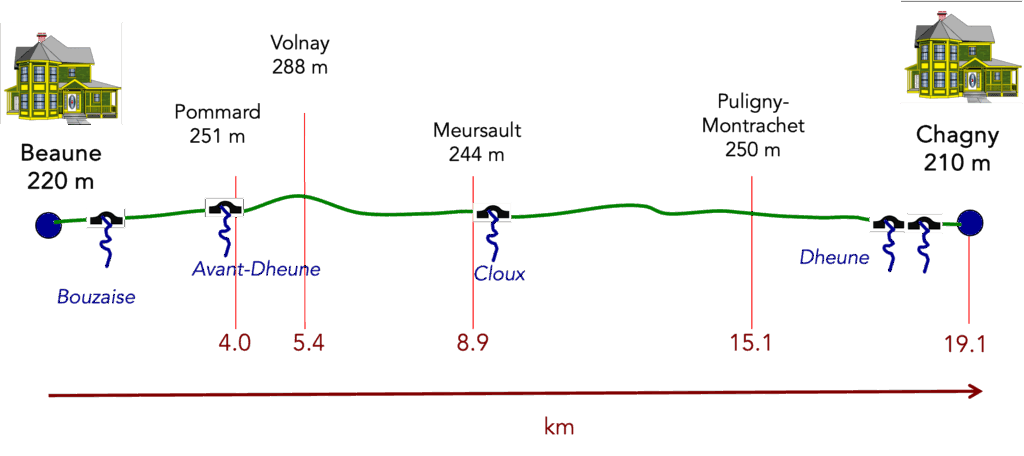

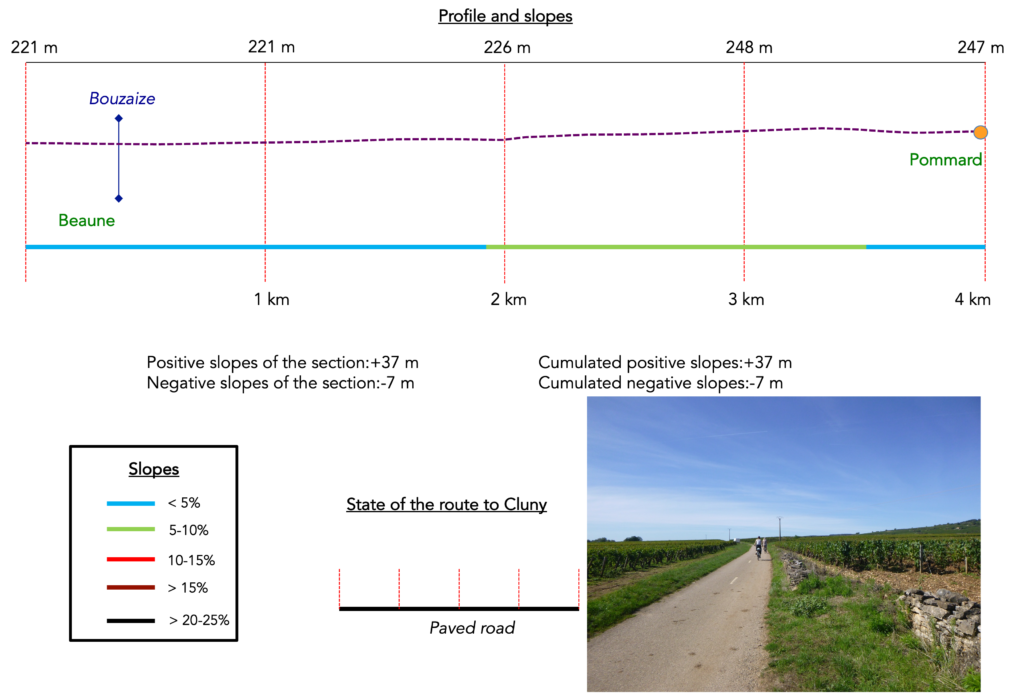

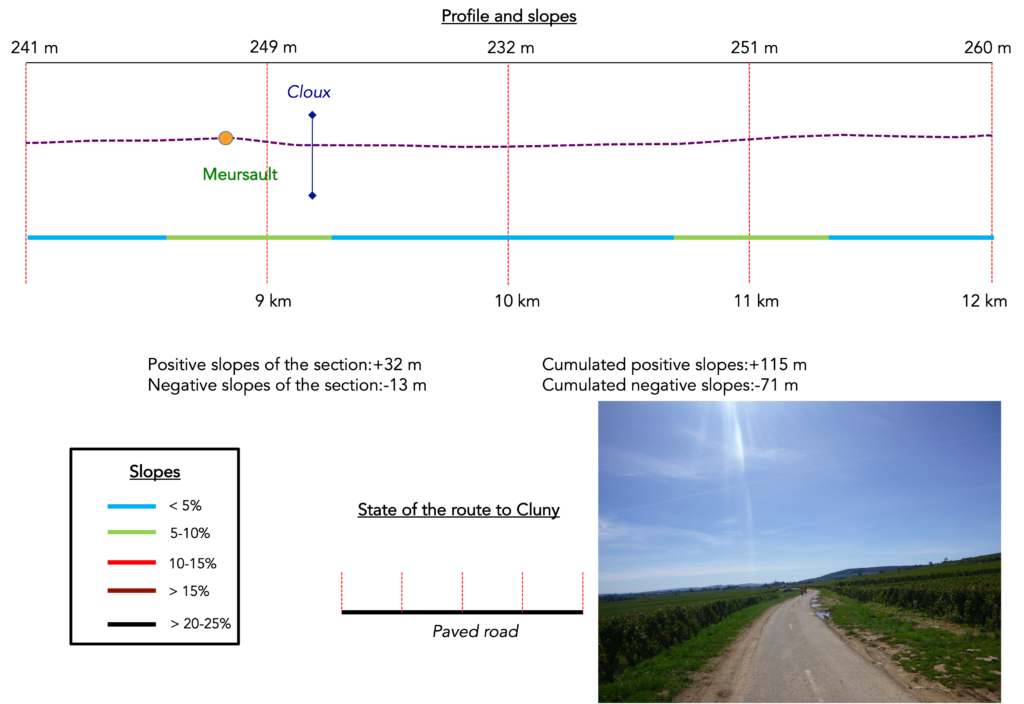

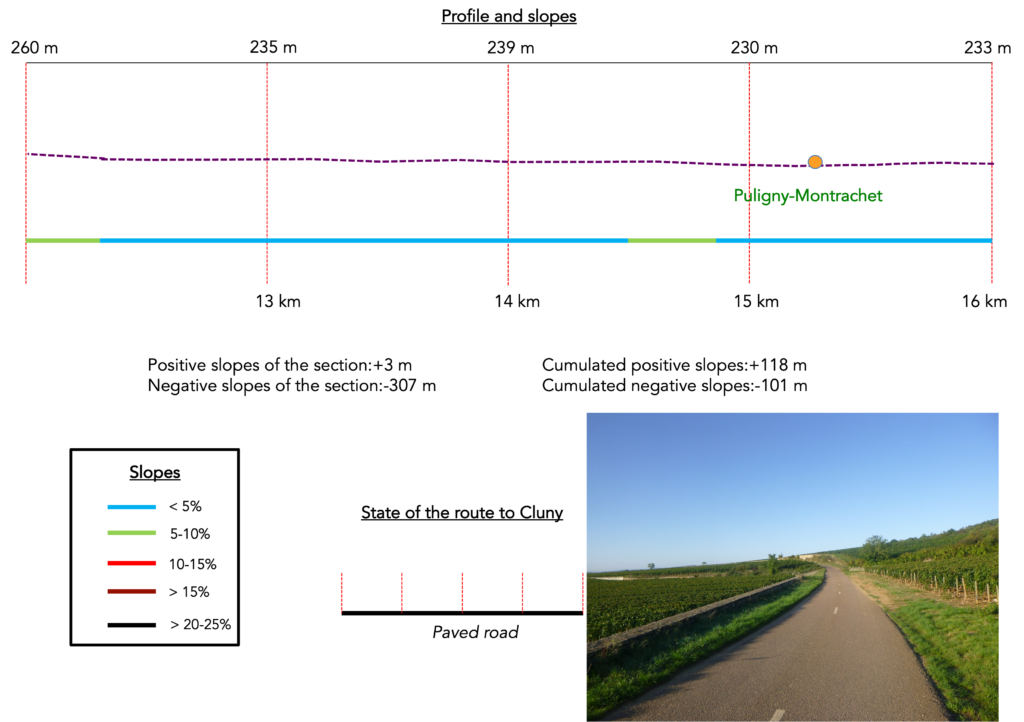

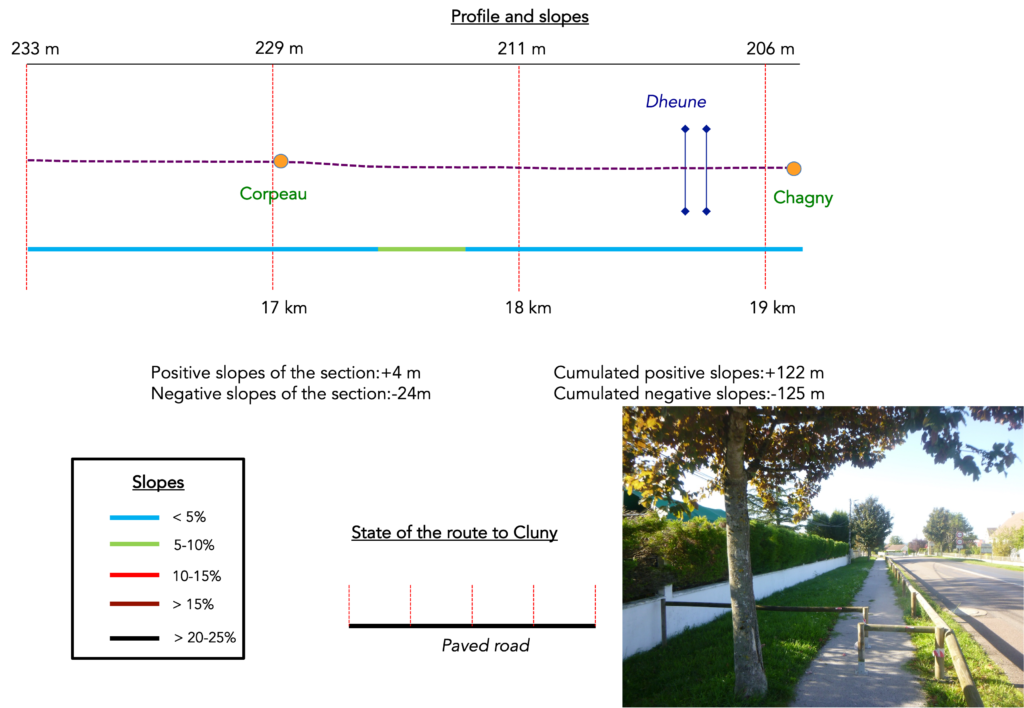

Difficulty level: The route presents no particular difficulty, with gentle elevation changes (+122 meters/-125 meters).

State of the route: Unfortunately, today the entire route runs on asphalt:

- Paved roads: 19.1 km

- Dirt roads: 0 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

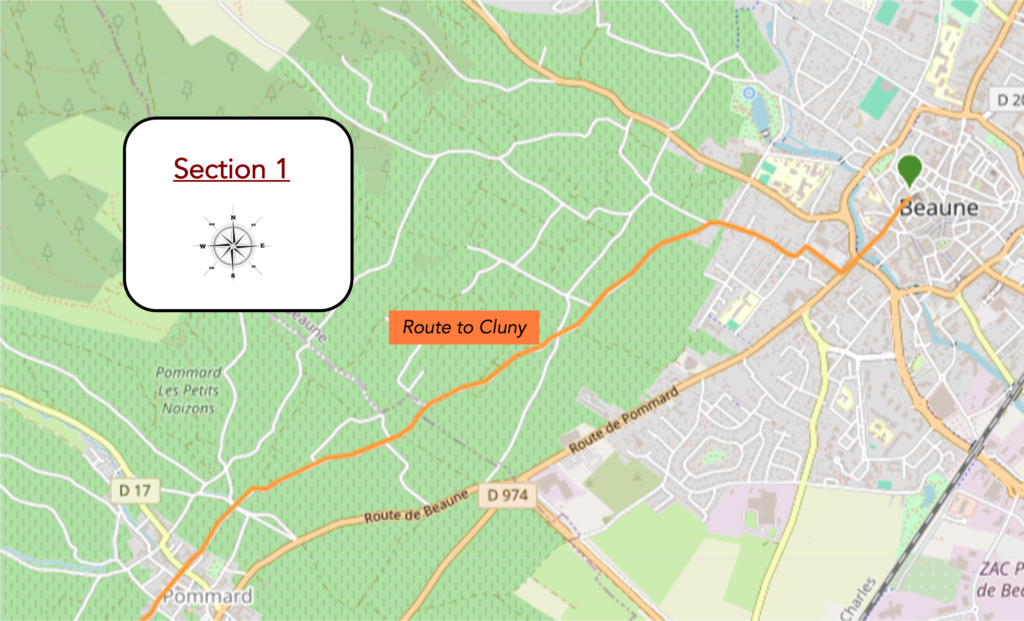

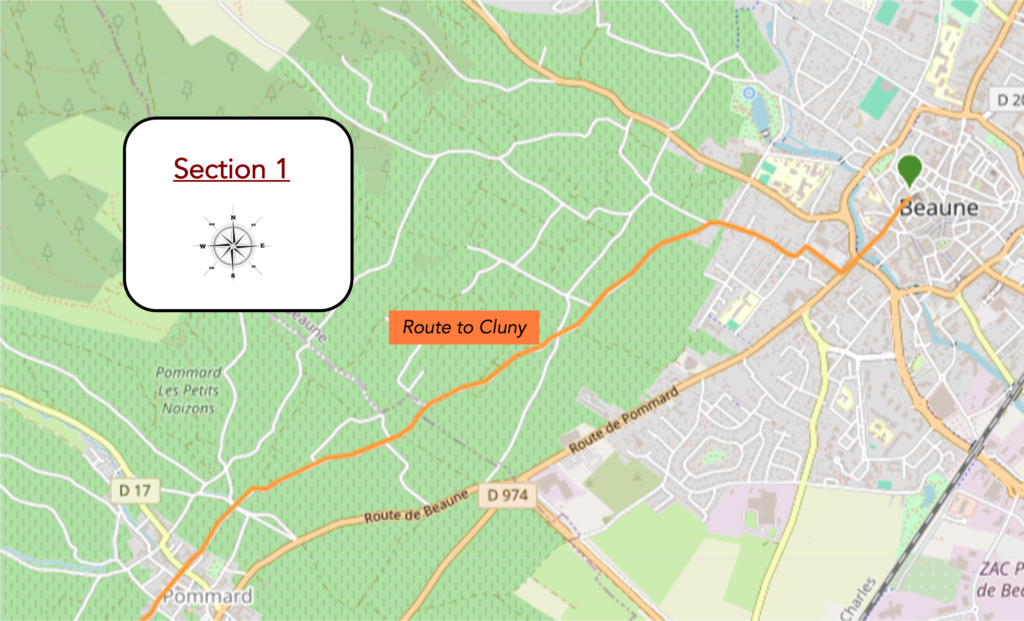

Section 1: In the Beaune vineyard

Overview of the route’s challenges: route without difficulty.

| The route sets out from Beaune at Place de la Halle, at the foot of the Hôtel-Dieu, that Gothic jewel whose glazed tile roofs shimmer like mosaics under the Burgundian light. Here, the walker leaves behind history frozen in stone and begins moving toward wine shaped horizons. |

|

|

| Soon, the route slips through Place Fleury, where shopfronts line the street and release a gentle urban bustle. Advancing along Rue Maufoux, the atmosphere slowly transforms. The noise softens, the façades grow farther apart, and the walker gradually withdraws from the pulsing heart of the town, as if Beaune itself were loosening its embrace with quiet reluctance. |

|

|

At the end of this progression, Boulevard Clemenceau rises ahead, a broad artery to be crossed before continuing straight on into Rue du Faubourg Bretonnière. Urban life still asserts itself here, steady and present.

| It is one hundred meters farther on that vigilance becomes essential. A discreet turn slips off to the right, Morlot Lane. Barely visible, marked only by the modest sign of a scallop shell, it easily escapes distracted eyes. Missing it condemns the walker to drift along the endless boulevard, like a ship drawn off course by an overly vast sea. |

|

|

| This narrow and almost confidential lane runs alongside the shadow of a large shopping center and the wide openness of a parking area. The contrast is striking. After the elegance of the old streets, the walker’s footsteps suddenly echo within the ordinary modernity of everyday life. |

|

|

| At the end of the lane, the route turns left for a brief moment, following Rue des Levées. Here, the marking becomes reassuring. Arrows guide the traveler clearly, as though the town itself wished to escort the walker gently toward its edge. |

|

|

| A little farther on, the road turns right into Rue des Verottes, at the threshold of the outskirts. The façades thin out, and one senses the boundary between town and countryside slowly fading, ready to yield to the first vineyard rows. |

|

|

| Then, suddenly, at the end of the street, the horizon opens wide. The vineyard steps forward, noble and generous, accompanied by a cycle path that winds like a ribbon among the vines. The walker understands that the urban crossing, brief and well-marked after all, was only a prelude to this long-awaited encounter with the vine. |

|

|

| The route finally reaches the gateway to the Beaune appellations. Here, the line merges with the cycle route, and the attentive eye recognizes the yellow and red markers of the GR76, a reminder that this major itinerary also shares the passage. The terroir already announces itself as a promise. |

|

|

The Beaune appellations extend across a vast and prestigious territory. Beyond the wines of Beaune itself, they encompass the renowned vineyards of Pommard, Meursault, and Puligny-Montrachet. The wines sold under the name of the Hospices de Beaune draw from these varied terroirs, reaching as far as the Côte de Nuits, giving each bottle its own singular brilliance. Farther south, the Beaune appellation itself stretches toward Chagny, where it hands over to the vineyards of the Côte Chalonnaise, like a sentence flowing from one region into the next without ever losing its breath.

| The cycle path slopes up gently through the heart of the vineyard, running alongside dry-stone walls that nobly delineate certain parcels. These low walls, centuries old witnesses to the labor of winegrowers, seem to guard the secrets of the vines they protect, like motionless sentinels watching over a sacred heritage. |

|

|

Farther on, the route reaches a crossroads of roads where attention becomes essential once again. Here, no scallop shell guides the walker. Only careful observation prevents error. You must resist the temptation of the GR76 signs that branch off to the right, climbing through the vines. This option, though alluring, also leads to Pommard, but along a longer and more demanding route, designed for those who seek exertion. The Way of Santiago continues straight ahead, faithful to the calm and even line of the cycle path.

| The paved path then carries the walker through the vineyard rows for more than two kilometers. The eye drifts along the orderly alignments, the breath grows light. Walking here means advancing without constraint, carried by the beauty of a landscape that offers itself without reserve. |

|

|

| On either side of the road, small granite walls rise again, discreet boundaries marking the richest parcels. Prestigious crus hide there, scattered like jewels within the vineyard’s setting, never fully revealed and always slightly secret. |

|

|

| Below, the plain unfolds, crossed by the departmental road running toward Pommard. The contrast is striking between the steady flow of cars and the unhurried pace of the walker, like two parallel worlds brushing past one another without ever meeting. |

|

|

| Soon, beyond a gentle rise, Pommard appears on the horizon, drawing closer like a promise. Its rooftops emerge through the lattice of vines, and already the traveler senses the welcome of a village shaped by wine. |

|

|

| The road then begins to wind in a few graceful bends, running alongside an imposing stone wall. Behind it, one imagines the shadow of a prestigious estate, perhaps one of those sanctuaries where wines are crafted that give Burgundy its enduring glory. |

|

|

| It is once again the soft, steady rhythm of the cycle path that guides your steps, like a peaceful line at the heart of the vines. It leads you straight toward the high wall of another renowned estate, whose massive stones murmur the echo of a long history. This wall seems to protect an invisible treasure, an enclosed garden one imagines filled with jealously guarded vines. |

|

|

| This near fortress wall defines the famous Clos de Cîteaux. Above it rises a small cross, slender and discreet, a sentinel that for generations has blessed the vines and watched over them. In its simplicity, it embodies the ancient bond between land, faith, and wine, an intimate union that has shaped Burgundy’s identity for centuries. |

|

|

| And here, at last, Pommard reveals itself to the walker. The village appears in the calm dignity of its stone, crowned by the reputation of its wines. After the crossing of landscapes and vineyards, arriving in Pommard feels like a reward, a long-awaited pause at the heart of a mythical terroir. |

|

|

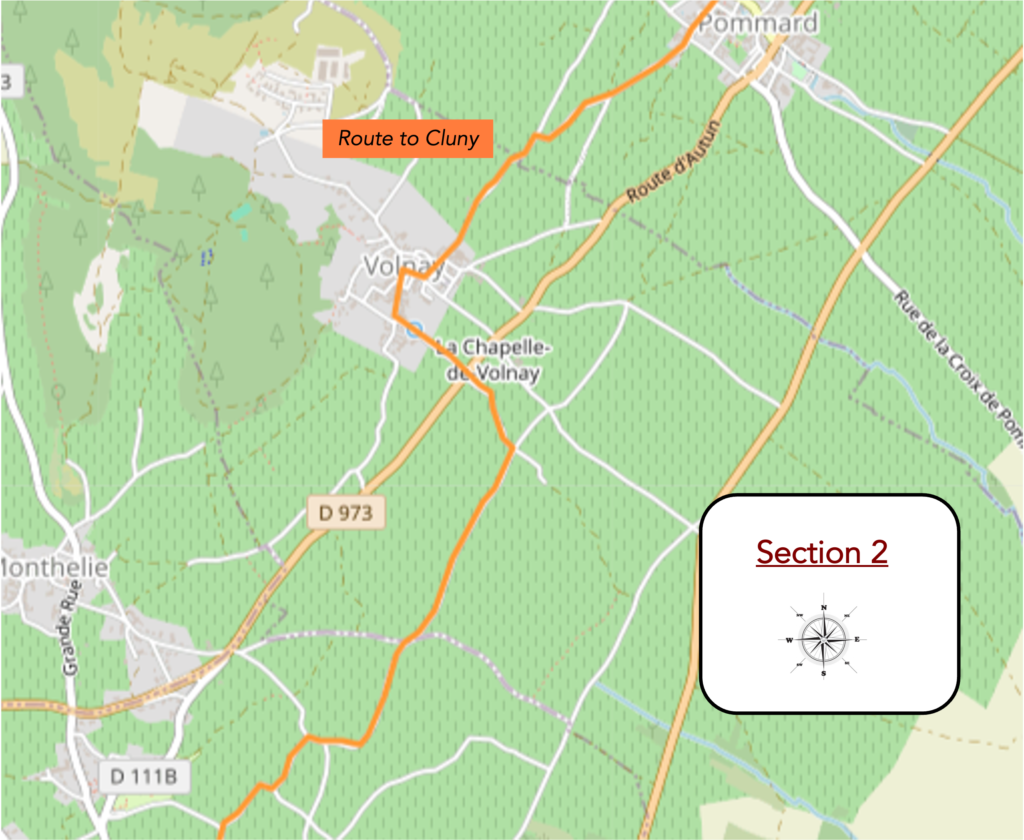

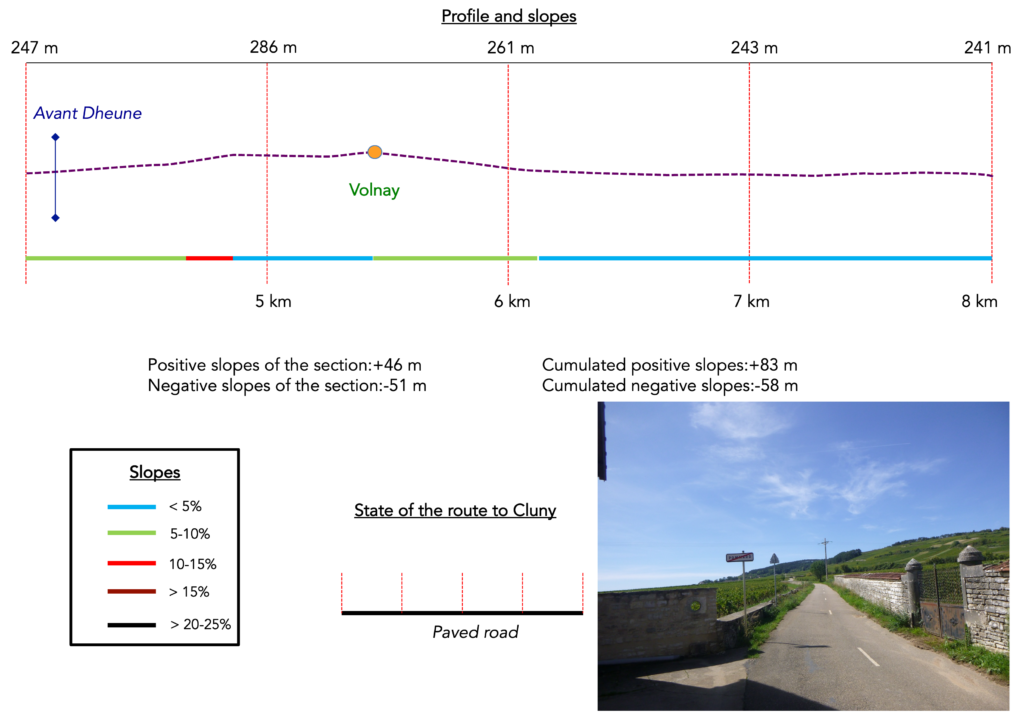

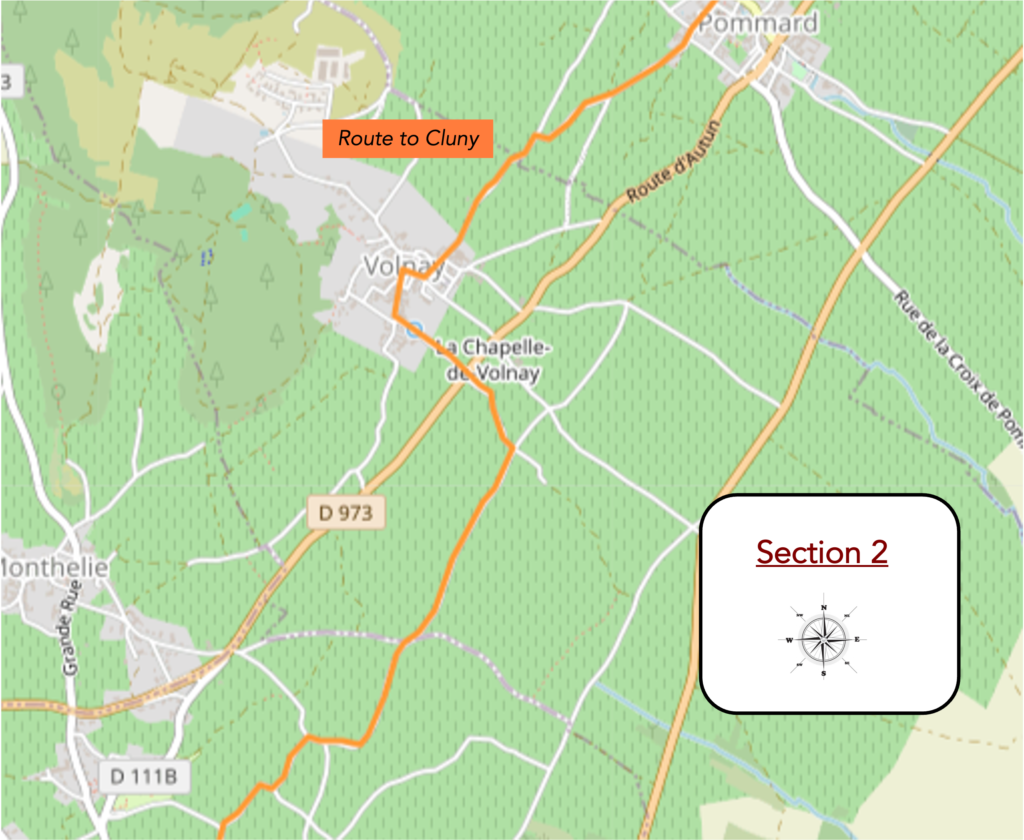

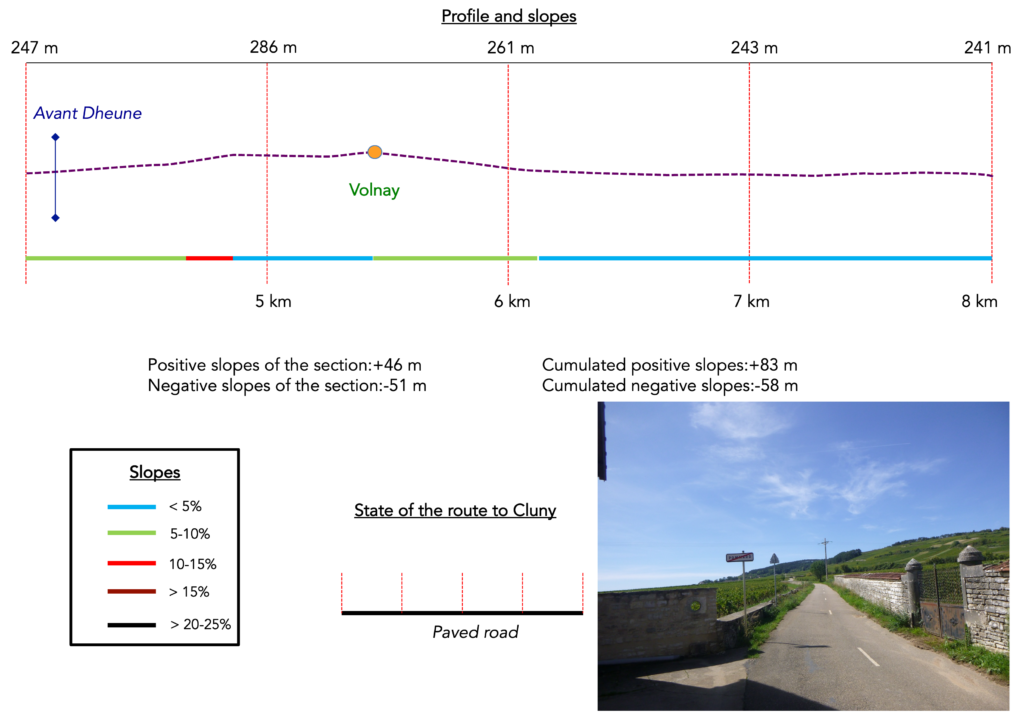

Section 2: In the vineyards of Pommard and Volnay

Overview of the route’s challenges: a slightly steeper route when climbing toward Volnay.

| A small road stretches ahead of a twelfth century château whose ancient stones, partly hidden behind scaffolding, still speak of the epic sweep of centuries past. At the time of our passage, the building bore the signs of renewal, with strengthened walls and refreshed roofs, as though time itself had agreed to loosen its grip and allow human hands to restore this witness of the Middle Ages. |

|

|

| The route then continues along Rue de la Refène, lined with sturdy winegrowers’ houses in warm ochre tones. Their solid façades, marked by the patina of years, reflect the hardworking spirit of generations of vintners who shaped both stone and wine with the same devotion. |

|

|

| Before long, the route opens onto the church square. There stands a massive seventeenth century church, proud and imposing. Its pale stone walls dominate the space like an unmovable rock, while its bell tower, simple yet dignified, evokes the quiet strength of rural faith. |

|

|

| Soon, the itinerary leaves the village by Rue de Mérairie, where fine winegrowers’ houses still line the way, faithful remnants of a life rooted in the vine. At the village exit, a crossroads awaits the walker. The scallop shell, discreet messenger of pilgrimage, points unambiguously toward the road on the right, to be followed with confidence. |

|

|

| For some pilgrims, this will be the only moment of real exertion on the stage. Yet there is no need for concern. The climb remains gentle, never unforgiving. Like their wines, the Burgundian slopes know how to assert themselves without ever losing balance or grace. |

|

|

| Higher up, at a bend in the road, a cross rises like a spiritual pause along the way. Here, the cycle path, shared with the Way of Santiago, takes the road on the right and continues its ascent through the heart of the vineyards. The rows of vines seem to accompany the traveler upward, step by step. |

|

|

| Stone walls, enclosing and protecting the clos, grow more frequent and more imposing as elevation increases. They draw clear geometric lines across the landscape, a reminder that every meter of this vineyard is cherished ground, carefully and jealously defined. |

|

|

| Harvest season is still in full swing across the vineyards. Vehicles parked along the roads, trailers loaded with grape clusters, and the brisk movement of workers all bear witness to this intense seasonal rhythm |

|

|

| The road continues to climb gently, winding between the vine rows. At times, the walker’s pace aligns with that of passing cyclists, swift silhouettes sharing the effort of the climb and reminding us that this land belongs equally to contemplative slowness and sporting speed. |

|

|

| Then, from the crest of the hill, the small road finally tilts downward and begins its descent toward Volnay. The horizon opens, and the village appears as a promised resting place, nestled within the embrace of the vines. |

|

|

| Soon, the road enters Volnay via Rue de la Piture. The walker steps into a human scaled world, where every stone and every façade tells a story of labor, continuity, and transmission. |

|

|

| Volnay asserts itself as a quintessential winegrowers’ village. Solid houses built of pale stone, with powerful walls and dark roofs, express a rustic sobriety paired with discreet elegance. This architecture is deeply rooted in the land, inseparable from the vine that has sustained it. |

|

|

| The route then crosses the heart of the village toward the church. On sunny weekends, a nearby restaurant overflows with life. In its shaded garden, tables fill quickly, voices rise, and the air becomes scented with wine and shared meals. |

|

|

| The route circles the church, whose imposing silhouette continues to dominate the village center as both a spiritual and temporal landmark. |

|

|

| It then follows Rue de la Combe, a narrow street lined with fine winegrowers’ houses, pressed close together as if seeking protection from time itself. Soon, the scallop shell and the cycle path markings guide the walker left toward Rue de la Chapelle, and the pilgrim’s steps follow with quiet assurance. |

|

|

| The small road then leaves the houses behind, passes an old washhouse with moss covered stones, a witness to ancient gestures, and slopes gently through the vineyards. It leads toward the Chapel of Notre Dame de la Pitié, a modest spiritual sentinel set amid the green sea of vines. |

|

|

The chapel, flanked by its cemetery, is a fine sixteenth century structure. At this point, the route crosses the D973 departmental road and continues on the other side, as though closing one chapter before opening the next.

| Beyond the chapel, a road begins to descend before unfolding once again through the heart of the vineyard. Calm and open, it restores the full measure of Burgundian wine landscapes. |

|

|

| At a crossroads, doubt might briefly arise. Yet the scallop shell, carefully placed along the cycle path, clearly indicates the direction to follow, to the right. The pilgrim resumes a steady rhythm, reassured by this discreet but essential guidance. |

|

|

| From here, a long straight crossing unfolds. Nearly two kilometers without effort, flat and open, between perfectly aligned vines. Freed from the demands of the slope, the gaze lifts toward the horizon. In the distance, always receding, the slender bell tower of Meursault rises. Anticipation turns to desire, as the village seems to withdraw with every step forward. |

|

|

| To the left of the road, the departmental highway runs parallel, a broad ribbon of asphalt skirting the vineyards of the plain. The contrast is sharp between the measured, unhurried pace of the walker and the distant speed of passing vehicles. |

|

|

| Meursault stands apart through a fundamental distinction. Where Pommard and Volnay devote themselves to Pinot Noir and the expression of great red wines, Meursault celebrates Chardonnay. Here are born some of the world’s greatest white wines, luminous and full bodied, carrying within them the minerality of limestone soils and the gentle caress of the Burgundian sun. |

|

|

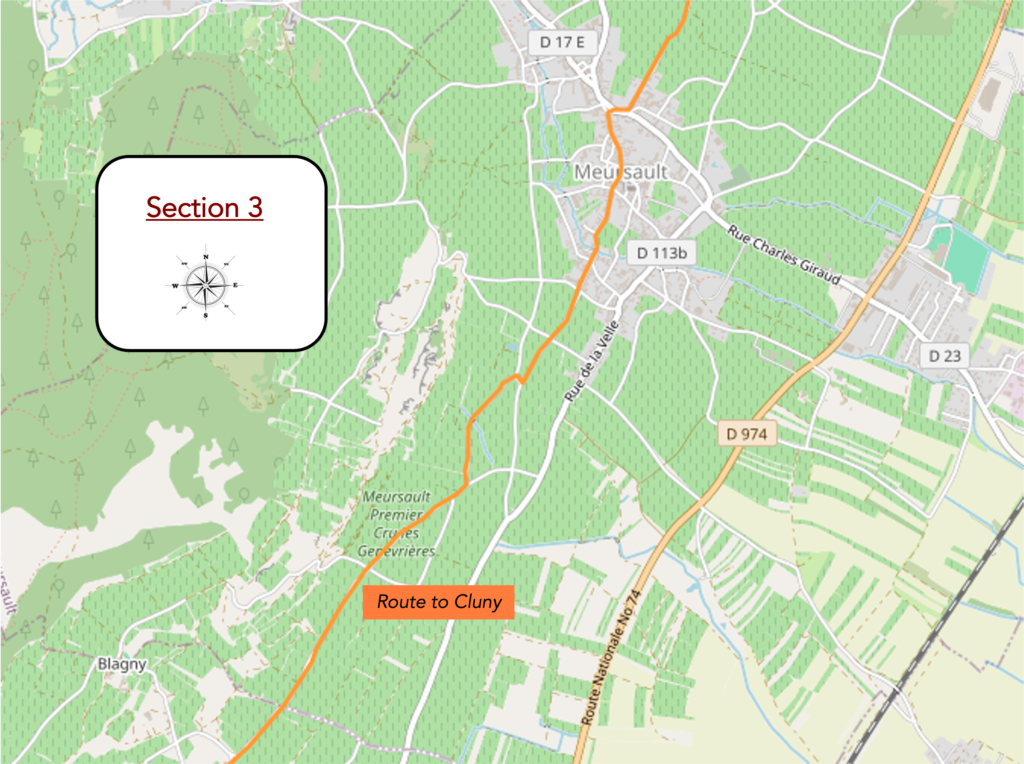

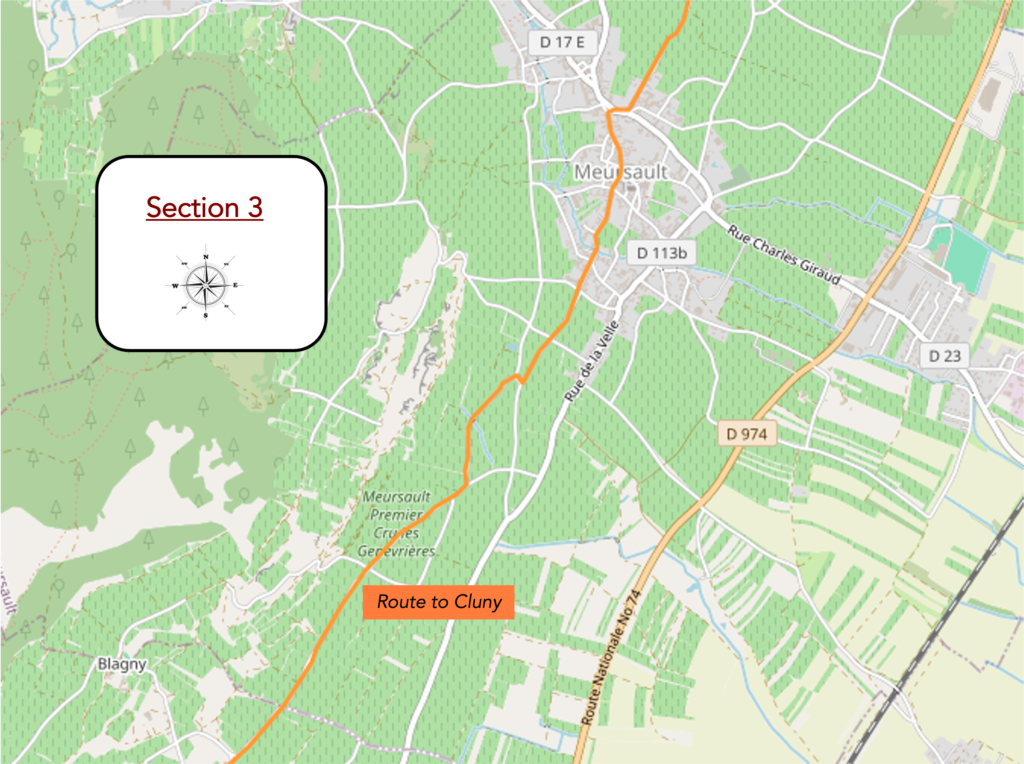

Section 3: In the white wines of Meursault and Puligny Montrachet

Overview of the route’s challenges: route without difficulty.

| Time passes here and stretches out like a long breath along this seemingly endless cycle path, perhaps a little too endless. The church bell tower, a slender promise standing in the distance, appears to retreat with every step forward, like a stubborn mirage slipping away beneath the walker’s feet. The road becomes an exercise in patience, and waiting itself turns into a form of travel. |

|

|

| Along the road, the eye is sometimes drawn to small dry-stone shelters, all alike like sisters, set down with their slanted roofs that make them resemble modest chapels. These rough refuges, exposed to the harshness of the elements, served winegrowers for centuries and still offer rest to weary walkers today. When rain falls with the force of an iron curtain, or when heat turns the air into an oven, they become precious havens, discreet protectors for anyone willing to sit on their simple stone bench. |

|

|

| Gradually, the cycle path draws closer to Meursault. Yet the approach is deceptive. From one bend to the next, one believes the goal is within reach, imagines already the cool shade of cellars or the scent of ancient stone, only to see another curve unfold, like a promise deferred. The road plays with the traveler’s hopes, inviting patience and putting it gently to the test. |

|

|

| And the dance of bends continues, tirelessly, again and again, as though the road had chosen to waltz rather than arrive. |

|

|

| At the entrance to Meursault, a vast wine estate suddenly rises, enclosed by high and imposing walls. The stone, silent and massive, seems intent on preserving a jealously guarded secret, that of wine and its slow, quiet alchemy. |

|

|

| The path then slips between the winegrowers’ houses lining the outskirts of the village. Their façades tell, to those who know how to read them, the story of generations of hands that pruned the vine, pressed the grapes, and watched patiently over the vats. |

|

|

| At last, it opens onto Place Gabriel Poupon, below the village, where majestic cellars, like stone cathedrals, welcome visitors and keep cool the liquid treasures of an age-old terroir.

Film lovers know Meursault through another lens, that of the silver screen. With a knowing smile, they recall certain scenes from La Grande Vadrouille by Gérard Oury, released in 1966, immortalized by the legendary duo Louis de Funès and Bourvil. A long sequence of the film is anchored in collective memory here. Yet cinema, master of illusion, was not always faithful to the location. Many scenes meant to take place in Meursault were in fact filmed in the Vézelay area. The outdoor night scenes, as well as shots showing signs marked “Meursault”, were shot elsewhere. Only the Meursault town hall, housed in a former fortified castle, truly served as a setting, transformed for the occasion into the Kommandantur in the film. |

|

|

| From here, the route sets off along Rue Pierre Joigneux, discreet and understated, before joining and climbing Rue du 11 Novembre. This artery crosses the lower part of the village, a guiding thread lined with splendid winegrowers’ residences built of pale stone, shaped with the elegance and rigor of past centuries. These solid and harmonious houses still carry on their façades the memory of the generations of vintners who lived there, between hard labor and celebrations of wine. |

|

|

| From there, continuing along Rue de Lattre de Tassigny, the walker reaches the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville. This is the vibrant heart of the village, where history, daily life, and the deep soul of Meursault converge. Arriving here gives the walker the feeling of finally touching the center, the very core of this small wine town, where every stone seems to resonate with an immemorial heritage. |

|

|

|

|

| Meursault is a village with an irresistibly touristic charm, a setting that appeals both to lovers of heritage and to admirers of the vine. At dawn, when the pale light stretches across the rooftops, the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville and the Church of St Nicolas reveal themselves in a suspended atmosphere, filled with calm and quiet majesty. The church, a venerable fifteenth century building, harmoniously blends Romanesque and Gothic styles, as if two eras were conversing through stone. The fortified castle of Meursault recalls the site’s defensive and seigneurial past. Built in the fourteenth century, it became the town hall in the nineteenth century. Its glazed Burgundian tile roofs, radiant with color, offer a characteristic polychromy emblematic of the region. |

|

|

| Near the town hall, the route follows Rue des Écoles. |

|

|

| This is a sloping street, gently descending on the far side of the village. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the Cloux unfolds, a charming stream flowing modestly beneath a stone bridge. |

|

|

| The route then continues straight ahead, first along “Rue des Clos de Mazeray”, then along “Rue du Pied de la Forêt”. Here, the road aligns with the cycle path, like two parallel lines moving together in a smooth and natural rhythm. |

|

|

| At the end of the street, the route turns right. A carefully placed scallop shell indicates the direction and marks the departure from Meursault, like a final wave before setting out once more into the heart of the vineyards. |

|

|

| Leaving the village, the road crosses a vast estate protected by high stone walls. These ramparts of silence enclose hectares of vines, guardians of a wine heritage whose secrets pass quietly from generation to generation. |

|

|

| Here, there is no risk of losing the way. The direction is easy to read, one simply follows the cycle path, a faithful companion. |

|

|

| Farther on, an intersection appears. The main road continues straight toward Puligny, but the route remains loyal to the cycle path, bending calmly to the right, following the scallop shells and the logic of pilgrimage. |

|

|

| The cycle path then makes a small curve, but the indication is clear and reassuring, reinforced once again by the scallop shell. Like a benevolent wink, it assures the walker that the way is correct. |

|

|

| In this beautiful vineyard, one sometimes encounters old signs, partially erased by time, indicating the presence of superior crus. Even half faded, these markings remain imprints of prestige, discreet witnesses to an exceptional terroir. |

|

|

| Then the road slopes up slightly, always gently and with restraint. Never here do the slopes impose harsh gradients. The road keeps its balance, as if intent on sparing the traveler’s breath. |

|

|

And if you take the time to turn around, the village of Meursault still appears, nestled within the folds of the vines. Its rooftops and bell tower stand out in the distance, reminding the walker where the journey began and offering one last image to carry away in memory.

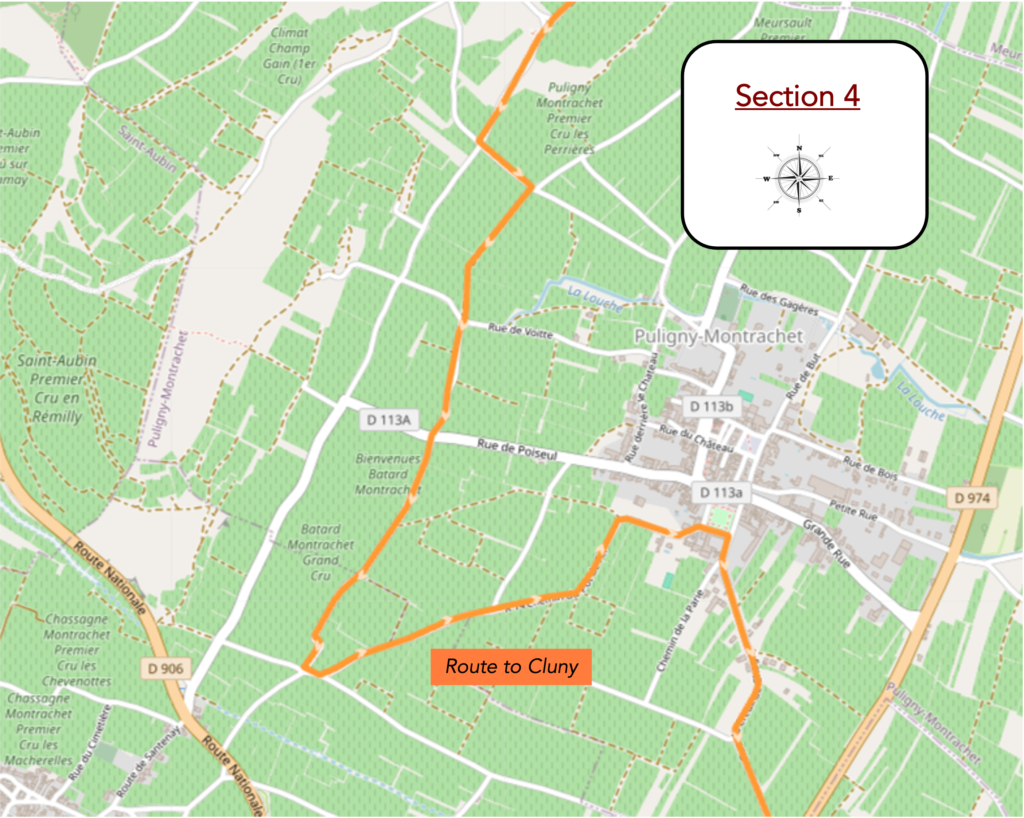

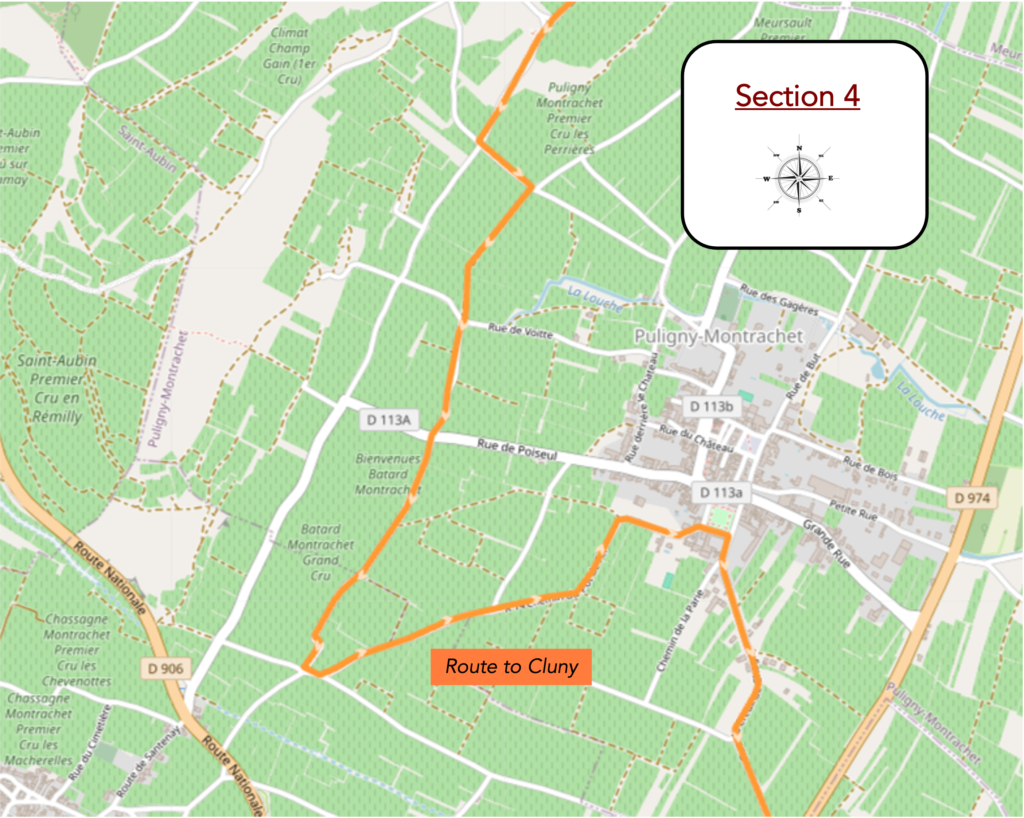

Section 4: Via the Puligny Montrachet variant

Overview of the route’s challenges: route without difficulty.

| Farther on, the cycle path aligns with a broader road, unrolling its ribbon in the direction of Santenay. |

|

|

| The vineyard remains unchanged, a silent companion to the walk. As far as the eye can see, the orderly rows of vines rise gently along the slope, like a disciplined vegetal army, each vine anchored in the soil with the patience of centuries. |

|

|

| Soon, at the turn of a glance, Puligny Montrachet emerges, its rooftops appearing amid the vines, resting on the plain like a jewel set within a green casket. |

|

|

| In this vineyard, you will encounter few walkers. The road belongs mostly to cyclists. Alone or riding in groups, they move forward with steady rhythm, sometimes assisted by a discreet motor, sometimes driven only by the strength of their legs. Many are enthusiasts, eager to test themselves on these gentle yet demanding roads, which they ride as you savor a glass of wine, with ardor and perseverance. |

|

|

| On the horizon, a small wooded area soon takes shape. Its mass of green announces a promise of coolness, like a wooded oasis in the middle of a sea of vines. |

|

|

| The road reaches it quickly. A bicycle park and picnic tables await travelers beneath the benevolent shade of the trees. This sheltered spot invites a pause, a moment to rest tired legs and enjoy a brief respite. |

|

|

| Then the road descends gently through the wooded area, winding beneath the canopy of trunks, as though it wished to prolong the calm of this refuge before returning to the clarity of the hillsides. |

|

|

It finally opens onto a crossroads. A choice presents itself here. Continuing straight ahead leads toward Chassagne Montrachet. This route goes farther still, reaching Rémigny before arriving at Chagny, but it is a very long detour. The kinder alternative is to follow the Puligny Montrachet variant, also marked with scallop shells. The pilgrim hesitates. Is one an unconditional lover of vineyards, ready to extend the effort, or does one prefer to spare legs and breath. There is good reason in this choice, as the variant allows a direct return to Chagny, saving more than five kilometers.

| By following the variant, the route sets off on a gentle descent toward Puligny, accompanied by the cycle path. One scallop shell, poorly oriented, seems intent on confusing the traveler, but a well-placed arrow restores the correct direction, like an invisible hand guiding each step. |

|

|

| The road then stretches into a long and elegant curve, like a ribbon laid out between the vines, before finally reaching the village. The eye is drawn along this fluid line, which follows the contours of the land and quietly invites patience. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the road opens onto Puligny Montrachet, a discreet jewel nestled at the heart of the vines. The traveler enters it as one crosses the threshold of a precious estate, still wrapped in silence and promise. |

|

|

| At the entrance to the village, on a small hill, a picnic area has been laid out. A true oasis of rest, it offers tables and light shade, inviting the pilgrim to catch their breath before continuing the discovery. |

|

|

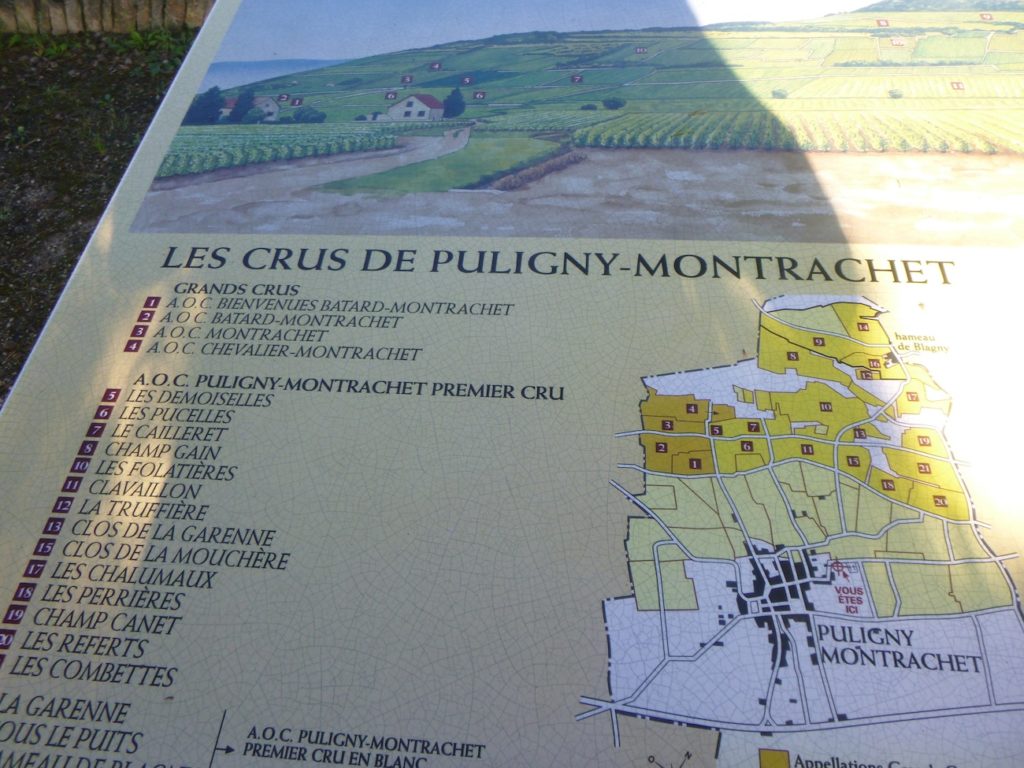

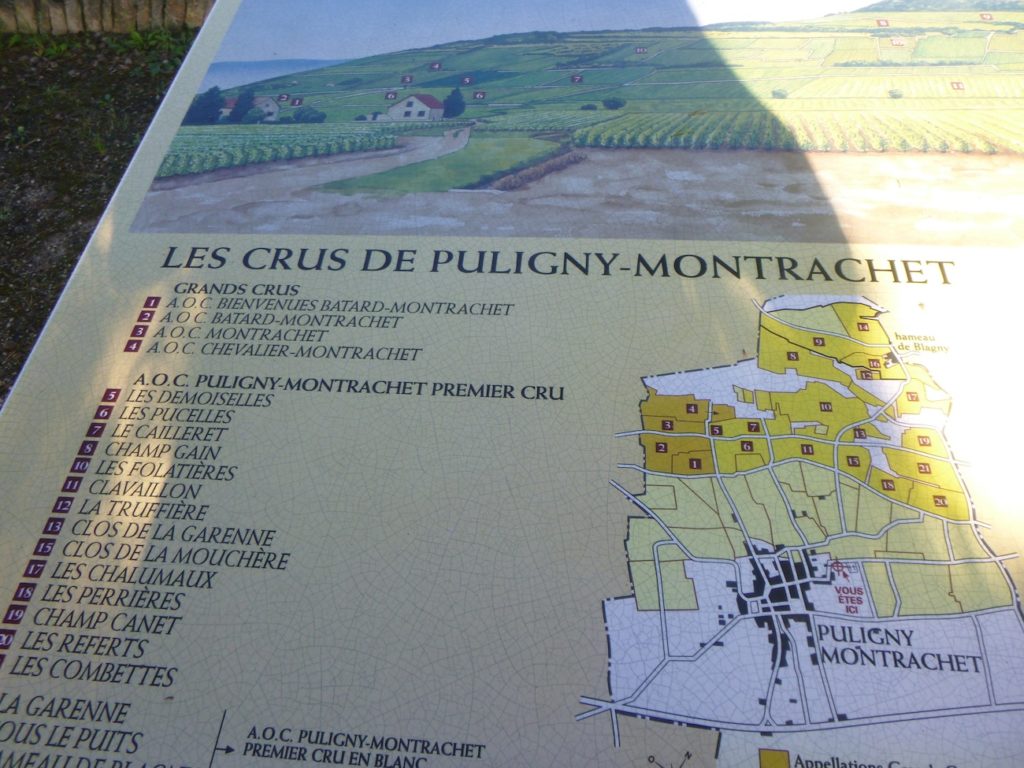

An information panel carefully details the wine treasures held by this village. Almost exclusively white wines made from Chardonnay, the reigning grape of these luminous slopes. The first names mentioned are those of the communal AOC crus, whose richness unfolds into a constellation of Premier Crus, each carrying its own nuance, its own vibration of this unique terroir. Yet Puligny enjoys an even rarer privilege. It is home to five exceptional Grands Crus, all united under the prestigious banner of Montrachet. Among them are the almost unattainable Montrachet itself, the powerful Bâtard Montrachet, and the noble Chevalier Montrachet, whose names resonate like chivalric titles inherited from another age. These extraordinary nectars, born of centuries old expertise and soils seemingly blessed by the gods, reach prices that inspire vertigo. It is not uncommon to see bottles exchanged for around one thousand euros, while the greatest vintages, destined for majestic aging, climb even higher, ten, fifteen, sometimes twenty thousand euros for a few drops of eternity. To your good health, for here raising a glass is a salute to history, to the land, and to the art of wine at its highest expression.

| “Climats”, as vineyard parcels are known in Burgundy, are matters of singular terroirs, almost mysteries buried within the soil. When one looks up toward the rows of vines, it is difficult to understand why the Montrachet wines are concentrated on this tiny slope, while just a few meters away, other appellations, equally cared for by winegrowers’ hands, remain more discreet and less celebrated. To the naked eye, nothing distinguishes a so-called exceptional vineyard from another, and yet reputation, nobility, and value are decided here, in the invisible depth of ancient soils, within layers of limestone, clay, and marl. Everything depends on the subsoil, on what lies silently beneath the vines, nourishing drop by drop the precious berries. |

|

|

| The variant then enters the heart of the village, as if to reveal its soul. At the entrance, a statue pays tribute to winegrowers, those artisans of patience and time, standing beside an imposing wine cellar, a true temple devoted to wine. |

|

|

| Here, the route is not marked. Left to their own devices, the walker might hesitate. Yet there is no cause for concern. The route can be read, and we will guide you. One simply crosses the small park, peaceful like a pause outside of time, where the shade of trees seems to accompany the steps of modern pilgrims. |

|

|

You then find “Rue du Creux de Chagny”. It is essential to identify this discreet, almost secret street, at the far-right edge of the park, for it is the key to continuing the itinerary without losing the way.

| This tree lined street slips quietly out of the village, as though offering the walker a gentle transition back toward the vines. Along the way, you will encounter a crossed-out sign, strange and disconcerting, seemingly indicating that you are no longer on the correct route. What nonsense. It is yet another oddity born of the way marked paths are managed in the region. Rest assured, this street is indeed part of the route, and there is no reason to hesitate. |

|

|

| The street stretches on at length, yet offers a pleasant sense of calm. Steps fall into a steady, almost meditative rhythm, as though the monotony of this straight line itself had become restful. . |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, the landscape opens once more, and the vineyard reclaims its place, a faithful companion along the road, unfolding its aligned vines like a patient army facing time. |

|

|

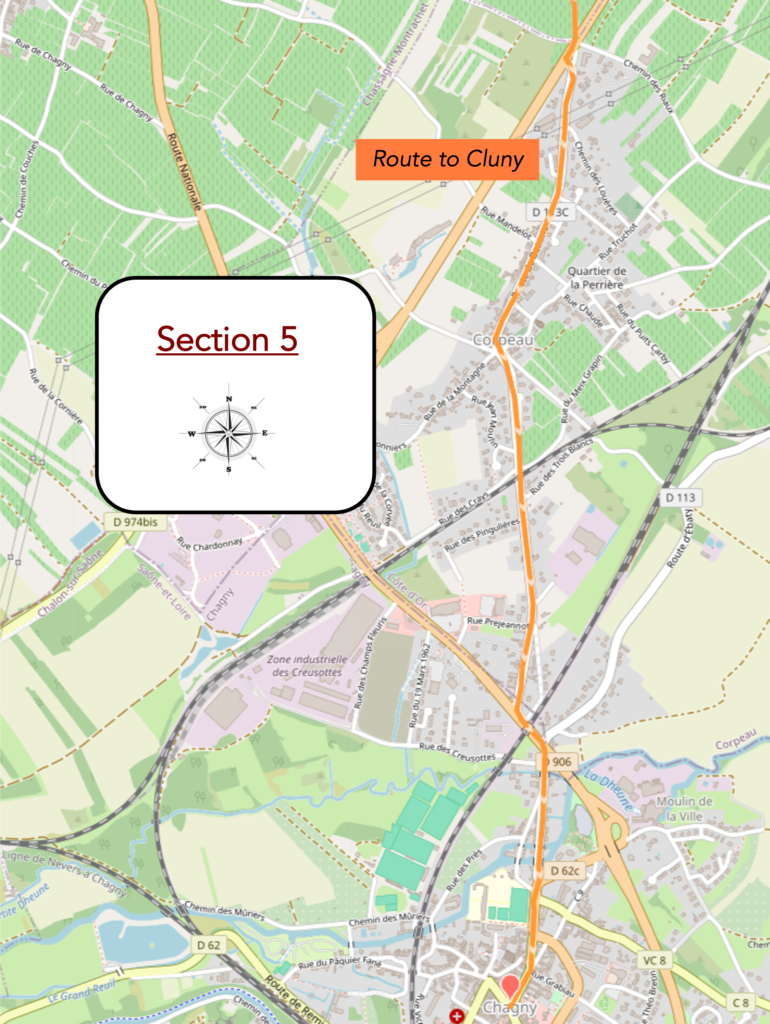

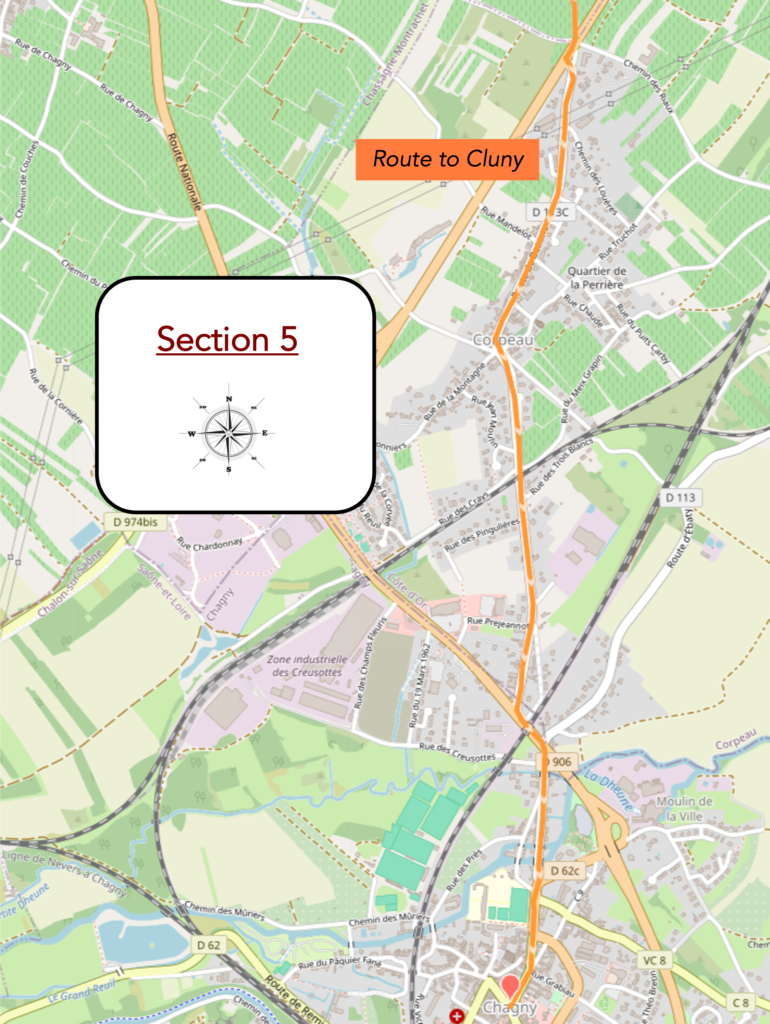

Section 5: Away from the vineyard

Overview of the route’s challenges: route without difficulty.

| Very quickly, the road joins the major departmental road D974, a vital artery linking countless villages and crossing Burgundy like a taut thread stretched across the land. |

|

|

| This is also the land of the St Vincent Tournante, a unique wine festival held each year on the last weekend of January. Its principle is both simple and magnificent. One appellation invites the others to celebrate, and for the occasion, villages dress themselves in countless decorations while stalls spring up, offering visitors the chance to taste the wines. It is a joyful and almost sacred communion around the Burgundian nectar. Saint Vincent, patron saint of winegrowers, is honored in this shared celebration, like an annual blessing recalling the deep bond between the vine, those who work it, and those who celebrate it. |

|

|

| Here, you leave the vineyards behind and enter Corpeau by following the departmental road D113c. The landscape changes abruptly. The strict geometry of vine rows gives way to the first houses, and the approach of the town can already be felt. |

|

|

| Corpeau feels like a broad suburb of Chagny. The route stretches on through shaded avenues lined with benevolent trees, running past peaceful villas with carefully tended gardens. The walker’s pace becomes steadier, almost urban, though the greenery still preserves a trace of the hillside spirit. |

|

|

| The village extends lengthwise, unrolling like a ribbon until it reaches the heart of its old center. |

|

|

| At its core, there is no bustling commerce. Life moves more quietly here. Yet a well frequented wine cellar reminds visitors that even in this calm, wine remains the community’s guiding thread. The road passes close to a modest church, sober and unadorned. |

|

|

| Leaving this older and more inhabited section, the route follows the Route de Beaune. |

|

|

| Along this road, which slopes gently down toward newer housing developments, you encounter a reassuring sign of the Way of Santiago, a reminder that you are still walking a pilgrimage route, humble yet rich in symbolism. |

|

|

| Farther on, the road crosses the railway line, a metallic trace cutting straight through the landscape. Here, you leave the Côte d’Or and enter Saône et Loire. |

|

|

| The itinerary then continues in a long, straight line along a tree lined sidewalk, passing through modern residential neighborhoods. The walk is steady and perhaps monotonous, yet it quietly prepares the mind for the approaching arrival. |

|

|

| At last, you leave this long crossing of Corpeau behind. The road once again passes beneath the railway, as if marking the threshold of a new territory. . |

|

|

| You are now on the departmental road D906. The route crosses this major road at the entrance to Chagny, the final approach before the end of the stage. |

|

|

| At the entrance to the town, the road crosses the Dheune, a small river whose often murky waters slip at times into tangles of shrubs and willows bending over its bed. . |

|

|

| Ahead stretches a long straight boulevard lined with trees, where the road, your faithful companion, crosses the river once more, as if offering a final farewell. The water flows lazily, indifferent to the passage of walkers and cars alike, yet always present, like the city’s quiet, subterranean breath. |

|

|

| A little farther on rises the familiar and understated silhouette of the church. Its bell tower, without ostentation yet firm in presence, dominates the surrounding neighborhood. |

|

|

| The route finally leads you into the beating heart of Chagny, home to some 5,400 inhabitants, entering the town center via Rue de Beaune. Here, the urban soul reveals itself, where passersby, shops, and memories intersect in a Burgundian town of human scale. |

|

|

| Chagny’s town hall is a fine late nineteenth century building, flanked by two wings that house covered market halls where markets are held on Thursdays and Sundays. The Sunday market, well known and highly popular, spreads across the entire town center. |

|

|

Chagny is also home to Lameloise, where the creative chef Lameloise handed over the keys to Éric Pras in 2009. Housed in a former coaching inn in the heart of Burgundy, the establishment welcomes guests into a setting where Michelin stars and a four-star hotel flourish. These, of course, are not prices suited to the purse of the average pilgrim.

Official accommodations in Burgundy/Franche-Comté

- Domaine Violot, 7 Rue Ste Marguerite, Pommard; 03 80 22 49 98; Guestroom

- Hôtel-restaurant du Pont, Rue Monge, Pommard; 03 80 22 03 41; H0tel

- Camping La Grappe d’Or, 2 Route de Volnay, Meursault; 03 80 21 22 48; Camping

- Gîte d’étape la Velle, 17 Rue Velle, Meursault ; 03 80 21 22 83/06 11 83 89 69; Gîte

- Gîte Le Clos d’Isandor, 5 Route de Monthélie, Meursault; 03 80 21 60 58; Gîte

- Les Écureuils, 20 Rue Pierre Joigneaux, Meursault; 03 80 21 27 82/06 78 02 82 81; Guestroom

- La Maison de Charme, 22 Rue Mazeray, Meursault; 03 80 24 31 69; Guestroom

- Hôtel Le Globe, 17 Rue de Lattre de Tassigny, Meursault; 03 80 21 64 90; Hoel

- Le Paquier Fané, Chagny; 03 85 87 21 42/06 18 27 21 99 ; Camping

- Hôtel de la Poste, 17 Rue de la Poste, Chagny; 03 85 87 64 40; Hotel

- Hôtel de la Ferté, 11 Boulevard de la Liberté, Chagny; 03 85 87 04 97; Hotel

Jacquaire accommodations (see introduction)

Airbnb

- Pommard (15)

- Volnay (3)

- Meursault (11)

- Puligny-Montrachet (9)

- Chagny (14)

Each year, the route changes. Some accommodations disappear; others appear. It is therefore impossible to create a definitive list. This list includes only lodgings located on the route itself or within one kilometre of it. For more detailed information, the guide Chemins de Compostelle en Rhône-Alpes, published by the Association of the Friends of Compostela, remains the reference. It also contains useful addresses for bars, restaurants, and bakeries along the way. On this stage, there should not be major difficulties finding a place to stay. It must be said: the region is not touristy. It offers other kinds of richness, but not abundant infrastructure. Today, Airbnb has become a new tourism reference that we cannot ignore. It has become the most important source of accommodations in all regions, even in those with limited tourist infrastructure. As you know, the addresses are not directly available. It is always strongly recommended to book in advance. Finding a bed at the last minute is sometimes a stroke of luck; better not rely on that every day. When making reservations, ask about available meals or breakfast options.

Feel free to leave comments. That is often how one climbs the Google rankings, and how more pilgrims will gain access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 17: Chagny to Givry |

|

|

Back to menu |