Along the ridges and through the dense forests of the Lower Jura

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-labbaye-dacey-au-mont-roland-dole-par-le-chemin-de-compostelle-80455784

| This is obviously not the case for all pilgrims, who may not feel comfortable reading GPS tracks and routes on a mobile phone, and there are still many places without an Internet connection. For this reason, you can find on Amazon a book that covers this route.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page. |

|

Today, the route makes a brief incursion into the Lower Jura. This region has nothing in common with the Upper Jura and its steep mountains near Switzerland. Here, everything is calmer, more secretive. The Lower Jura seeks neither brilliance nor spectacle; it reveals itself slowly, like a confidence. The mountain gradually fades, becoming gentler, like an animal at rest. Its last foothills unfold into rounded hills, wooded shoulders, and low ridges guarded by beeches and hornbeams, long-standing and discreet companions of these landscapes. At the bend of the paths, villages built of pale stone emerge, dominated by their Franche-Comté bell towers. Farther on, beneath the silhouette of Mont Roland, Dole comes into view, the former capital of Franche-Comté resting along the Doubs River, like a jewel set in the valley.

The Lower Jura is neither entirely plain nor fully mountain. It is a land in between, a discreet crossroads where nearby Burgundy meets the first folds of the Jura. Here, horizons open wide, offering endless undulations of landscape. Yet despite this broad breathing space, a sense of intimacy remains, as if every path, every stone cross, every chapel wished to share its own secret. A land of passage and memory, the Lower Jura bears the imprint of pilgrims and farmers, and continues to offer those who walk its silence and open horizons.

Mont Roland, in this setting, is neither an imposing nor a fierce mountain. It is a sanctuary hill, a natural belvedere, a gentle elevation of the Lower Jura, rising above the plain like a hand extended toward the sky. From afar, its bell tower can be seen, a familiar silhouette watching over the villages and accompanying the steps of pilgrims. For centuries, it has drawn Compostela walkers, who find here a place of rest and reflection. The scallop shells carved into stone and the crosses planted at the bends of the paths bear witness to this centuries-old devotion. Around the monastery, trails wind beneath the trees, lined with statues, stone crosses, and small shrines that mark the walk like so many stations of an inner pilgrimage. Among them, the Black Madonna, mysterious and moving in her wooden form, gathers silent prayers. She embodies this blend of fervor, mystery, and simplicity that makes Mont Roland not only a place of passage, but a place of presence.

How do pilgrims plan their route? Some imagine that it is enough to follow the waymarking. You will discover, often to your cost, that the waymarking is frequently deficient. Others rely on guides available on the internet, which are also often too basic. Others prefer GPS, provided they have imported the Compostela maps of the region onto their phone. Using this method, if you are skilled in GPS use, you will not get lost, even if the route proposed is sometimes not exactly the same as the one indicated by the scallop shells. You will nevertheless arrive safely at the end of the stage. In this regard, the site considered official is the European route of the Ways of Compostela (https://camino-europe.eu/). For today’s stage, the map is accurate, but this is not always the case. With a GPS, it is even safer to use the Wikiloc maps that we make available, which describe the current waymarked route. However, not all pilgrims are experts in this type of walking, which for them distorts the spirit of the path. You can therefore simply follow us and read along. Every junction on the route that is difficult to interpret has been indicated, to help you avoid getting lost.

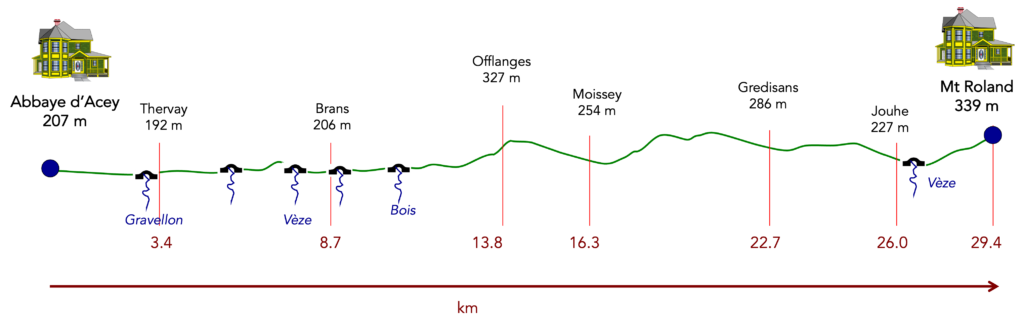

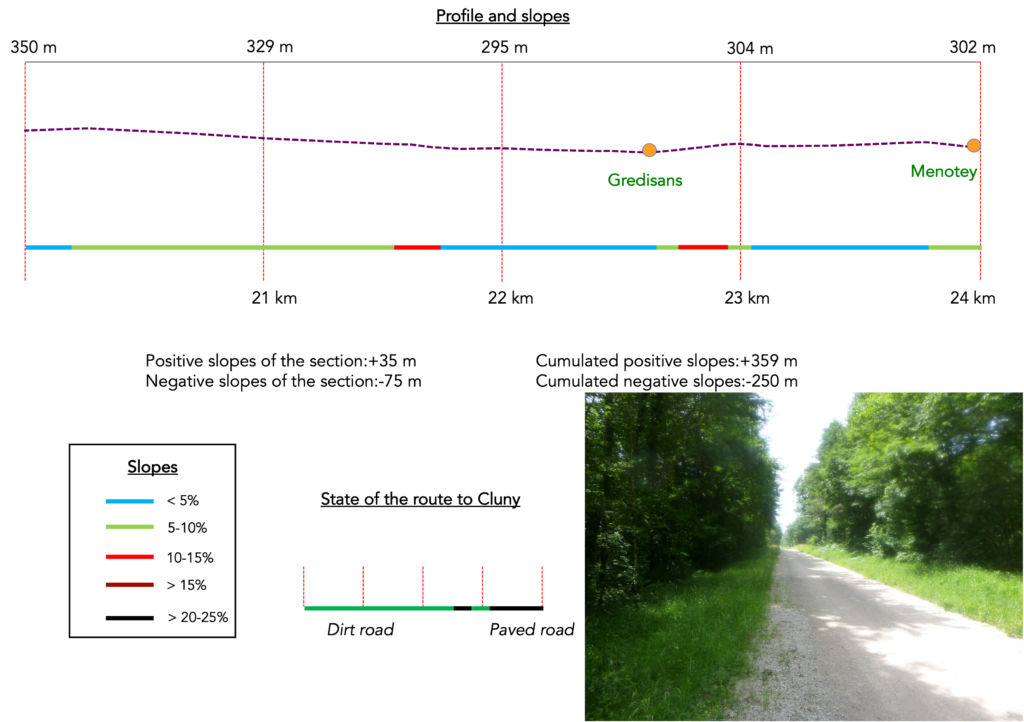

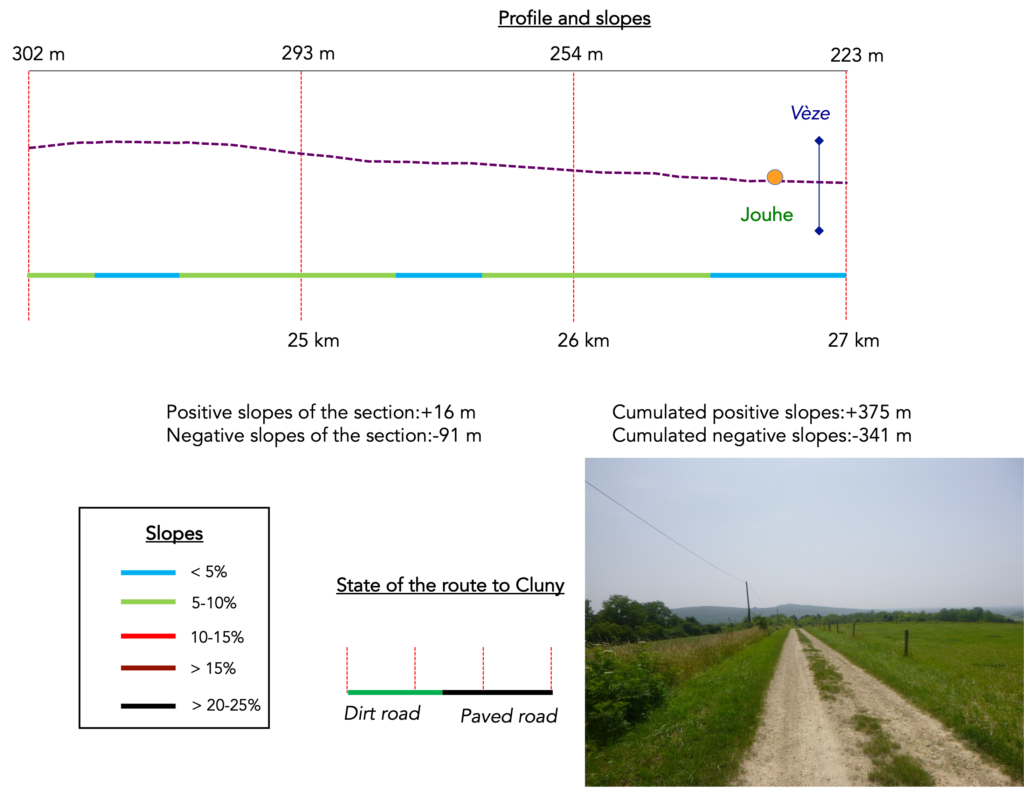

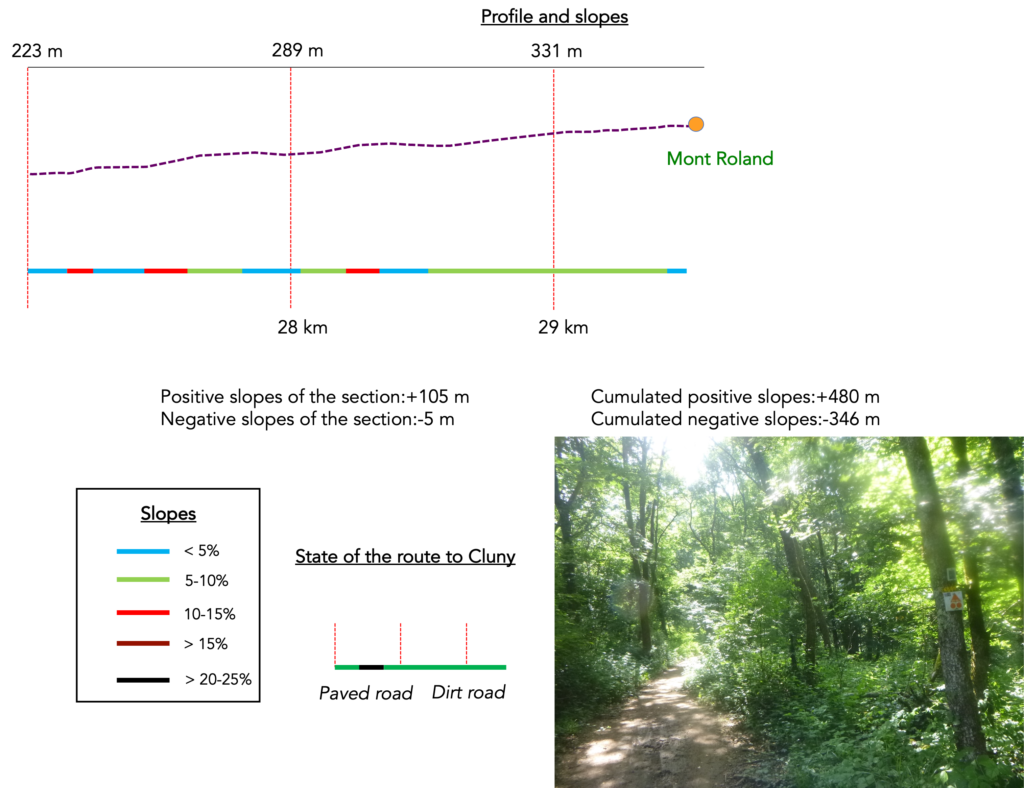

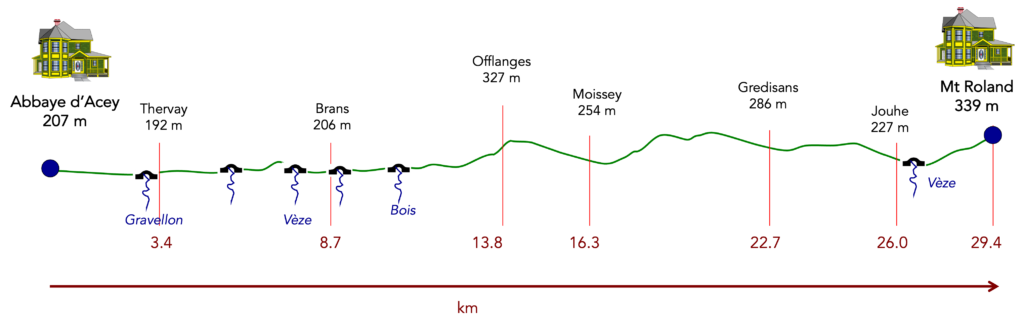

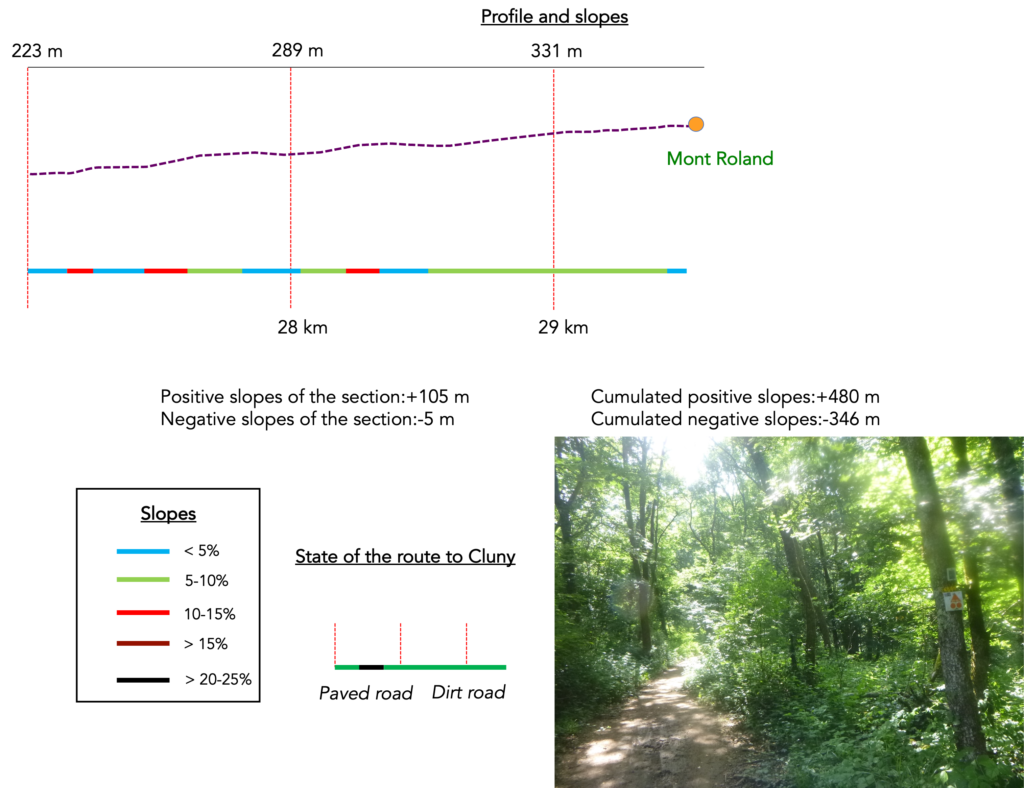

Difficulty level: The journey is not without difficulty, although the elevation changes (+480 meters/ -346 meters), remain fairly reasonable for a very long stage. Three serious climbs characterize the route. The most demanding is on the hill of Offlanges, but the ascent toward Gredisans and the climb up to Mont Roland will also require a few drops of sweat.

State of the route: Today’s stage includes slightly more paths than roads:

- Paved roads: 13.7 km

- Dirt roads: 15.7 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

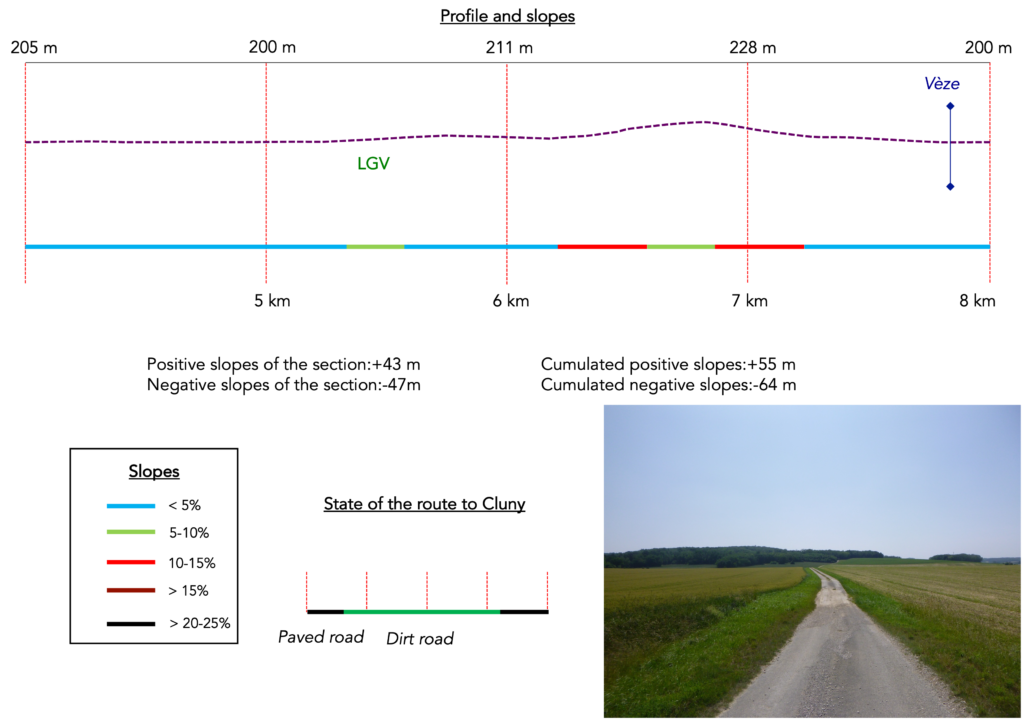

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

Section 1: Along the Oignon River, seldom seen

Overview of the route’s challenges: a route with no particular difficulty.

| The route leaves the abbey by descending the road. The gaze turns back for a moment toward the age-old walls, as if to carry away one last fragment of silence. The air still seems inhabited by the murmur of the offices, but already the stone fades behind the trees, and the route toward the horizon begins. |

|

|

| The road slopes gently downward, like a ribbon of grey flowing between meadows and cornfields. On either side, tall ash trees and sturdy oaks alternate with a few maples, familiar companions of this land of Franche-Comté. They watch over the walker like motionless figures, silent guardians of the passage. |

|

|

| The descent ends at an intersection. Another road cuts across it at a right angle, and the scallop shell, discreetly placed on a post, indicates the direction of Brésilley. This is where you turn right, and already the trace of the pilgrimage takes shape. |

|

|

| But the itinerary does not allow itself to be confined by the logic of modern roads. After a short while following this ribbon toward Brésilley, it suddenly branches off, almost capriciously. Here, once again, caution is needed with the scallop shells, which can sometimes mislead. It is not their orientation that guides the walker, but the associated arrow. Thus, it is to the left that the route opens, drawing the walker toward another landscape. |

|

|

| At first, the road still keeps a few trees along its edges. Their scattered foliage softens the light and tempers the severity of the sky. But this protection is short-lived. |

|

|

| Very quickly, the plain unfolds in all its nakedness. No more shade, no more boundary, only meadows and cornfields stretching as far as the eye can see beneath an immense sky. The walker becomes tiny, a silhouette moving through the monotonous infinity of cultivated land. |

|

|

| This is a vulnerable land, where the road itself knows how fragile it is. It runs alongside the Oignon, a capricious river whose floods overflow without effort. In times of heavy rain, water covers the roadway and makes it impassable. A few openings in the hedges, like windows cut into the green, sometimes allow a glimpse of the Oignon as it glides by, discreet or furious depending on the season. |

|

|

| Then the road moves away from the river, and with it disappears the rare shade of trees. The sun once again reigns alone. In this bare plain, the road runs straight, stubborn, as if it were aligned with a single star, the bell tower of the church of Thervay, visible in the distance as a slender line rising toward the sky. From now on, it is the horizon itself that draws the walk forward. |

|

|

| At last, after this long crossing, the first houses of Thervay appear, modest and discreet, hidden behind their foliage. The road seems, as if relieved, to take refuge in this fold of humanity. |

|

|

You find yourself once again beside the Oignon. Here, people have chosen to restore a spawning ground, so that the river may recover its memory of fertility. In its clear waters, fish come to lay their eggs, perpetuating an immemorial cycle, fragile yet vital.

| The road turns right, ignoring the cycle path and this time remaining faithful to the scallop shell. It crosses a small wood whose dense shade suddenly cools the walker’s step. |

|

|

| Then the road opens once more, leaving the protective cover of the wood to head toward the village. The houses draw closer, promising a pause. |

|

|

| At the entrance to Thervay, the discreet Gravellon stream murmurs softly, like a prelude to rest. |

|

|

| A picnic area welcomes the walker. Beneath tall trees, heavy benches of rough granite invite one to sit down. Their rugged stone holds the memory of time. Here, one can enjoy the cool air, set down a pack, before the road sets off again, turning left to enter the heart of the village. |

|

|

| The road then slopes up toward the church of St Martin. The building as it appears today dates in part from the seventeenth century. The centuries have laid down their layers here, giving the stones a relief shaped by history and devotion. |

|

|

On the square, a monumental fountain stands out. Its broad stone basin shelters three cast-iron swans, elegant despite their frozen stillness. Built at the beginning of the nineteenth century, it is listed in the Inventory of Historic Monuments. It bears witness to a time when water was not only a resource, but also a display, an adornment of the village. Not far from here once stood the château of Balançon, now in ruins. In the Middle Ages, it was one of the most powerful castles in Burgundy, but the route does not lead you there. All that remains is the breath of a prestigious past, which continues to haunt the surroundings.

| Leaving the village, the road gradually runs alongside a small oratory dedicated to Ste Philomena. Modest and almost unnoticed, it is nonetheless a sign, a reminder that here, every crossroads and every stone bears the mark of faith. |

|

|

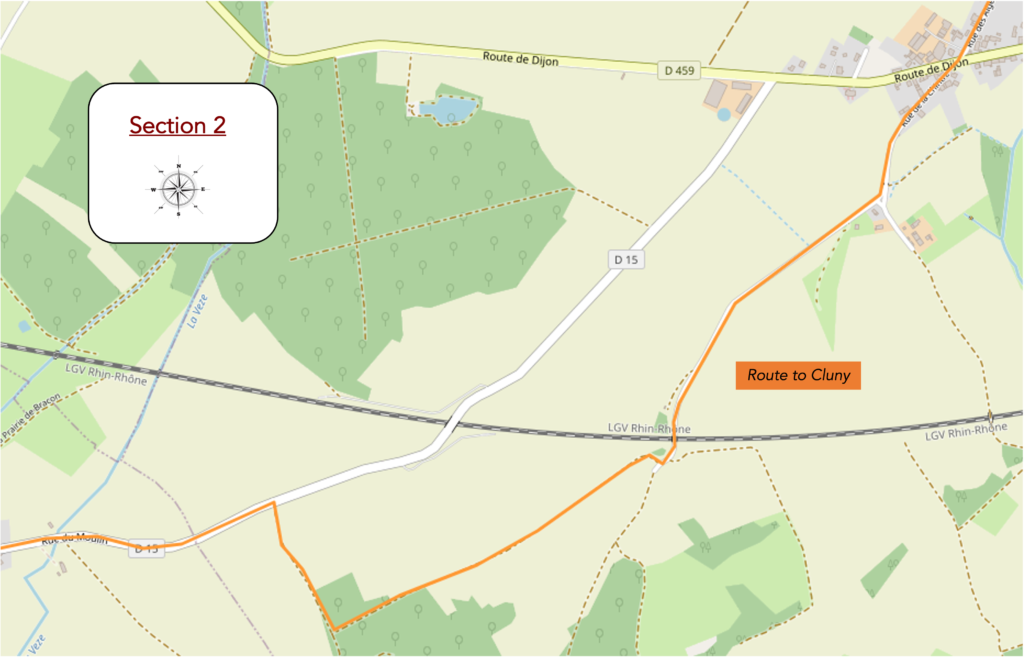

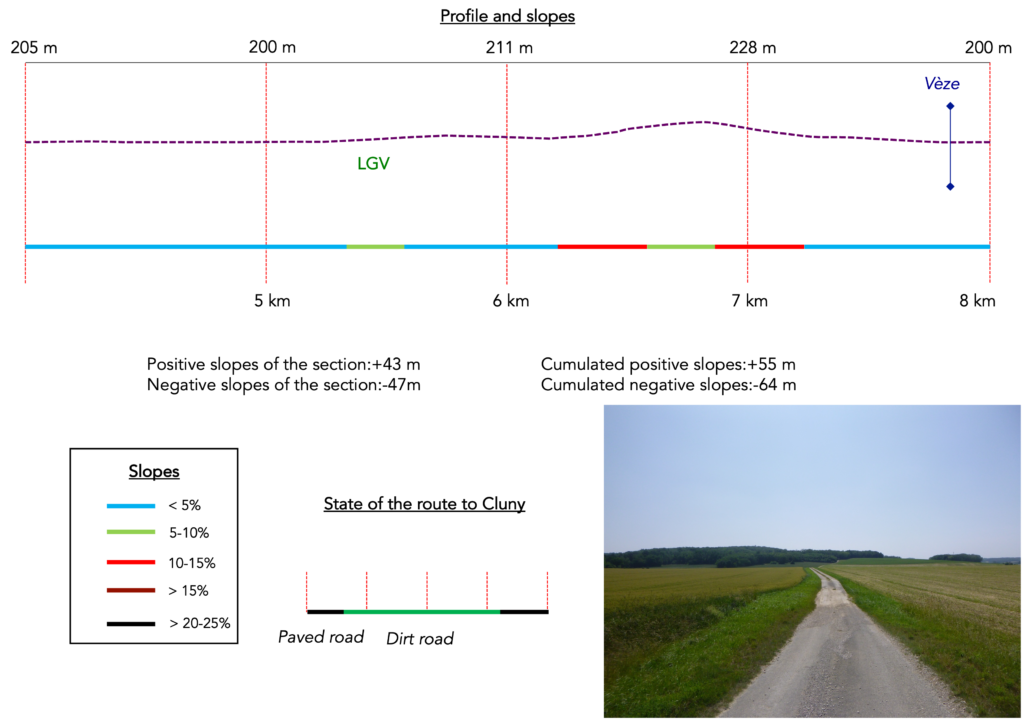

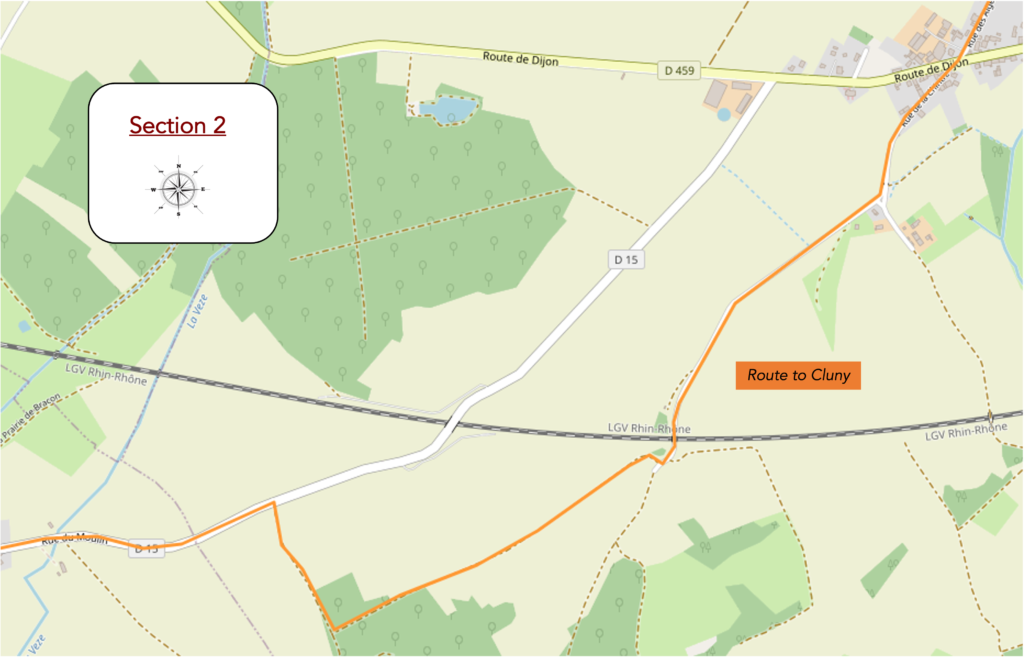

Section 2: Meeting the train again

Overview of the route’s challenges: a route with no particular difficulty.

| Shortly afterward, the road reaches a crossroads. There, in the middle of intersecting roads, stands an isolated house, a silent witness to this meeting of ways. The scallop shell, faithful companion of the walker, invites you to continue to the right, skirting this solitary building that seems to guard the passage. |

|

|

| You now find yourself once again on a dirt path, a long pale ribbon unfolding through the bare countryside. Not a tree breaks the line of the horizon, only the vastness of the plain, where the wind delights in running freely. It is a return to nakedness, to the purity of a landscape without ornament. |

|

|

| Far away from the path, a massive farm stands like an agricultural fortress. It dominates hundreds of hectares of meadows, maize, and cereal crops, land disciplined by the hand of man. Here, the fields seem to ignore oilseed crops. The region favors more traditional cultivation, the familiar silhouettes of wheat and maize forming monotonous checkerboards. |

|

|

| Already, in the distance, a small rise takes shape. It discreetly yet unmistakably signals the passage of the train, like a reminder that beneath this seemingly immutable landscape, modern speed is at work. |

|

|

| The route becomes monotonous. Long and drawn out, it puts patience to the test. Every ten minutes, the plain is cut through by the flash of a high-speed train. You hear it coming from far away, like a swelling murmur, before its roar tears through the air and vanishes at once. This brutal contrast between the stillness of the walker and the speed of the train gives the pilgrimage a strange intensity. |

|

|

| At the top of the rise, the path crosses the high-speed line. The bridge, massive and impersonal, spreads wide. It is always striking to see how much space this colossal infrastructure requires, simply to allow a succession of trains to pass like lightning. |

|

|

| At the exit of the bridge, you must once again let yourself be guided not by the scallop shell, still poorly oriented, but by the arrow that accompanies it. It is the arrow that indicates the direction to take, toward the right. |

|

|

| And it is a return to the dirt path. Almost endless and nearly straight, it unfolds its unyielding austerity. Here, the pilgrim has no choice but to let thoughts roll along like pebbles beneath each step. No shade, no refuge, only harsh light and cultivated land, meadows, maize, cereals, all repeating endlessly. In the distance, a small wood takes shape like a promise. |

|

|

| In this corner of the plain, cereals, especially wheat, become slightly more prevalent. |

|

|

Meanwhile, out on the plain, the train continues its course, unperturbed. A destiny fully mapped out, indifferent to the slowness of the walker who watches it fade away.

| Eventually, the stony path rises gently, gaining a little elevation. The small wood draws closer, like a long-awaited haven. |

|

|

| The walker then enters the shade of the wood. Here, everything feels familiar, an abundance of beeches and hornbeams intertwined, punctuated by solid oaks and ash trees, with a few scattered maples. It is a symphony of trunks and foliage, a world more humid and more secret. |

|

|

| But the ground does not soften. The path, strewn with sharp fragments of limestone, becomes rougher. It turns at a right angle and launches into a descent toward the plain. And in the distance, always, the persistent rumble of the train continues. |

|

|

| To the walker’s left, the village of Brans appears, set into the landscape like a discreet halt, almost motionless beneath its cloak of rural silence. |

|

|

| A little farther on, a large telecommunications mast pierces the sky. Immense and metallic, it seems to touch the clouds, as if conversing with the winds. It clashes with the countryside, yet it also speaks of the modern age watching over even these ancient paths. |

|

|

| The descent, now steeper, continues. At the bottom, the path meets the departmental road D15. Once again, the scallop shell and its arrow guide the step, and you must turn left. |

|

|

| The road then sets off, at first straight as an arrow, then more supple and winding. It undulates across the plain, bordered by meadows and cultivated fields. The landscape unfolds in its simple immensity, yet each bend holds the promise of a new detail, a moment of breathing space. |

|

|

| Little by little, the road draws closer to the village of Brans. Along the way, it crosses the Vèze, a small discreet stream that threads through the countryside with its calm waters. It flows quietly, yet it irrigates the landscape with a gentle humility. |

|

|

| As the village approaches, the meadows come to life. Livestock, peaceful and unhurried, stand in the fields. Their slow, solid silhouettes, moving patches of green, accompany the walker with their benevolent presence. |

|

|

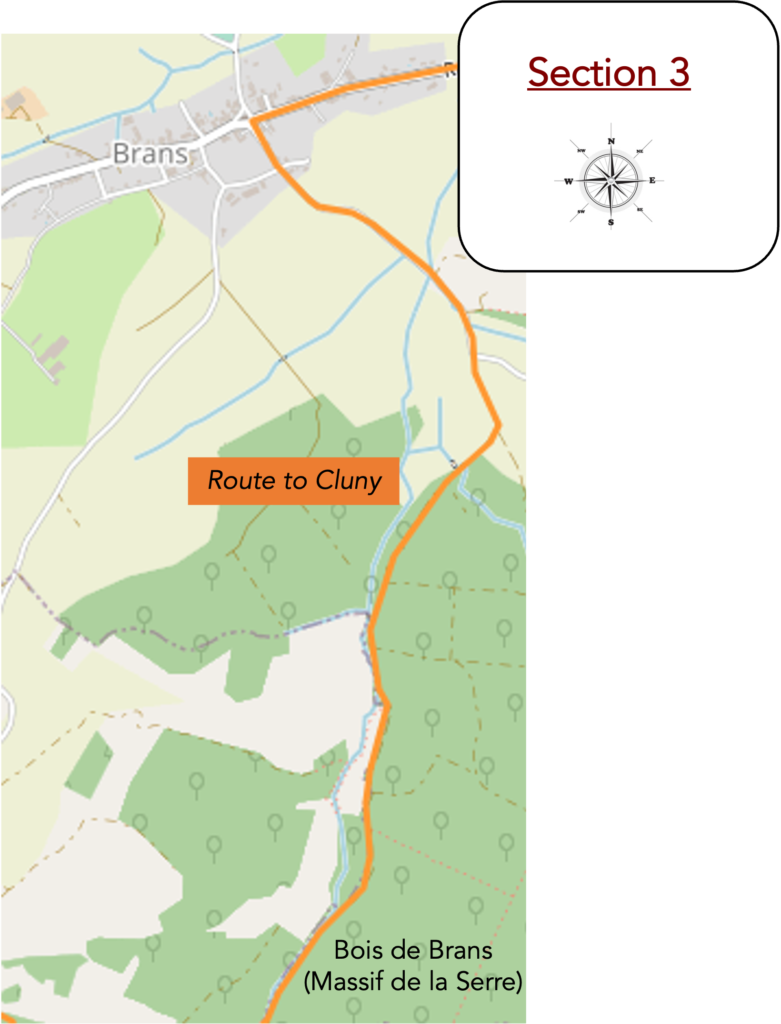

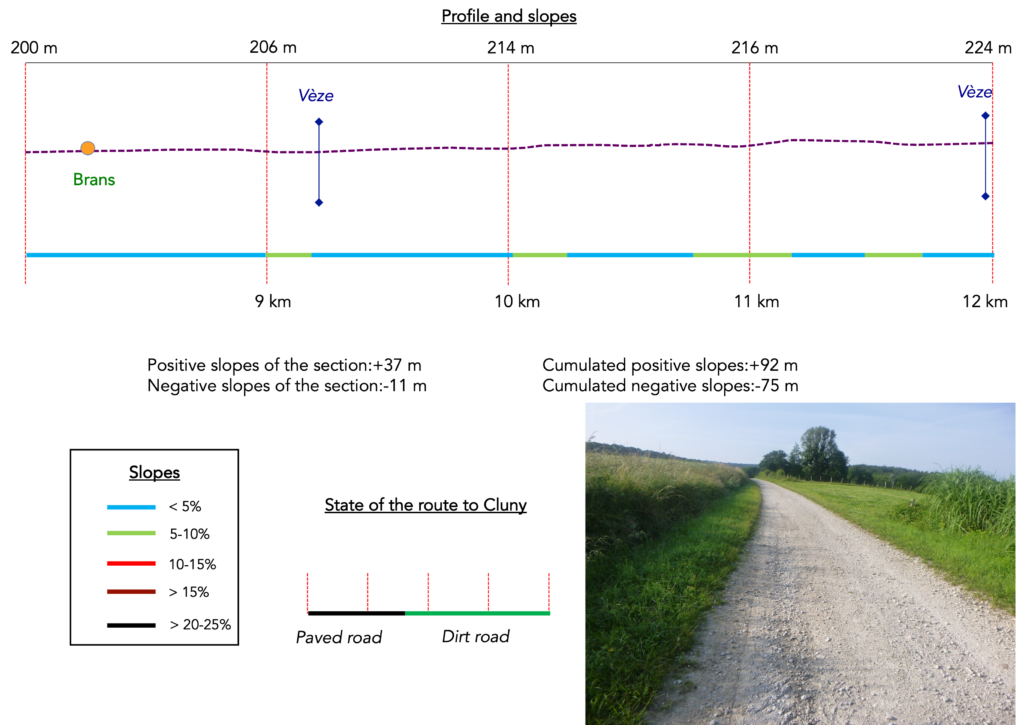

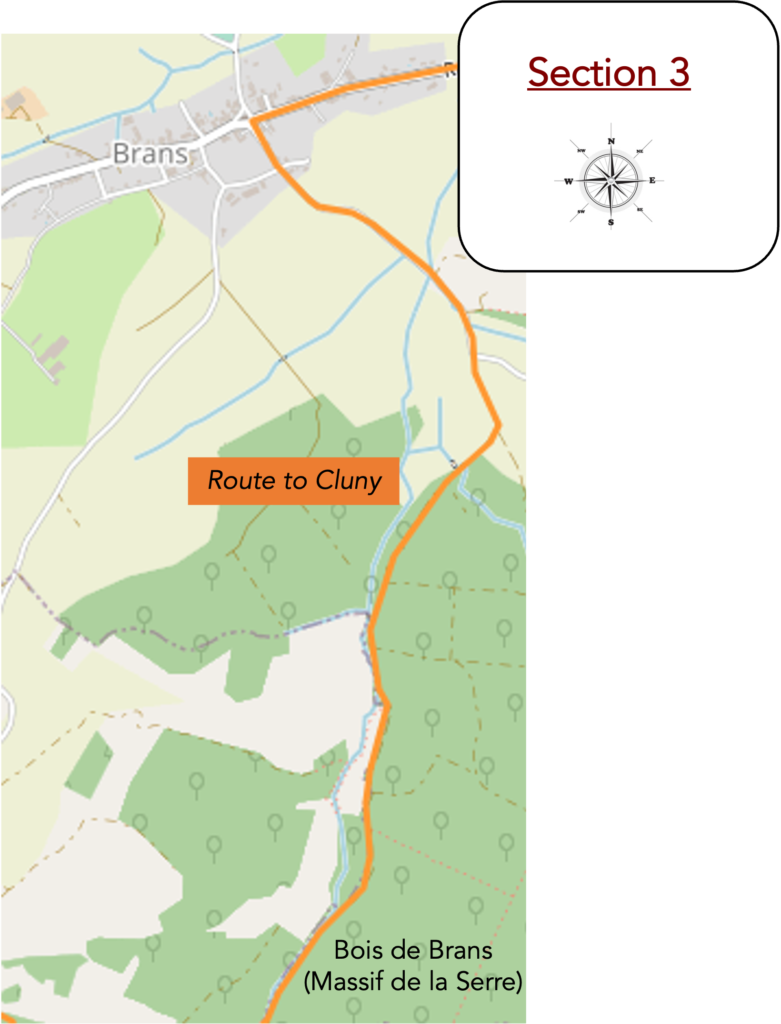

Section 3: In the countryside of Brans before the woodland

Overview of the route’s challenges: a route with no difficulty.

| The road then reaches Brans, a village stretched out like a ribbon, unfolding leisurely along the road. Its stone houses, sometimes modest, sometimes proud, tell an old story, that of a community rooted in land and time. Here, the pilgrim’s step echoes on the asphalt like a familiar sound, welcomed by the discreet gazes of the façades. |

|

|

| The woman who runs the guesthouse, guardian of local hospitality, also holds the key to the church. With a smile, she will tell you that the pews inside are still numbered by family, as if the memory of lineages continues to reign over the nave. Sitting anywhere other than one’s assigned bench would almost be an offense against the old order. As for the lords of the nearby château, they naturally occupied the front row, a clear sign of their precedence within this village hierarchy. |

|

|

| The route soon breaks away from the village and regains its freedom, following the road as it moves off through the countryside. |

|

|

| The road undulates gently between meadows and cereal fields. Along the roadside, a discreet stream runs beside you, a thin ribbon of water whose murmur accompanies your steps. |

|

|

| A little farther on, the road passes in front of the washhouse fountain known as the Bataillé fountain. It is a charming site, almost secret, wrapped in nature’s embrace. One imagines the women of earlier times coming here far from the village to beat their laundry in rhythm with their conversations, weaving the clarity of water with the fabric of confidences. A short granite wall, placed like a punctuation mark, lends the place a romantic quality, as if time itself had paused here. |

|

|

| The route continues for a while on asphalt before opening onto a wide dirt path. Here, waymarking becomes rarer, but the direction is obvious: you must continue straight ahead, carried by the clear logic of the path. |

|

|

| Once again, this is the typical dirt path of the region, scattered with small sharp stones like shards of glass that ring beneath your soles. It gradually draws closer to the forest, as if attracted by a protective shade. |

|

|

On the hillside, the pilgrim’s eye soon catches the silhouette of the bell tower of Offlanges. Its spire rises into the sky, seeming so close that one might believe it could be reached in moments. But the illusion is deceptive: the route still holds many turns before yielding its secret.

| The path softens into gentle curves as it crosses an open woodland. Familiar species dominate: ash trees, hornbeams, beeches, and maples raise their trunks in quiet fraternity. At times, however, tall pines appear, dark sentinels that contrast with the lightness of the deciduous trees, bringing a more austere note to the landscape. |

|

|

| The path stretches on at length within this calm and repetitive atmosphere. From time to time, a scallop shell fixed to a trunk appears like a benevolent smile, reminding the walker that the way is correct. Yet there is little risk of losing one’s way here: a single path cuts through the wood of Brans. |

|

|

| Farther on, the Vèze stream once again meets the route, like an insistent companion, faithful at every bend. Its modest waters are nothing like a torrent, yet they charm through their constancy and clarity. |

|

|

| The path plays with the stream, moving away from it at times, then returning like you return to an old acquaintance. In certain places, the waterlogged ground becomes treacherous: even in dry weather, footsteps sink into the mud. It is a lesson in patience, where each stride demands heightened attention. |

|

|

Finally, the path turns right and crosses the course of the Vèze. A small footbridge, simple and modest, offers its wood or stone to allow passage. A tiny structure, yet indispensable, it marks the quiet triumph of the walker over natural obstacles.

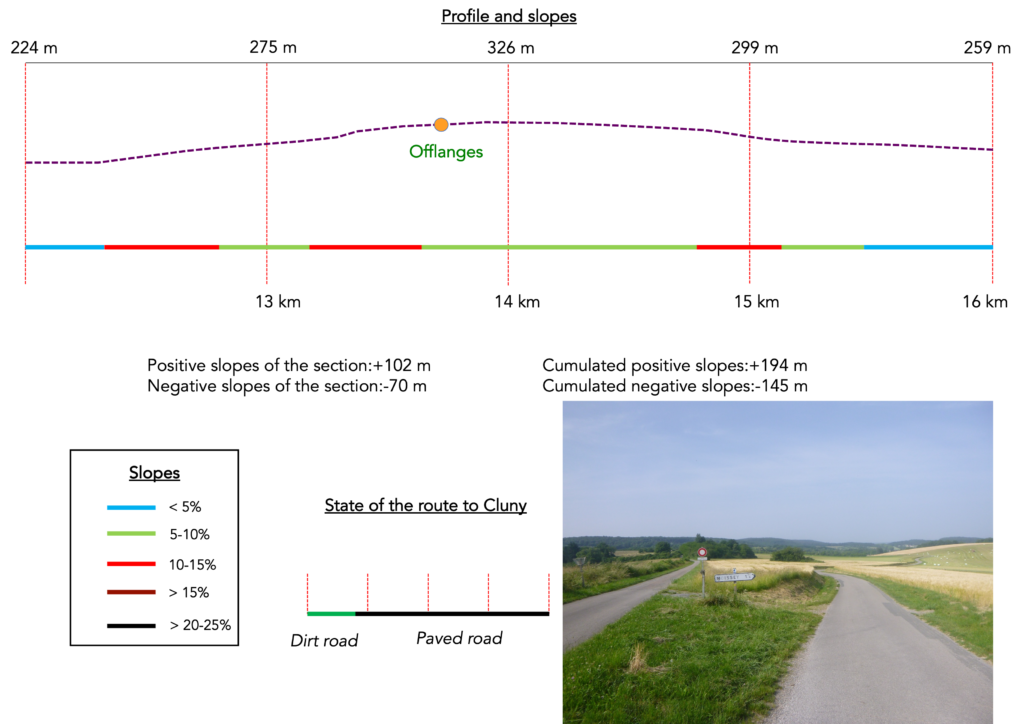

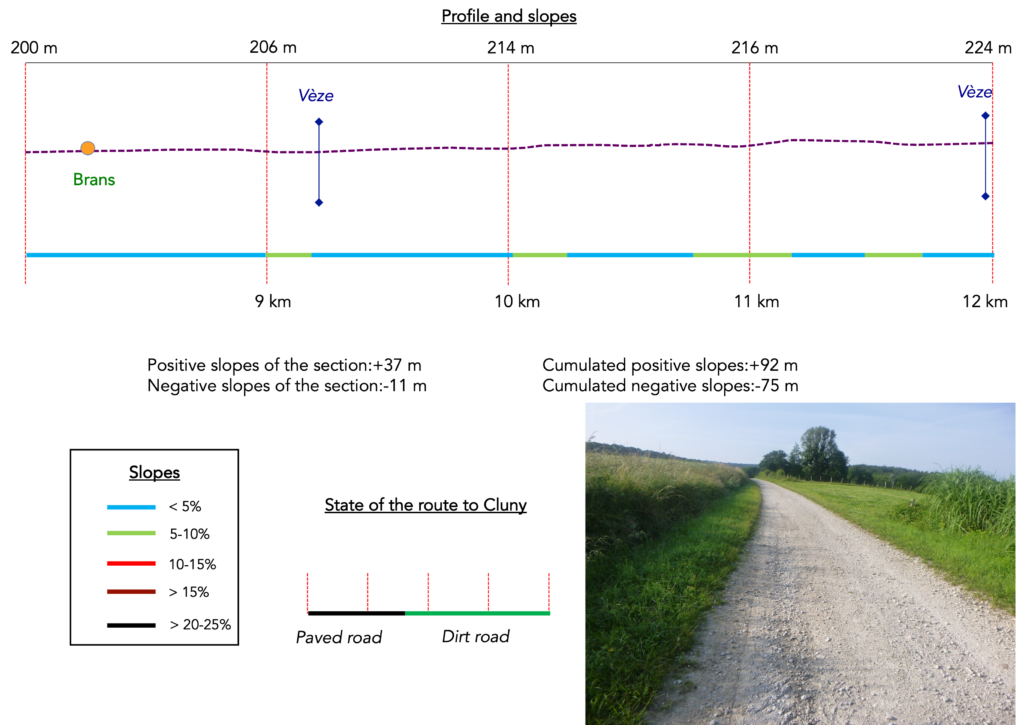

Section 4: The demanding climb toward Offlanges

Overview of the route’s challenges: slopes are often very steep along the route.

| After crossing the stream, the path lingers for a moment in the soothing shade of the woodland. The air remains humid, filled with the scents of ferns and fresh earth. But this forest respite is brief, for the clearing already announces itself, and the open world reclaims its space. |

|

|

| Soon, the slope becomes firmer and more assertive, as if the hill were calling you to order. The stony ground gives way to asphalt, and the gentle dirt path turns into a road where each step demands greater effort. The pilgrim feels this threshold in the legs: the ascent truly begins. |

|

|

| This road bears a name that fits it perfectly: the Chemin de la Serre. It clings to the slope, surging forward and then folding back, twisting lightly beneath the vault of trees. One might think it follows the capricious trace of a vanished stream, so much does it wind and play with the hillside. Dense foliage wraps it in a refreshing coolness, like a vegetal sanctuary at the heart of the effort. |

|

|

| Along this steep road, small cultivated plots appear here and there, like domesticated clearings in the midst of the woods. Modest yet proud patches of wheat sway gently in the wind, in the shade of tall ash trees and pines. |

|

|

| Then, at the bend of a switchback, the first houses of the village appear far above. At first tiny, they stand out like promises of rest. |

|

|

| By the roadside, a small granite cross, simple and discreet, rises like a sign of encouragement. It reminds travelers that every ascent is also a path of faith, a trial that countless footsteps have climbed before you. The stone, worn by centuries, holds the silent memory of all these presences. . |

|

|

| One last effort, one final surge, and at last the first houses of Offlanges are reached. The village opens itself to you, both humble and welcoming, like a promised halt for the pilgrim who has mastered the slope. |

|

|

| The Chemin de la Serre ends where it meets the departmental road D243, beside an old well from another age. Its rim, worn smooth by time, tells of the simple gestures of former generations who came here to draw fresh water before modern life transformed their habits. |

|

|

| Offlanges then reveals its discreet charm. Its stone houses, often coated with ochre plaster, form façades in warm tones. One reads here the imprint of an ancient village, at once rugged and gentle, deeply rooted in its land. |

|

|

Almost at the center of the village, the church rises, sober and solid. Dedicated to Our Lady of the Assumption, it already occupied this site in the eleventh century. Entirely rebuilt at the beginning of the eighteenth century, it carries in its stones the solemnity of the centuries and the devotion of so many generations. Its imposing presence dominates the surrounding houses, like a protective mother watching over her children.

| Leaving the village, the route enters Rue de la Croisette. At the crossroads, another small stone cross welcomes the pilgrim, accompanied by a providential bench, an ideal place to catch one’s breath and pause in reflection. |

|

|

| The road then launches into the descent. At first straight, it crosses the countryside beneath a curtain of trees, punctuated by a picnic area, before passing a singular caravan cemetery, a strange immobile procession that intrigues and provokes reflection. |

|

|

| Gradually, the land opens up. Horizons widen, offering broad views over the plain and the distant rolling hills. It is a moment of breathing space, an invitation to lift one’s eyes and let oneself be filled by the grandeur of the landscape. |

|

|

| Lower down, the route branches off toward Moissey, one and a half kilometers away. |

|

|

| The road crosses meadows and a few wheat fields. It is haymaking season: tractors, true monsters of steel, accomplish in a single skilled movement what generations once did with the strength of their arms. They gather, compress, and wrap in a fluid mechanical ballet that fascinates even as it distances us from older gestures. The scythe of our ancestors suddenly seems to belong to a bygone era, erased by modernity. |

|

|

| A little more descent, and the road rejoins the plain, flattening out like an invitation to breathe after the efforts just made. |

|

|

| At the very bottom, it crosses the departmental road D37, near the cemetery of Moissey, a silent guardian of memory. |

|

|

And there, a rare surprise on this route where waymarks are sometimes elusive: proper directional signs finally stand upright, clear and reassuring. But the pilgrim already knows that this comfort will not last.

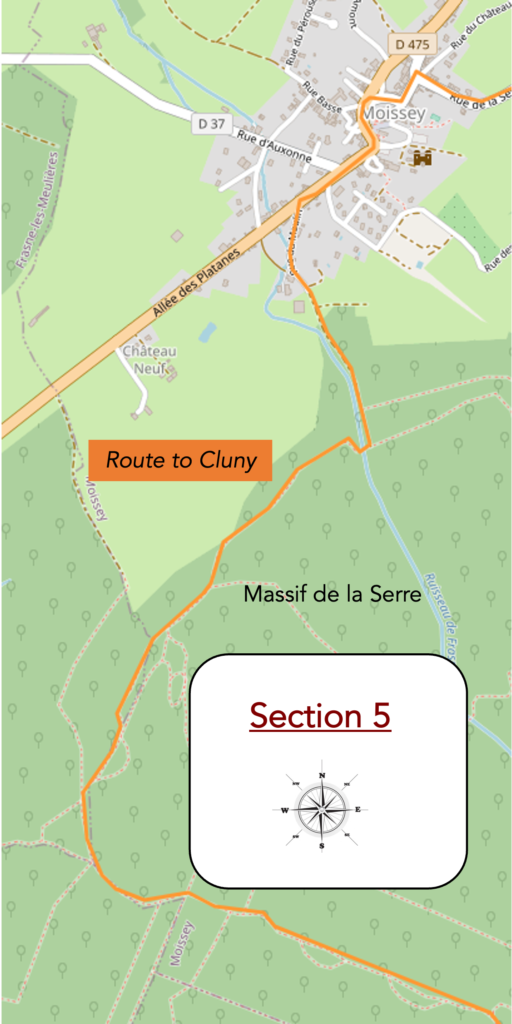

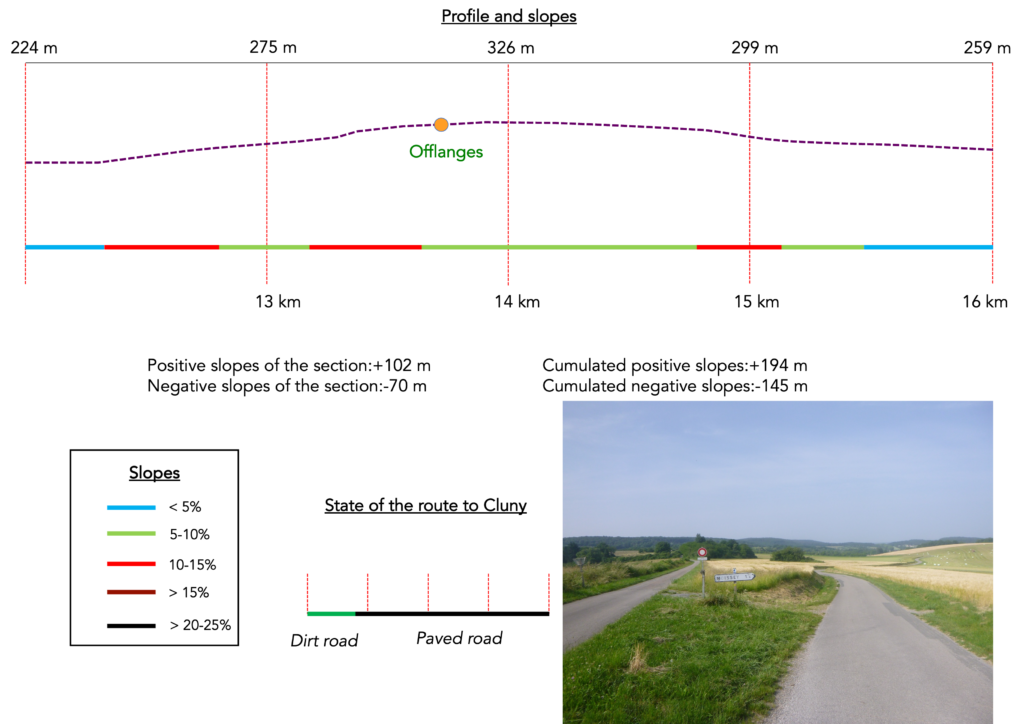

Section 5: A very bad path in the woods

Overview of the route’s challenges: slopes are often steep along the route.

| The road then reaches the entrance to Moissey. The village slowly unfolds before the pilgrim, like a long-awaited scene after the monotony of the plain. |

|

|

| The route then slips through the narrow streets, small paved and silent lanes, up to the church that dominates the town. Footsteps echo against the stone walls, adding a discreet rhythm to the serenity of the place. |

|

|

| The building is perched on the top of the hillside, imposing its silhouette over the modern village stretched out below. Dedicated to St Gengoult, a martyr forgotten by time, the church preserves in its choir and sanctuary elements dating back to the fifteenth century, silent witnesses to centuries of devotion. Its stones, gently weathered, seem to absorb the light like lanterns frozen in time. |

|

|

A very clear sign announces to travelers the continuation of the Way of Compostela: Ruisseau des Gorges in 800 meters, and the village of Menotey, still far away, more than five kilometers on. There is something reassuring in this clarity, a breath of orientation within the labyrinth of the world.

| The route then ventures into a pleasant park adjoining the château. The stones of the monument, with their drawbridges and machicolations shaped by centuries, evoke an imaginary great fortress. Although ruined in the fifth century and rebuilt in the eighteenth century, it has retained the soul of its origins. The path descends below, skirting the church and the château, to reach the main departmental road D475. |

|

|

| At the noisy crossroads, a fountain draws the eye. At once washhouse, watering trough, and fountain, now restored, it dates from the end of the seventeenth century and bears witness to the daily lives of washerwomen of the past. A nearby bakery and grocery shop offers a welcome pause, but the constant procession of heavy trucks descending from the Vosges toward Dole recalls modern life, relentless and hurried. |

|

|

| The route follows the departmental road for a short while before turning left into Rue du Moulin. The transition is gentle yet clear, like a breath that carries you away from the tumult of the crossroads and back toward the serenity of narrower ways. |

|

|

| This street leads to a reception center for dogs and cats, a small domestic interlude in the midst of nature. |

|

|

| From here, a stony dirt path begins its slow climb toward the forest. Stones crunch beneath each step. |

|

|

The path soon reaches the place known as Ruisseau des Gorges, indicating La Meulière at 1.6 km and Menotey at 5.4 km. Here, the pilgrim feels the transition: the civilized world gradually recedes, and nature reclaims its dominion.

| At first, everything seems simple. The wide path follows the peaceful stream. But this impression of tranquility is deceptive. One quickly senses that the route is leading into rougher nature, where each step demands attention. |

|

|

| Then begins a harsh ascent of 1.5 km through marshy woodland, cut through by mountain bikers who have churned the ground. Even in dry weather, the soil gives way beneath your feet, turning each step into a small struggle with the mud. This is one of the most exhausting sections of the Way of Compostela, a trail that tests patience and balance. |

|

|

| Fortunately, amid this chaos, the scallop shell appears from time to time, even though it is always poorly oriented, like a lighthouse in the fog, reminding the pilgrim that the way has not been lost. These reassuring marks are beacons within the ordeal. |

|

|

| Around you, nature is both wild and exuberant. Tall deciduous trees stand impassive, while dense undergrowth and twisting roots set the rhythm of the walk. At times, the trail dries briefly, but the mud, a faithful companion, constantly reminds you of the nature of this slope. |

|

|

When you reach the place known as La Meulière, a feeling of deliverance takes hold. You have left the hell of the Bois de Grédisan behind, only two kilometers away, yet the village of Menotey still lies more than four kilometers ahead. Two routes lead to the village, but the pilgrim knows that the scallop shell must be followed, a faithful and indispensable guide.

| The path then changes character. Dry now, it winds along a ridge, a realm of hunting and wind, where pigeon hides and burrows betray human activity in this territory. Each hide seems like a sentry, silently observing travelers. |

|

|

| The surrounding forest becomes radiant. Sunbeams filter between gigantic trunks, illuminating pines, shaggy oaks, and full-bodied beeches. The spectacle is almost theatrical. Each tree seems to scrape the sky, each shadow dances with the light. |

|

|

| The scallop shells, sometimes visible, subtly mark changes in direction, while the pigeon hides play hide-and-seek within this mysterious enclosure. Nature and humanity coexist here with discreet and respectful elegance. |

|

|

| Farther on, the path reaches the place known as « Le Bois des Pères », located one kilometer from the « Croix Boyon ». The forest here is dense yet breathable, and the stony, stable path allows the pilgrim to recover a calm rhythm after the ordeal of the marshland. . |

|

|

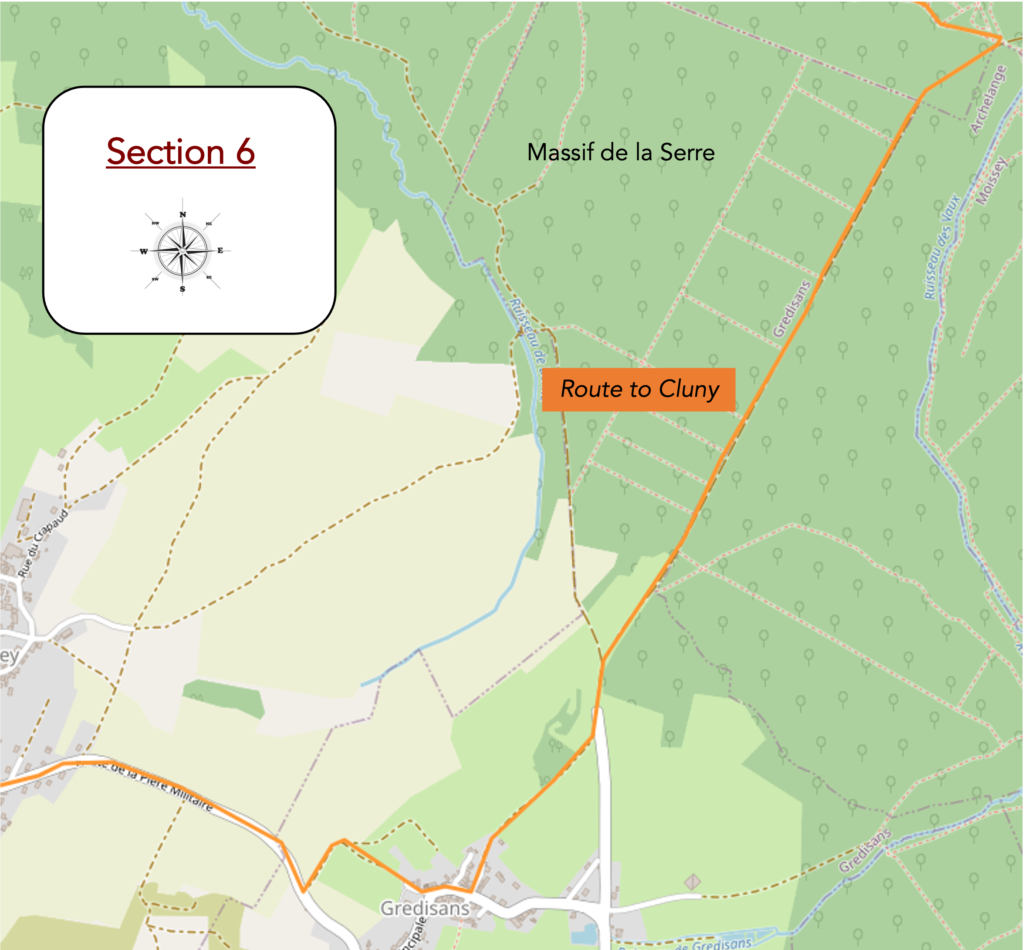

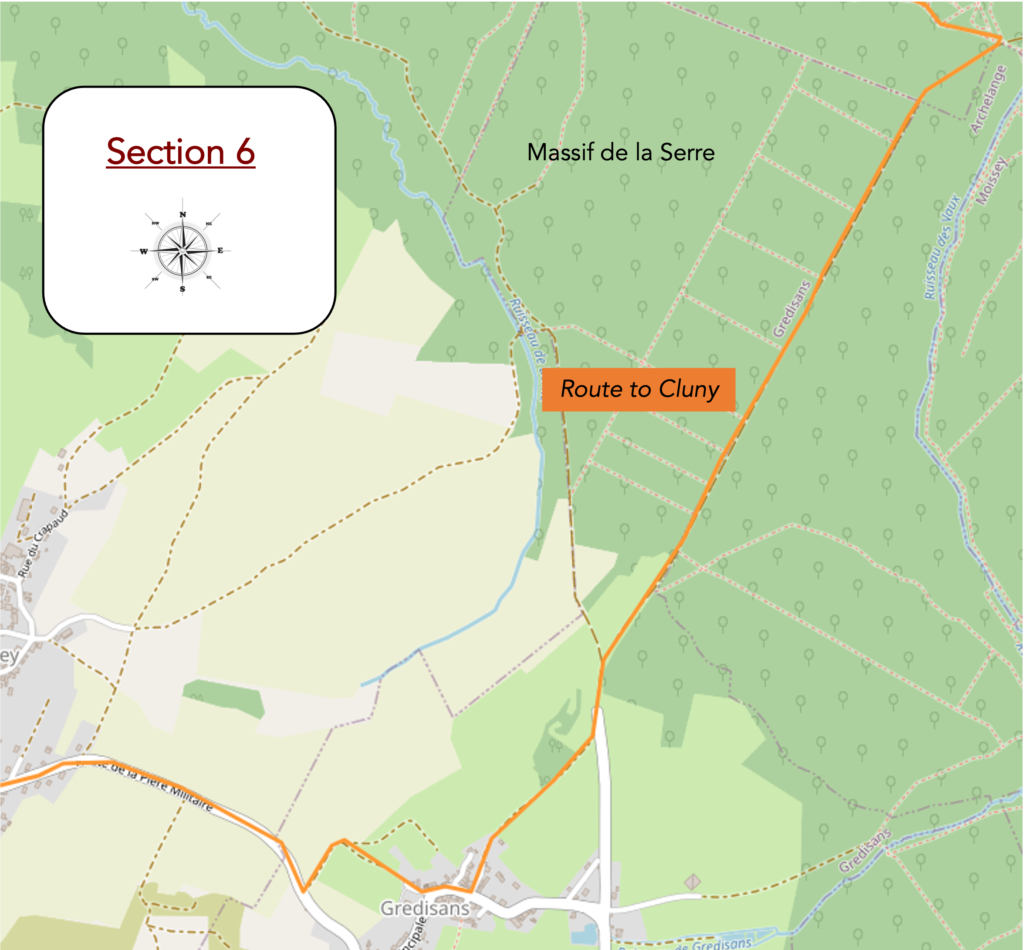

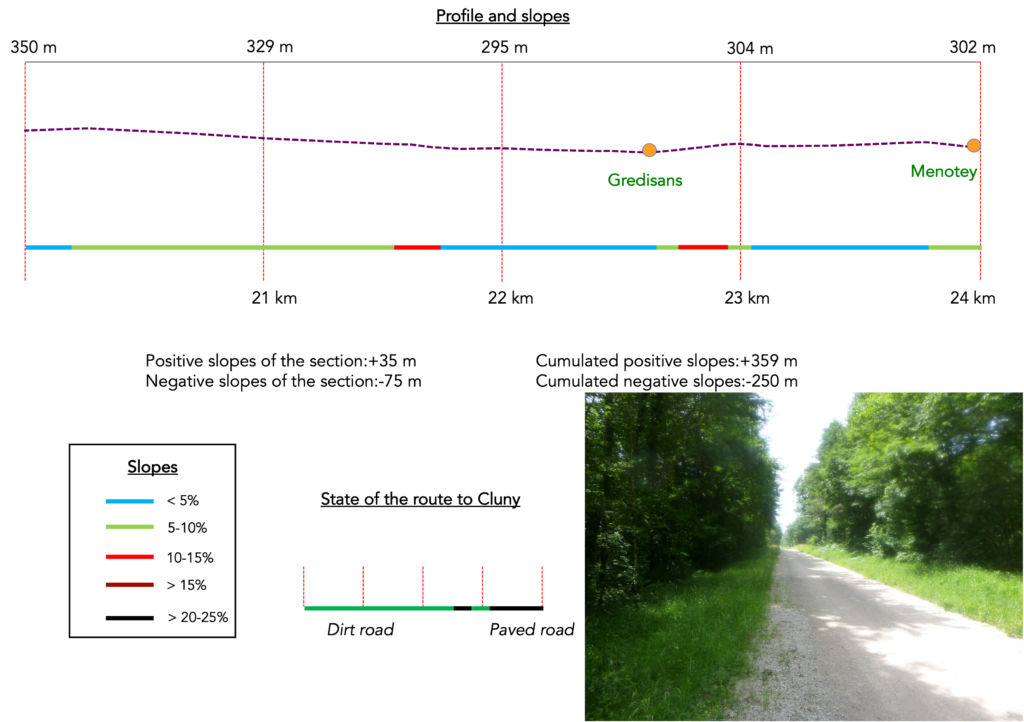

Section 6: Between groves and open countryside

Overview of the route’s challenges: a route without major difficulty.

| A trail continues to sway gently through the magical woodland, balanced between the ever-present scallop shells and the pigeon hides. The pigeons, unseen yet undoubtedly numerous, must be fluttering high above. Each step sounds on the damp earth, blending the murmur of leaves with the discreet clink of stones. |

|

|

| Here, the forest is managed with gentle rigor. Beeches and hornbeams, majestic and imposing, stand among the undergrowth, offering shaded shelter and a sense of permanence to the pilgrim crossing this vegetal realm. |

|

|

| The trail eventually emerges at the place known as “Sous la Croix de Boyon”. The “Croix de Boyon” itself stands two hundred meters higher, solitary and proud, but the route does not venture there. It is a fine stone cross, lost in nature like a forgotten sentinel, a silent witness to the ages. |

|

|

| A long, straight road of compacted earth then stretches through the forest, descending for more than a kilometer. This way, both peaceful and demanding, crosses a hunting area, which comes as no surprise given the pigeon hides encountered earlier in the woods. |

|

|

| Lower down, the path passes through the place known as « Le Chemin de la Poste », where a hunters’ lodge is tucked away, modest yet true to its purpose. Just nearby lies the hamlet of Grédisans, still invisible at this stage but already announced by signs of human presence. . |

|

|

| The road crosses a stone cross and continues its descent. All the crosses here seem to have come from the same mold, compact and low, as if shaped by a single hand, discreet yet dignified, recalling the devotion of generations past. |

|

|

| Before long, the route leaves the road to rejoin a dirt path that plunges into a grove. |

|

|

| It is a lovely, dark grove where dense hornbeams intertwine, drawing corridors of shade punctuated by sunbeams filtering through the branches. The atmosphere is intimate, almost secret, like a refuge for thoughts. |

|

|

| When the path leaves the grove, the first houses of Grédisans appear, nestled in greenery. The village feels peaceful and welcoming, with its farmhouses topped by well-kept roofs and filled with authentic character. |

|

|

| Drinking water is available here, though the fountains are discreet, suggesting that life follows a calm rhythm, sheltered from outside turmoil. |

|

|

| On leaving the village, the route heads toward the “Croix Denis”. It passes in front of the remains of mysterious walls, vestiges of a time when walls concealed secrets and protected forgotten lives. |

|

|

| Behind a rough stone bench, beneath a generous lime tree, near the fine stone cross, it is pleasant to stop and breathe. The path then climbs along the walls, gaining the crest, as if offering the pilgrim, a panorama of the surrounding world. |

|

|

| The path then ventures onto the wild ridge. Here, nature seems sovereign, free, and untamed. |

|

|

In the distance, on a still uncertain horizon, the hill of Mont Roland takes shape. The goal seems close, yet the journey continues, the distance remains tangible, and the summit still to be won.

| At the end of the path, the route meets the departmental road D79 and turns right, following the indication of the scallop shell’s arrow, a faithful guide, sometimes ironic in its approximations. |

|

|

| Today’s route alternates between long roads and isolated paths. Here, the pilgrim walks along the road for nearly a kilometer, eyes lost on the plain and the distant hills. |

|

|

| At the top of a gentle rise, the traveler reaches a stele known as the “milestone.” The name is misleading. Long mistaken for a Roman marker, it is in fact a Gallo-Roman funerary stele from the second century. The present reproduction pays homage to the original, preserved at the Archaeological Museum of Lons-le-Saunier. |

|

|

| Shortly afterward, the road reaches the place known as Le Faubourg, just a stone’s throw from the village of Menotey. The route bypasses the village center, preferring the discreet charm of its outskirts, and heads toward Jouhe, located three kilometers from here. |

|

|

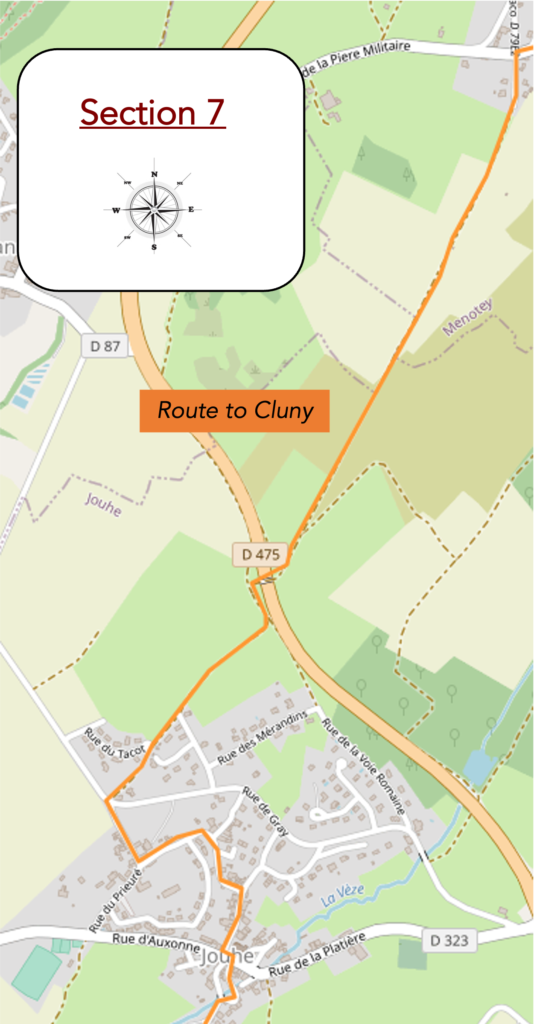

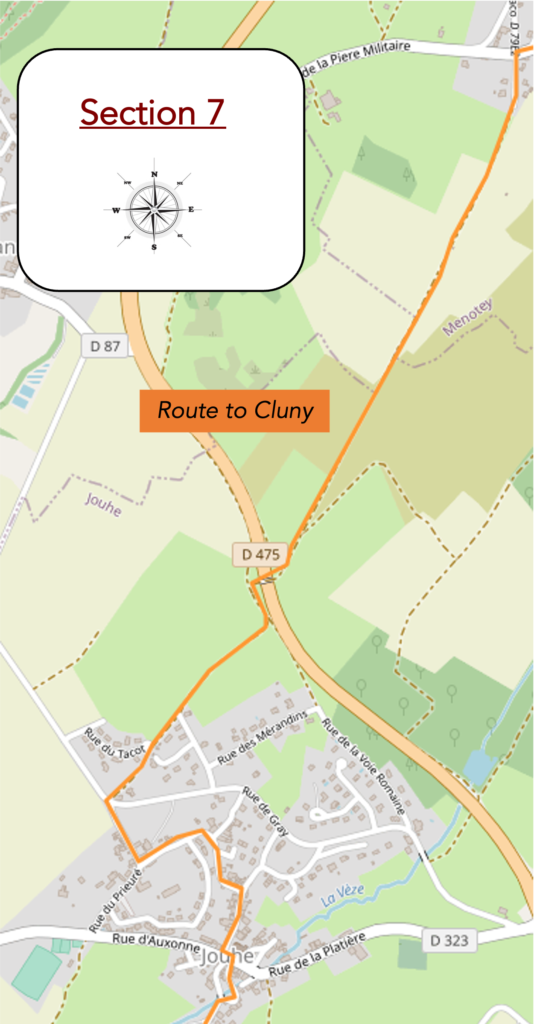

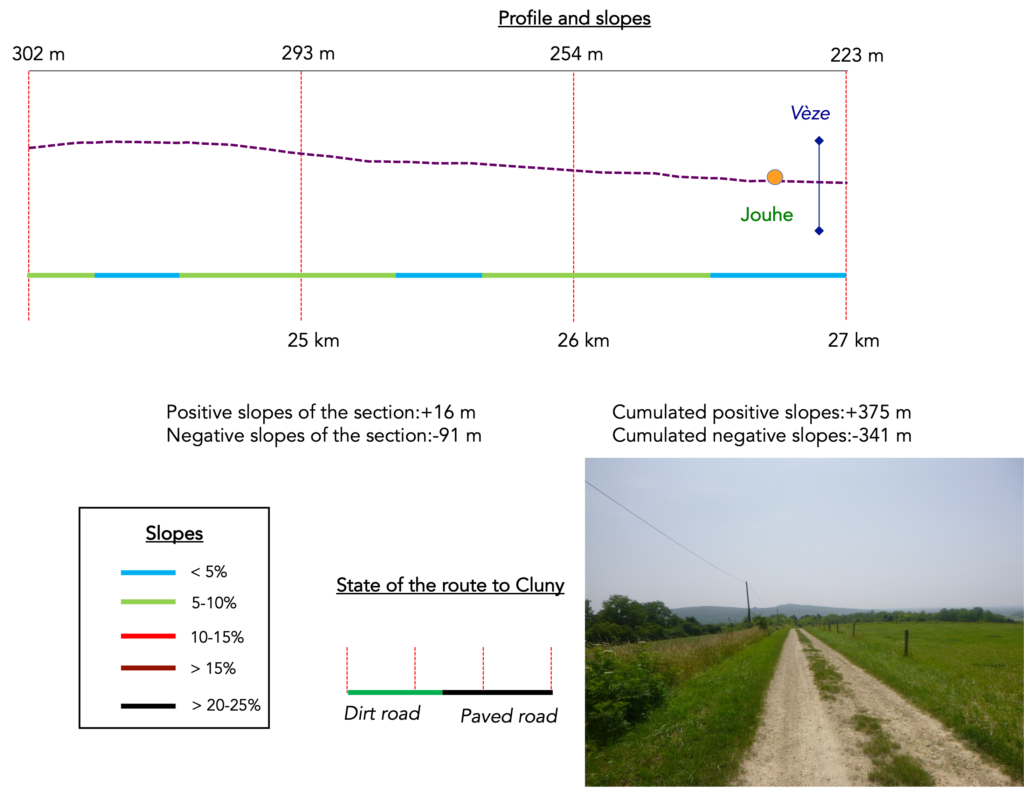

Section 7: With Mont Roland before your eyes

Overview of the route’s challenges : a route without difficulty.

| A stripped-back road then sets off along the ridge, wandering between wild grasses and the rolling lines of the landscape. It advances unhurriedly, as if carried by the breath of the wind and the calm respiration of the hills. |

|

|

| Soon after, it meets a stone Virgin, discreet and contemplative, sheltered beneath the soothing shade of chestnut trees. In this small park, the silent presence of the statue invites the pilgrim to pause for a moment, to turn inward in thought. |

|

|

| A wide path, generously strewn with stones, begins to climb gently toward the hill. Not far from a solitary antenna, cows graze freely, indifferent to the footsteps of travelers. |

|

|

| From the crest, the path softens, broad and peaceful. It descends almost imperceptibly, straight and less stony. Around it, bare meadows stretch open to the horizon. Ahead, almost constantly in view, rises the bell tower of the church of Mont Roland, still distant, a promise of arrival yet to come. |

|

|

| Lower down, the path slips into a light underwood. There, the bell tower sometimes disappears, as if playing hide-and-seek with the pilgrim, before reappearing farther on. The path changes character, sometimes smooth, sometimes dotted with stones, paced by this play of shadow and light. |

|

|

| At the end of the descent, the path crosses the major departmental road D475, noisy and familiar, already encountered at Moissey. The contrast is striking between the serenity of the path and the constant tumult of the road. |

|

|

| Immediately afterward, near a granite cross nestled beneath the foliage, the path bends gently, as if guided by the silent stone. |

|

|

| Once again, it escapes into the meadows, winding under the open sky. |

|

|

| Gradually, it approaches the road at the entrance to Jouhe, running alongside a shaded park where trees offer shelter to travelers. |

|

|

You then reach the place known as « La Grande Corvée », one kilometer from the center of Jouhe, and only 3.6 kilometers from Mont Roland. The horizon draws nearer, yet the pilgrimage still demands its share of effort and patience.

| The road then branches left, following the road to Gray. It runs alongside the park and moves slowly toward the heart of the village, as if hesitant to enter its intimacy. |

|

|

| A little farther on, the route turns right and descends gently toward the center. |

|

|

| The road crosses the square of the church of St Peter, a building shaped by centuries and transformations. Long attached to the convent of Mont Roland, this church bears the imprint of time, a witness to the spiritual history of the place. |

|

|

| Leaving the village, the road once again crosses the Vèze, this small watercourse that has accompanied the route so often in recent days. Here, the site is charming, where clear water harmonizes with the serenity of the surrounding trees. |

|

|

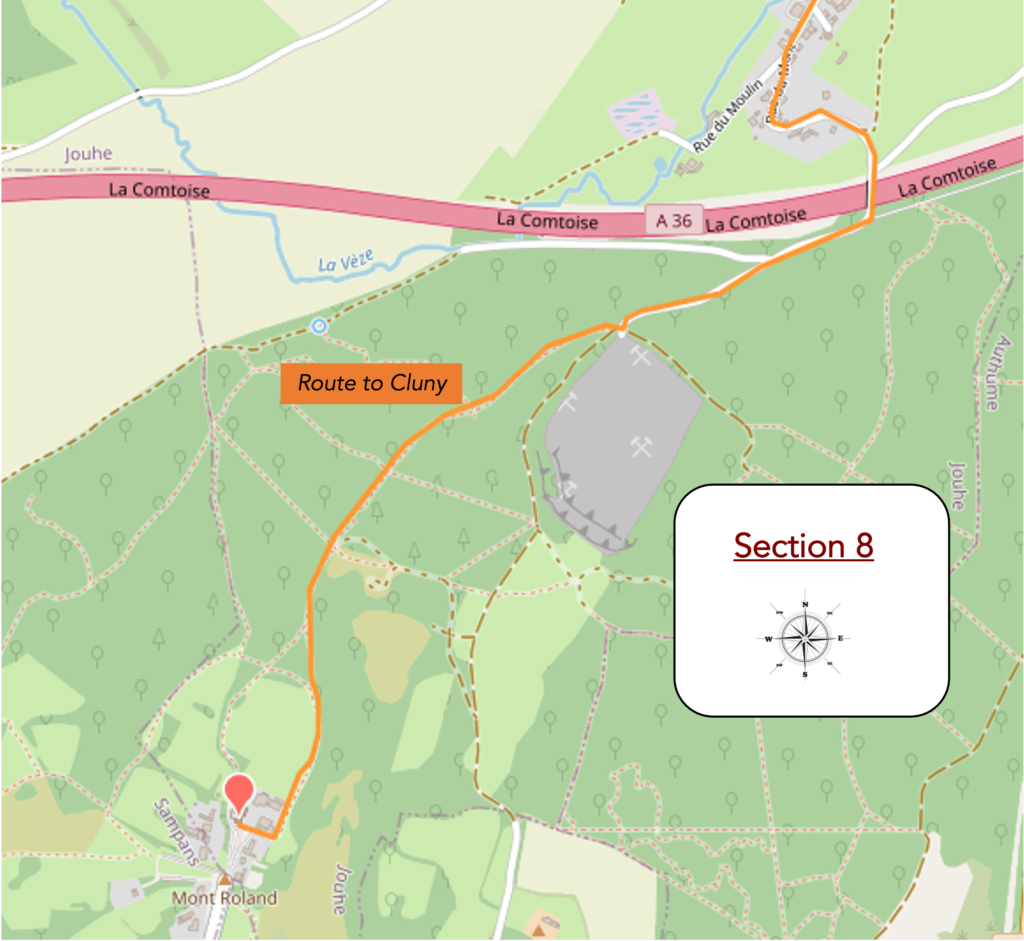

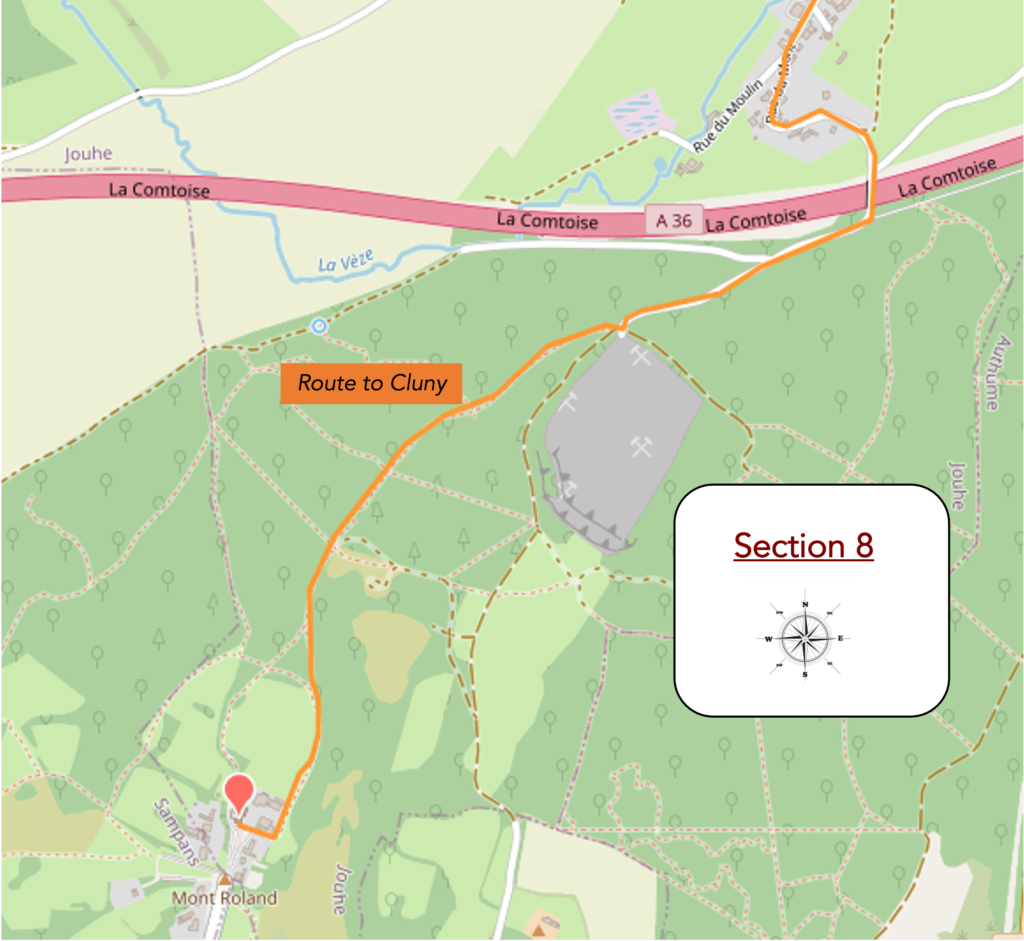

Section 8: On the way to Mont Roland

Overview of the route’s challenges : at times, a few steep slopes.

| The route then leaves the main road and slips away to the right. A small road, almost timid, begins to rise and quickly gives way to a path that climbs toward the heights. This is the Chemin du Mont, which here takes on the air of a solemn invitation. The pilgrim already senses entry into another dimension, that of expectation and approach, where footsteps align with hope. Every stone and every tuft of grass along the path seems to announce the ascent to come. |

|

|

| A wide path then slopes up gently beneath the foliage. The canopy of trees opens and closes like a woodland nave, where light plays as if through shifting stained glass. . |

|

|

| At the top of the first rise, the path meets a small paved road. The transition is surprising. After the intimacy of the woods, the asphalt appears as a hard line, a human scar laid across nature. Yet it is only a passage, a necessary link. |

|

|

| This road allows the crossing of the A36 motorway, which you will encounter again tomorrow along the route. Here, the contrast is stark. The constant hum of engines breaks the peace of the path. Yet from this mechanical tumult, the pilgrim retains only a distant echo, like a reminder of the modern world from which one has willingly stepped away. The bridge becomes a threshold. Behind lies the busy world, ahead rises the ascent toward the sacred. |

|

|

You are now at the place known as « Le Pont Vert ». From here, some pilgrims may yield to the temptation of heading directly to Sampans, thus avoiding the climb to Mont Roland. But to do so is to deprive oneself of an essential stage, to turn away from an inner experience. To bypass Mont Roland is to renounce the encounter. Yet there are always those who prefer to shorten time, as if the route were merely an obstacle. For others, by contrast, slowness is the very essence of pilgrimage.

| Packed earth then regains its rights. The asphalt fades away, and the wide path resumes its steady ascent toward the heights, bordered by thick hedges where deciduous trees intertwine. Walking recovers its natural rhythm, its ancient cadence. The climb, somewhat long and lacking shade, eventually becomes tiring. But the horizon soon opens up. A quarry exposed beside the path reminds us that the earth itself is cut into, extracted, and worked. |

|

|

You have now reached the « Carrefour de Jouhe ». Only 1.4 kilometers from Mont Roland, the final stage begins to make itself felt, like a summit waiting behind the last hill.

| The route then plunges into a narrow trail that leads back into the woods. Light dims, space tightens, and the walk becomes more intimate. It is as if the pilgrim must pass through one final green corridor before reaching clarity. |

|

|

| Here, nothing is new, and yet everything remains welcoming. Countless beeches raise their straight trunks like columns. Hornbeams spread their dense crowns. A few young oaks, stubborn and determined, reach toward the light. Maples complete this living architecture. The undergrowth breathes a soothing familiarity, never monotonous. |

|

|

| It is always the same forest, both gentle and mysterious, like a faithful companion. The ascent is not arduous. It is lived as an inward walk, a journey of the soul as much as of the body. |

|

|

Higher up, the trail reaches the “Carrefour de Saint-Jacques”. The name alone is a promise, a sign. Only 700 meters from the sanctuary, the pilgrim knows that the day’s fulfillment is close at hand.

| One more turn through the undergrowth, along dense brush, as if the forest wished to hold the walker a little longer before letting go. Then suddenly, space opens wide. The trail emerges onto a broad path in a clearing flooded with light. Mont Roland is there, almost within reach. |

|

|

| The efforts of the day then dissolve, swept away by the joy of approach. The path grows calm and curves around the trees. At the roadside, a Black Madonna welcomes the pilgrim. Draped in her dark wooden garments, she watches quietly and movingly. Her features seem carved to speak of fidelity and patience, as if she had always carried the prayers of those who pass by. |

|

|

| The walk circles the enclosure wall of the monastery. |

|

|

| The monastery stands on a large square beside an extensive park. An atmosphere filled with spirituality reigns here, for this is a major pilgrimage site. |

|

|

| A chapel is said to have been founded here in the fourth century by St Martin, followed by a monastery in the eighth century by Roland, nephew of Charlemagne, from whom the name Mont Roland derives. Officially mentioned in 1089 in a papal bull, it was attached to the priory of Jouhe. Plundered in the fourteenth century, it was rebuilt and the chapel became a church. Later, Jesuits and Benedictines settled here. During the Revolution, the Benedictines were expelled and the church became national property. The stones were sold. The sanctuary was reborn in 1843 after being repurchased by the Jesuits. Construction lasted an entire century. At the beginning of the twentieth century, lacking resources, the Jesuits were expelled from the region. With financial support, however, they were able to return until 1961. After the departure of the Jesuits, administration of the sanctuary of Our Lady of Mont Roland was entrusted to the diocese of St Claude. |

|

|

| The sanctuary of Mont Roland consists of the church dedicated to Our Lady, built between 1851 and 1870, where, in addition to pilgrimage services, several accommodations and a guesthouse are available to welcome itinerant pilgrims and organized pilgrimages. |

|

|

At the end of the long cloister, a magnificent and much-frequented hotel offers the well-earned rest that follows such a long stage.

LoOfficial accommodations in Burgundy/Franche-Comté

- Gîte Aubriot, 8 Rue du Puits, Offlanges ; 03 84 70 25 64 ; Gîte

- De Pierre et de Lumière, 5 Rue de la Platière, Jouhe ; 06 31 10 93 79 ; Gîte et chambre d’hôte

- Hôtel Restaurant Le Chalet, Mont-Roland; 03 84 72 04 55 ; Hôtel

Jacquaire accommodations (see introduction

- Thervay (1)

- Brans (1)

- Mont Roland (1)

Airbnb

- Thervay 2)

- Offlanges (1)

- Moissey (3)

- Jouhe (1)

Each year, the route changes. Some accommodations disappear; others appear. It is therefore impossible to create a definitive list. This list includes only lodgings located on the route itself or within one kilometer of it. For more detailed information, the guide Chemins de Compostelle en Rhône-Alpes, published by the Association of the Friends of Compostela, remains the reference. It also contains useful addresses for bars, restaurants, and bakeries along the way. On this stage, there should not be major difficulties finding a place to stay. It must be said: the region is not touristy. It offers other kinds of richness, but not abundant infrastructure. Today, Airbnb has become a new tourism reference that we cannot ignore. It has become the most important source of accommodations in all regions, even in those with limited tourist infrastructure. As you know, the addresses are not directly available. It is always strongly recommended to book in advance. Finding a bed at the last minute is sometimes a stroke of luck; better not rely on that every day. When making reservations, ask about available meals or breakfast options.

Feel free to leave comments. That is often how one climbs the Google rankings, and how more pilgrims will gain access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 12: Mont Roland to St Jean-de-Losne |

|

|

Next stage |