A hellish climb, a true canyon, and a river of pebbles

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

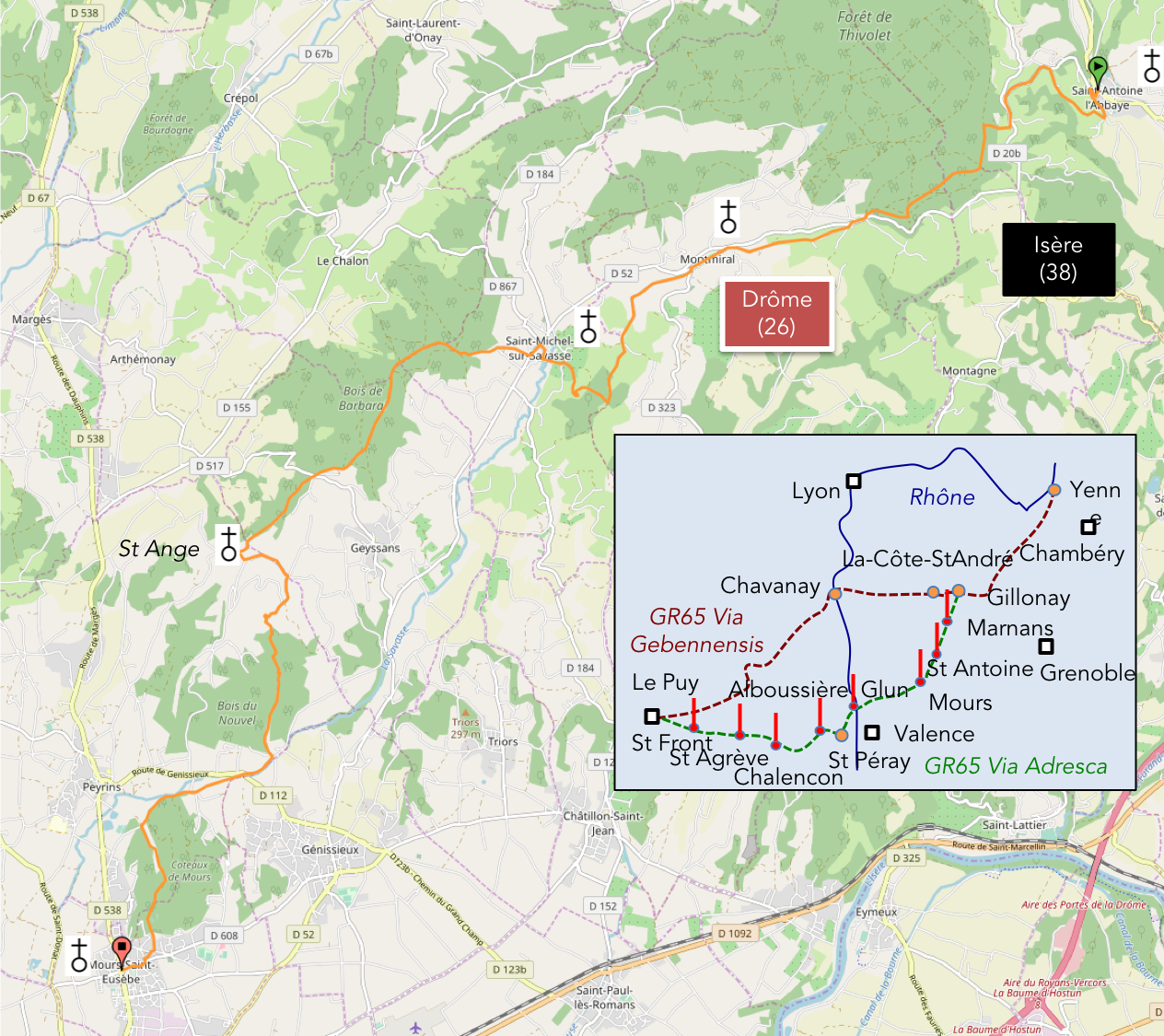

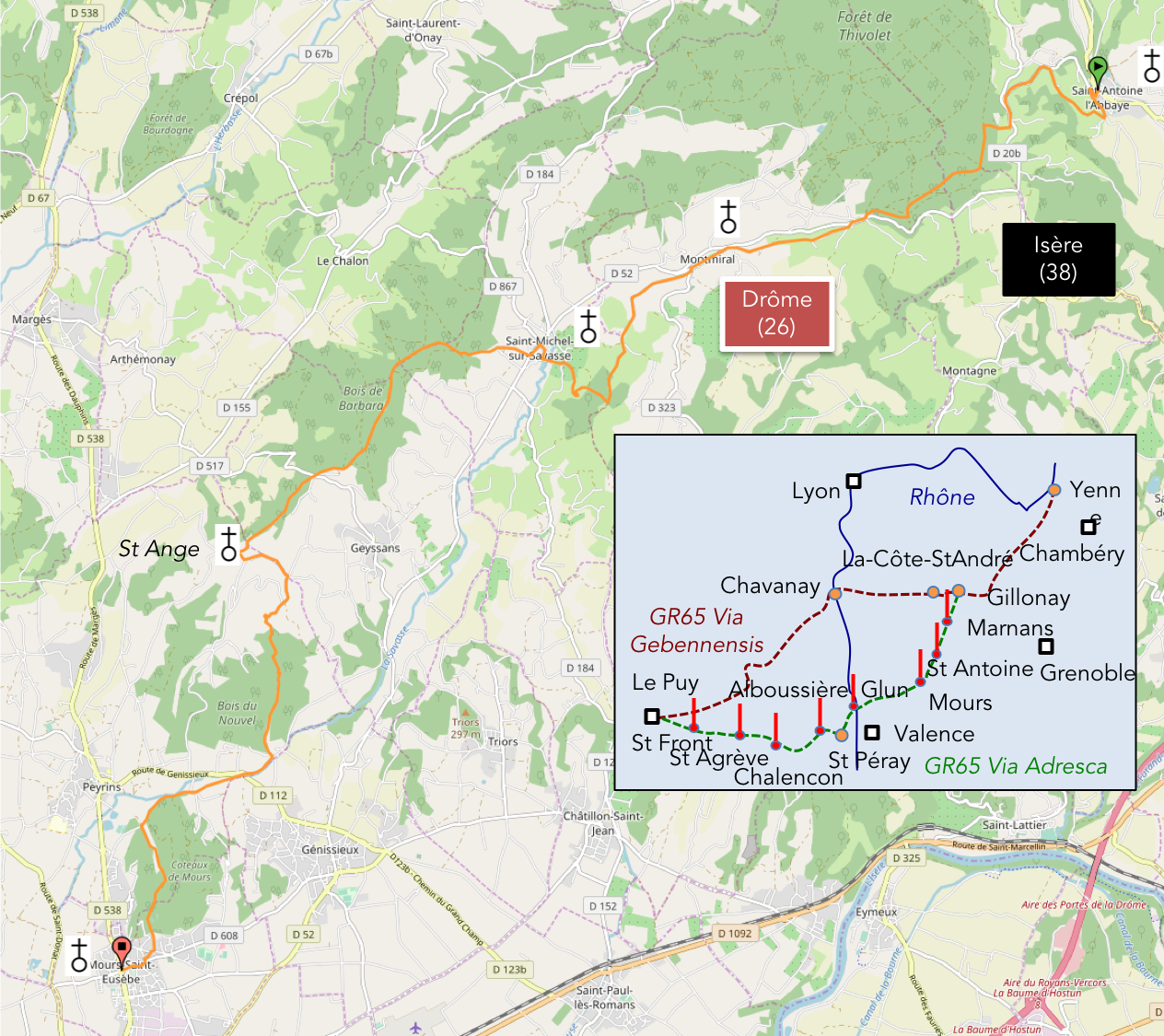

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-st-antoine-labbaye-a-mours-st-eusebe-par-la-via-gebennensis-adresca-32829624

| Not every pilgrim feels comfortable using GPS devices or navigating on a phone, especially since many sections still lack reliable internet. To make your journey easier, a book dedicated to the Via Gebennensis through Haute-Loire is available on Amazon. More than just a practical guide, it leads you step by step, kilometre after kilometre, giving you everything you need for smooth planning with no unpleasant surprises. Beyond its useful tips, it also conveys the route’s enchanting atmosphere, capturing the landscape’s beauty, the majesty of the trees and the spiritual essence of the trek. Only the pictures are missing; everything else is there to transport you.

We’ve also published a second book that, with slightly fewer details but all the essential information, outlines two possible routes from Geneva to Le Puy-en-Velay. You can choose either the Via Gebennensis, which crosses Haute-Loire, or the Gillonnay variant (Via Adresca), which branches off at La Côte-Saint-André to follow a route through Ardèche. The choice of the route is yours. |

|

|

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Today, brace yourself for an emotional whirlwind, a sequence of sensations as unpredictable as they are exhilarating. You leave the heights of Chambaran to descend into the Isère plain, but don’t expect a leisurely downhill stroll. The route mimics a roller coaster, taking you from steep climbs to breakneck descents, like a ghost train that gives you no respite. The route largely follows the course of the Savasse, a capricious river that most of the time seems forgotten, its deserted bed of abandoned pebbles a silent testament to the power of nature. Yet during violent storms, the river’s strength resurfaces unexpectedly, threatening the surrounding lands with its sudden fury. And that’s not all: the pebbles, far from confining themselves to the riverbed, lie scattered underfoot throughout the route. You’ll feel them at every step, an unrelenting presence. This rugged terrain, with its varied textures, becomes a fascinating yet unforgiving playground. Along the way, you’ll encounter places whose names alone conjure a sense of adventure: La Grande Combe and La Combe du Ravi. These areas, marked by untamed nature, challenge the soul of every hiker, beckoning exploration without end. What’s most striking about this stage is the stark contrast between the steep foothills and the proximity of the Isère plain. You’re just steps from civilization, yet it feels like you’ve been transported to another world. These are wild canyons and lush jungles, where dense vegetation and the shadows of trees create natural enclaves. In these untamed spaces, hikers and cyclists revel in thrilling challenges, surrendering to the pleasures of terrain that shifts beneath their feet. This is truly a remarkable stage for those who love off-the-beaten-path routes, unexplored trails, and the unpredictability of a journey. Every moment here promises surprises, and you’re never far from an unexpected discovery.

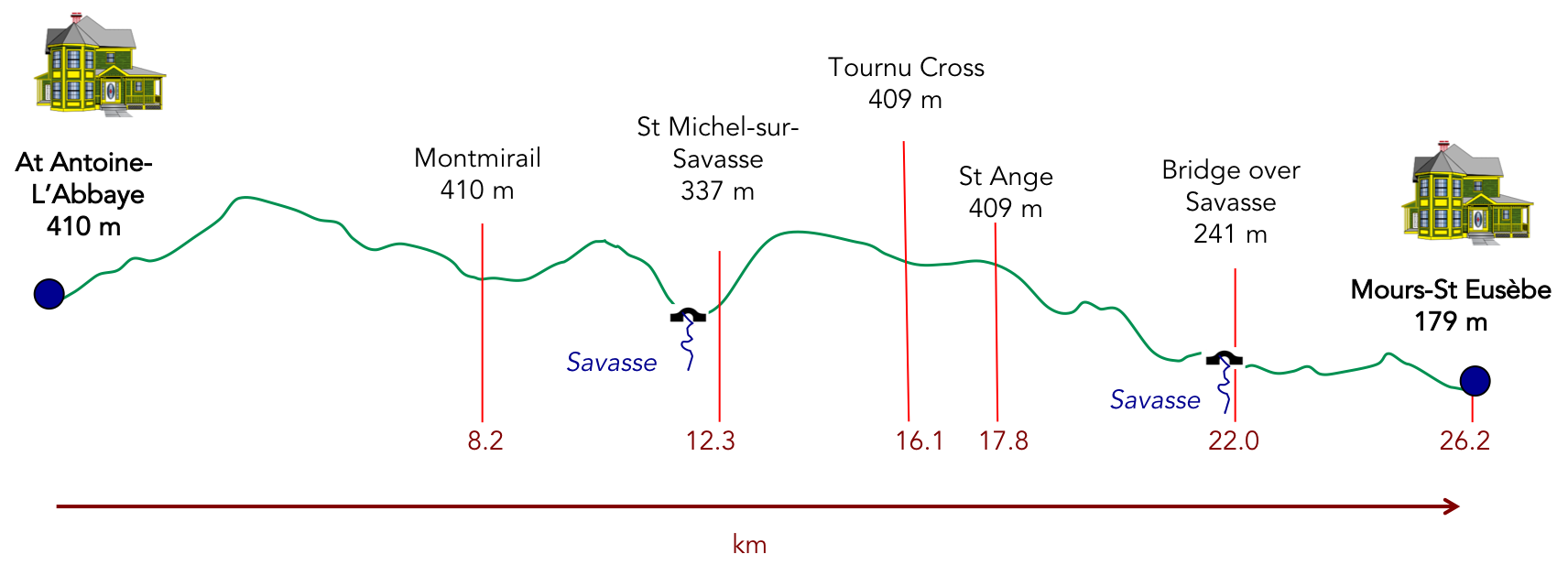

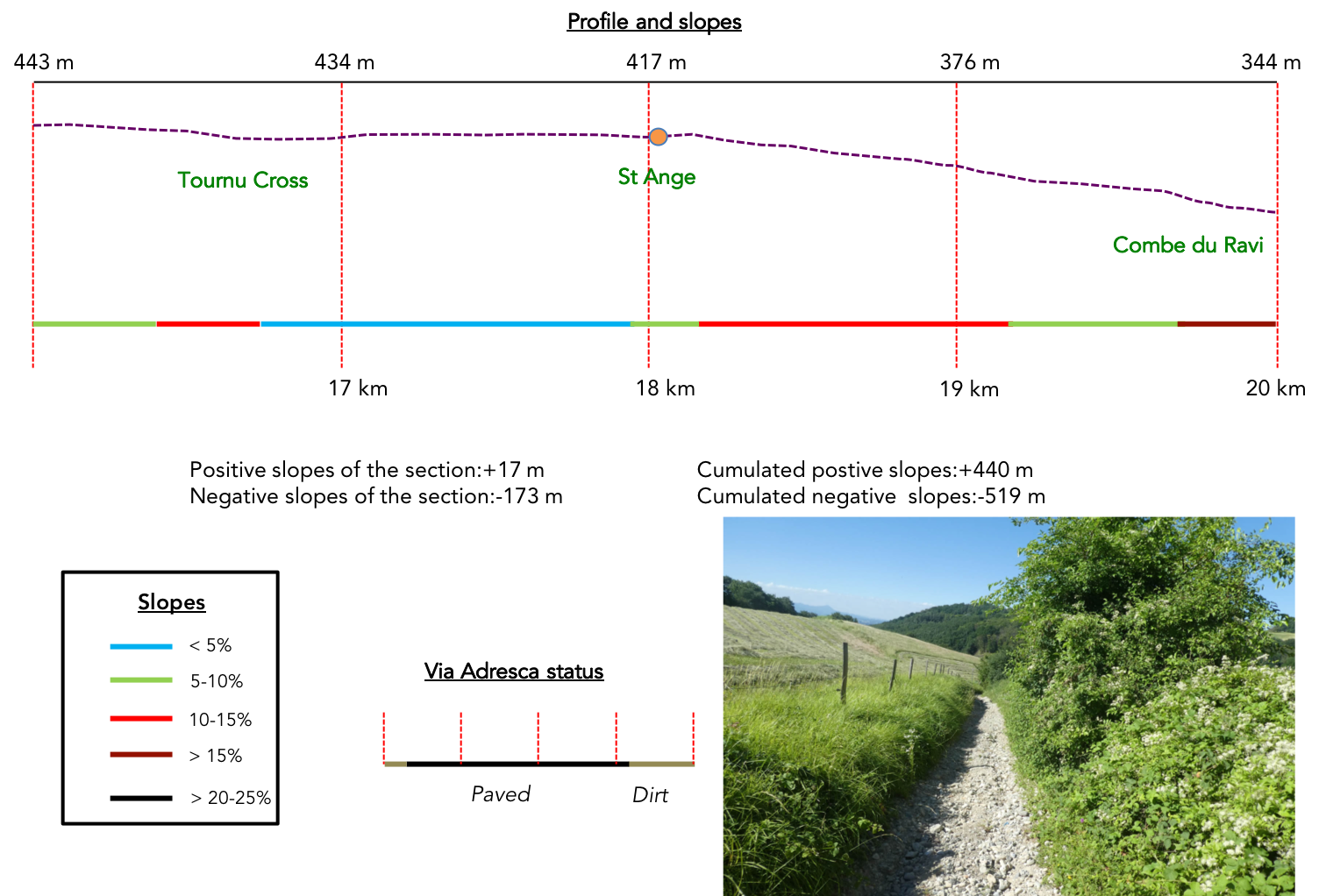

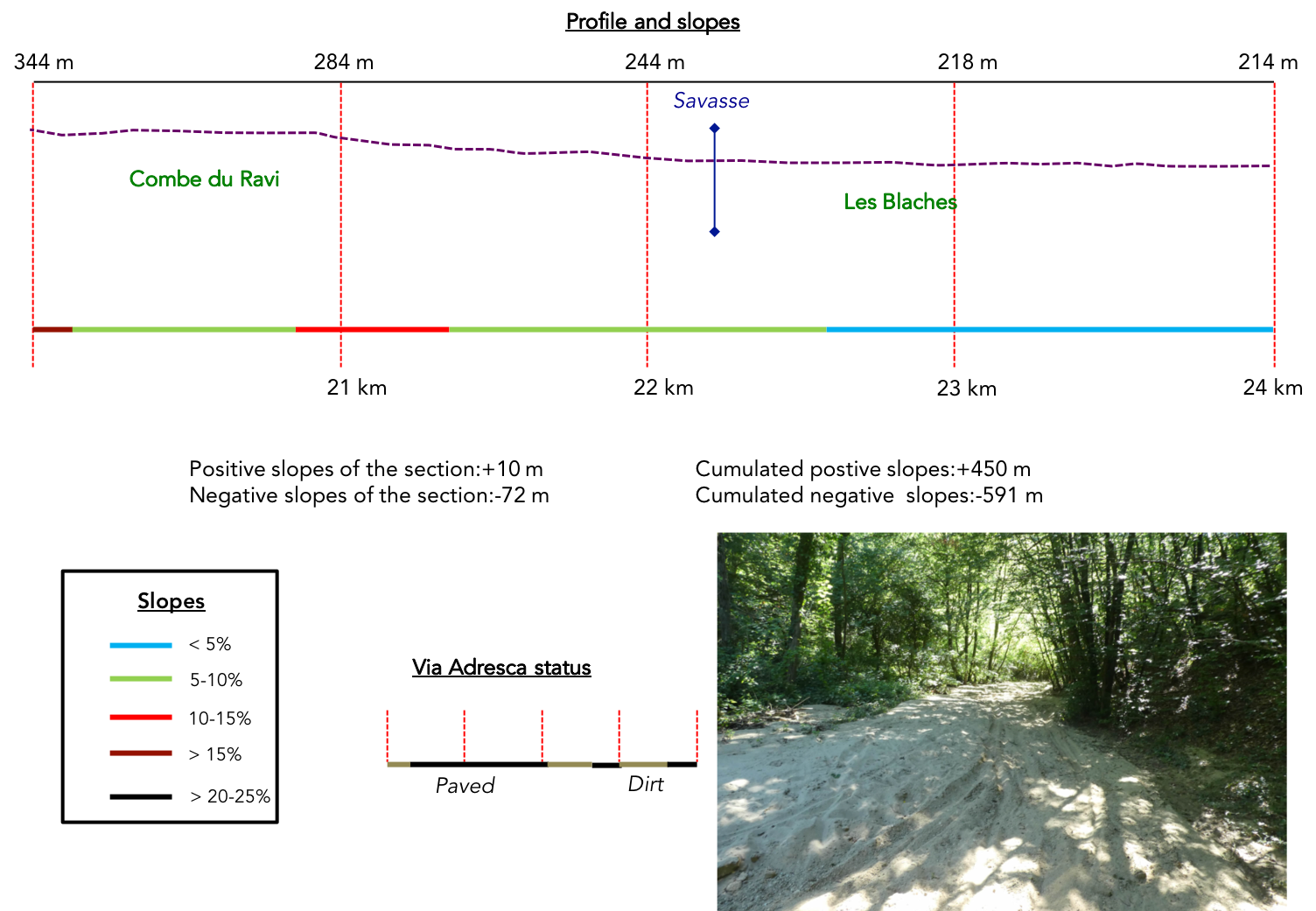

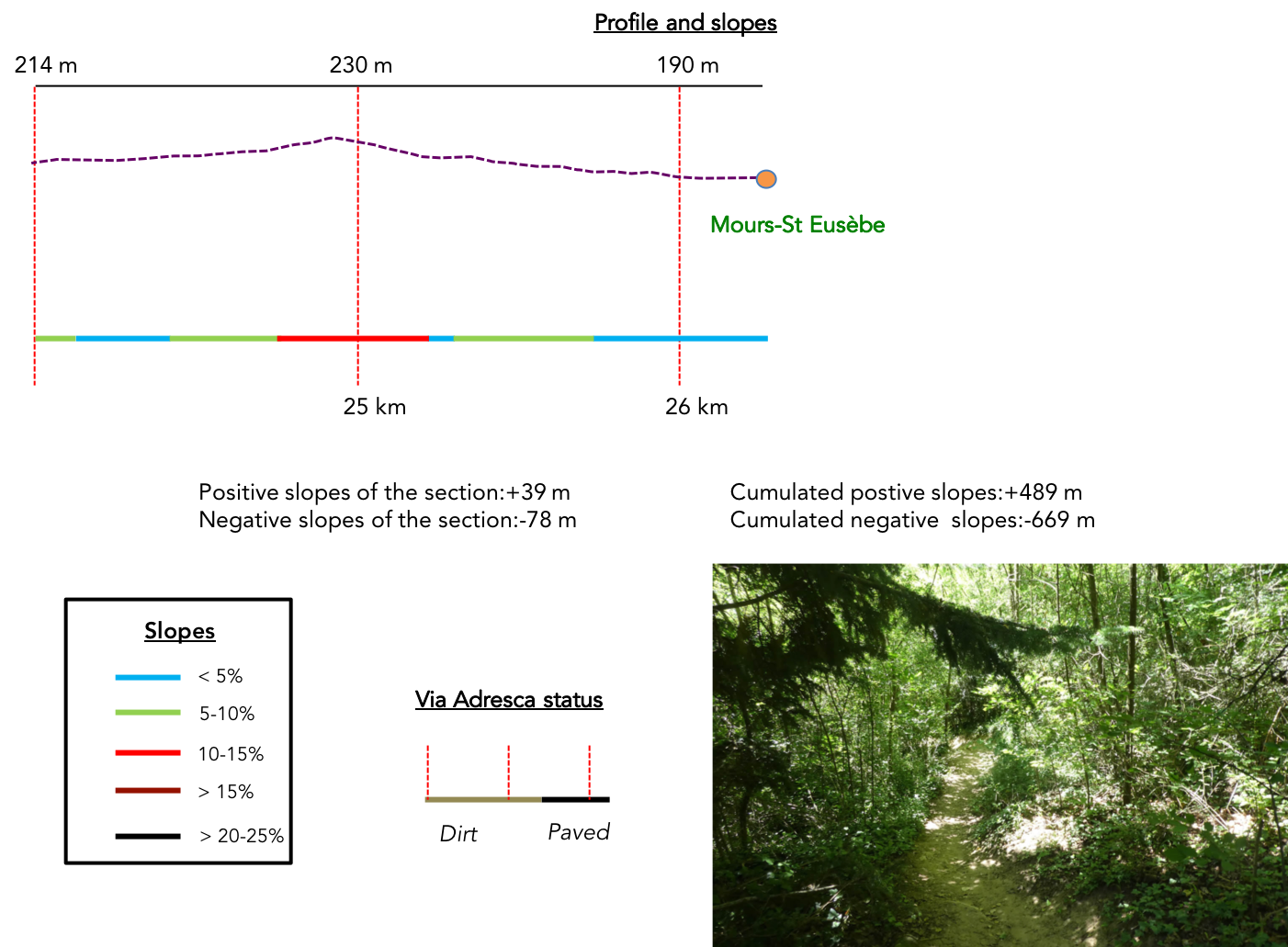

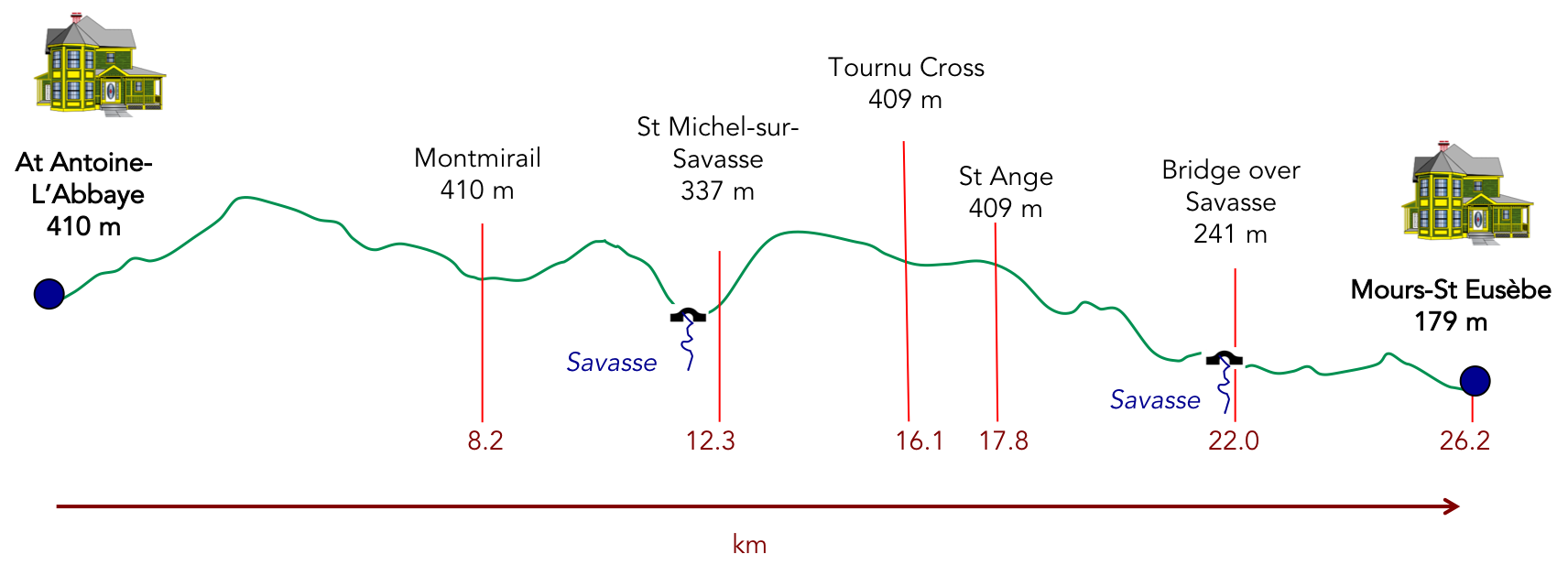

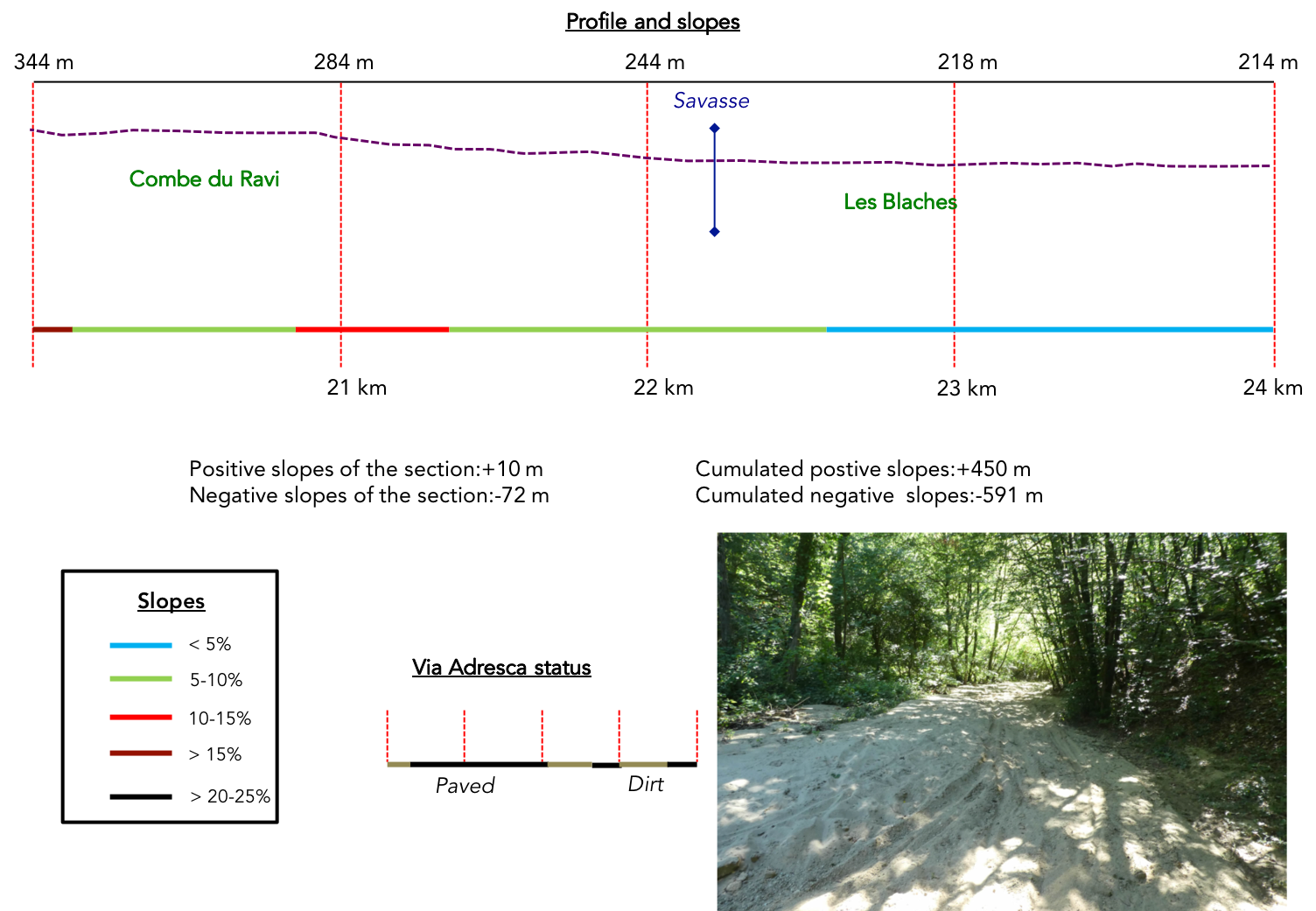

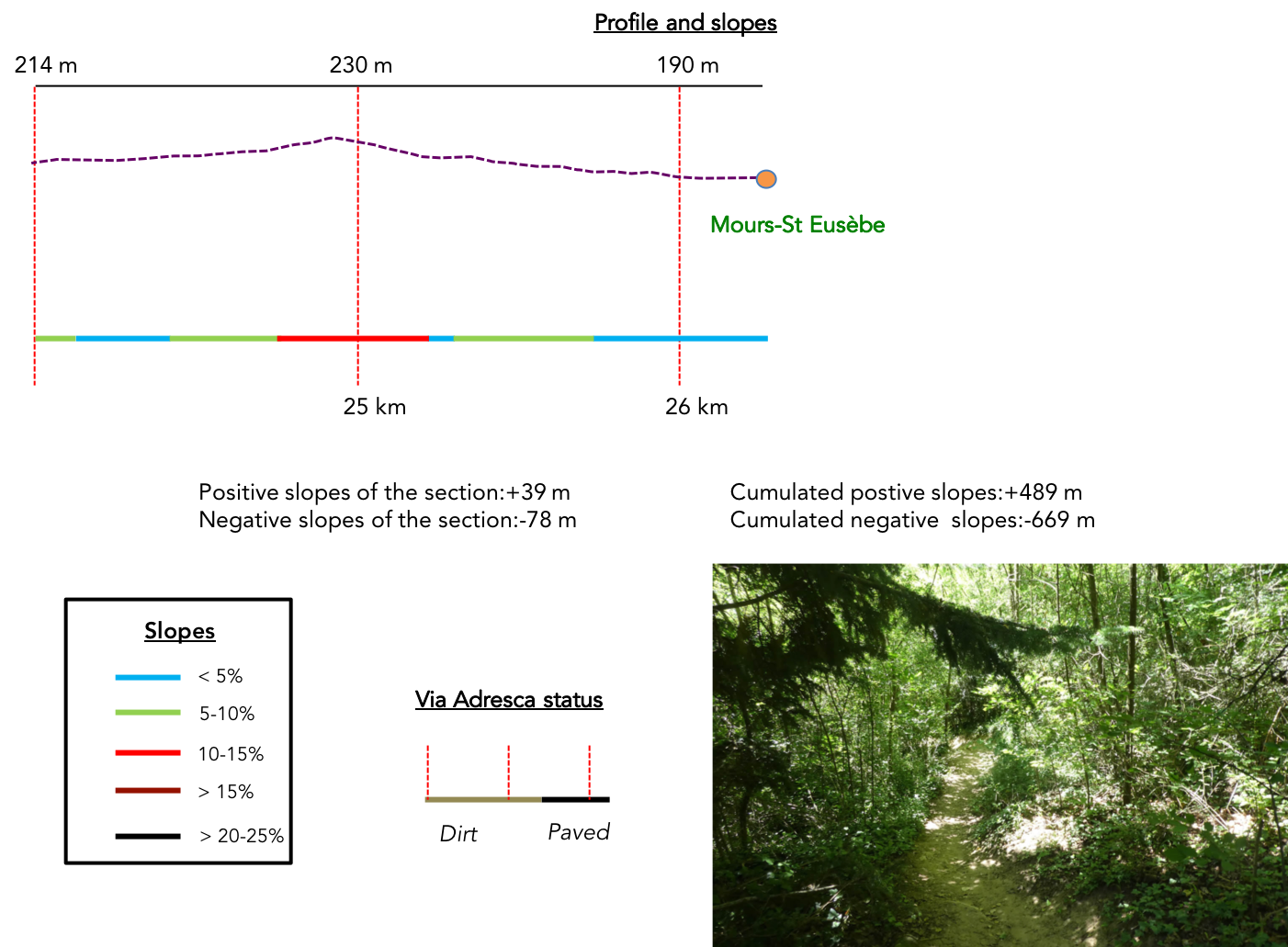

Difficulty level: The numbers might seem deceptive at first glance (+489-meters/-669-meters) over a 26-kilometer stage. These figures are manageable, but don’t be fooled. The route includes many flat sections, which may give an impression of ease. However, the real challenges emerge when the path climbs or descends over the pebbles. Stones roll underfoot, making the effort more demanding, climbs steeper, and every descent a test for your joints. The route begins with a long climb above St Antoine-l’Abbaye to reach the forests, with some steep sections along the way. The descent through the forest toward Montmirail is straightforward. The round hills become more pronounced as you approach St Michel-sur-Savasse, where the infamous climb of La Grande Combe begins. Once you’ve reached the top, the route becomes smooth sailing until you descend into the canyon of La Combe du Ravi, an absolute delight! From there, the route gradually calms, leading you to Mours-St Eusèbe, almost hidden within the thickets.

State of the Via Adresca: Today’s stage is equally split between paved roads and paths:

- Paved roads: 13.1 km

- Dirt roads : 13.1 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

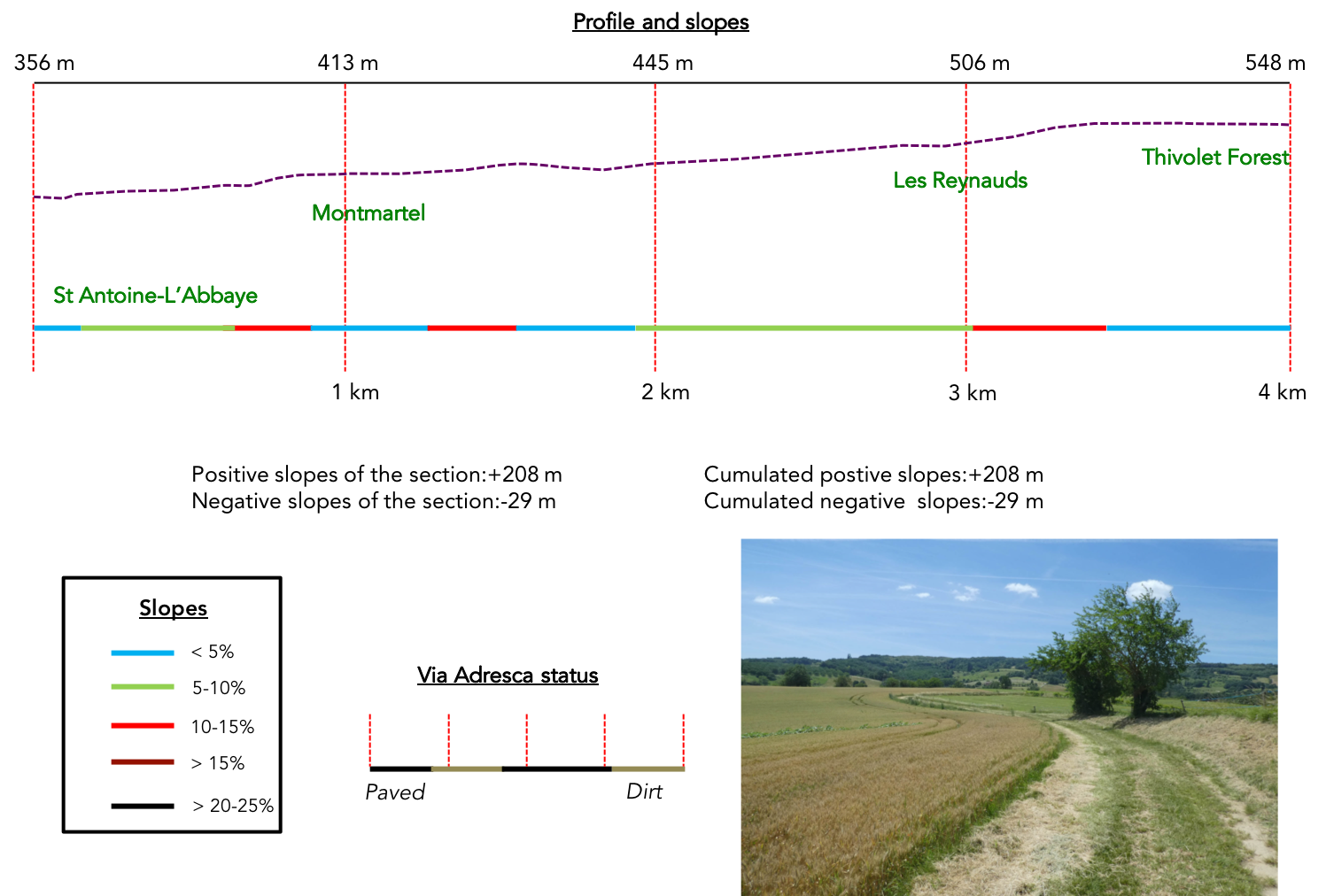

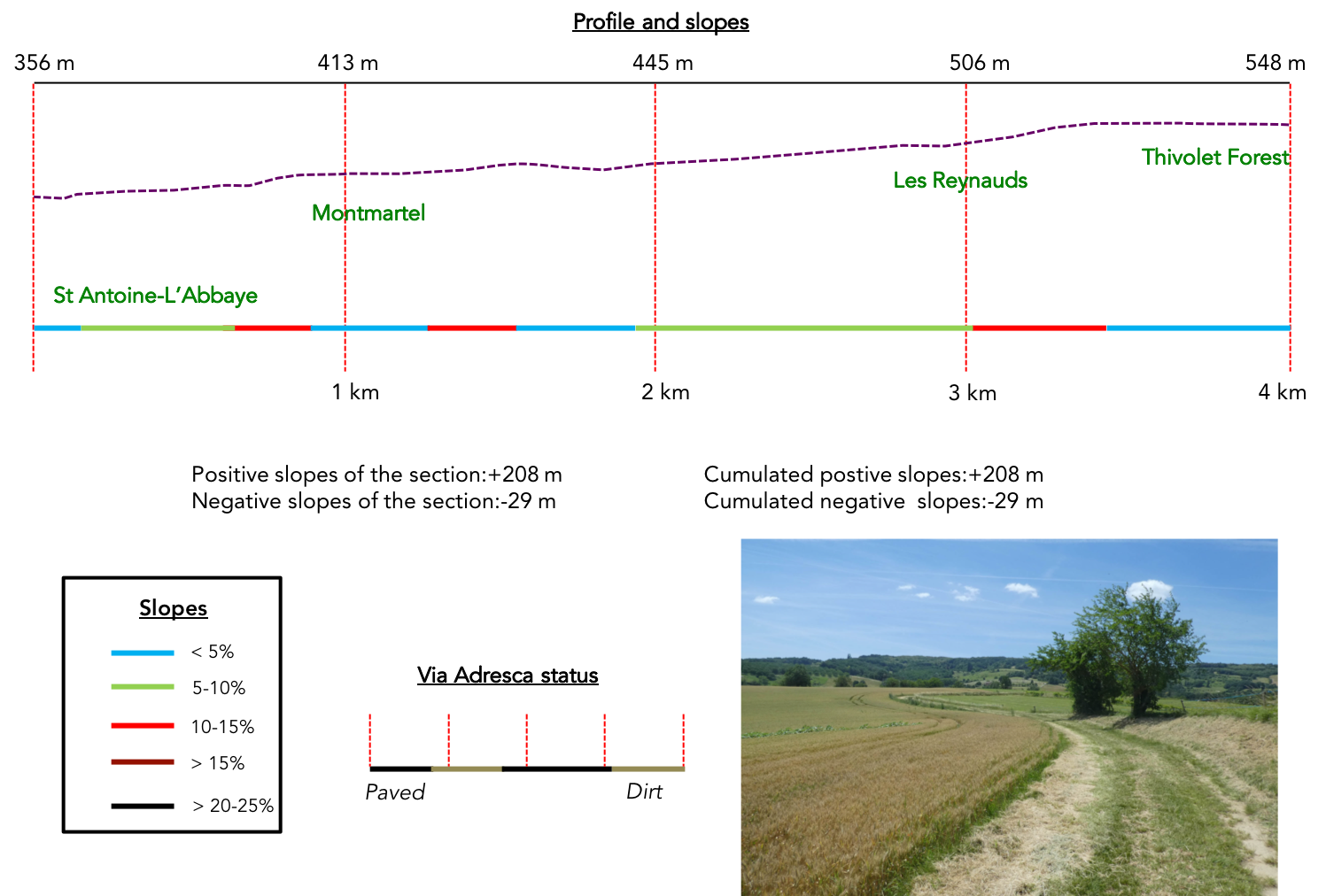

Section 1: Through the woods and meadows above St Antoine-l’Abbaye

Overview of the route’s challenges: A long, steady climb of nearly 4 kilometers, with slopes not exceeding 15%. However, there’s still 200 meters of elevation gain to overcome.

| The Via Adresca catches its breath at St Antoine-l’Abbaye, meandering through the narrow, winding alleys at the heart of the old village. This village, nestled in the protective shadow of its timeless abbey, seems similarly suspended outside of time. Its houses, imbued with the dignity of centuries past, reveal stones steeped in history, some even bearing an almost medieval austerity. |

|

|

| At the edge of the locality, the soft murmur of the Furand stream resonates in the narrow valley, where it winds beneath a canopy of leaves. This modest yet enchanting ribbon of water appears to gather the whispers of the past within its flow. |

|

|

| The Via Adresca follows the paved road to Romans, crossing a stone bridge. Though simple in design, the bridge is subtly marked by the wear of ages. Its polished foundations speak of accumulated memory, as if each stone was carefully placed to defy the erosion of time. The perched cabins of Fontfroide nestled among chestnut trees, are announced, offering a suspended refuge for those seeking a unique overnight stay. |

|

|

| Quickly, a choice arises: a fork in the road. Here, you must leave the main paved road to follow the smaller road to the left. If you’re seeking the Fontfroide cabins, this is also your path. Those persons traveling by car continue straight. |

|

|

| This hidden paved road is named the Route de Montmartel. It climbs steeply under a canopy of imposing trees. The slope and invites effort, soon rewarded by a striking view. |

|

|

| From this natural vantage point, the view encompasses the village and its abbey, a Gothic jewel nestled in a verdant basin. The abbey’s soaring arches and intricate facades, framed by its lush surroundings, amplify its mystical aura. |

|

|

| Higher still, the paved road reaches the hamlet of Montmartel. This is where you leave the Via Adresca if you wish to explore the Fontfroide cabins. To get there, a marked path leads for about a kilometer or more through hills where silence is broken only by rustling leaves and the occasional bird song. These cabins, cherished local landmarks, embody a pastoral escape suspended in time.

The Via Adresca, meanwhile, diverges from the paved surface, merging with a wide, rugged dirt path. Pebbles embedded in the ochre soil crunch beneath footsteps, creating a primitive melody audible to attentive walkers. |

|

|

| Soon after, the path opens onto a fertile plateau where well-ordered rows of crops stretch as far as the eye can see. Tall and majestic corn sways in the wind, while more modest oats ripple delicately like a moving Impressionist painting. |

|

|

| Then the path embarks on a winding dance through meadows, carried by a soft and soothing energy. The slope finally eases, as if the hill itself has been charmed by the surrounding tranquility. The pebbles, which grated underfoot until now, seem to vanish, giving way to a velvety green carpet. |

|

|

| All around are expansive, peaceful meadows stretching beneath a sky that seems to smile. Further along, the path ventures into a woodland where tall ash trees mingle with chestnut trees, eternal guardians of these lands. |

|

|

| Here, in the cool shade, the path reveals gray marl outcrops that contrast with the ochre soil. A few scattered Chambaran pebbles timidly reappear. At their base, small valleys cradle the gentle murmur of the Fontfroide stream and its countless tributaries, intertwining like the lines of an ancient parchment. |

|

|

| Exiting this wooded haven, the path continues its moderate climb before gently descending the side of a hill. As your gaze follows the descent, the Route de Romans appears in the distance. |

|

|

| The course emerges onto the small departmental road D27C, passing through the hamlet of La Bergère. Here, at the foot of an iron cross firmly rooted in a rock, nature reclaims its wild and untamed presence. This spot seems to offer a spiritual pause, a moment of reflection gifted to travelers by the solemn simplicity of the landscape. |

|

|

| The paved road then begins a prolonged but gentle ascent, winding along the hillside toward the forest. It is also here that vehicles take the road to reach the Fontfroide cabins. |

|

|

| At the top of this climb, the paved road joins the departmental road D20B. This quiet stretch appears to belong more to the grazing herds in the adjacent pastures. Charolais cattle, imposing yet docile, add a pastoral and almost picturesque touch. |

|

|

| After a few hundred meters along this departmental road, the Via Adresca veers off again, leading to the dead-end lane Impasse des Reynauds. Here, a small, daring paved road climbs toward the forest, inviting you to reconnect with the tranquility of the woods. |

|

|

| At the end of the lane, the path dives into the forest, and surprise, the Chambaran pebbles reappear, as if they were buried memories refusing to fade. The path climbs steadily through tightly packed chestnut trees, standing like an orderly army. Though steep, the climb is short. |

|

|

At the top of the hill, at the place called Thivolet-Woods, the pebbles disappear once again, and the slope softens. This is a strategic point to leave the Via Adresca and visit the celebrated treetop cabins, perched like secret nests between sky and earth.

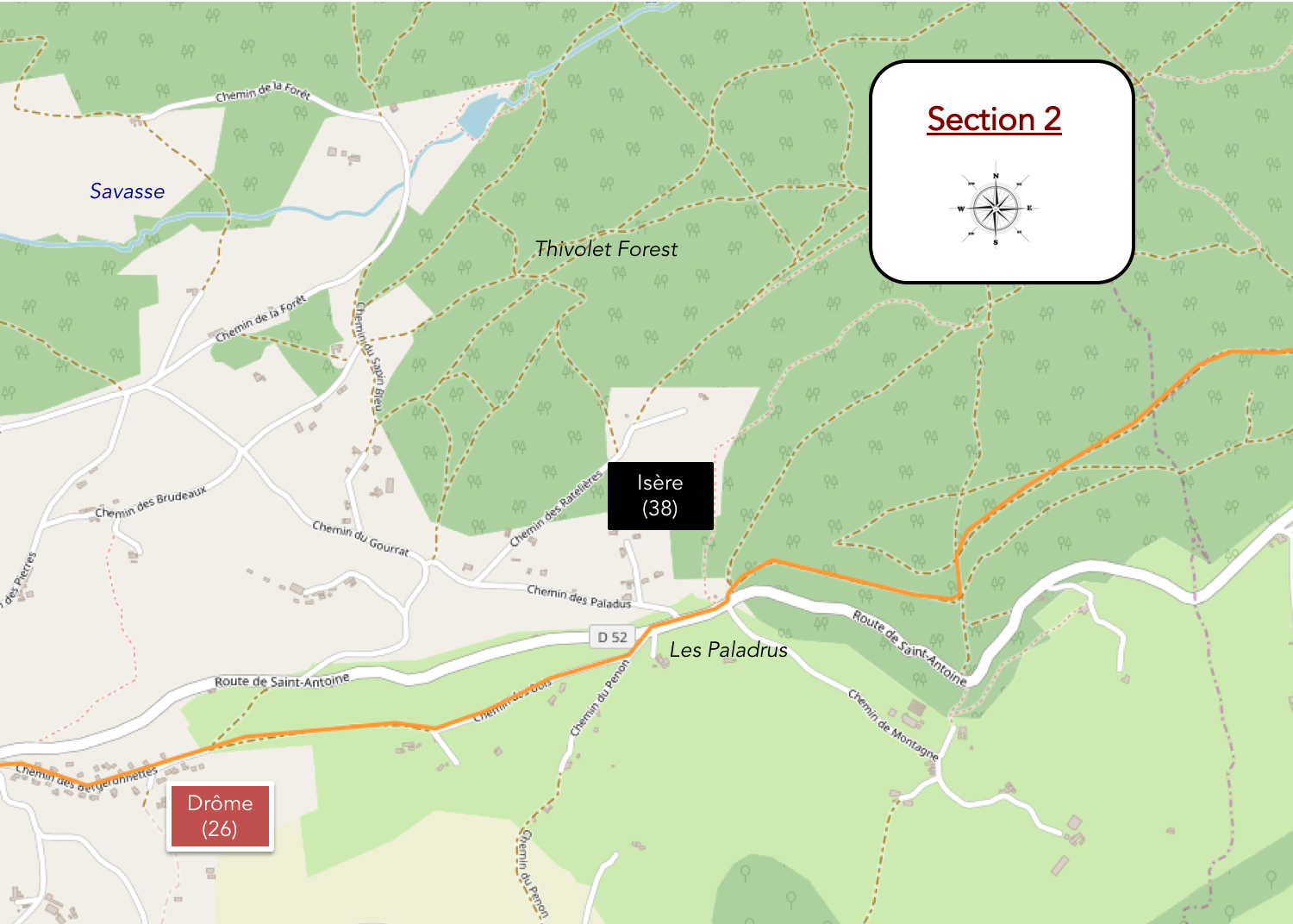

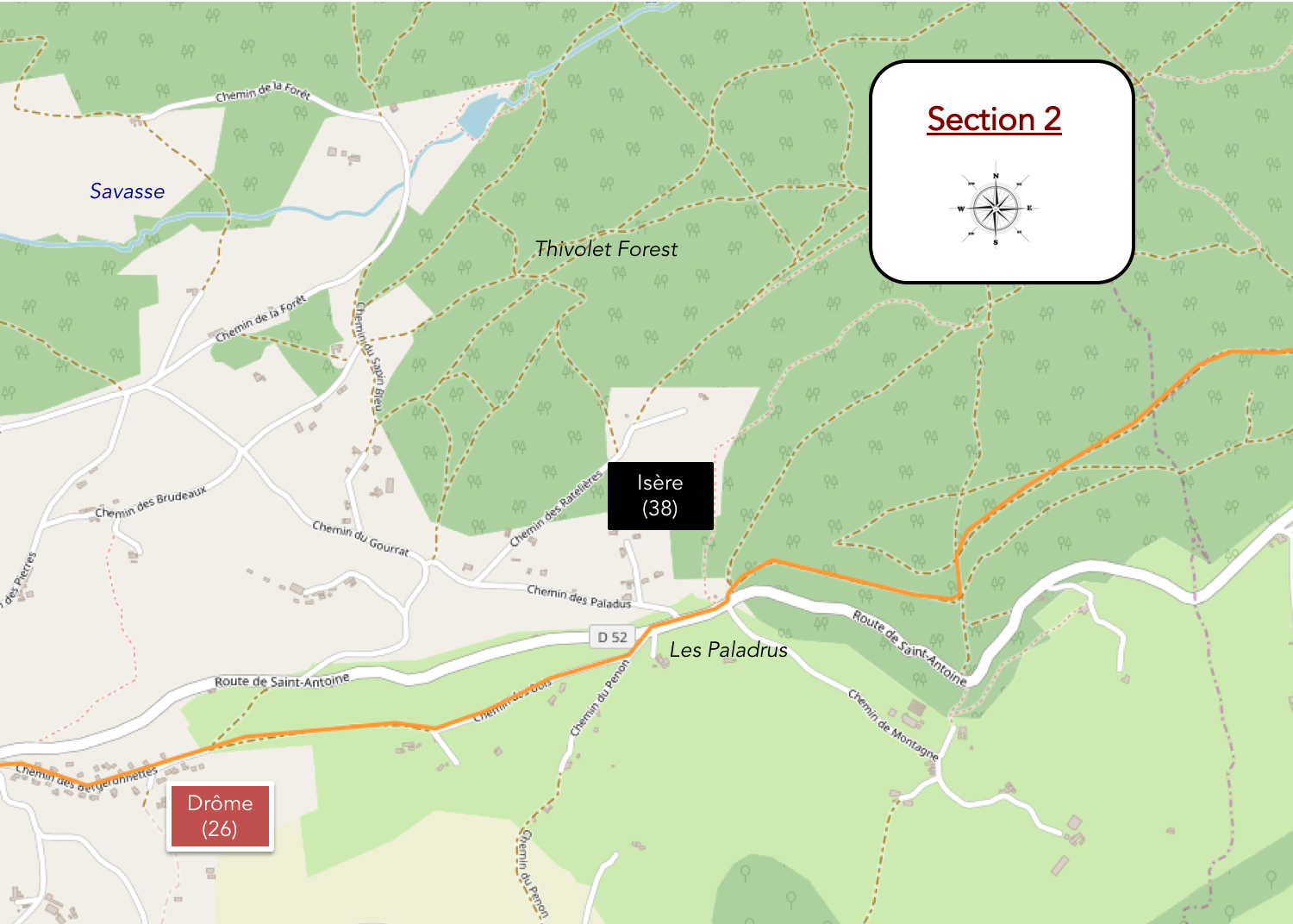

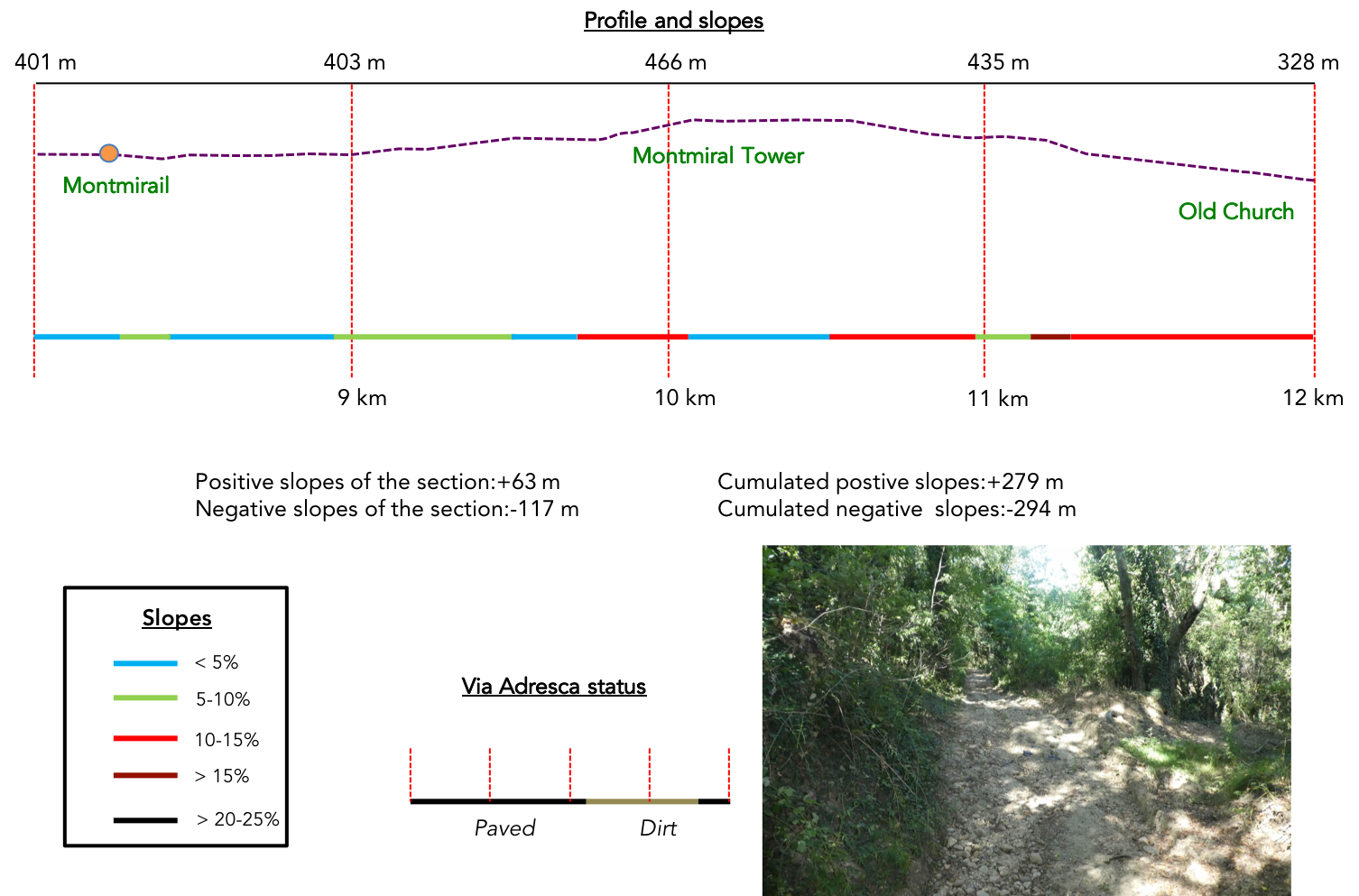

Section 2: In the vast and long Thivolet Forest

Overview of the route’s challengess: A descent with no particular difficulties.

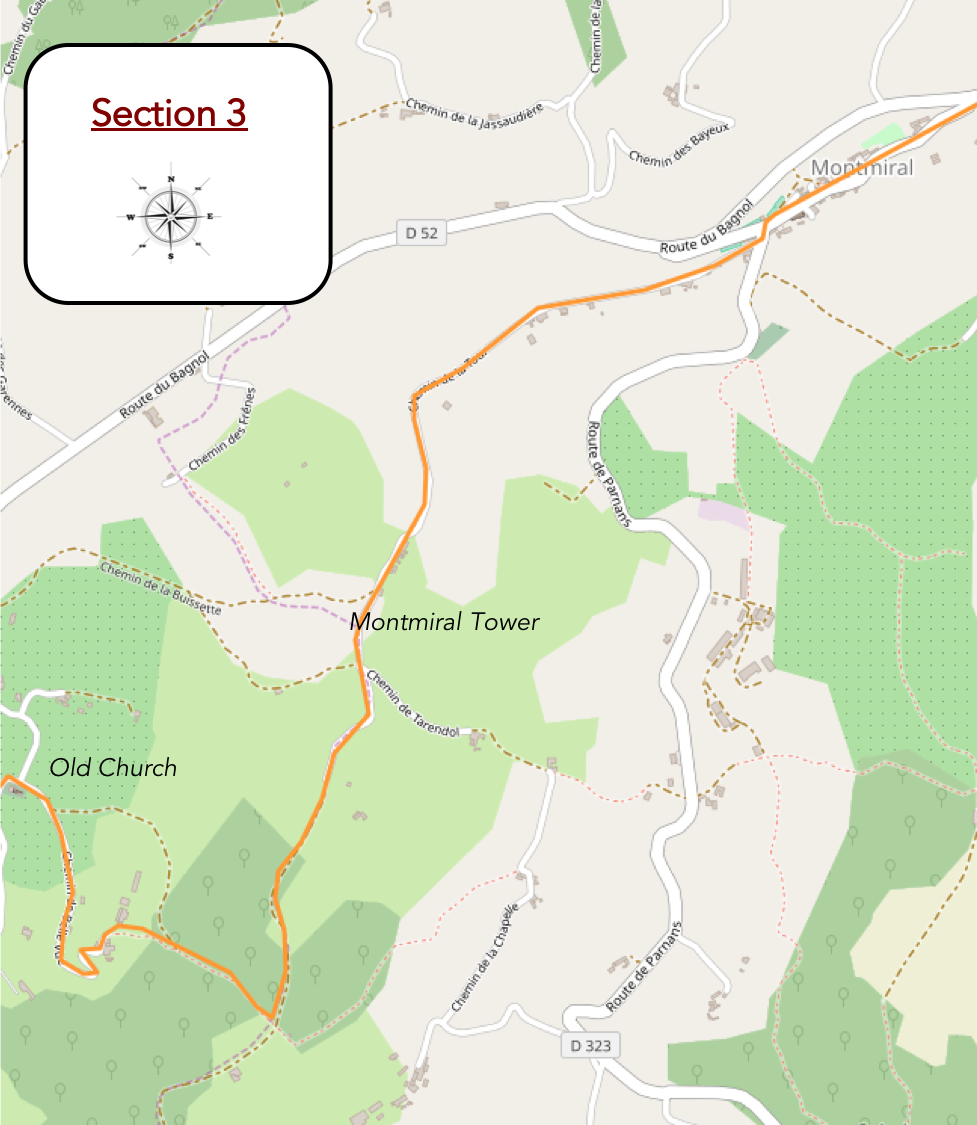

| The path plunges once again into the forest, as if swallowed by a dense and omnipresent shadow. Here, chestnut trees reign supreme, creating a labyrinth of twisted trunks and interwoven branches. The light, filtered through this leafy canopy, diminishes with every step, lending the scene an almost oppressive character. These wild clusters of chestnut trees, standing like sentinels, stifle any sense of perspective, enclosing the traveler in a solitary woodland experience. |

|

|

| Fortunately, the path is well-marked, which proves essential. The trails in this sprawling forest are numerous, making it easy to lose one’s way. Signposts dot the route, especially for those who might, in a moment of distraction, miss the access to the Fontfroide cabins, tucked away from the main path. |

|

|

| The Thivolet Forest, despite its historical significance, is not particularly enchanting here. It is a wild expanse, a tangled web of vegetation where the Savasse river has its source, but it lacks the splendor that characterizes other Chambaran forests. Chestnut trees proliferate, creating a haven for wild boars, which no doubt wallow freely in the clay bogs. It is said that King Francis I, an avid hunter, found joy in this forest. And one can see why: these damp, dark woodlands seem tailor-made for royal hunts. |

|

|

| Further downhill, as the dimness intensifies, the scenery does little to charm. The trunks of the chestnut trees grow dull, their vitality muted by the grayish clay soil. The ground, partly bare, gives way to brambles, lush ferns, and wild grasses, signs of the constant dampness that permeates this area. A few green oaks make a timid appearance, offering rare moments of diversity along this stretch of the Camino de Santiago. |

|

|

| Some forests seem capable of awakening the soul, of igniting the imagination. This is not one of them. The Thivolet Forest, in this section, oppresses more than it inspires. Even the clearings, theoretically havens of light, struggle to break the monotony of clay and dense undergrowth that obscure the sky. Perhaps this somber mood stems from a cruel contrast: just yesterday, the sublime forests of Chambaran offered their sun-drenched treetops and vibrant earth. Today, everything feels drab, weighed down by the descent. |

|

|

Finally, the forest’s last meters stretch on endlessly. Wild grasses overtake the path, tangling with the ruts left by footsteps and wheels. Only 700 meters remain before leaving this stifling environment to reach the area known as Les Paladrus. Some hikers will arrive there with a sigh of relief, as though escaping an oppressive jungle.

| The path drags on, through ruts and rebellious tufts of grass... |

|

|

| …before finally emerging at Les Paladrus. Here, the trail meets the departmental road D52, which stretches across the valley toward St Michel-sur-Savasse and further still to Mours-St-Eusèbe. This junction also brings you relatively close to Montmirail, about two kilometers away. A transition, perhaps, but not yet a destination. |

|

|

| The Via Adresca crosses the departmental road, acting as a bridge between two worlds, and turns toward a gentle, soothing hill. The scenery transforms suddenly, breaking away from the wild tangle of undergrowth. Here, nature seems to have found its harmony: a gently undulating hill dotted with open meadows and groves, bathed in light that invites contemplation. |

|

|

| Soon, you reach the place known as Le Penon, where the road stretches calmly, as if tired of its own twists and turns, and disappears into a welcoming woodland. This passage also marks an invisible yet significant boundary: leaving Isère and entering Drôme, the Drôme of rolling hills that lives up to its name. In this part of Drôme, the geography continues the patterns of Isère: steep valleys and high plateaus, the famous feytas, where moraine rock unfolds its collection of rounded pebbles, fossilized witnesses of ancient glaciers. Prepare to encounter these smooth, round stones, as the ground is generously scattered with them, almost provocatively so. |

|

|

| The woods gradually reclaim the path, enveloping it under a dense canopy of leaves. The foliage filters the light into a dance of shifting shadows, creating an atmosphere of serenity. Here, the trail winds through a more understated natural setting, where each step seems to awaken the rustle of hidden wildlife. |

|

|

| After crossing this wooded enclave, the path opens onto a patchwork of scattered countryside before the paved road reappears, almost timidly, as you near the first houses of Montmirail. This gradual transition from forest to village invites you to slow down, to absorb the tranquil charm of the surroundings before returning to civilization. |

|

|

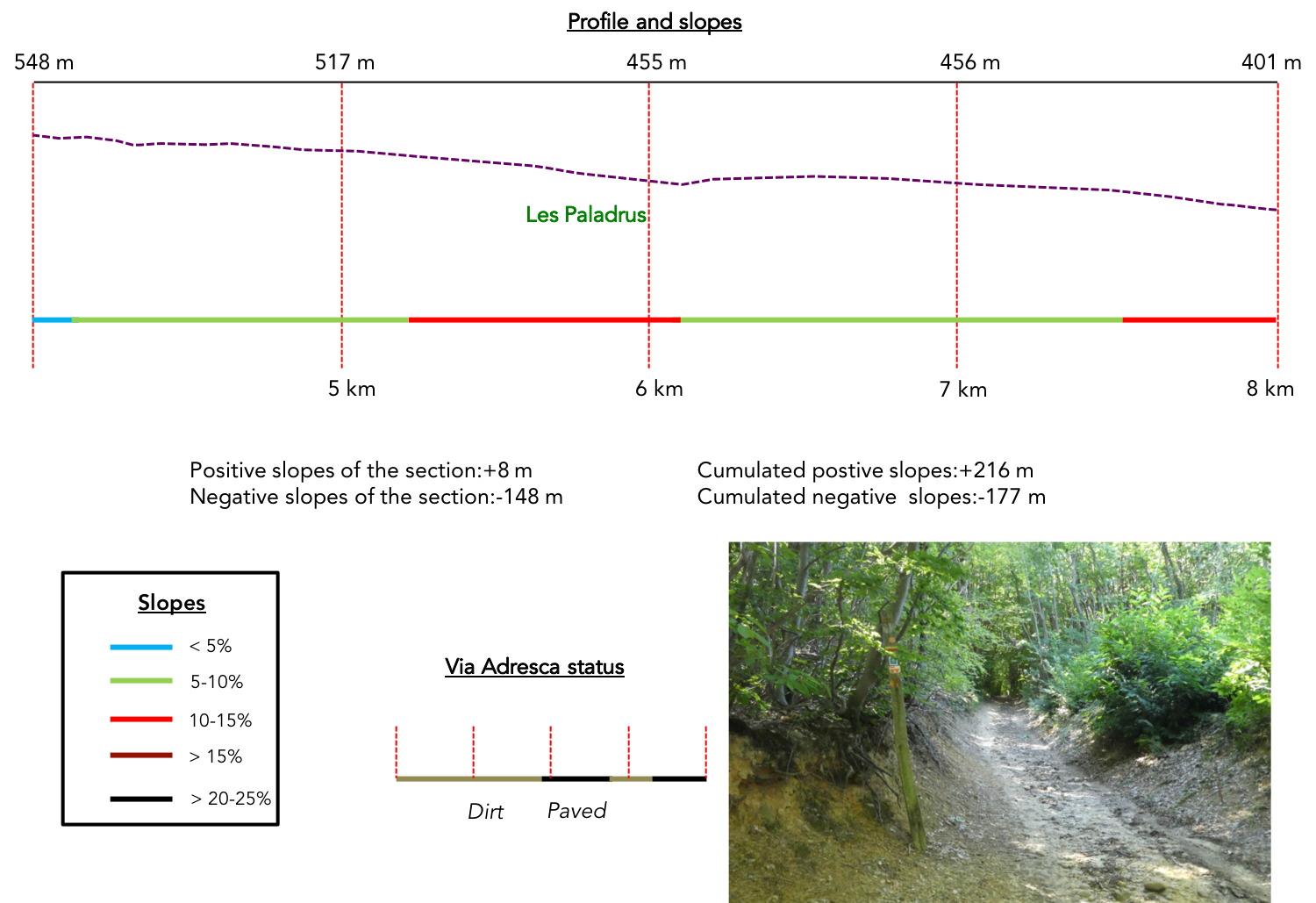

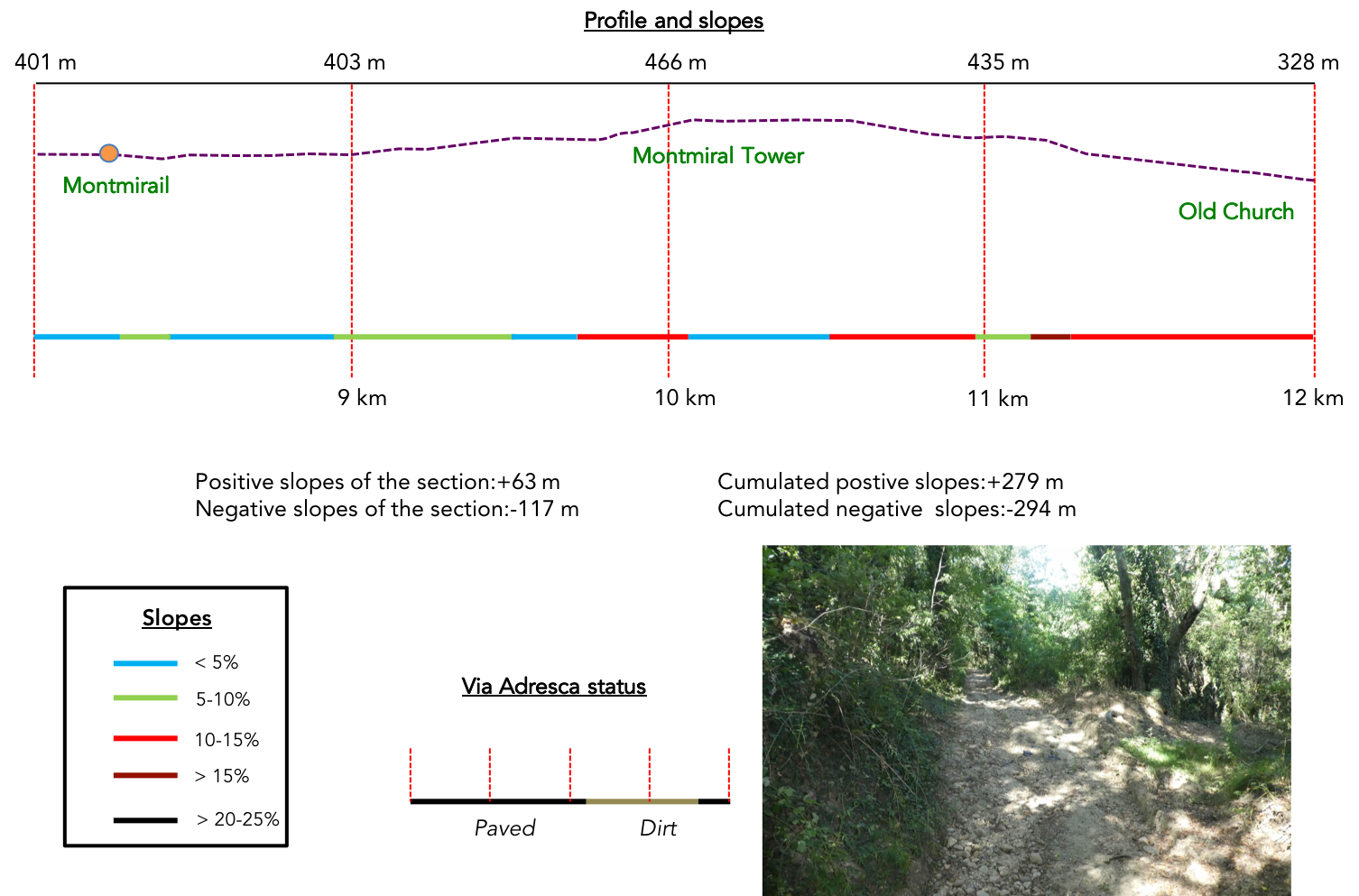

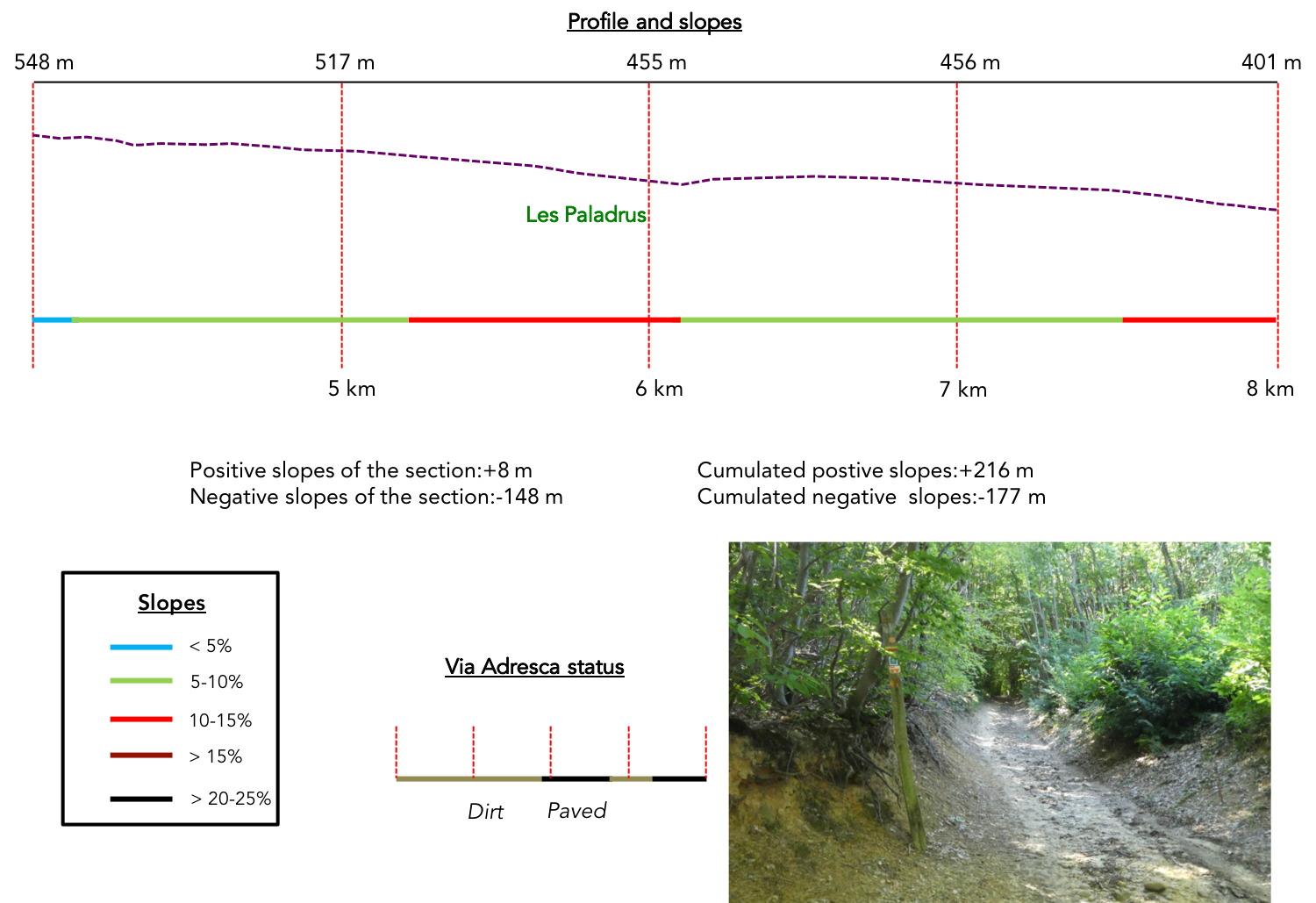

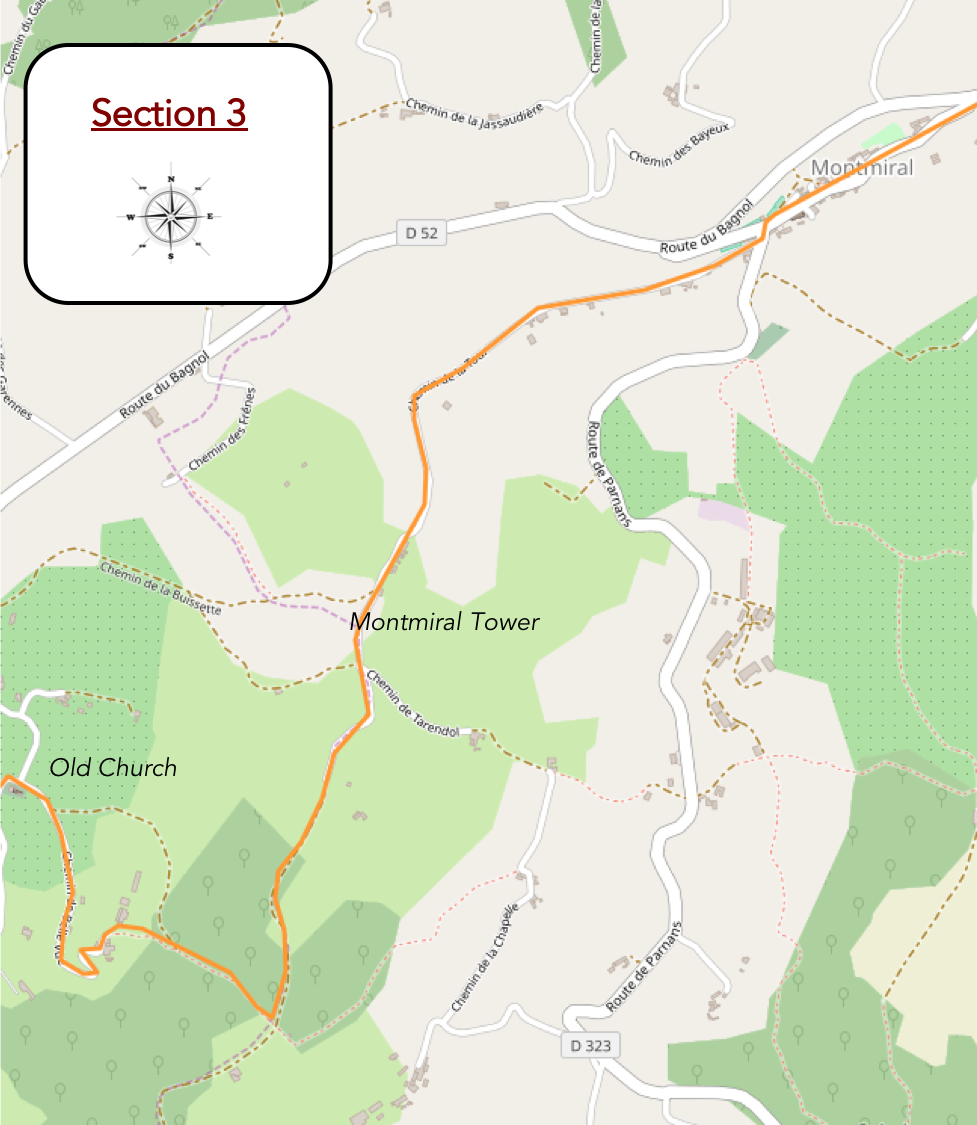

Section 3: From ruin to ruin near St Michel-sur-Savasse

Overview of the route’s challenges: A slightly steeper slope near the Montmirail Tower, followed by a very tricky route heading back down to St Michel-sur-Savasse.

| Montmirail, once a bustling village, has gradually been abandoned, now home to only about 600 souls. A tranquil atmosphere pervades its narrow streets, dominated by Saint-Christophe Church, whose squat bell tower and modest apse stand as sentinels of time, dating back to the 12th century. These ancient stones still whisper forgotten tales, silent witnesses to the passing centuries. |

|

|

| When you reach the heart of Montmirail, after passing the church, particular vigilance is required. The Via Adresca signs, adorned with their iconic scallop shell, almost fade into the scenery. If your gaze falters, you might unintentionally end up on the paved road to St Michel-sur-Savasse. At the corner of the community hall, a shy scallop shell is affixed, so discreet it’s nearly invisible to an inattentive eye. Here, you must become a detective, sniffing out clues. At this precise point, the Via Adresca abruptly turns at a right angle, launching itself up the hill. |

|

|

| A small paved road, named Chemin de la Tour, begins in the village, ascending with quiet confidence toward the Tour de Montmirail, a remnant perched at the summit. |

|

|

| The tower, visible fairly quickly as you climb, remains distant. Like a far-off promise, it looms on the hill but does not draw nearer as quickly as one might hope. |

|

|

| As you climb the slope, the road skirts a half-abandoned hamlet. The stone houses, though partially in ruins, exude a solemn dignity. These buildings, relics of another era, provoke bittersweet reflections: what could still be salvaged from these homes once brimming with life? The paved road, though gentle, is relentless in its steadiness, winding through ash trees, evergreen oaks, and chestnuts. The slope, never exceeding 15%, demands effort but is not brutal. |

|

|

Almost at the summit, the paved road reaches the place known as Montmirail Tower. Below, the village of Montmirail stretches out, sheltered by the majestic shadow of the Thivolet Forest, while in the distance, wind turbines rise with their white blades, adding a modern touch to this timeless panorama.

| The path continues, circling the hill on a dirt path scattered with rocks. The tower, a forlorn remnant, stands apart, left to its fate. Now in ruins, it seems to forget the world, perched on its solitary promontory. |

|

|

| At the summit, an entirely different landscape unfolds before you. The steppes dominate, vast and open, and the view expands toward the rolling hills of the Drôme. On the horizon, the jagged ridges of the Vercors and the mountains of Isère carve a powerful line, like a masterful canvas painted by nature. |

|

|

| Descending the other side is done on a rocky, unforgiving path. The surrounding fields, strewn with stones, tell of the land’s harshness. Farmers, perhaps resigned, have not undertaken the monumental task of clearing this hostile soil. Why bother? The effort would be immense, and the fields, as they are, tell their own story of toughness and resilience. |

|

|

| On the scree, the path, if it can still be called that, hesitantly begins a descent, skirting the edge of oak and chestnut woodlands. Round pebbles willingly nestle underfoot, offering an unexpected yet treacherous caress to your ankles. The slope, for now, remains gentle, a mere prelude to fiercer inclines. |

|

|

| Further down, as if by magic, the path softens, winding peacefully in the shade of a benevolent woodland. Here, the stones seem to have vanished, as if carried away by some enchantment. The light filtered through the foliage provides respite, a generous oasis of shade in this rugged terrain. |

|

|

| But the magic quickly fades, replaced by deep ruts, true scars left by tractors in heavy, almost clay-like soil. These trenches mark the ground with a brutal, unavoidable labor. |

|

|

| A clearing then opens, and like an apparition, the village of St Michel-sur-Savasse emerges below, tiny and solitary under the impassive gaze of the hills. Yet the poor path persists, stubbornly descending, scraping the earth with its stones and carving ruts into the untamed, disordered undergrowth. |

|

|

| And further down, the path becomes outright hostile, almost inhospitable. The bushes thicken, wild grasses invade the space, and pebbles roll underfoot, accentuating slopes that now exceed 25%. The landscape becomes a quagmire, a prolonged ordeal where one hopes for only one thing: to reach the end, no matter what. |

|

|

| Finally, at the bottom of the descent, the long-awaited reward appears: a small paved road, flat and passable. It brings a deep, almost triumphant satisfaction, especially in bad weather, when each slippery stone could have turned into a trap. |

|

|

| The paved road continues, soon passing in front of an old church. There, a few scattered ruins mark the former Benedictine priory of St Pierre-de-Sérans, whose history dates back to the 12th century. This church, once proud, was ravaged by Austrian troops during their occupation in the early 19th century. The cemetery that surrounded it was abandoned in 1905, taking with it the memories of the souls it once protected. Today, the site retains a melancholic beauty, almost unreal. An abandoned house, clumsily attached to the church, defies the passage of time. Perhaps this is what makes these places so poignant: their beauty, amplified by decline, a lingering soul, a witness to bygone eras. |

|

|

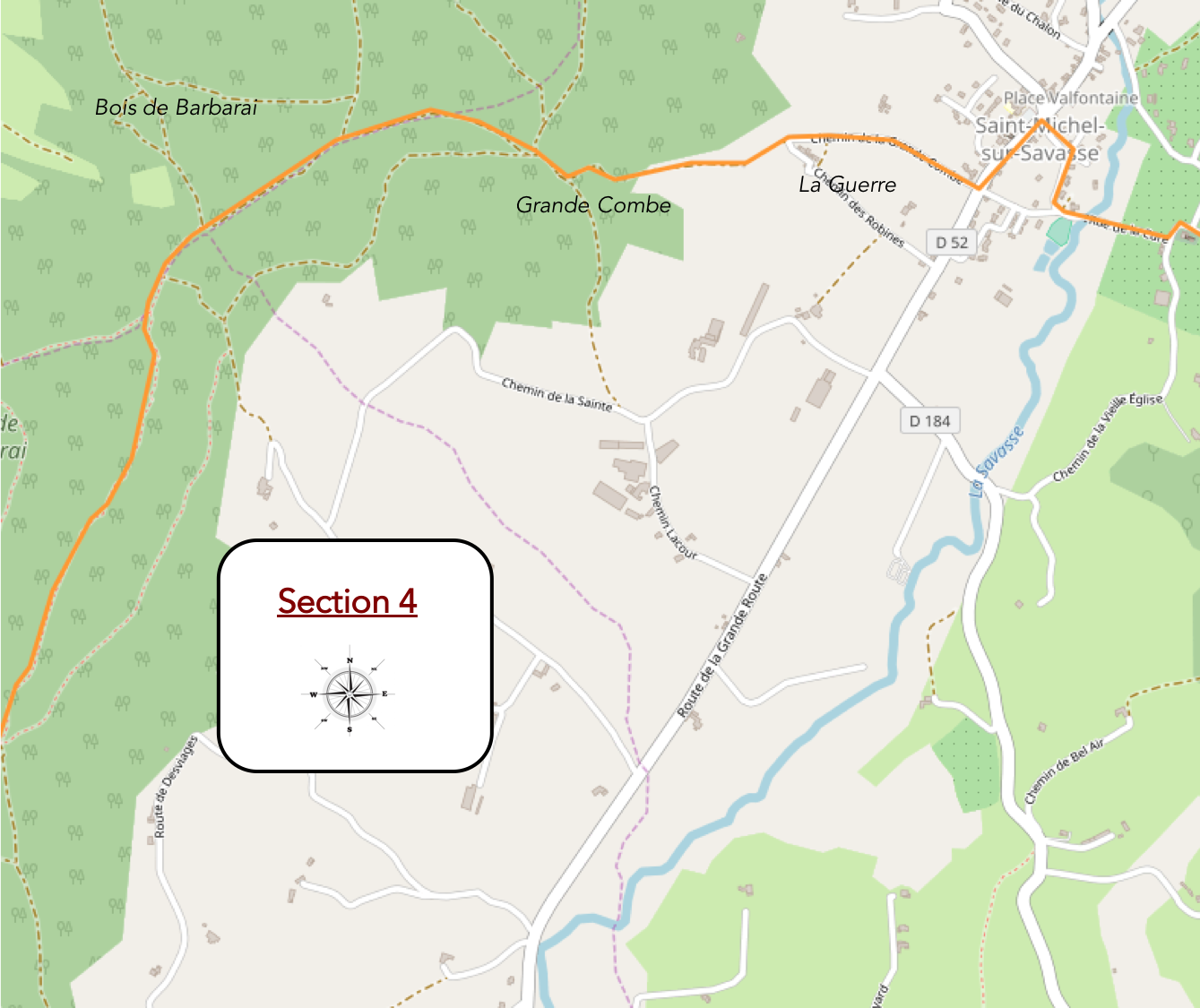

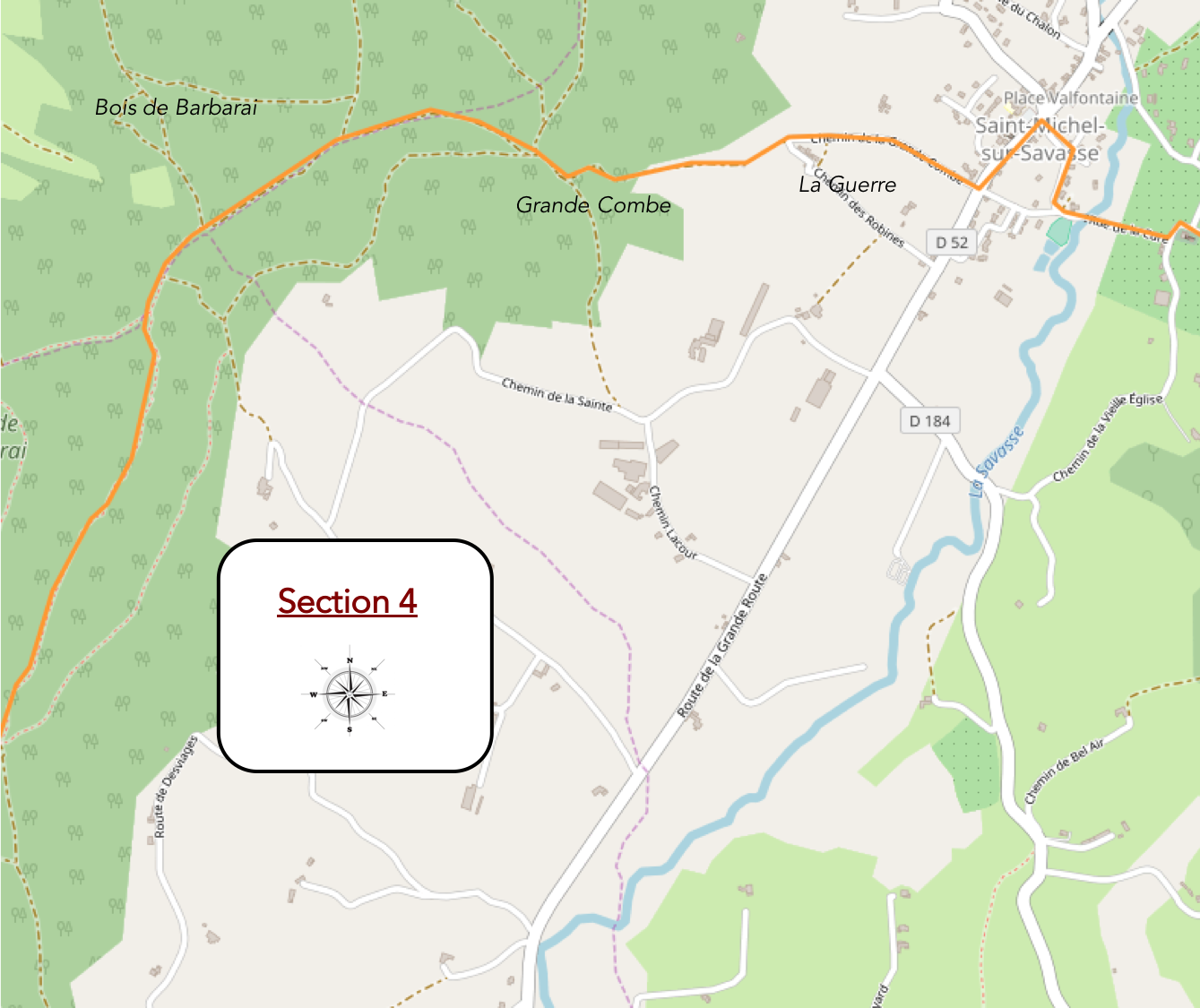

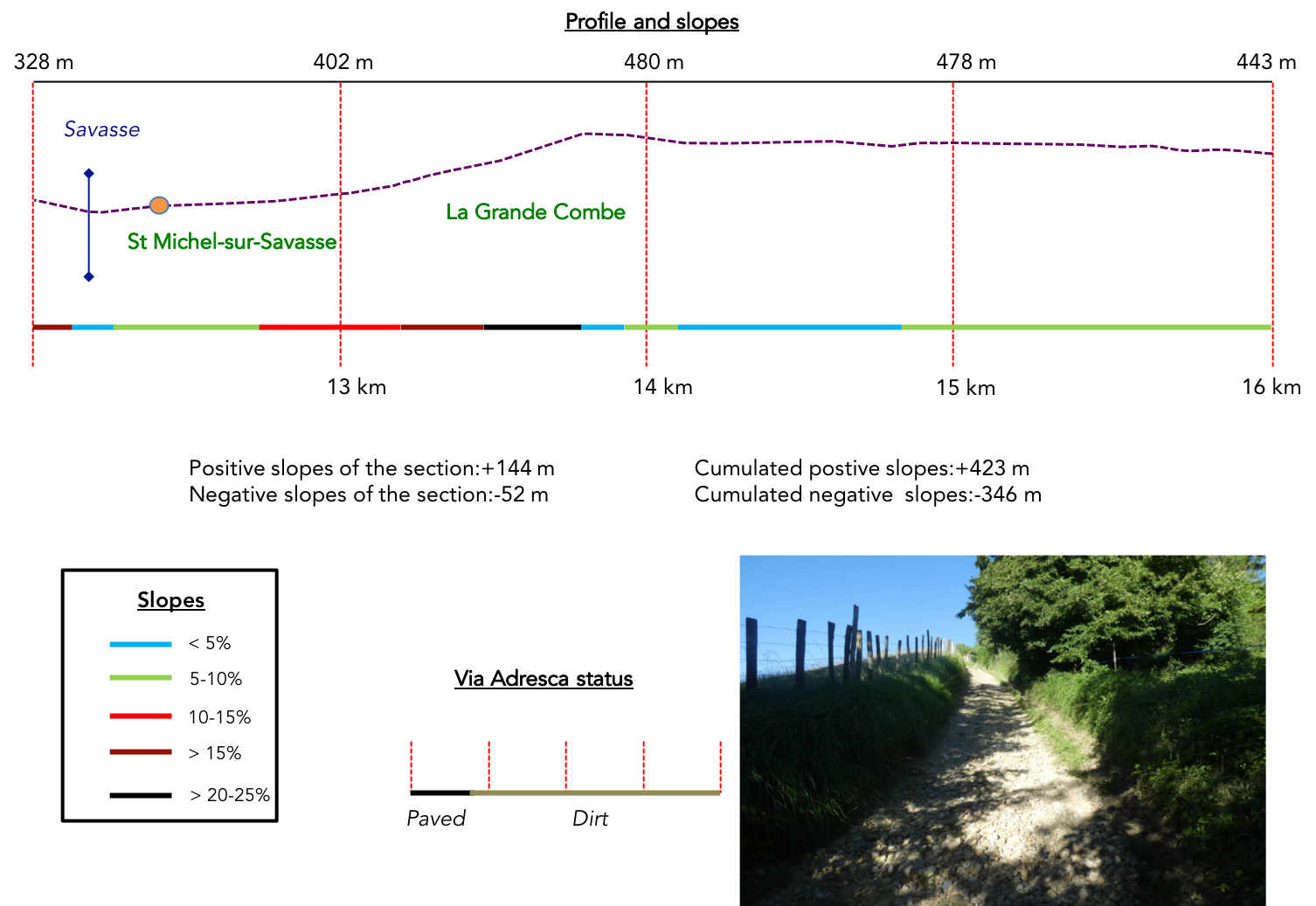

Section 4: On the route to « La Guerre » and beyond…

Overview of the route’s challenges: A grueling climb of nearly 1 kilometer on loose pebbles, with inclines sometimes exceeding 30%, followed by a well-deserved respite in the forest.

| The paved road gently slips away from the Old Church, threading its way between stately walnut trees and humble fruit trees that line the fields. Their foliage forms a sparse canopy, offering glimpses of the sky. |

|

|

| It then curves to cross the Savasse, a modestly proud river. This waterway, often reduced to a mere trickle, carves a quiet melancholy into its dry bed before surrendering to the slope and climbing back toward the heart of the village. |

|

|

| The Via Adresca reaches St Michel-sur-Savasse, a peaceful hamlet of about 600 souls. Its modern church architecture provides a somewhat jarring contrast to the ancient mood of the area. Here, you symbolically reach the midpoint of this long and demanding stage, like a breath caught before the effort.

Let us offer some advice: If you happen to walk this stage in bad weather, avoid the route via the Montmirail Tower and its dreadful paths. Instead, you can simply follow the quiet road from Montmirail to St Michel-sur-Savasse for about 2 kilometers. |

|

|

| At the edge of the village, a paved road breaks away from the departmental road D52, climbing toward a curiously named place, La Guerre (The War), via the Chemin de la Grande Combe. There is no hostility here, except that of the incline. The asphalt stretches obediently amidst walnut and fruit trees, but sharp eyes will notice piles of pebbles along the roadside, a sign of land cultivated by the tractors of walnut and chestnut farmers. |

|

|

At first deceptively easy, the climb quickly turns into a true ordeal. A break in the slope reveals a spectacular rockslide, as if the hill itself had shaken off its mineral mantle. Here, inclines exceed 30%, and every step slides on the unstable ground. The struggle is real and unforgiving. The name « La Guerre » evokes a battle of body and willpower. On the edges, you search in vain for gentler passages. But they are rare, these islands of reprieve.

In rainy weather, this path becomes a hostile arena, where every stone turns traitor. But under a clear sky, the raw, mineral beauty of the place asserts itself, enhanced by a solitary, majestic ruin that amplifies the sense of a setting outside of time.

| For hikers accustomed to Alpine scree, this ascent can be tamed without much difficulty. But for retired walkers on the Way of Saint James, often less prepared for such challenges, every step becomes a trial, and every stone an adversary. |

|

|

| At times, the incline softens, almost as an illusion, only to rise again with renewed vigor, plunging the walker into a dense, almost primeval forest. The atmosphere hums, enchanting and oppressive, as if the trees themselves were whispering incantations to the wind. |

|

|

Finally, deliverance has a name: La Côte Velay. This place marks the end of the relentless climb. Over 1.5 kilometers, you will have ascended 133 meters, rising from 337 to 470 meters in altitude. A trifle for seasoned mountaineers, but for others, each meter feels like a small victory.

| From here, your steps lead to the heights of the « feytas », high plateaus where the generally gentle paths provide a welcome reprieve. Here, the pebbles seem to have disappeared as if by magic, not through human effort but by nature’s patient work. On this austere, dark land, largely devoid of wealth, stretches a true chestnut grove. The tightly packed trunks, like sentinels, cast dense shadows, immersing the gray soil in a twilight glow where everything breathes restraint. |

|

|

| Further on, you reach a place known as Bellefont, and the landscape begins to transform subtly. The forest, once almost oppressive, opens to greater diversity. Chestnut trees remain dominant but yield in places to mighty oaks, majestic pines, and delicate maples. The softened ground becomes a more welcoming companion, absorbing footsteps with unexpected suppleness. |

|

|

| Though this forest feels unified, humans like to assign evocative names to tame these wild places. You are now heading toward the Bois Brûlé, a unique spot where nature seems to waver between harshness and fragility. The ground is compact, almost hostile, a blend of ochre and gray clay, impermeable to water. Even after days of sunshine, large puddles remain in the ruts, sometimes swelling into true ponds that must be carefully skirted. The chestnut trees seem to thrive in this chaotic wetness, their roots stubbornly seeking sustenance. |

|

|

| When you finally reach the Bois Brûlé, the forest begins to gradually fade. Two kilometers of walking still separate you from the Tournu Cross, where the trees finally give way to more open landscapes, like a horizon unfolding after the confinement of the undergrowth. |

|

|

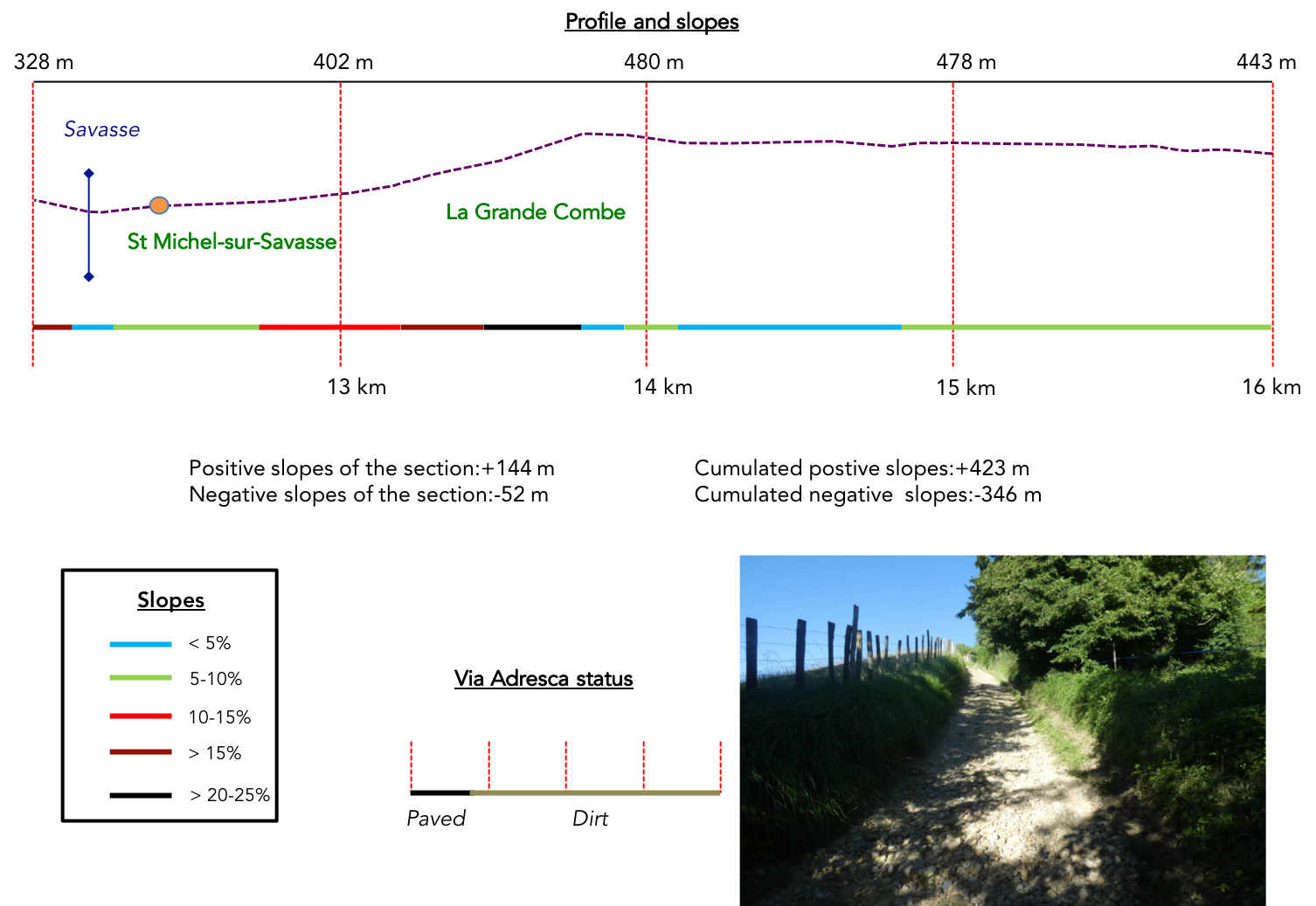

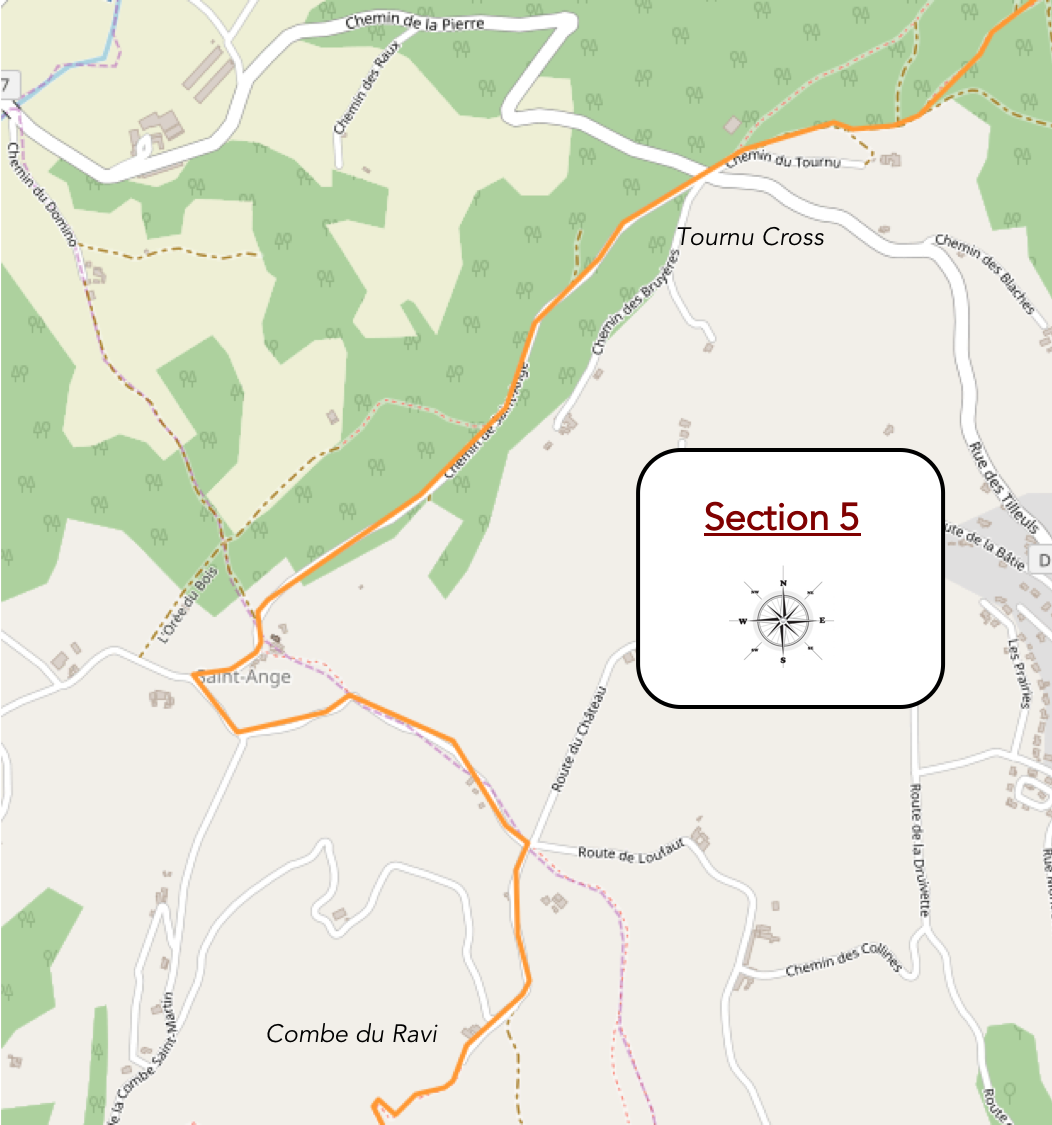

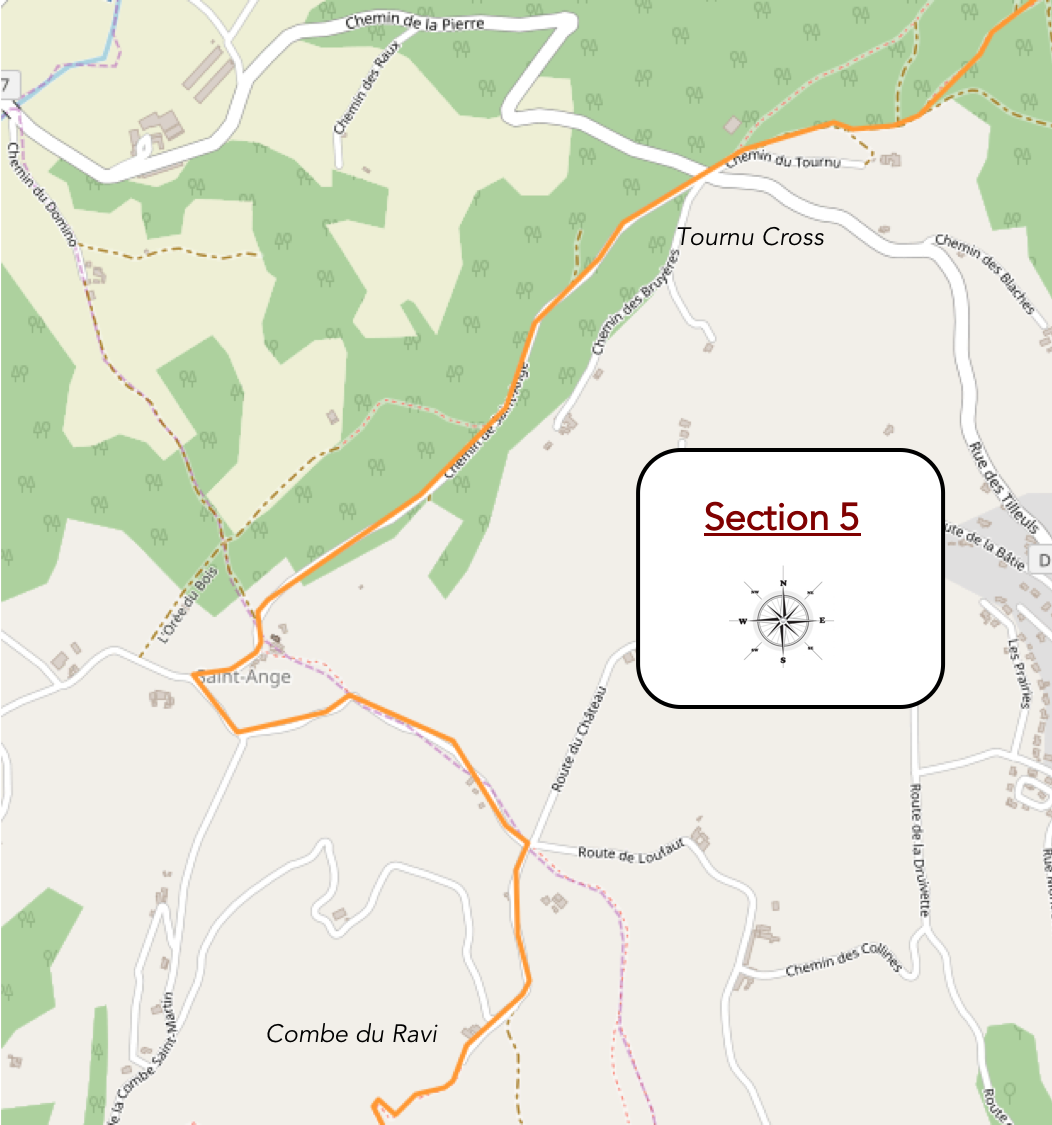

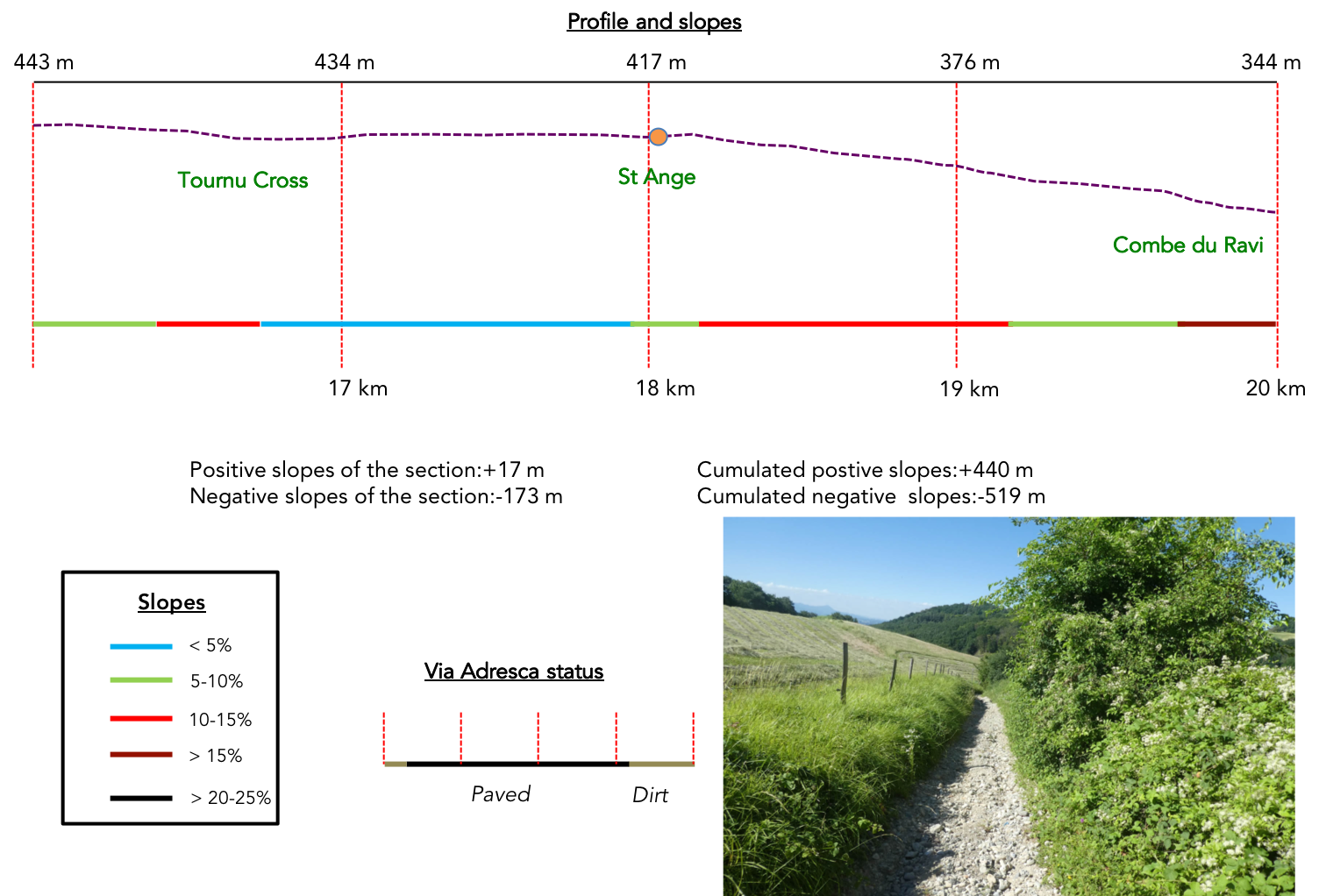

Section 5: On the way to a « lovely » canyon canyon

Overview of the route’s challenges: A relatively easy descent to the Combe du Ravi, though the real test lies not in the incline but in the terrain’s condition.

| As you traverse the forest, the scene seems almost unchanging: stagnant puddles collect in the ruts carved by old carts or modern tractors. The dense, heavy gray soil feels imbued with an ancient memory. The chestnut trees, thin and twisted, appear locked in a silent struggle against this unyielding ground. Among them, a few grand sessile oaks rise majestically, like sentinels of a bygone era. Evergreen oaks mingle in the mix, joined occasionally by rare pines or shy maples that seem hesitant to assert themselves in this shadowy world. |

|

|

| Suddenly, the path offers a brief change: a scattering of loose pebbles serves as a reminder of the timeless, unrelenting force of geology. Here, the slope eases, a mere jest compared to the demanding climb of La Guerre. |

|

|

| Emerging from the forest, the path allows light to pour in beneath the towering oaks, unveiling a breathtaking panorama. The rolling hills of the Drôme Department stretch gracefully, descending toward the expansive Isère plain. In the distance, the Vercors massif looms, immovable and bathed in a golden glow beneath the sun’s rays. |

|

|

| After this moment of natural splendor, the path playfully weaves through cereal fields. But it doesn’t linger long, soon climbing back through thickets where wild vegetation reclaims its dominance. Here, the soil turns almost sandy, a deceptive surface hiding pebbles in the shadows, waiting to trip the unwary hiker. |

|

|

| A brief ascent, little more than a ripple in the terrain, leads at last to the Tournu Cross. This elegant iron cross, standing proud amidst the countryside, extends its arms toward an open horizon, inviting rest and reflection. |

|

|

| At this point, the Via Adresca adopts a gentler tone. It meanders peacefully toward Sainte-Ange, following a 1.6-kilometer paved road devoid of traffic. Beneath the sheltering shade of tall broadleaf trees, the path feels almost meditative. |

|

|

| The road winds through a tapestry of contrasts: open woods and denser forests where tightly packed ash trees and oaks seem locked in a quiet contest with the dominant chestnuts. An imperceptible but genuine botanical rivalry unfolds as each tree vies for a fragment of precious light. |

|

|

| As you near the hamlet of Sainte-Ange, the landscape opens once more. |

|

|

|

| Perched on a hill overlooking the Isère plain and facing the commanding Vercors massif, this site is steeped in history. An ancient Gallo-Roman settlement once stood here. The Romanesque church, built in the 12th century from stone, resembles a fortress from another age. Despite later additions, its sober architecture exudes a quiet dignity. With its unadorned façade, the church demands silent reverence. A listed historic monument, it whispers of a glorious past. Like many rural churches on the Way of Saint James, it remains locked most of the time, opening its doors only for Sundays… or weddings.

The hamlet itself, with its stone houses clinging to the hillside, appears frozen in time. Life here has dwindled; the town hall and rectory are long gone. The church, integrated into the Peyrins parish for over a century, still attracts weddings. The transformed barn, now a wedding venue, merges past and present, creating an enduring charm. |

|

|

| Beneath Saint-Ange, the road snakes through the dense shadows of ancient oaks. Here, fields of oilseeds dominate, particularly rapeseed, whose golden expanses capture sunlight in an almost surreal manner. The golden soil seems to breathe with the rhythm of the wind that gently stirs the stalks. |

|

|

| Descending further, the road meets a crossroads where paths intertwine like threads of a forgotten web. Instinct might tell you to take the rocky trail climbing the hill ahead, but a surprise awaits. That path is blocked, nudging you gently toward an alternative. The organizers of the Via Adresca, always seeking new wonders, have charted a detour that promises to amaze. Anticipation builds and you can almost taste the unexpected. Prepare to be delighted. |

|

|

| The road descends toward Pianières, slipping past scattered homes nestled among fruit trees, their discreet silhouettes blending into the pristine landscape. These residences feel more attuned to the seasons than to human intervention. |

|

|

| Lower down, another crossroads awaits, with a lone rocky path climbing to the heights. But no, that’s not your path. Yours lies straight ahead, leading directly into what seems like a dead end, straight into the unknown. |

|

|

Soon, you find yourself on a narrow trail, a corridor of pebbles that tumbles steeply downward, plunging into the Combe du Ravi (Delighted). The name, almost prophetic, matches the geography of this rugged and untamed place, where nature asserts itself with raw, unfiltered splendor.

| Who would have imagined that just a dozen kilometers from the bustling urban centers of Valence and Romans, home to over 150,000 people, such a natural treasure could exist? The narrow trail, the dizzying slope, all conspire to make this descent a unique experience, a feast for the senses. Solidified pebble masses and deep ruts offer a challenge with every step. The wildness of the place is so profound that it feels as though at any moment, a boar or even a wolf might emerge from the thickets, a ghost of the past brought to life. |

|

|

Section 6: Savasse, a river or a canyon?

Overview of the route’s challenges: route without difficulty.

| At the bottom of the ravine, soft, deep sand suddenly replaces the pebbles, as if, by some unexpected enchantment, you find yourself by the seaside. The atmosphere becomes almost surreal, a landscape oscillating between harshness and softness, where the ground constantly transforms under your feet. Here, the traces left by mountain bikers far outnumber those of ordinary walkers, imprinted in the sand like signs of vibrant life, ever-moving. |

|

|

| The path, unhurriedly, slopes up slightly, still caressed by the fine sand, and meets a small paved road, drowsing under generous canopies. The air seems suspended, the place inviting rest, as if time itself hesitated to move forward under the dome of trees. |

|

|

| The road then crosses a wide plain bordered by woodlands. The earth here breathes deep serenity, a tranquility occasionally disturbed by the wind weaving between the trunks. The dense, sheltering vegetation seems to murmur with each step, almost imperceptibly, an old, forgotten song. |

|

|

| At the end of this plain, fruit trees stand tall, proud and silent, like witnesses to time. You then arrive at a large paved road near the Savasse River, a place marked by the contradiction between its apparent calm and the subterranean violence of the river bearing its name. |

|

|

| he road runs alongside the river, but strangely, no murmur of water breaks the silence. A peculiar calm, almost supernatural. |

|

|

And for good reason: here is the river. You see the Savasse, but you don’t hear it. You don’t feel it. Not a drop of water, just a wide bed of large pebbles, frozen in an almost unsettling stillness. Yet, this dry riverbed is but a fleeting illusion. The Savasse, despite its tranquil appearance, is a true menace, feared for its sudden and devastating floods that, every year, scar the plains of Romans-sur-Isère. If you doubt its violence, a few videos on the internet will reveal the fury of this river when it rages. At the time of our visit, the region had not seen rain for fifteen days, and yet the threat lingered.

| Further downstream, a bridge crosses the river. Here, a thin trickle of water, barely noticeable, winds between the pebbles. But perhaps the water flows unseen beneath the stone bed, invisible yet omnipresent. |

|

|

| From this bridge, the Via Adresca continues its way, nearly flat, along the Chemin des Blaches. The name, like an echo of the past, evokes ancient oak groves, remnants of a bygone era. The earth here turns almost sandy, presenting a small challenge to the feet with each step, a slight effort that is almost pleasant. The Chemin des Blaches is popular with mountain bikers and joggers, especially on weekends, when their numbers attest to the appeal of this nature-filled escape. |

|

|

| The Chemin du Bateau then takes over, and here, sand vies with coarse gravel, offering a striking contrast, vibrant underfoot. The landscape seems to play with the ground’s texture, a small battle between softness and roughness that keeps you adjusting as you move. |

|

|

At the end of the path, the Via Adresca turns at a right angle onto the Rue de Sallmard. A discreet but marked transition, like an invitation to another journey.

| A small paved road then emerges, plunging into a forest that seems to engulf everything in its deep shadows. |

|

|

| Finally, « rue » is somewhat of an exaggeration for this spot, as the road ends in a cul-de-sac, fading into beaten earth, like a forgotten boundary. Then, a true dirt path begins, winding between meadows in a valley of almost perfect gentleness, a haven of peace where nature seems suspended in eternal stillness. |

|

|

Section 7: In the exotic canyons of Mours-St Eusèbe

Overview of the route’s challenges: route without difficulty, featuring light rolling hills until the end of the stage.

| At the end of the small dale, the still rocky path climbs into a dense woodland before emerging onto the Chemin des Grottes. |

|

|

| Here, the adventure takes a radically different turn. The landscape becomes utterly wild, as if challenging human presence. The hill, punctuated by caves and mysterious caverns, seems to breathe an ancient history. Some of these cavities, it is said, date back to the Paleolithic era, bearing witness to a bygone time. But today, the brisk pace of the journey allows little time to explore these legendary sites. |

|

|

| Just a few steps from civilization, you enter a genuine canyon, where the trail often narrows to the point of merging with the vegetation. The path descends, weaving through brambles and wild grasses in a raw world where nature reigns supreme. Though stunningly beautiful, the place doesn’t spare you a few challenges. At times, persistence will be required to find your way among the many paths that snake through the undergrowth. Yet, all these trails, as confusing as they may be, inevitably lead you toward the small town. |

|

|

| The Chambaran pebbles that have accompanied you so far give way to soft, almost caressing sand that gradually covers the ground. Around a bend, you’ll encounter daring mountain bikers racing down the slope and hurried joggers populating the area during the weekend. The crowd seems to multiply in an instant, creating a vibrant microcosm pulsing with the intensity of this nature. At the bottom of the dale, the path widens, perhaps signaling the end of this wild adventure, an almost imperceptible transition to a more orderly world. |

|

|

| The Chemin des Grottes gently leads you toward the outskirts of Mours-St Eusèbe, where the landscape gradually shifts, giving the sense of leaving untamed nature behind for a more domesticated setting. |

|

|

| The now calmer road follows the Chemin des Marronniers, slowly guiding you toward the heart of the place. |

|

|

|

|

| Mours-St Eusèbe, a small town of 3,000 inhabitants, doesn’t boast major attractions. Yet, this locality feels frozen in time, holding within its essence a blend of past and untamed nature. The name Mours, evoking the marshes that once engulfed these lands when the Savasse roared as far as Romans, resonates like a distant memory. The canyon crossing, in particular, stands as a living testament to this landscape’s past, a place shaped by the power and savagery of water. According to legend, the hill once served as a meeting point for witches and early pagans, a tale still whispered in the narrow streets. The church, with its Romanesque bell tower, listed as a historical monument, is a relic of this ancient era. Although altered in the 19th century to include neo-classical elements, it retains part of its Romanesque soul, a subtle fusion of past and present. The Museum of Sacred Art invites visitors to explore this spiritual dimension at a leisurely pace.

As for accommodation, Mours offers no options. It feels more like a tranquil suburb, far from the conveniences of a larger city. The best choice for lodging is to head to Romans-sur-Isère, just two kilometers away. This town of over 30,000 inhabitants offers a much wider range of options while remaining close to the nearly wild nature that defines Mours. |

|

|

Official accommodations on the Via Adresca

- M. Tardy, 1 Impasse des Lavandières, St Michel-sur-Savasse; 04 75 02 96 46; Guestroom, dinner, breakfast

- Gîte la Renaissance, Pont sur la Savasse; 06 16 11 60 91; dinner, breakfast

Pilgrim hospitality/Accueils jacquaires (see introduction)

Along the Via Adresca, accommodation options are often limited. Unlike the touristy areas of southern Ardèche, this route doesn’t offer a wide selection of places to stay. Even options like AirBnB are scarce, and their addresses are often not available. The accommodation list in this guide includes only those located directly along the route or within 1 km of the path. For a more comprehensive overview, the Guide des Amis de Compostelle provides a detailed list of all accommodation addresses, as well as bars, restaurants, and bakeries, even those located several kilometers off the route. One particularly challenging section of the journey is the area around Mours-Saint-Eusèbe, where there is no accommodation available. Pilgrims are advised to plan ahead and seek accommodation in Romans-sur-Isère, a larger town just 2 km away from the route. You can contact the local Tourist Office at +33 (0)4 75 02 28 72 for further information on lodging options. Alternatively, if you prefer to stay closer to the route, you can continue on to Les Balmes, which is located a little farther along the route. Be sure to plan ahead to ensure a comfortable and stress-free stay during this challenging stage of the journey.

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 11: From Mours St-Eusèbe to Roche-de-Glun |

|

|

Back to menu |