A beautiful abbey at the end of the route

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

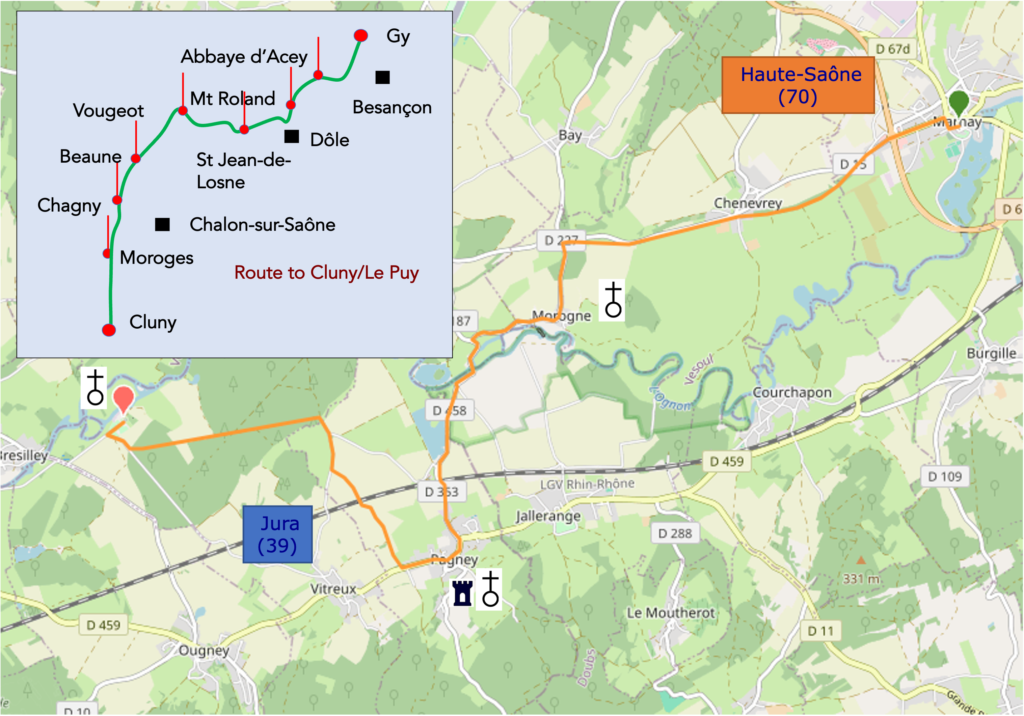

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-marnay-a-labbaye-dacey-par-le-chemin-de-compostelle-218315077

| This is obviously not the case for all pilgrims, who may not feel comfortable reading GPS tracks and routes on a mobile phone, and there are still many places without an Internet connection. For this reason, you can find on Amazon a book that covers this route.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page. |

|

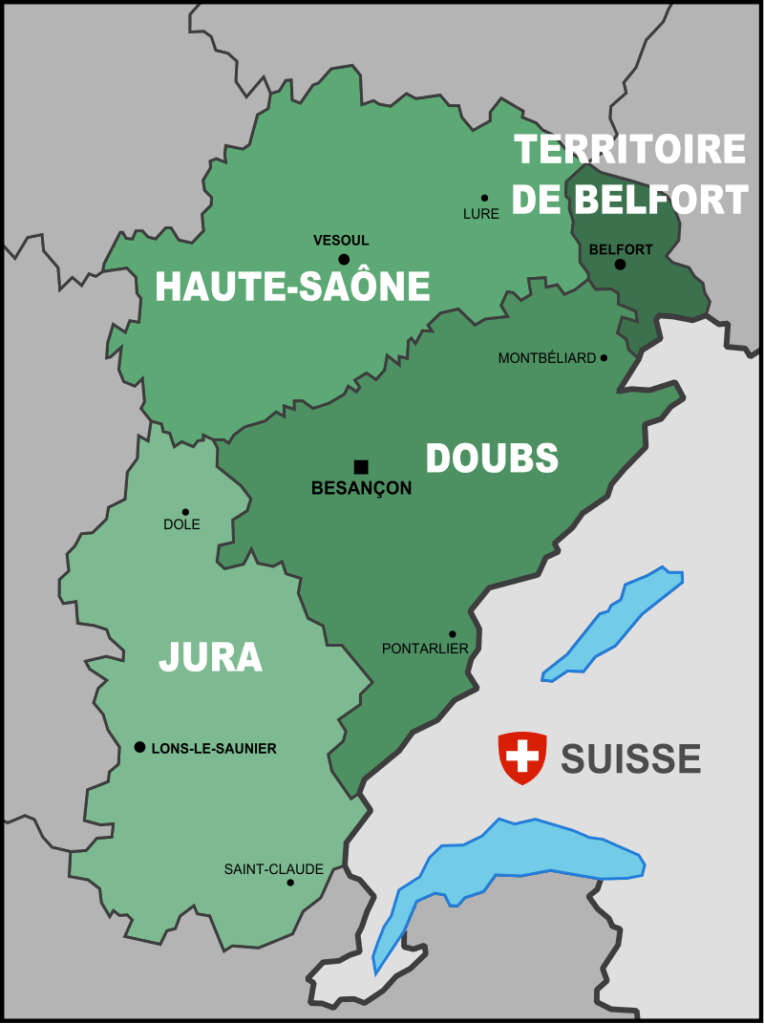

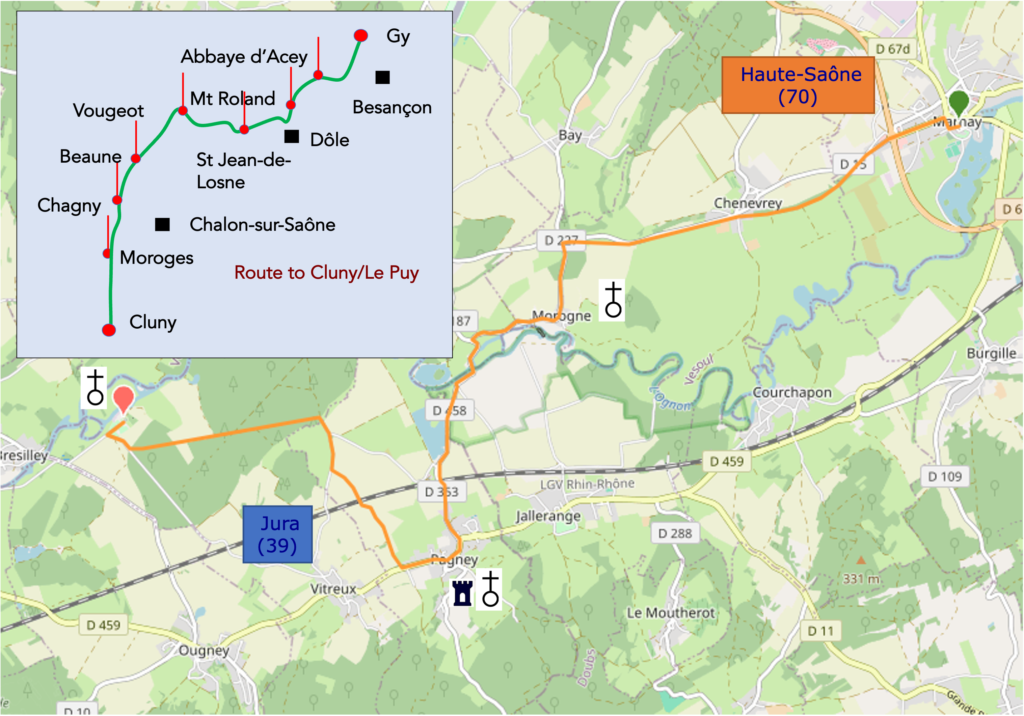

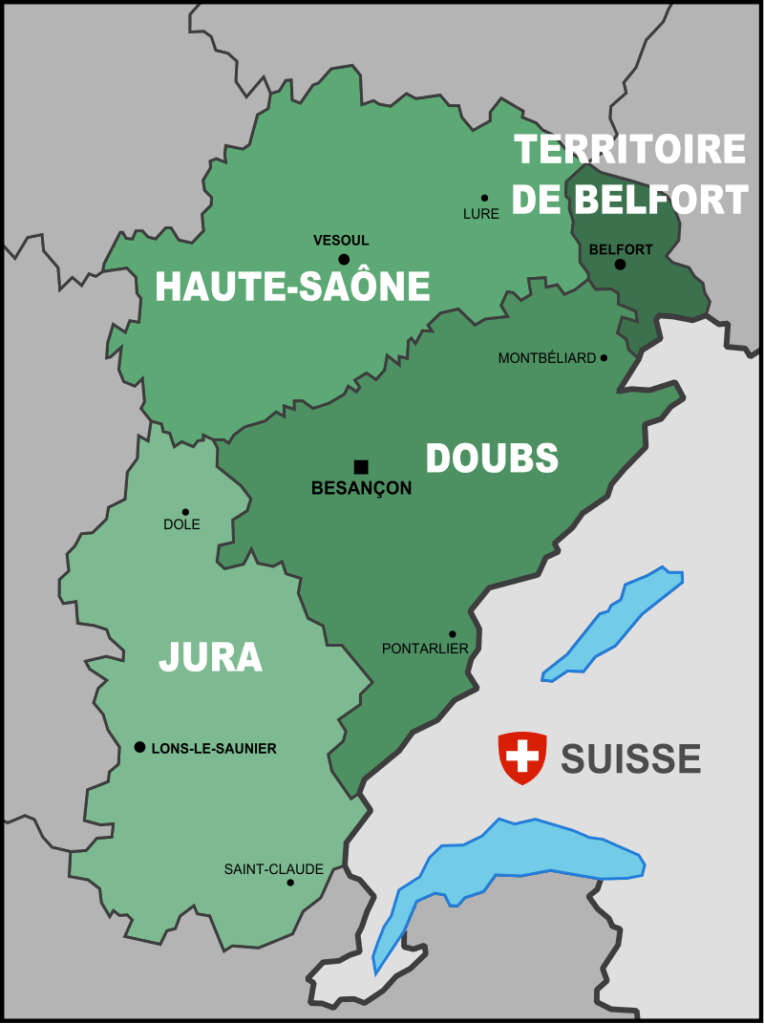

The pilgrim reaches the end of his journey in Haute-Saône. He has crossed much of Franche-Comté, discovering little by little the many faces of this region. Franche-Comté, now integrated into Bourgogne–Franche-Comté, is an ancient province in the east of France. It brings together four departments: the Doubs, the Haute-Saône, the Jura and the Territoire de Belfort. From the Swiss or German border, the route first advanced from the north, crossing the hills of the Territoire de Belfort, before entering deeply into the Haute-Saône, which it crossed from side to side to the south of Vesoul, the departmental capital. The department of the Doubs, with Besançon at its heart, is only brushed by the road to Santiago, which then continues toward the Jura, another emblematic land of the region whose capital is Lons-le-Saunier and which also includes the beautiful town of Dole. Franche-Comté is a land of borders. It touches Switzerland to the east, Burgundy to the west, Lorraine and Alsace to the north. This particular position explains its identity forged by multiple influences, but also by a strong determination for freedom. The very name “free county” evokes this independence jealously guarded over the centuries. Franche-Comté is a land where the rugged relief of the Jura meets beautiful rivers and above all vast plateaus rich in meadows and varied crops. Discreet, it reveals itself to the traveler as a land of contrasts, both harsh and gentle, severe in winter yet generous in landscape. Everywhere, walking reveals an omnipresent forest, among the densest in France. These immense woods give the region a depth and a special serenity.

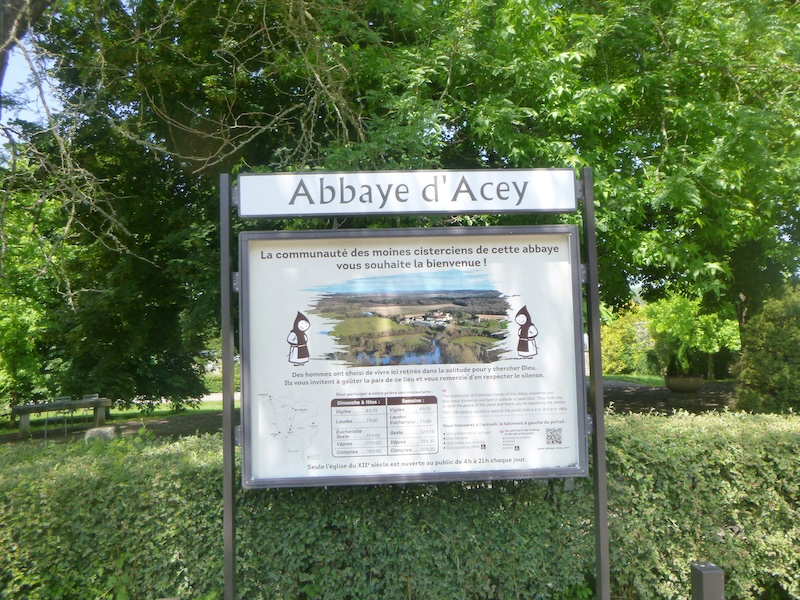

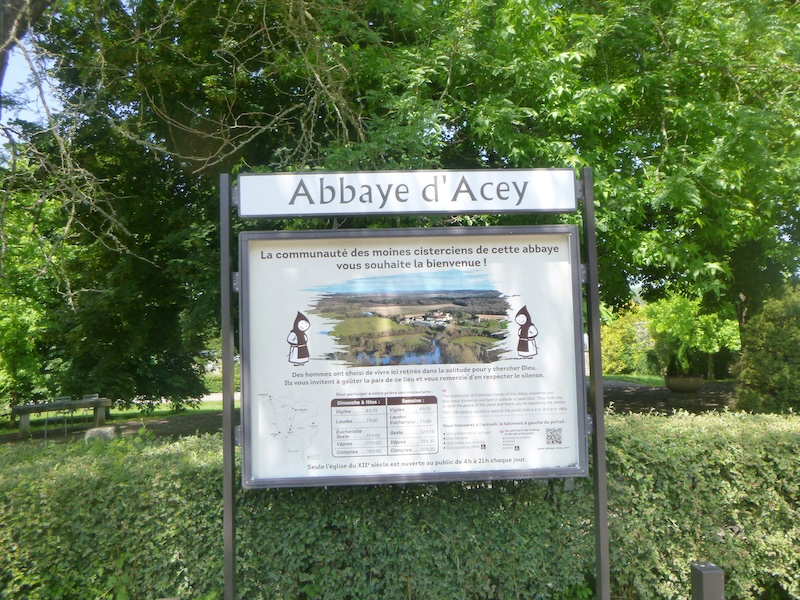

The route of the day ends at the Abbey of Notre-Dame d’Acey. Founded in 1136, this Cistercian abbey is located in the valley of the Ognon Rver, in the north of the Jura department in Franche-Comté, at the boundary of the Haute-Saône and the Doubs, between Dole and Besançon. Today it is inhabited by Cistercian Trappist monks and remains the only Cistercian monastery still occupied by a monastic community in Franche-Comté.

How do pilgrims plan their route? Some imagine that it is enough to follow the waymarking, but you will soon discover that the signs are often lacking. Others use guides available on the Internet, which are also often too basic. Others prefer GPS, provided they have downloaded onto their phone the Compostela maps of the region. By using this method, if you are an expert in GPS navigation, you will not get lost, even if at times the route shown is not exactly the same as the one indicated by the scallop shells, yet you will safely reach the end of the stage. In this respect, the site that can be called the official one is the European route of the Roads to Compostela (https://camino-europe.eu/). For today’s stage the map is correct, although this is not always the case. With a GPS, it is even safer to use the Wikiloc maps that we provide, which describe the signposted route as it actually exists. But not all pilgrims are experts in this type of walking, which for them disfigures the spirit of the path, so you may simply follow us and read us. Every junction of the route that is difficult to interpret has been pointed out to prevent you from losing your way.

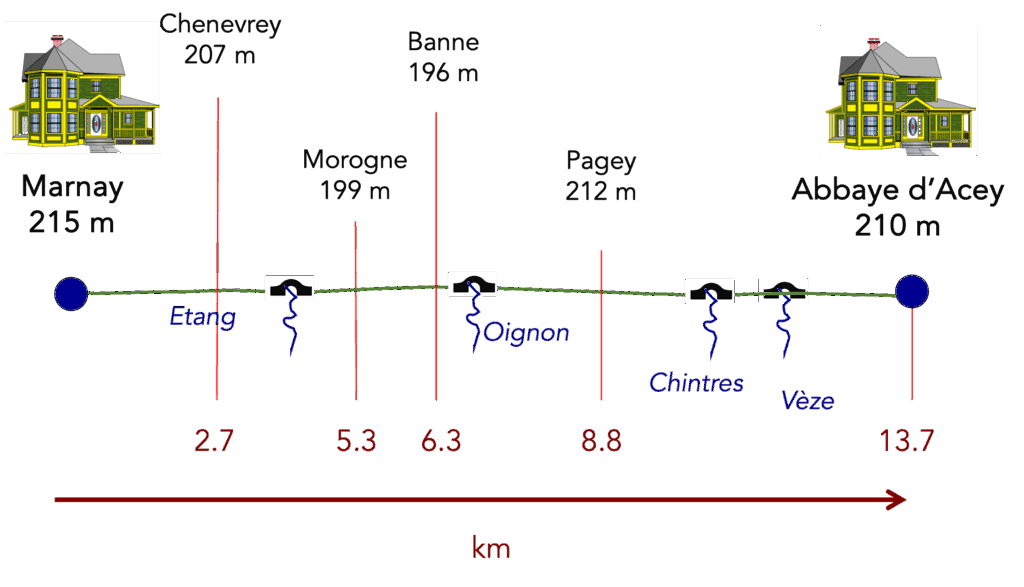

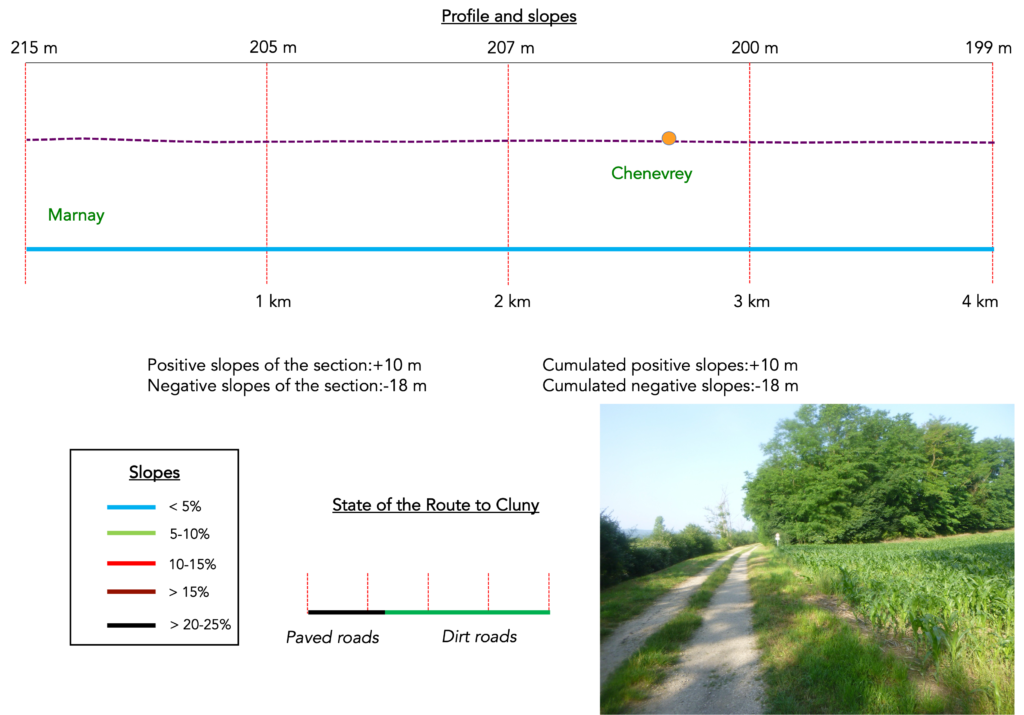

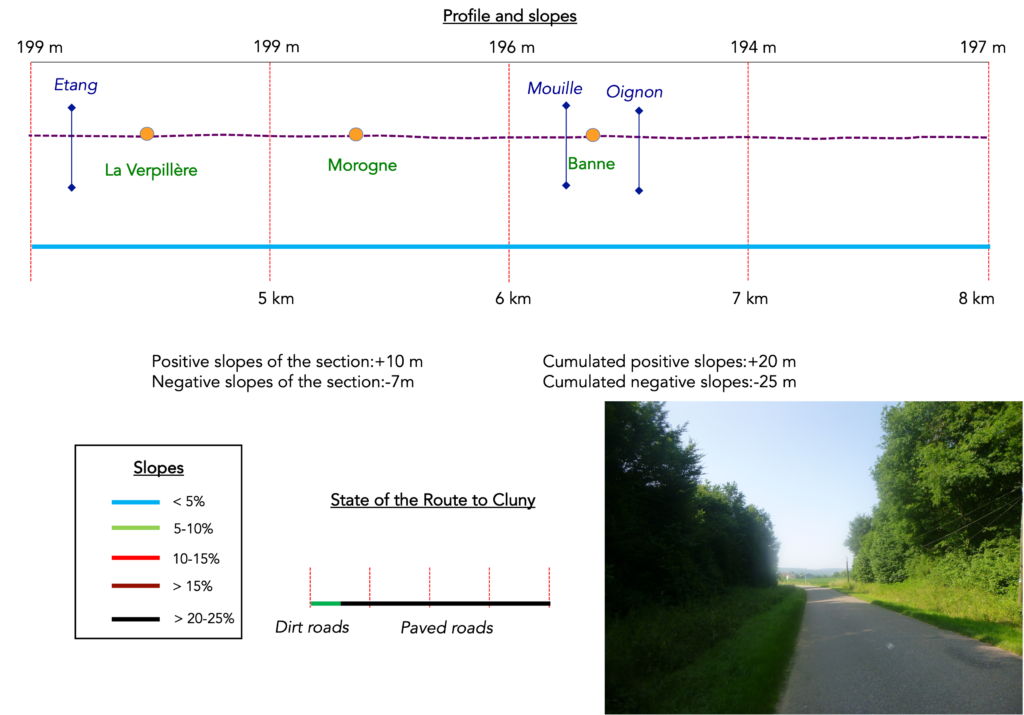

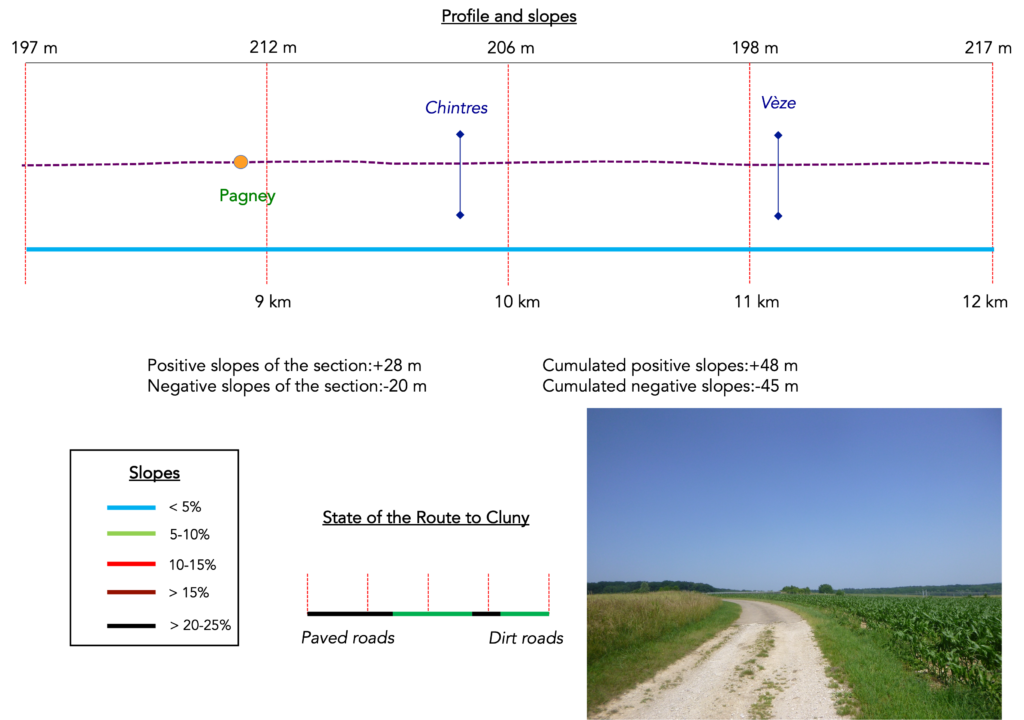

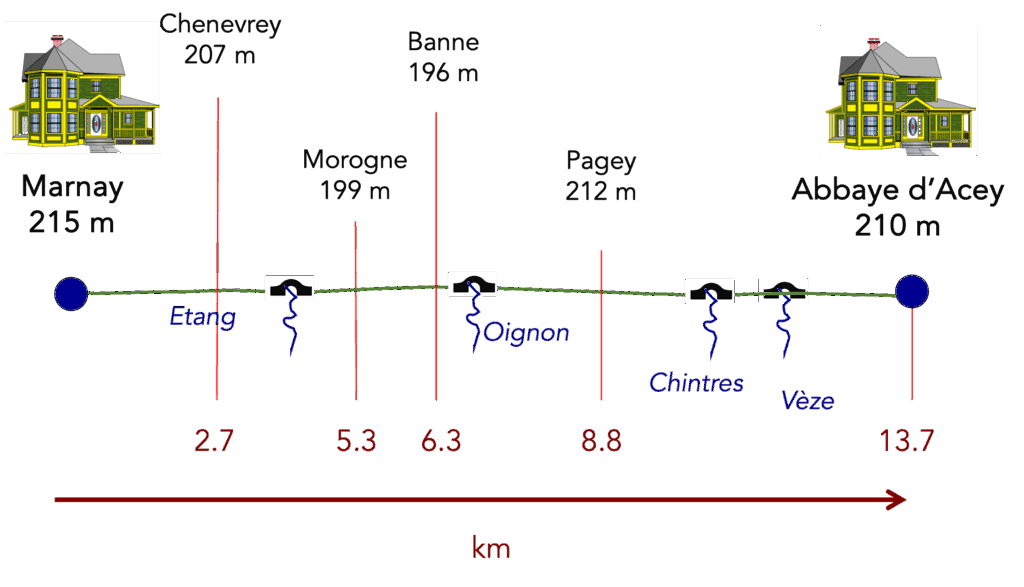

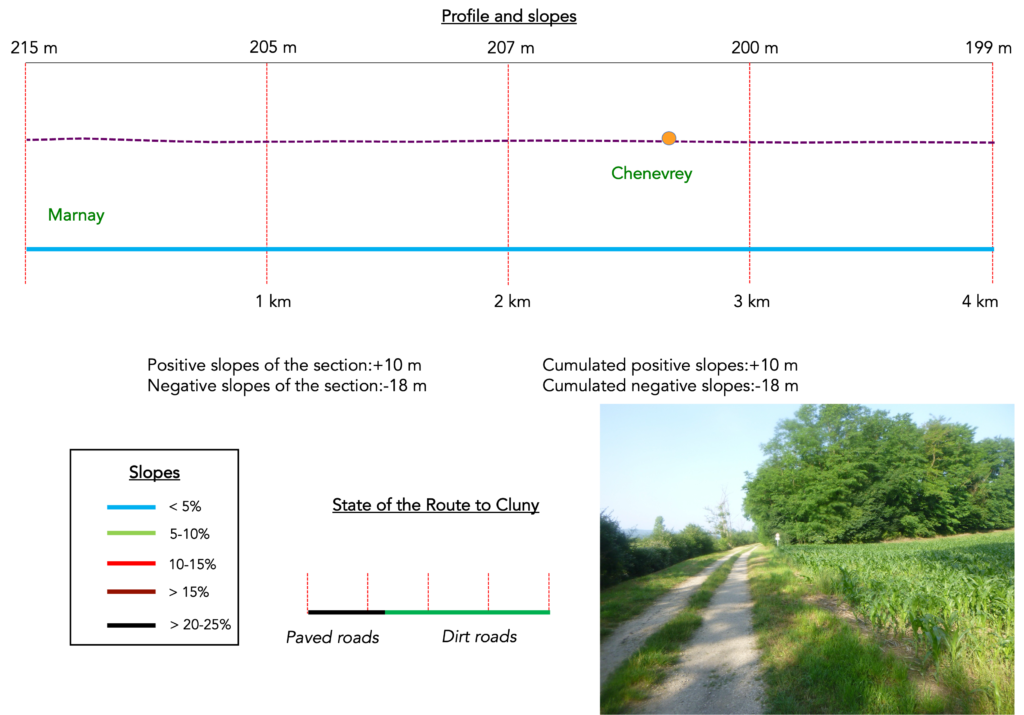

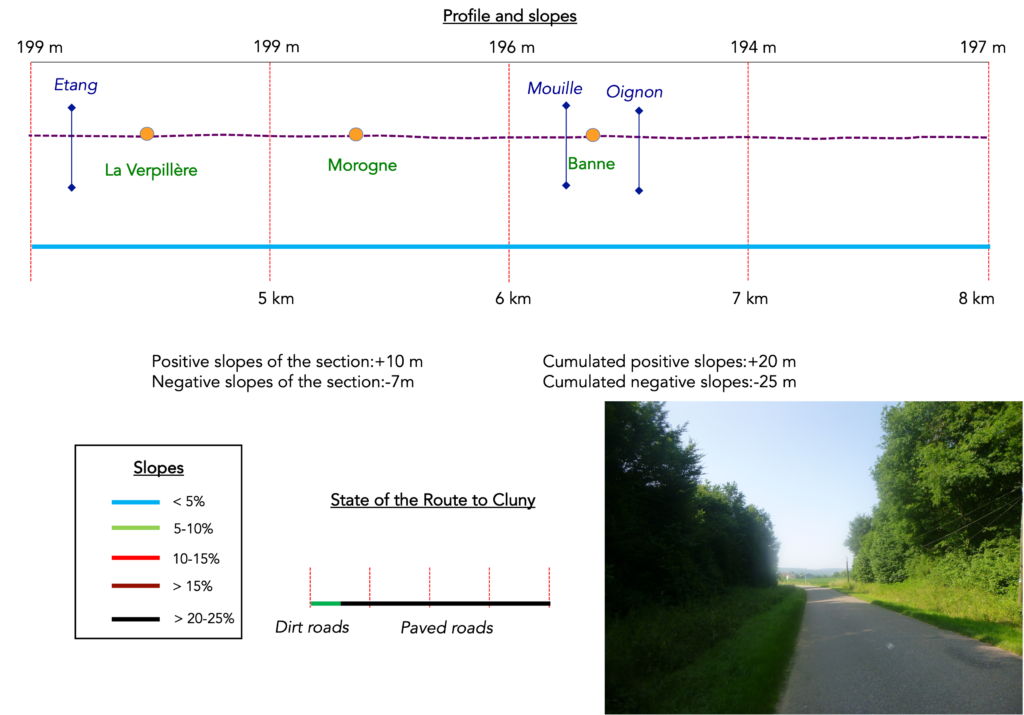

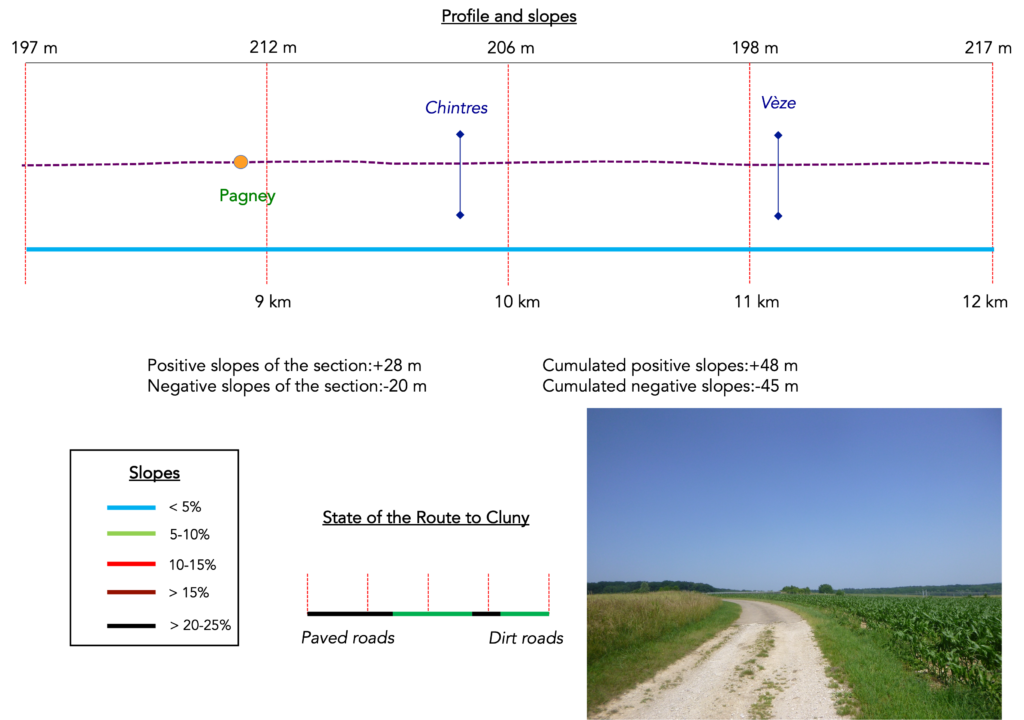

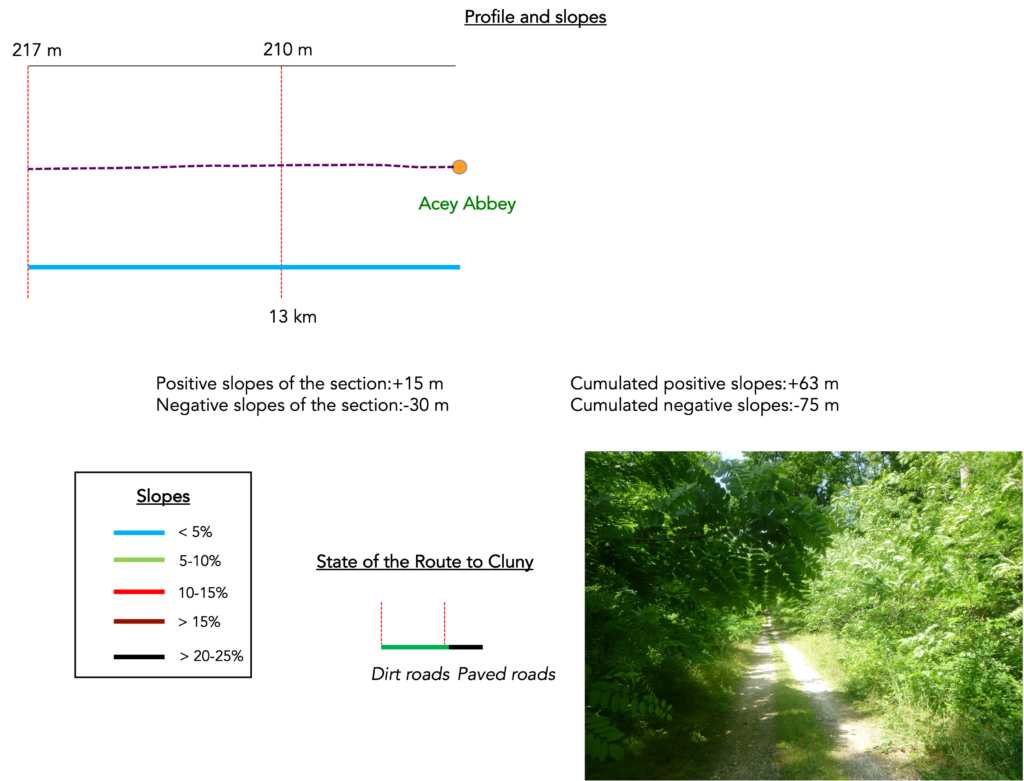

Difficulty level: The route of the day is gentle, with tiny elevation changes (+63 meters / −75 meters).

State of the route: Today, the sections on roads and on paths are balanced:

- Paved roads: 7.2 km

- Dirt roads: 6.6 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

Section 1: Along a long plain that stretches away

Overview of the route’s challenges: a route without any difficulty.

| Let us start from the central square where the shops of Marnay line up like a small stage of daily life. Time seems to flow at the pace of the inhabitants’ footsteps. Just a few steps away, the town hall, sober and dignified, watches over the square like a tutelary figure, witness of a town that combines its past with its present vitality. |

|

|

| In this compact center, almost folded in on itself like a shell, stands the church of Saint Symphorien. Its construction stretched from the eleventh to the fourteenth century, giving the building a composite yet deeply harmonious appearance. The stones, worn by the centuries, tell of an ancient faith rooted in the heart of the land. Listed as a Historic Monument, the church deserves to be explored for its Gothic volumes, its sculpted capitals and the traces of medieval art that have crossed the ages. Yet the pilgrim must first find the door open and have the privilege of admiring its sculpted masterpieces, so many silent messengers of history. |

|

|

Nearby, the Road to Santiago finds again its signs, its universal language of shells and arrows. However, the pilgrim encounters an old confusion. The shell, reassuring and beautiful emblem, does not indicate direction. It decorates but does not guide. Only the arrow, discreet and sometimes mistreated, shows the true route. Always remember this essential detail so as not to lose yourself in the twists of roads and countryside.

| The route then takes the short Rue Pourny, an unassuming lane, before turning right onto Avenue du Champ de Foire. |

|

|

| At the top of the road, near the post office, the route turns left and enters Avenue de Marnay-la-Ville. |

|

|

| The road then leads toward a large shopping center. Here, a surprise for the pilgrim accustomed to confusing waymarking appears, because for once the shell is correctly oriented. The symbol, faithful to its role, seems to smile at the traveler and say, “Go on, you are on the right way.” A rare moment of agreement between sign and direction. |

|

|

| But this harmony is short-lived. A few steps farther on, at the exit of the shopping center, everything becomes confusing again. The shell invites a left turn toward heavy traffic, like a misleading temptation. So you take out your guide, that indispensable travelling companion, and you check. In reality, you must continue straight ahead. Relief returns. On this route in Franche-Comté, you must constantly juggle between the signs placed on the ground and the instructions in the book, unless you carry a GPS loaded with local maps. |

|

|

| Strangely, just behind the crossroads, the shell reappears, this time perfectly oriented. Faithful once again, it greets the pilgrim. The route, now unambiguous, continues straight ahead, as if it had first wanted to test the attention of the walker. |

|

|

| The road then leaves the last houses of Marnay. Little by little, the walls grow farther apart, the roofs fade away, and the countryside opens wide and silent. |

|

|

| On the left, a path offers itself to the walker, like an invitation to leave the town and return to the horizon. |

|

|

| It is a wide stony path, firm beneath the feet, which sets off flat across open countryside. The sky takes all the space and the pilgrim finds again the breath of wide-open landscapes. |

|

|

| This path stretches between two hedges of broadleaf trees, a green corridor parallel to the road. The branches lean slightly, as if forming a vault, a ritual passage between the inhabited world and the open country. |

|

|

| Here, tall ash trees dominate the landscape. Their straight, slender trunks form a natural avenue almost ceremonial in appearance. Yet the attentive eye will also notice many oaks and maples, silent companions of the countryside, punctuating the landscape with their solid and familiar silhouettes that are characteristic of the region. |

|

|

| And the path continues for a long time in this way, without effort, as an invitation to let the mind wander. |

|

|

| The step becomes regular, almost meditative, carried by the simplicity of the earth road and the calm around. |

|

|

| Sometimes the trees in the hedges draw closer together, sometimes they allow more space. |

|

|

| Farther on, asphalt replaces the gravel for a while, a discreet sign that the village of Chenevrey is nearby. |

|

|

| A few discreet houses appear, nestled behind hedges or carefully tended gardens, silent witnesses of the peaceful lives of the inhabitants. |

|

|

When you reach the crossroads in the village, look carefully at the shell. In Franche-Comté, remember that the shell, often decorative, almost never indicates the exact direction. Only the arrow, discreet but reliable, must guide your steps. Here, it confirms that the route continues straight ahead and the pilgrim must trust this simple sign.

| A path then goes past a few scattered houses and farms on the edge of the village. |

|

|

| Then the wide path returns, parallel to the main road, as if to remind you of the continuity of the journey. The itinerary stretches on with the same gentle monotony, bordered with hedges and trees, silent witnesses of the passing of centuries. Here and there, wild walnut trees pierce the landscape, their knotted branches and serrated leaves bringing a touch of wildness to the general harmony. |

|

|

| The path runs parallel to the road where only a few vehicles pass, intensifying the feeling of solitude and isolation. The wide plain seems at times endless and time itself appears to stretch out along with the pilgrim’s steady steps. |

|

|

| From time to time, you can see cows in the meadows, peaceful and quiet. Although you are walking in a region renowned for cheese, especially Comté, the herds remain discreet, adding a touch of life without breaking the serenity of the countryside. |

|

|

| At the end of this long stretch, the hamlet of La Verpillière finally appears on the horizon, promising a pause and a transition in the walk. |

|

|

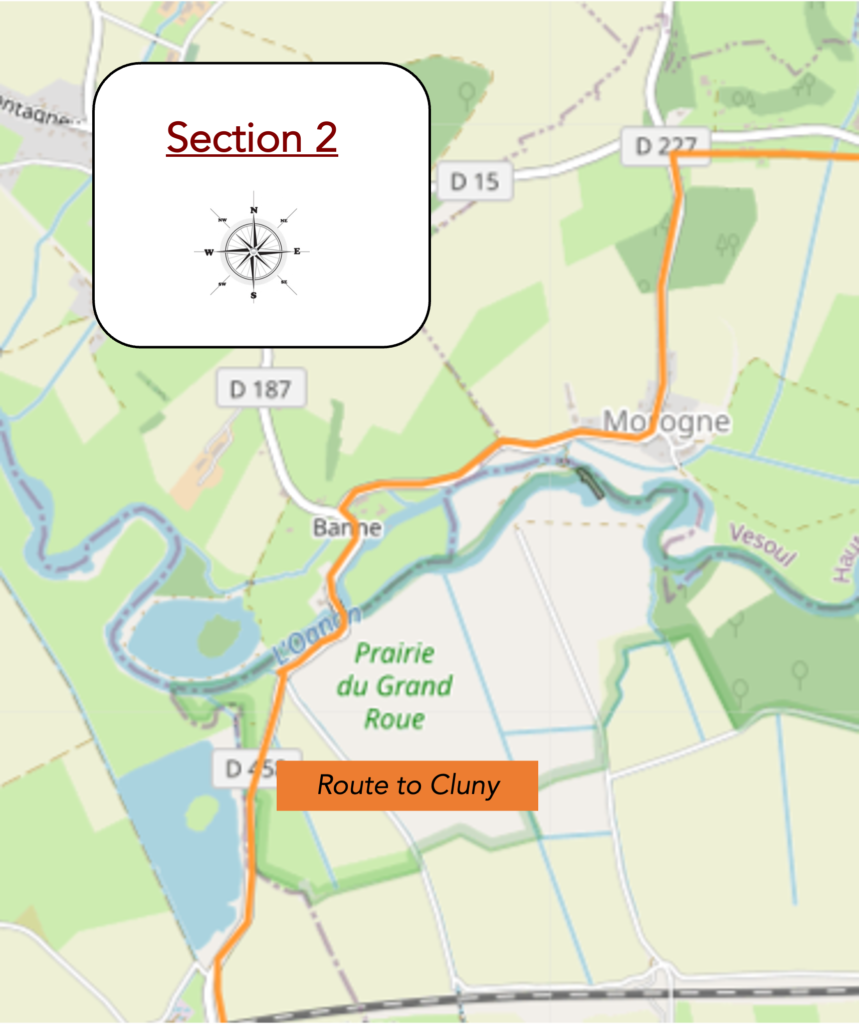

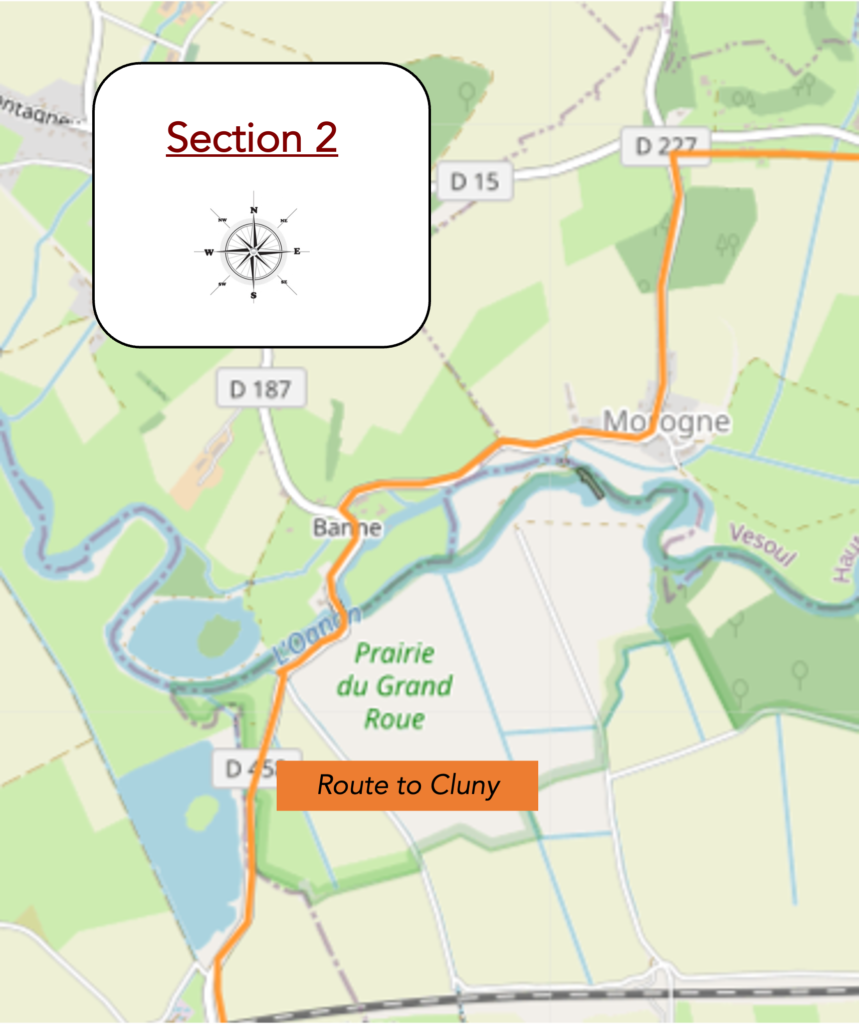

Section 2: Small hamlets in the plain

Overview of the route’s challenges: a route without any difficulty.

| The path then leaves the departmental road and continues toward the hamlet. |

|

|

| The path then draws nearer with a kind of languid movement toward the hamlet, like a release after the monotony of long straight lines. Each step seems lighter thanks to the nearness of the houses and to the feeling that discreet life begins again behind the hedges and gardens. The horizon tightens and one senses that the solitude of the fields is slowly being left behind. . |

|

|

| Here, the route returns to asphalt, a regular line that follows small villas neatly aligned, modest in architecture but carefully maintained, each with its little garden and trimmed hedges. The parallel road reminds you that the path always remains linked to modern life even when it wanders through the countryside. |

|

|

| At the end of this long straight stretch, charmingly named Chemin du Pommery, the route changes direction. The shell, faithful for once, confirms the movement of the arrow. You must turn left. The pilgrim follows this instruction docilely, relieved not to have to doubt, and settles again into his rhythm. |

|

|

| The road then curves gently, winding from one village to another through countryside tinged with small woodlands. Groves of varied species dot the space like islands of shade. The walk becomes more pleasant, livelier, almost musical. |

|

|

| Very soon, the road reaches Morogne. |

|

|

| In the village, it is the orderliness of the place that strikes the eye first. Everything here breathes quiet harmony. Stone dominates, pale and massive, imposing its presence. A string of large old houses lines the road, each marked by the noble wear of time. |

|

|

| The old washhouse, simple and graceful, evokes the timeless gestures of washerwomen bending over clear water and gives Morogne the soul of another age. |

|

|

| The road then leaves the village, passing large farms. These farms are neither picturesque nor decorative. They were built for use, for agricultural life, solid and functional above all. They stand as a concrete reminder of the labor of the land. |

|

|

| Sometimes cows appear in the meadows. They graze slowly under walnut and ash trees, indifferent to the pilgrims passing nearby. Here it is the Montbéliarde that reigns supreme, with its red and white coat and calm gaze. This breed, emblematic of the region, is the beating heart of the farming of the Franche-Comté, provider of rich milk and renowned cheeses. |

|

|

| In this countryside, pasture far outweighs crops. Livestock farming is the essential activity, while cultivated fields are fewer, scattered among the meadows, modest but necessary. The land is offered above all to the cattle, and this has shaped the economy and the landscape since long ago. |

|

|

| The road then continues along hedges of broadleaf trees in the countryside. |

|

|

| Farther on, the road reaches Banne, a small hamlet almost hidden in greenery. Its houses seem to emerge from the foliage, as if they had chosen to hide under the shelter of trees to preserve their tranquility. For the walker, this retreat into leaves feels like a gentle intimate pause, a quiet stop in the heart of the woods. |

|

|

| In Banne, the road bends sharply, turning at right angles, as if hesitating for a moment over which direction to take. The village, folded back on itself, stays behind, while the route opens again toward the countryside. |

|

|

| Very soon, the road crosses a tiny trickle of water, the stream of La Mouille. It is little more than a whisper among the mosses, a discreet trace gliding through the grass. Yet it carries the humility of the small sources that patiently feed the life of plains. |

|

|

| The road then skirts the hamlet, disappearing gently behind hedges of broadleaf trees, like a moving frame of leaves accompanying the pilgrim’s steps as a benevolent presence. A little farther away, a metal bridge appears, painted deep green, a sturdy iron structure of the kind Gustave Eiffel imagined so often in the nineteenth century. |

|

|

| It is along this bridge that one crosses the Ognon, a broad and ample river, yet peaceful, carrying its current with sovereign discretion. It flows silently, as if it had chosen restraint rather than force. |

|

|

| On the other side of the bridge, the road unfolds in light curves, winding under ash trees with long branches that cast dancing shadows. It is precisely here that one leaves Haute-Saône for a moment to enter the department of Jura, a symbolic passage between two neighboring worlds with subtle differences. |

|

|

| Then a very different landscape opens. It is a silent passage, almost bare, but with striking peace. The countryside spreads into a wide uncovered plain, without trees or hills, like an immense sheet laid across the earth. The eye loses itself in this expanse of grass and the road, straight as if cut with a knife, splits the horizon without obstruction. |

|

|

| A little farther on, a hedge of broadleaf trees reappears, breaking the monotony. At the warmest hours, it offers a providential shelter, a saving shade where one gladly steps aside to rest a moment. |

|

|

| Finally, on the horizon, a slight rise appears, an almost imperceptible but steady climb bordered by fields of corn whose stalks rustle in the wind. It leads to the bridge that crosses the railway line, a modern threshold laid across an ancient rural landscape. |

|

|

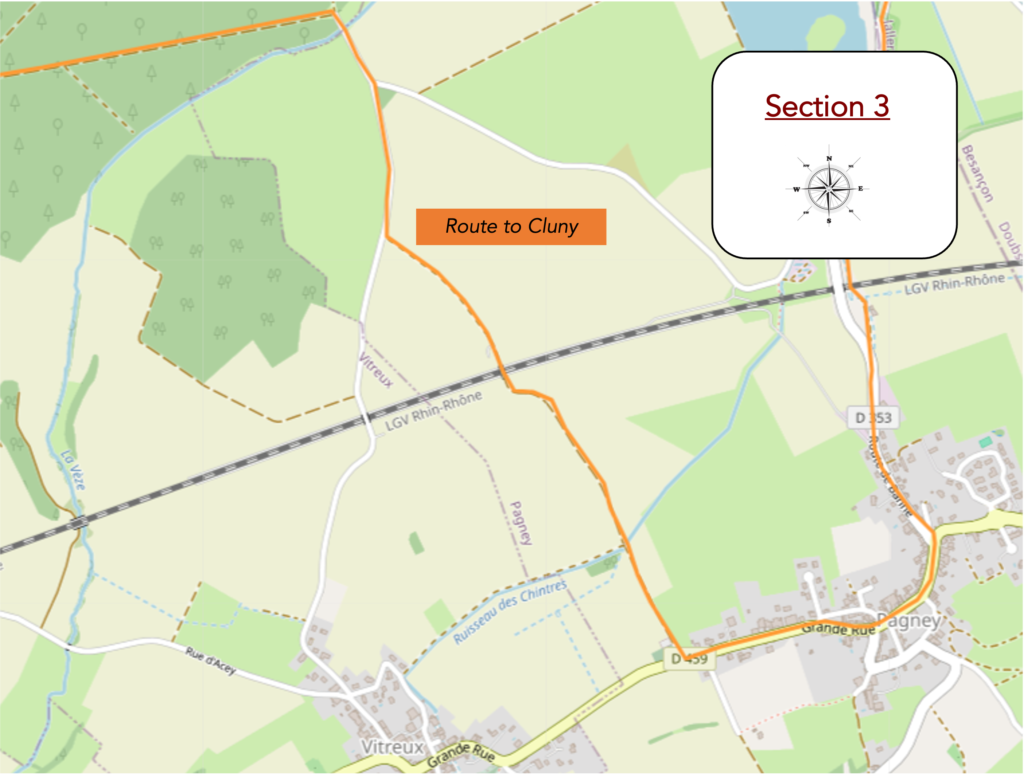

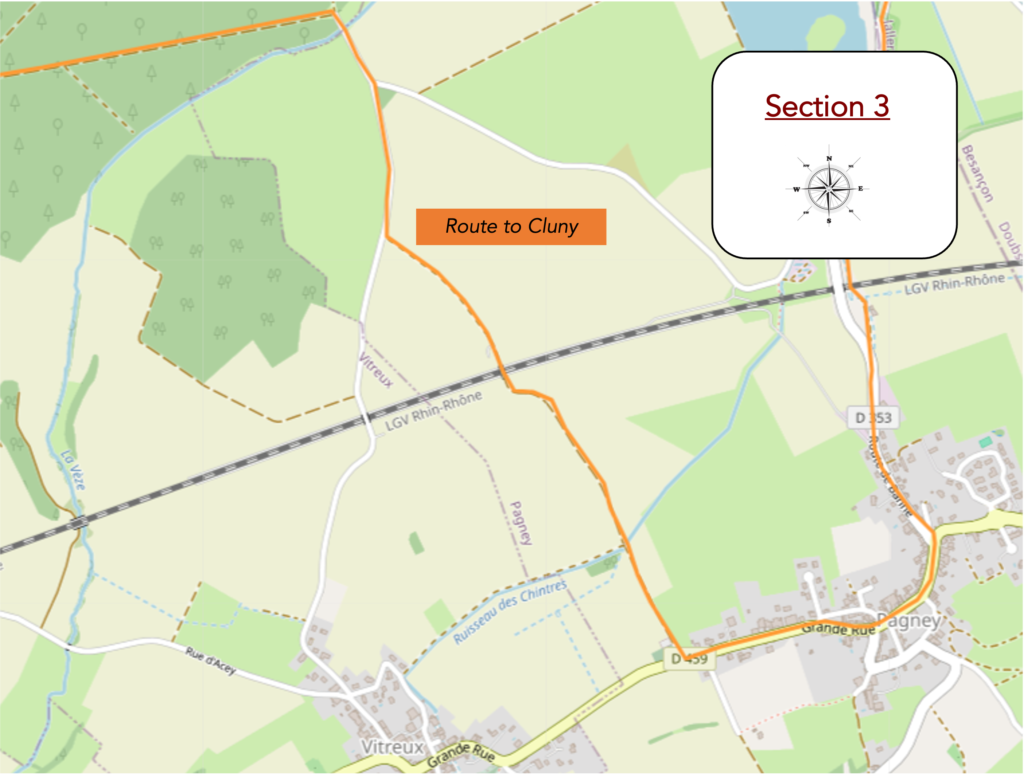

Section 3: A little game with the high-speed train

Overview of the route’s challenges: a route with no difficulty.

| The road first slopes up slowly, then climbs more decisively up the ramp that leads over the high-speed railway line. Here the TGV races past at full speed, a metallic flash impossible to catch, flying along at 320 km per hour. It is the Rhine-Rhône line, inaugurated in 2011, which links Dijon to Mulhouse while crossing the heart of the Franche-Comté. The contrast is striking. On one side, the measured pace of the pilgrim, on the other, the dazzling speed of modernity. Between Besançon and Dole the connection is now almost immediate. Yet for the surrounding villages this technological feat remains almost invisible, nothing more than the silent passage of a train too fast for them. The road remains the only link, fragile and necessary, with a wider world. |

|

|

|

|

| A gentle descent then begins, the road inclining toward Pagnay. Soon the first houses appear, scattered over a wide space because the village stretches endlessly. Here the high-speed train passes only a short distance away, yet paradoxically no train stops. A bus nevertheless runs through this countryside, a rarity that almost feels miraculous in rural France so often abandoned by public transport. |

|

|

| The heart of the village reveals itself, simple and modest. In the center, the town hall stands next to a mission cross that speaks of an old piety. No shop animates the streets, only silence keeps watch over the place. |

|

|

| Then the road crosses Pagnay. It passes in front of the church of St Léger, dedicated to the bishop of Autun, a martyr of the seventh century. The building, of sober and severe Cistercian style, was built between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, succeeding an older church. In the seventeenth century its nave was altered, giving the whole structure a unique appearance halfway between medieval austerity and later Baroque reworking. |

|

|

| Leaving the center, the road skirts the château of Beauregard, hidden behind its gates and its trees, a vast private residence within a park where one can still sense the fragrance of another age. |

|

|

| The village fades gently. The road passes the last houses like a slow withdrawal from inhabited life toward open countryside. |

|

|

| At the corner of the cemetery the route suddenly breaks away from the main axis. It turns at a right angle, leaving the main road to enter a secondary road, as if the pilgrimage were suddenly returning to its more intimate rhythm, far from the passage of cars. |

|

|

| Very soon the asphalt disappears beneath your feet. Beaten earth, compact and strewn with stones, takes over. |

|

|

| The path heads straight ahead, entering the bare plain where meadows and cornfields stretch endlessly. The landscape, wide and silent, opens like a blank page that the pilgrim crosses, with only the rhythm of footsteps marking the passage of time. |

|

|

| The path, stubborn and unwavering, runs for a long time through this monotonous plain. Its implacable line leads again toward the railway, as if drawn by this modern scar that cuts across the countryside. |

|

|

| It then crosses the high-speed railway. If chance offers you the spectacle of a train at full speed, prepare yourself. It is like thunder passing, a rush of air and noise that sweeps everything away but vanishes within seconds, leaving behind an almost unreal silence, as if nothing had happened. |

|

|

| Soon the rigidity of the path softens. The beaten earth gives way to a gentler ground, a mixture of soil and grass. Your foot sinks slightly and the step finds a more natural comfort again. |

|

|

| The shell is still there to reassure you, even if it still lacks the correct direction. |

|

|

| Always straight ahead, the path continues through the bare plain under the wide sky, between meadows and corn. The horizon seems unchanging, yet little by little a fringe of trees appears, a promise of shade and coolness. The wood is getting closer. . |

|

|

| Suddenly the path turns sharply at a right angle. The grass disappears, replaced by a covering of stones. A hedge of shrubs runs alongside it like a discreet guardrail until it reaches a small asphalt road. |

|

|

| The road, timid at first, gradually draws nearer to the wood. The canopy closes overhead, suggesting a more secret atmosphere. Here, far from the villages, no farmhouse interrupts the space, only the presence of tractors in the distance, laboring silhouettes tracing furrows across the fields. |

|

|

| Another right-angle bend leads you into a more intimate landscape. The tiny stream of the Vèze hides in tall grass, almost invisible. From time to time a thin herd comes to seek refuge in the shade of tall broadleaf trees, as if wanting to escape the unrelenting sun. |

|

|

Straight ahead, it leads to a barrier like a symbolic gate to be crossed.

| A long, straight crossing under the trees then begins. The step becomes regular, easy and almost mechanical. Nothing obstructs the walk; the path unwinds like a continuous thread within the green half-light. |

|

|

| Ash trees largely dominate this forest. Their slender silhouettes form a light ceiling where a few maples, young oaks, beeches and more discreet hornbeams mingle. Here and there, ferns spread across the ground like large carpets, undeniable sign that the wood keeps a persistent humidity, like a sponge of greenery. |

|

|

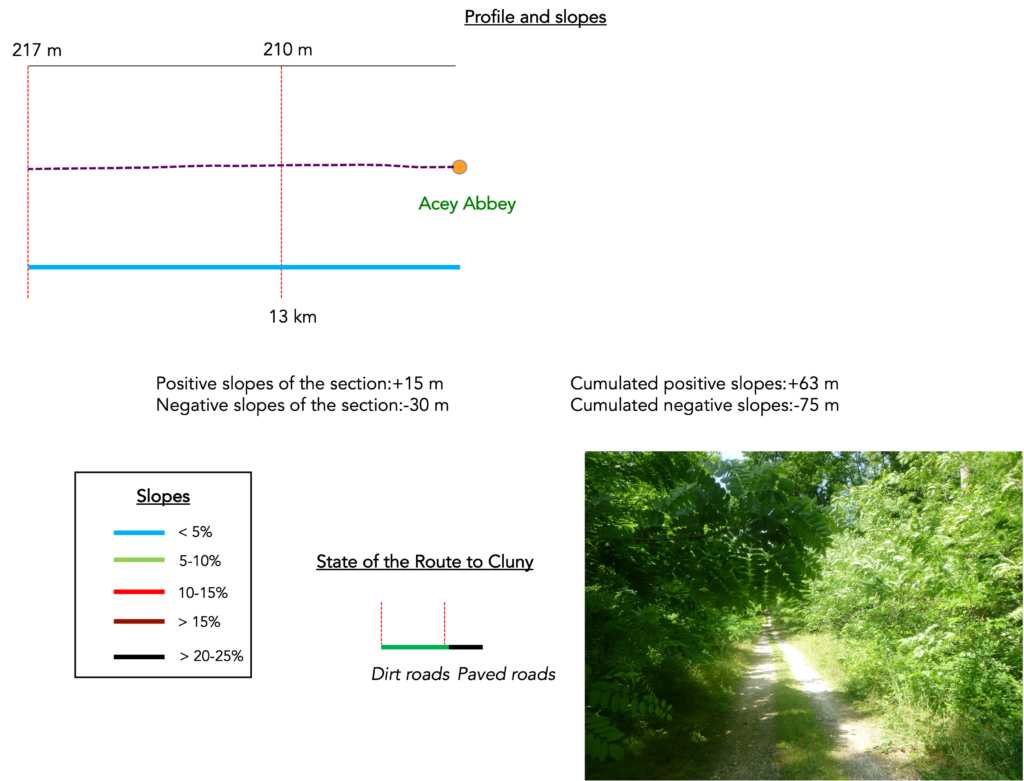

Section 4: On the way to a beautiful abbey

Overview of the route’s challenges: a route with no difficulty.

| The path still wanders a little, always flat and straight ahead, beneath the generous canopy of trees. The air is fresher, softened by the shade, and each step feels lighter. |

|

|

| Then suddenly it opens onto a clearing, a wide breath of light after the thickness of the wood. A barrier also marks the exit from the forest. . |

|

|

| There, in the distance, you finally glimpse what you have been waiting for, the bell tower of the abbey church rising up, plain and massive, on the other side of a wood. It appears discreetly, yet full of promise. |

|

|

| At the end of the clearing, the wide earthy path returns under the cover of the trees. |

|

|

| The pilgrim then walks once again into a peaceful undergrowth. |

|

|

| Here, beeches and hornbeams, sometimes stunted by the poor soil, compose the landscape. Their density creates a more secret atmosphere that feels almost enclosed. |

|

|

| Soon the path reaches a paved road. It turns at a right angle and leads directly toward the abbey. |

|

|

| Little by little, around the bend, the stone buildings appear. Massive but restrained, they announce the spiritual presence of the place. |

|

|

The Abbey of Notre-Dame d’Acey, founded in 1136, finally comes into view, peaceful and authentic. It is the only Cistercian abbey still inhabited by a monastic community in the entire region.

| A magnificent park, calm and full of charm, stretches nearby. Just below, almost hidden behind the trees, stands an industrial building. For more than seventy years the abbey has partly lived thanks to this discreet economic activity, a metal surface treatment plant that employs a few monks and lay workers. It is a surprising alliance between monastic silence and modern industry. |

|

|

|

|

| In the Middle Ages the abbey experienced its golden age, to the point of founding a daughter abbey in Hungary. History was later harsh with it. It suffered destruction during the Ten Years’ War from 1636 to 1644, then a fire in 1683. During the French Revolution it was sold as national property in 1791 and passed through different hands before regaining its vocation in 1873 with the return of Cistercian monks. Its architecture reflects the Cistercian spirit, sobriety, pure lines and functionality. The style combines Romanesque and Gothic elements, enriched today with luminous contemporary stained glass. Today the abbey is still home to a community of Cistercian Trappist monks. They follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, their days structured between prayer and work, with seven daily offices from dawn until nightfall. |

|

|

| The abbey also offers guest lodging, open to pilgrims and to all who seek spiritual retreat. Guests are welcomed in a simple setting and invited to share the silence of the place and, if they wish, to take part in the offices. |

|

|

LogOfficial accommodations in Burgundy/Franche-Comté

- Gîte du Moulin, Banne; 03 84 32 26 85; Gîte

- Abbaye d’Acey ; 03 84 81 04 11; Gîte

Jacquaire accommodations (see introduction)

Airbnb

- Chenevrey et Morogne (4)

- Banne (1)

Each year, the route changes. Some accommodations disappear; others appear. It is therefore impossible to produce a definitive list. This list includes only places to stay that are located directly on the route or within one kilometer of it. For more detailed information, the guide Chemins de Compostelle en Rhône-Alpes, published by the Association des Amis de Compostelle, remains the main reference. It also contains useful addresses of the bars, restaurants, and bakeries along the route. On this stage, if there is no space at the abbey, which is rare, you will have to continue farther along the route. It must be said that this region is not a tourist area. It offers other kinds of riches, but not an abundance of infrastructure. Today, Airbnb has become a new point of reference for travelers, and we cannot ignore it. It has become the most important source of accommodation in every region, even in those that are not particularly tourist-oriented. As you know, exact addresses are not directly available. On this stage, accommodation is very limited. If there is no space at the abbey, you will have to continue to the gîte at Banne, beside the road. It is always strongly recommended to book in advance. Finding a bed at the last minute is sometimes a stroke of luck; it is better not to rely on that every day. When you make reservations, ask about the possibility of evening meals or breakfast.

Feel free to leave comments. That is often how one climbs the Google rankings, and how more pilgrims will gain access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 11: From Acey Abbey to Mont Roland |

|

|

Back to menu |