Through the Chambaran woods before discovering another medieval gem

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

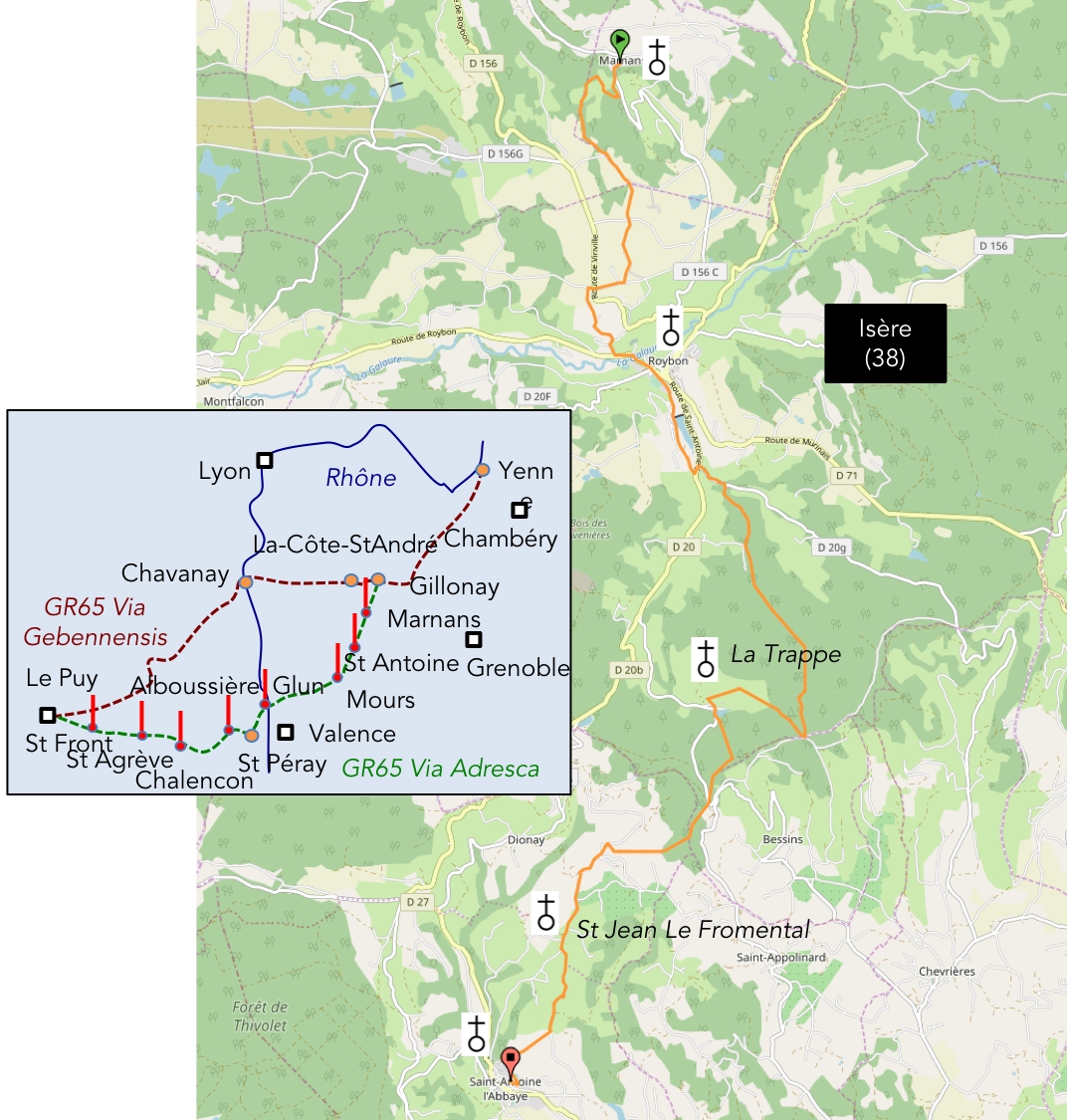

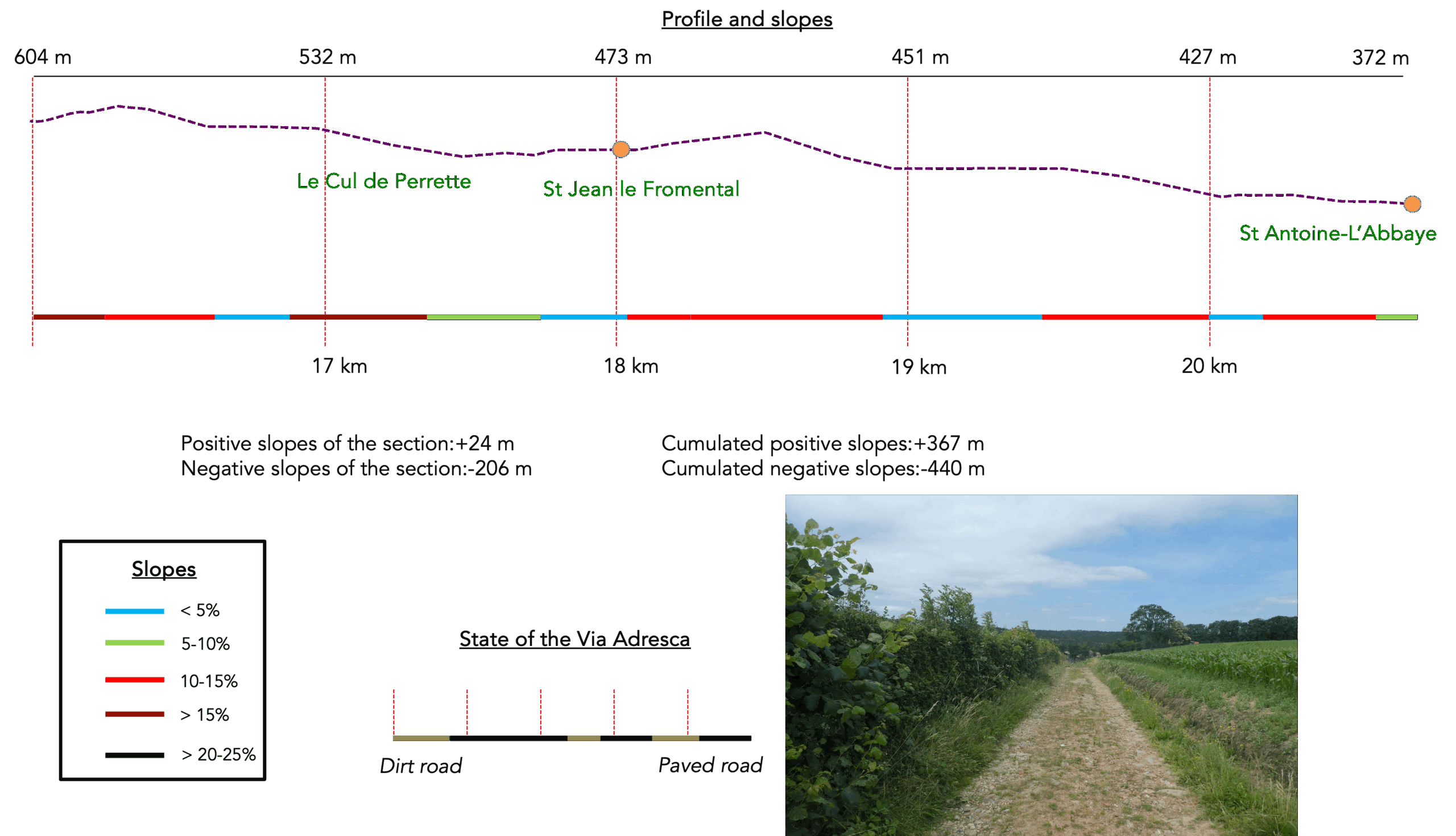

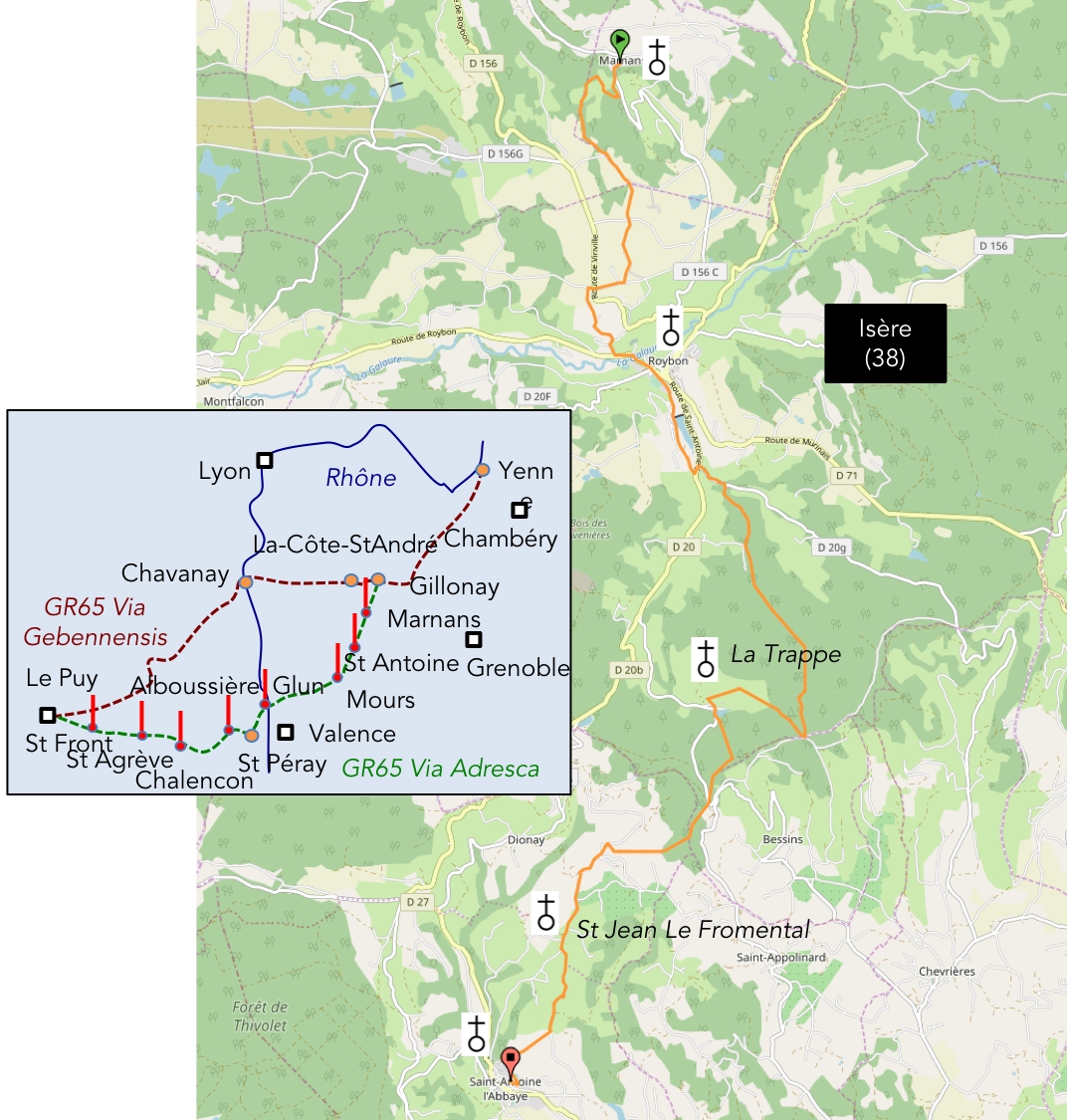

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/marnans-auvergne-rhone-alpes-france-32806286

| Not every pilgrim feels comfortable using GPS devices or navigating on a phone, especially since many sections still lack reliable internet. To make your journey easier, a book dedicated to the Via Gebennensis through Haute-Loire is available on Amazon. More than just a practical guide, it leads you step by step, kilometre after kilometre, giving you everything you need for smooth planning with no unpleasant surprises. Beyond its useful tips, it also conveys the route’s enchanting atmosphere, capturing the landscape’s beauty, the majesty of the trees and the spiritual essence of the trek. Only the pictures are missing; everything else is there to transport you.

We’ve also published a second book that, with slightly fewer details but all the essential information, outlines two possible routes from Geneva to Le Puy-en-Velay. You can choose either the Via Gebennensis, which crosses Haute-Loire, or the Gillonnay variant (Via Adresca), which branches off at La Côte-Saint-André to follow a route through Ardèche. The choice of the route is yours. |

|

|

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Today’s stage presents itself as an adventure as fascinating as it is revealing. It is not merely a crossing of peaceful landscapes and majestic forests, but a true initiatory journey, immersed in the religious and spiritual currents that marked the Middle Ages. The route leads you from discovery to discovery, both geographical and historical, and takes you into a world forgotten by many. For, may we dare admit, how many among us had heard of St Antoine-l’Abbaye before this journey? Very few, no doubt. And yet, this place, so discreet and so unique, surely deserves a prominent place in the collective imagination. Why, indeed, does Isère not make more of an effort to showcase the hidden treasures of this land? Here, we will pay tribute to those who shaped the spirituality of this region: the Benedictines, the Antonins, and even the Trappists, whose remains still permeate the stones of these places. A dense program, a stage rich in history and sacred silence.

The Lower Dauphiné, this region that precedes the arrival of the Alps, is a land of contrasts where the soft rock of molasse mixes with the memories of ancient glaciations. The forests, stretching as far as the eye can see, the pure and almost solemn air, seem destined to keep their secrets. Far from being a land simply sculpted by glaciers, here the soil is an accumulation of sediments deposited over time by the glacial waters descending from the Alpine massifs. These deposits from the Quaternary era, often hidden beneath dense vegetation, cover the valleys like a cloak of history frozen in the ground. The soil itself is a compromise between wealth and poverty. Sometimes nourished by fertile silt, sometimes barren, drowned in sand that struggles to retain the benefits of moisture. The humus, victim of the weather, seems to constantly escape from the land. The forests that cover the region, long and multiple, often reflect a capricious soil. The geography, for its part, remains simple but rugged, like this land which, with every step, seems to reveal a little more of its intimate history.

|

|

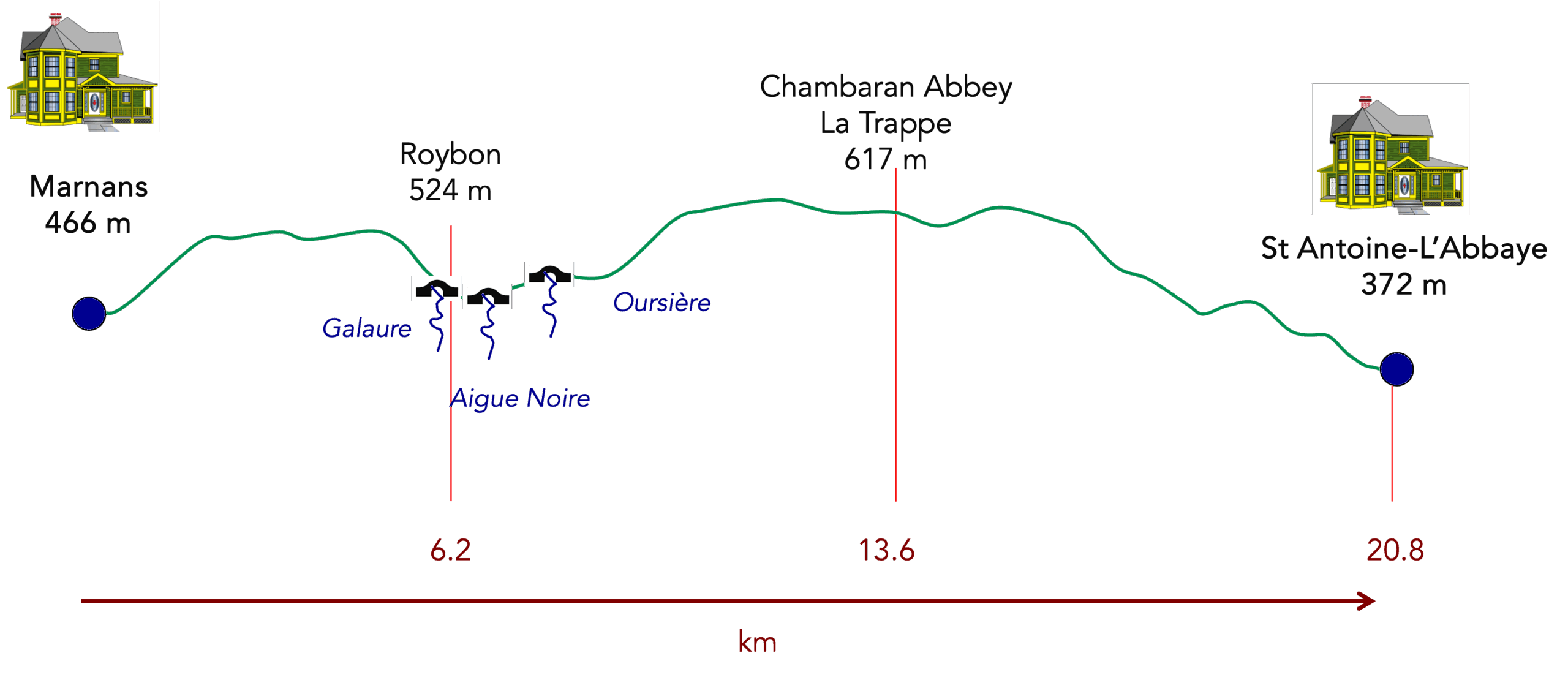

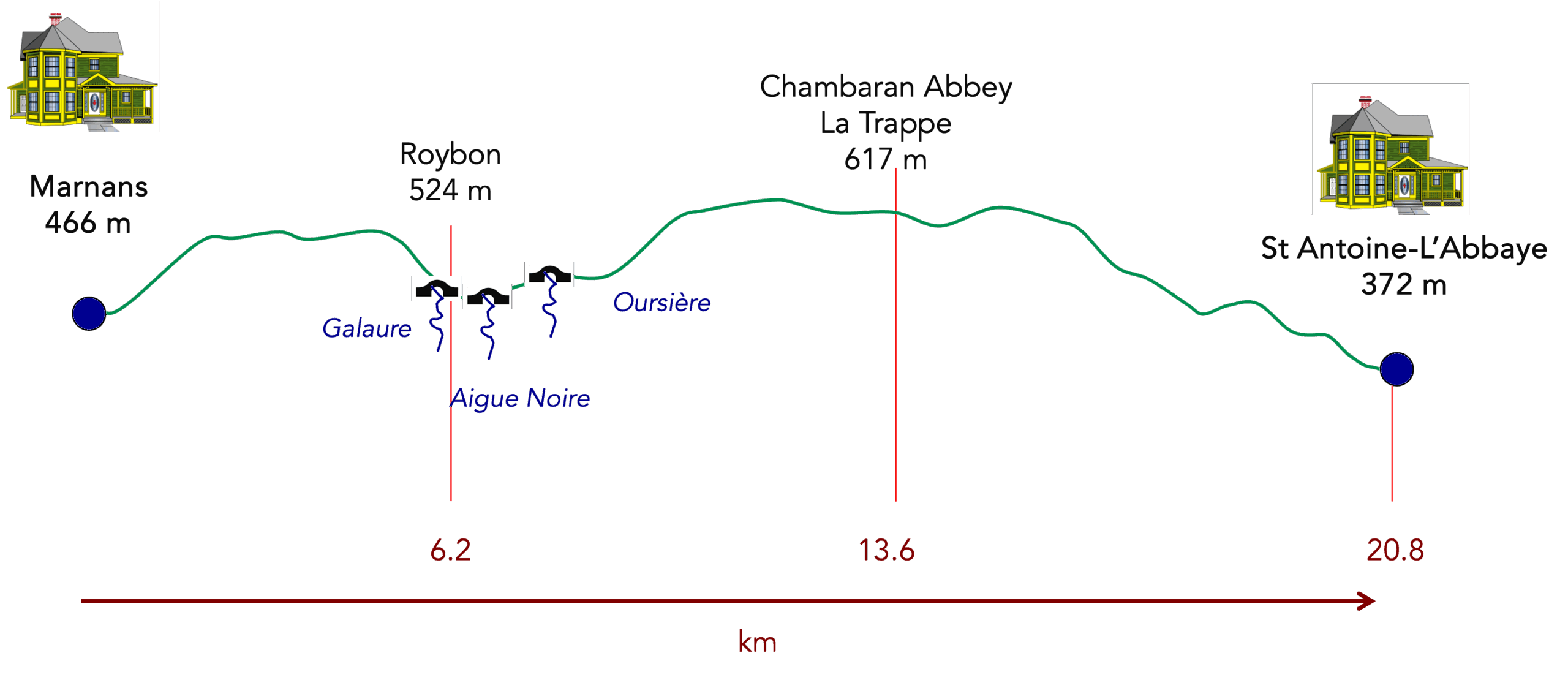

You start from Marnans, a small village located at the foot of the Bièvre, and climb the slopes to the high plateaus of Chambaran. There, the forests spread with a discreet majesty, their shadows inviting contemplation, their skies open to an uncertain future. Then, after penetrating these wooded areas, you begin a descent toward the Isère valley, a return to light, to the bottom of the valleys where the river, like a metallic serpent, winds between the mountains.

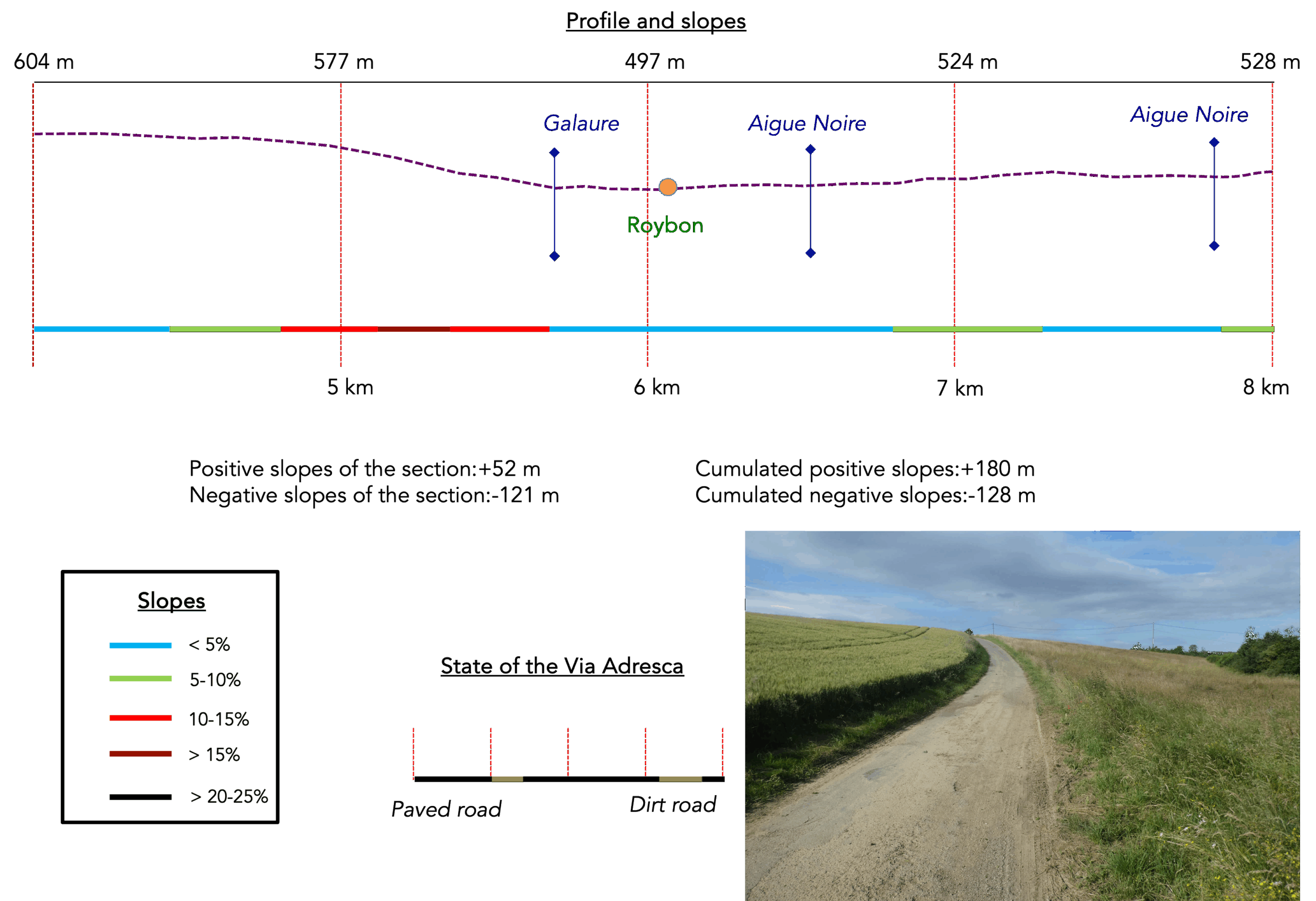

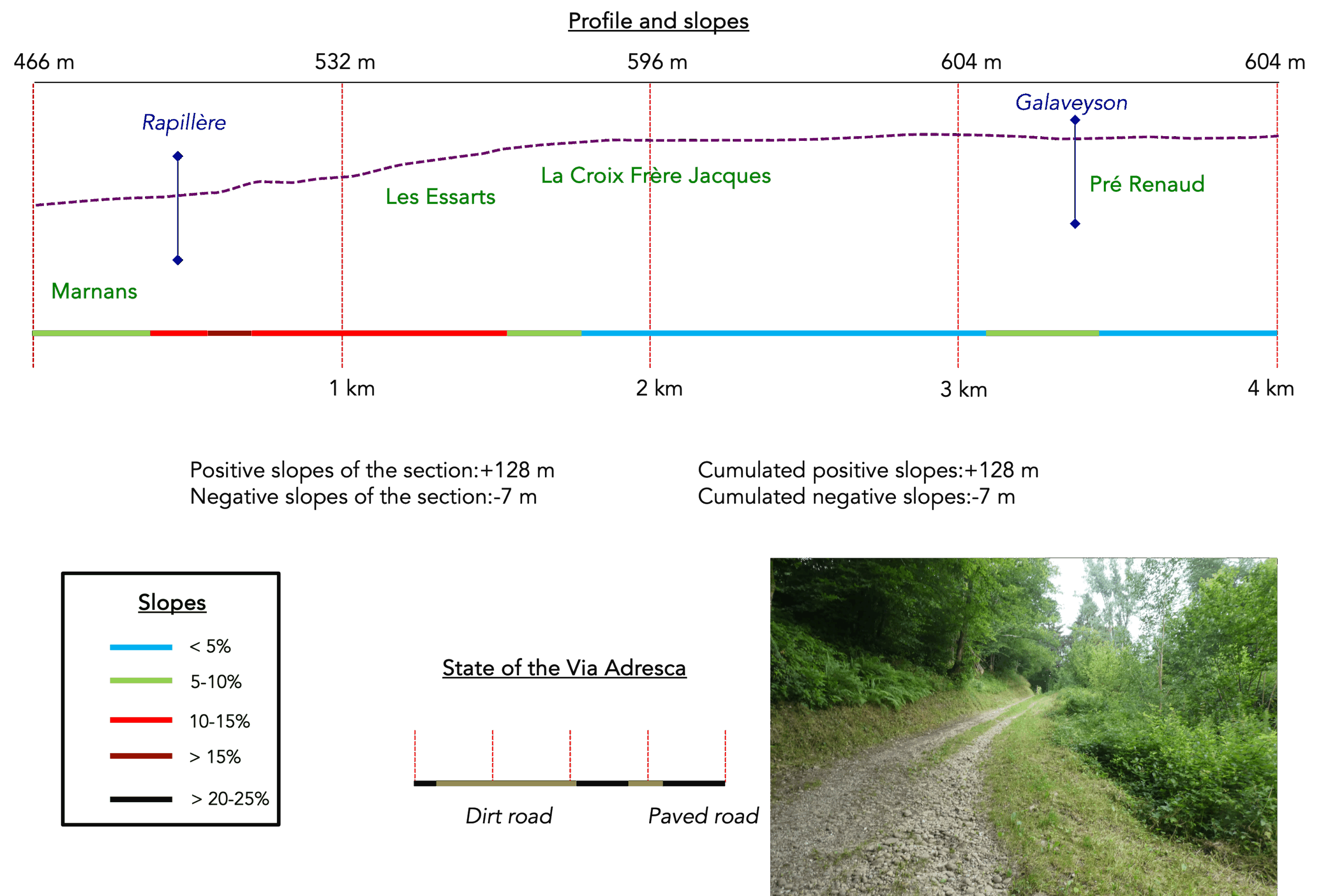

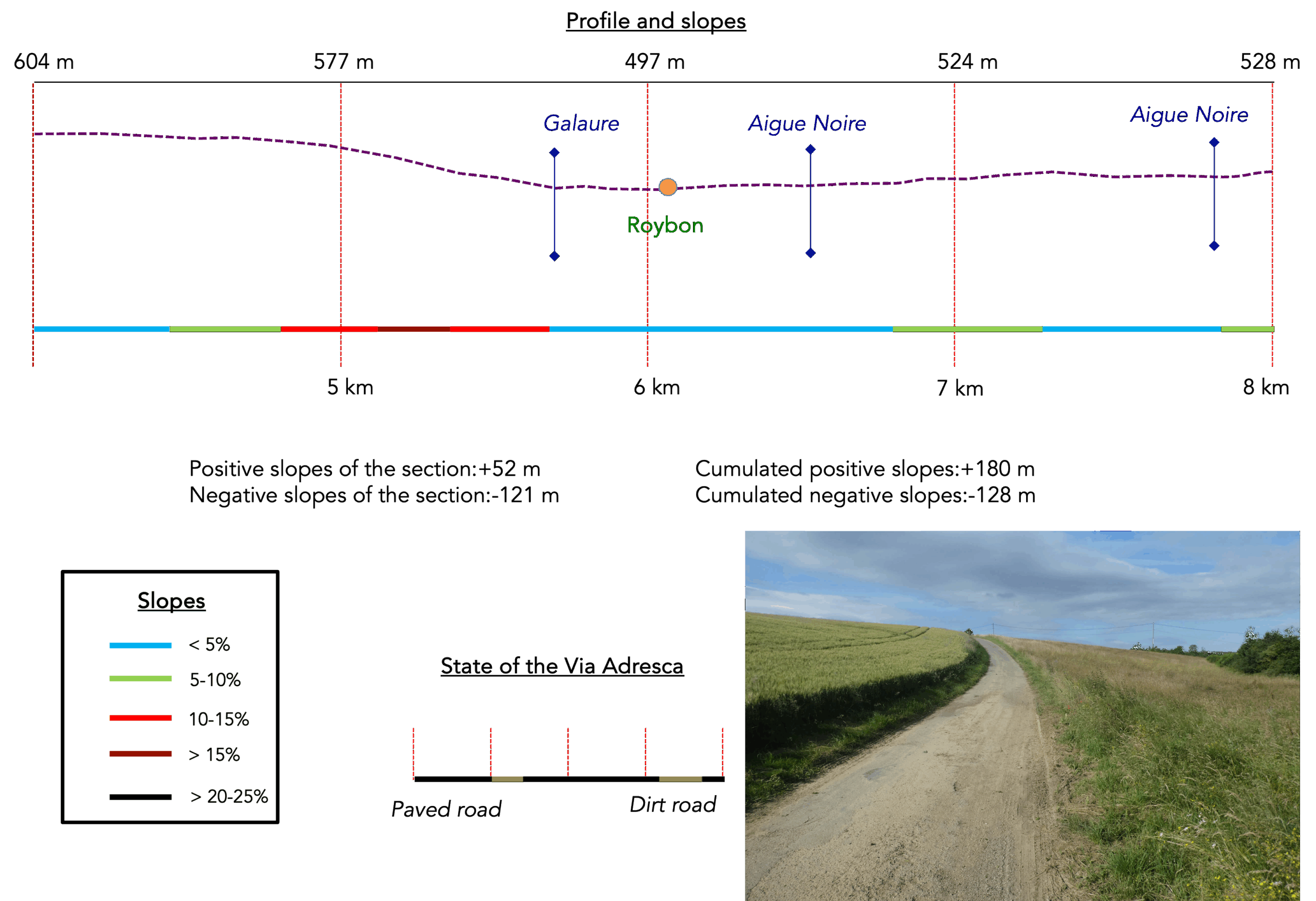

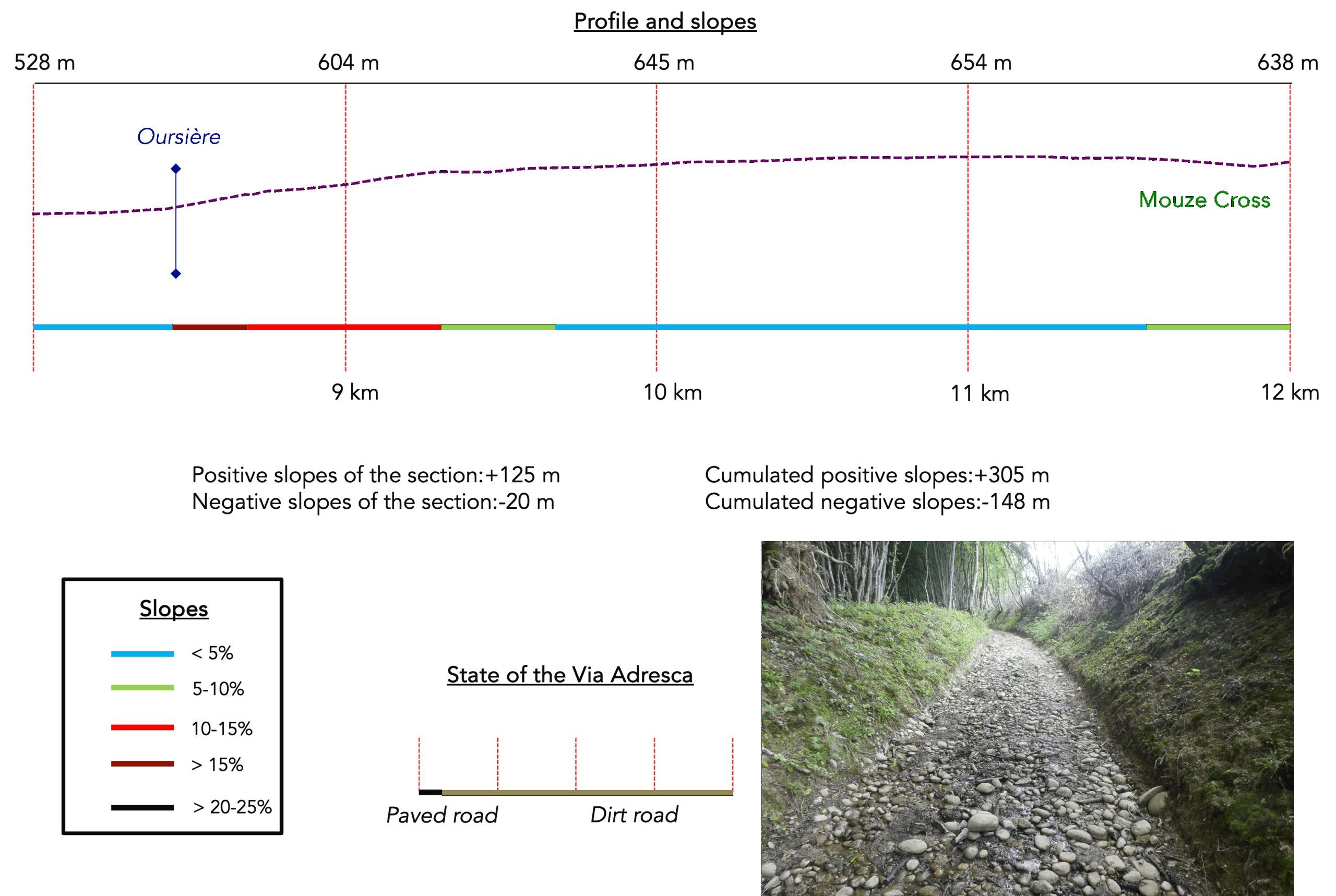

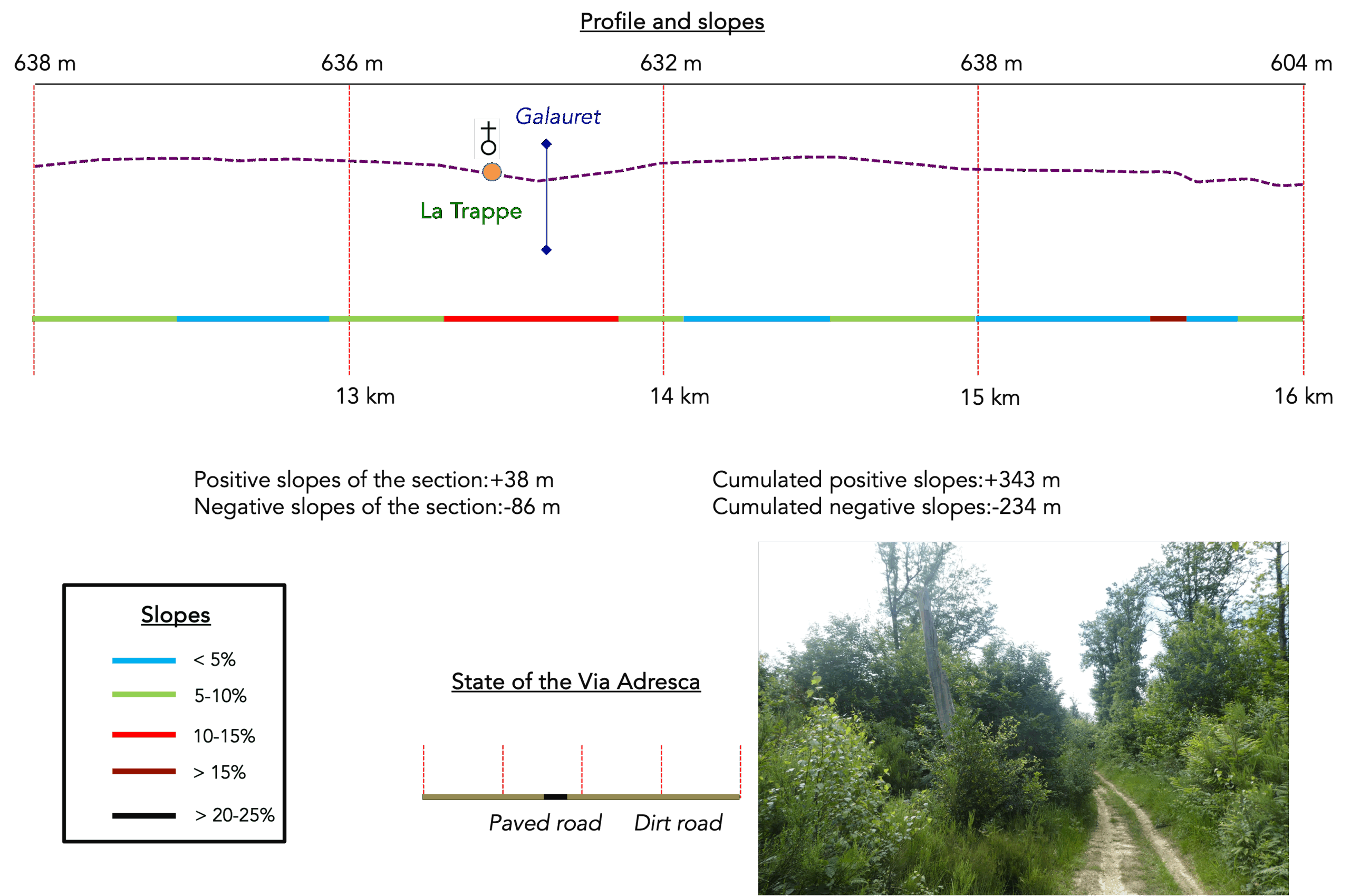

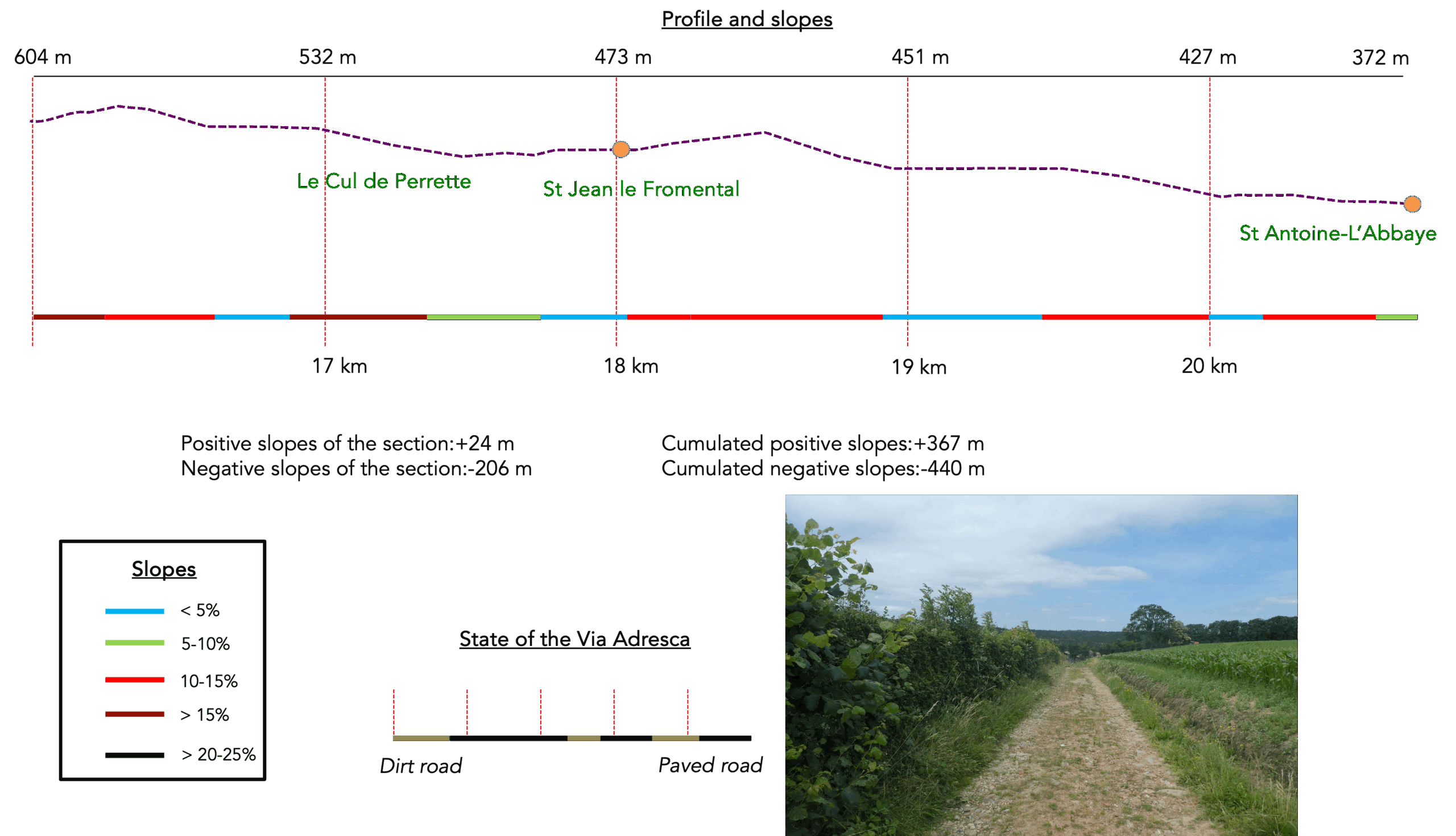

Difficulty level: The route for today is relatively modest, at least in terms of elevation changes (+357 meters/ -440 meters). it is a medium-level stage, within the reach of everyone. However, the challenge lies in some steeper sections, especially at the beginning of the day, where slopes nearing 15% will test the legs of the most determined. These slopes also appear in the Gargamelle forest, a place both magical and feared, where the climb seems never-ending. As you descend from the Chambaran plateau toward St Antoine-l’Abbaye, the descent becomes steeper, with the stony and uneven ground requiring constant vigilance. This route is not for the faint of heart, but it rewards those who persevere.

State of the Via Adresca: Today’s stage favors the paths, though they are very rocky:

- Paved roads: 7.5 km

- Dirt roads : 12.3 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

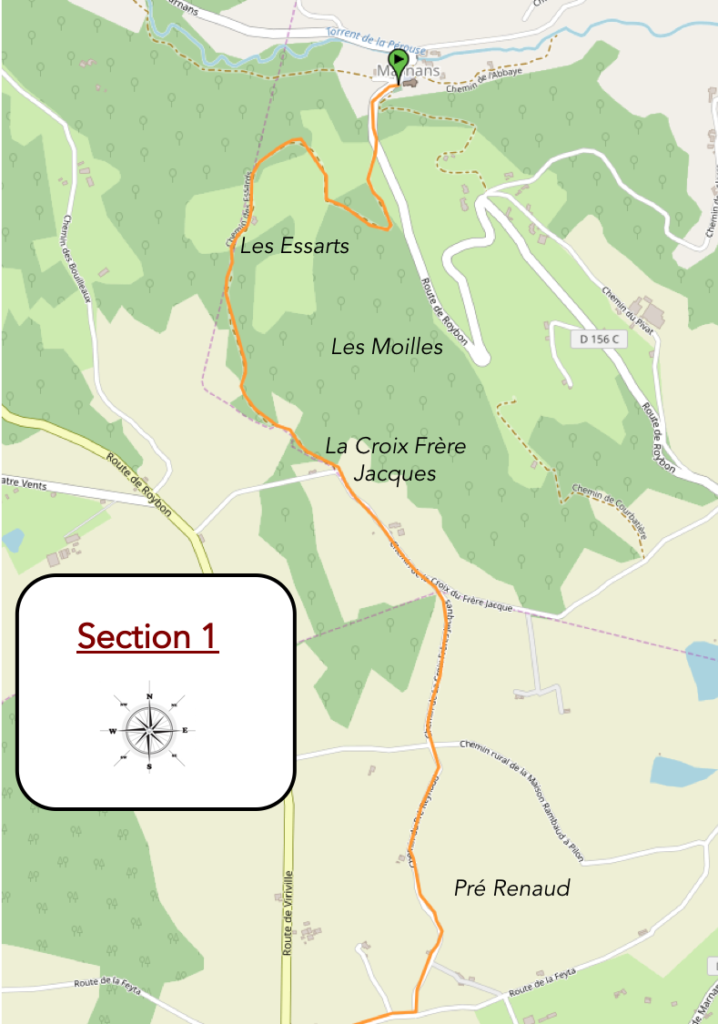

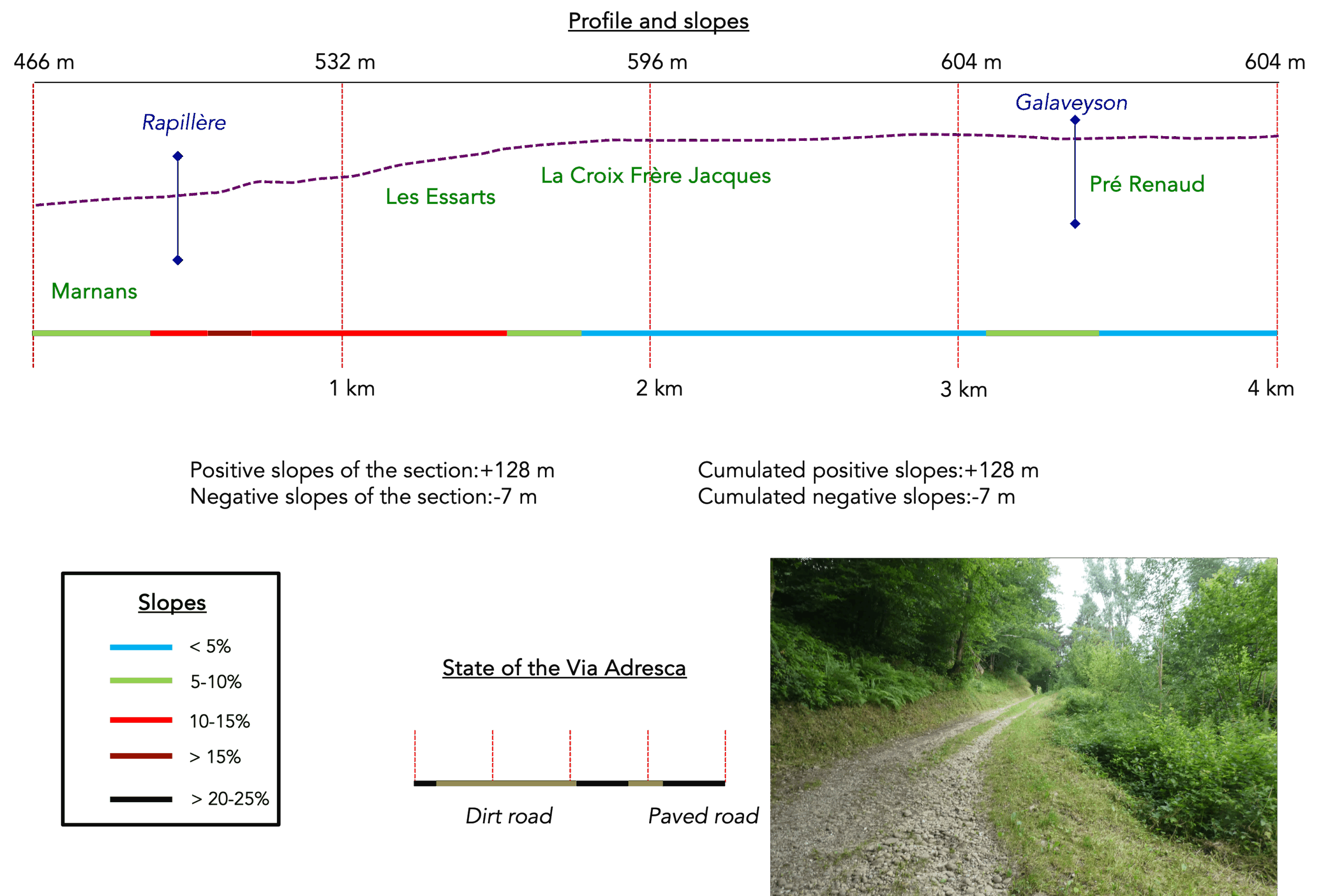

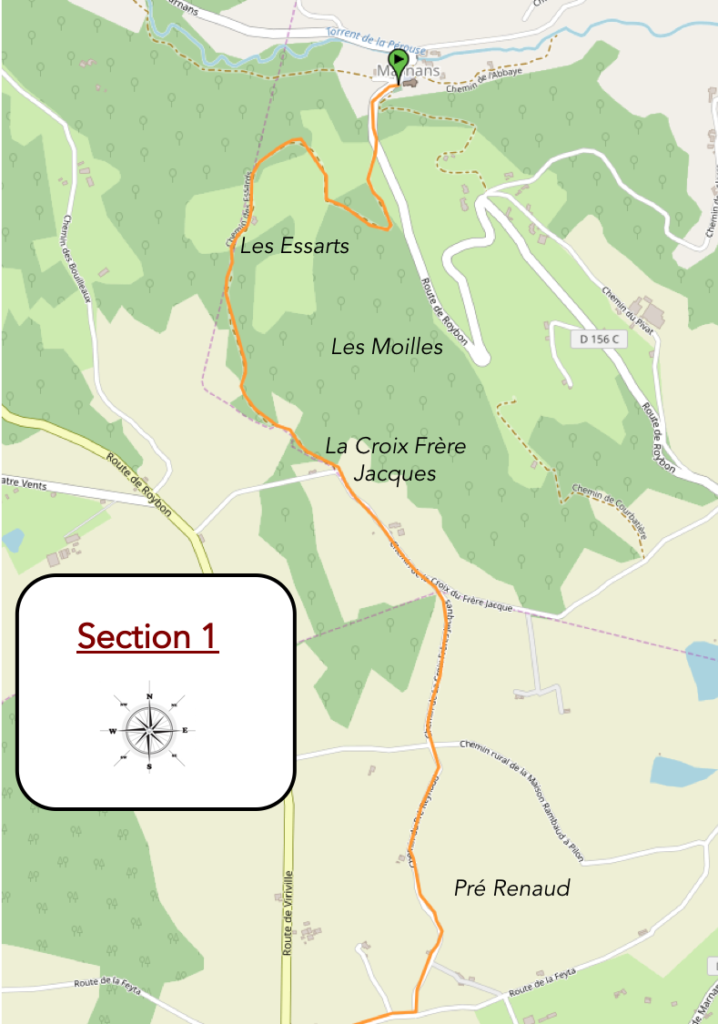

Section 1: Ups and downs from one dale to the other

Overview of the route’s challenges: no difficulties, except for the ascent to the high plateau, which often involves slopes close to 15%.

| There are no long distances to cover to leave the outskirts of Marnans. In truth, there are scarcely any. The paved road, pragmatic in nature, climbs unceremoniously behind the church, sneaking into the forest like a secret shared between the asphalt and the shadow of the trees. . |

|

|

| But the route does not linger; it wastes no time on the rough tarmac. At the first opening, the escape begins to take shape. A path discreetly veers off via the Chemin des Essarts, like a promise of freedom, into the dense undergrowth of the Grands Champs. |

|

|

| There, peaceful and discreet, meanders the Rapillière, a stream seemingly asleep in its dale, a quiet tributary of the Ologne. For a moment, you might have believed that the night had swallowed the stones, that the entire path had softened under the moonlight. Think again: the pebbles are still there, steadfast in their positions, scattered like invisible witnesses to the passage of time. |

|

|

| The path, in a slow and solitary dance, brushes against the stream, slipping between century-old oaks, chestnut trees twisted by the wind and bearing scars of old, maples with quivering foliage, and majestic beeches that seem to whisper secrets to those who know how to listen. Hornbeams are as rare as shooting stars on the routes to Santiago. Most often, there is only low hornbeam shrubbery clinging to the edges of embankments, tender and discreet. Further on, you will encounter some spruces, tall and proud, testifying to the ascent and the thinning air becoming cooler and rarer. |

|

|

| Here, undergrowth and thickets coexist in gentle anarchy. Bushes reign supreme, and the slope remains gentle, like a caress that does not impose its rhythm. When grass, nourished by the first warmth of spring, rises into a sea of green, the pebbles seem to timidly hide. You may then venture to brush against the coolness of the grass, skimming the earth without fearing the stones too much, so long as they no longer reveal themselves with every step. With one last glance, you glimpse Marnans, nestling at the bottom of the valley like a village asleep in a green embrace. |

|

|

| Soon, the path leaves the coolness of the undergrowth and heads toward the meadows, climbing through a clearing bathed in light. The slope becomes steeper, exceeding 15%, like a silent challenge to the hiker’s steps. |

|

|

| Higher up, a pisé farmhouse with walls of rolled pebbles stands solitary at the edge of the woods. Its stones, once witnesses to life, now seem frozen in time. The Essarts farm has likely heard no new voices for many years, its breath extinguished, erased by the passage of time. |

|

|

| There, the climb comes to an end. A wide dirt path, hardened by years and weather, stretches out before you. The clay, at times nearly loamy, clings to your soles, while chestnut trees begin to dominate the horizon, their branches outstretched like arms toward infinity. Oaks, beeches, and maples grow scarce, relegated to the background, while the chestnut tree, proud and conquering, reigns unchallenged, like a lord over his lands. The path stretches, indifferent. All the way to Ardèche and Haute-Loire, the chestnuts, like sentinels, will rule until the end of the route. |

|

|

| The path then crosses a high plateau, an open space where the land breathes and light generously illuminates vast clearings. Here graze Charolais cows, raised for meat, now far from their native land. Slightly smaller than their Aquitaine cousins, they graze peacefully under the watchful eye of ash trees, which are much loved by farmers. For near these giants, men are never far away. In the past, these ashes provided benefits to livestock, their seeds nourishing the herds. Today, the ashes dance in the wind, their branches swaying like large hands polished by time. |

|

|

| Higher still, the path opens onto La Croix de Frère Jacques, an isolated crossroads in the countryside where the wind plays among clusters of deciduous trees. A final breath of freedom before vanishing into the horizon. |

|

|

| The Via Adresca stretches further on the broad stony path, as if hesitating to leave this vast expanse before finally finding a paved road crossing the high plateau. Here, grass mingles with cereals under the protective shade of tall trees whose branches hold many secrets. |

|

|

| On this plateau, deserted by men, the rare houses hide timidly behind thick hedges. Here, the ancestral gestures of livestock farming persist in an almost intimate tranquility, and the land nourishes, however modestly, a few cereal crops. Nature seems to have found its fragile balance between the wild and the hands of men. |

|

|

| A little further on, the route leaves the asphalt to dive into a path of stones and small gravel. This path skirts fields of grain and expanses of corn with green and coppery leaves. The soil, a deep ochre, becomes ferruginous, imbued with the ancient spirit of the place. The crops are mainly oats and triticale, grown in this poor but resilient land, which offers all it can to those who know how to draw life from it. |

|

|

| Here, in this region, paths often transform: wide stone paths give way to patches of paved roads, a silent interplay between rusticity and modernity. Tractors, heavy and powerful, prefer smooth asphalt, avoiding marshy terrain where their wheels risk sinking into deep mud. |

|

|

| But this venture onto asphalt is short-lived. Very quickly, the path regains its independence, weaving through fields, climbing, descending, tracing its course through this unpretentious countryside. This is countryside in its purest expression: simple, serene, without unnecessary ornamentation. |

|

|

| At the top of the small hill, the road reappears, gentle and winding, through a varied landscape where crops compete for space, vying to dominate the meadows. The land here is more generous, creating harmonies of green and yellow. |

|

|

| Here, the Galaveyson stream cuts across the road like a demarcation line. This region is also rich in small ponds, mirrors of water that, unfortunately, remain out of reach of the track. It would have been pleasant to linger there, but the route has its own rhythm, not allowing detours for water. |

|

|

| The paved road continues, then crosses the hamlet of Pré Reynaud, only two kilometers from Roybon, like a promise of comfort before delving further into the dale. |

|

|

| Here you are on the Road of La Feyta. These « feytas » are moraine plateaus, placed like islands above the great plains of Dauphiné. Similar ones were encountered in Bièvre-Valloire, lands that, in addition to being cultivated, hide beneath their soil the pebbles, silent witnesses of ancient glaciers. The Via Adresca continues along the asphalt, crossing the D156 departmental road leading to Roybon. Then it takes the smaller road of Blain Haut, more discreet but equally imbued with the history of the place. |

|

|

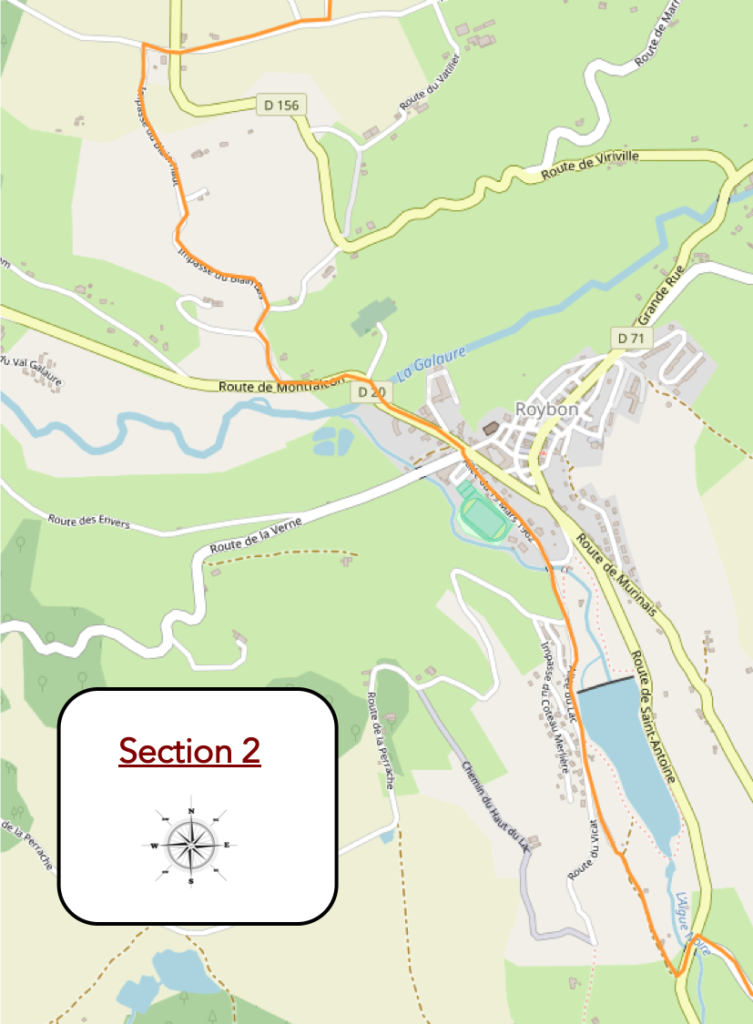

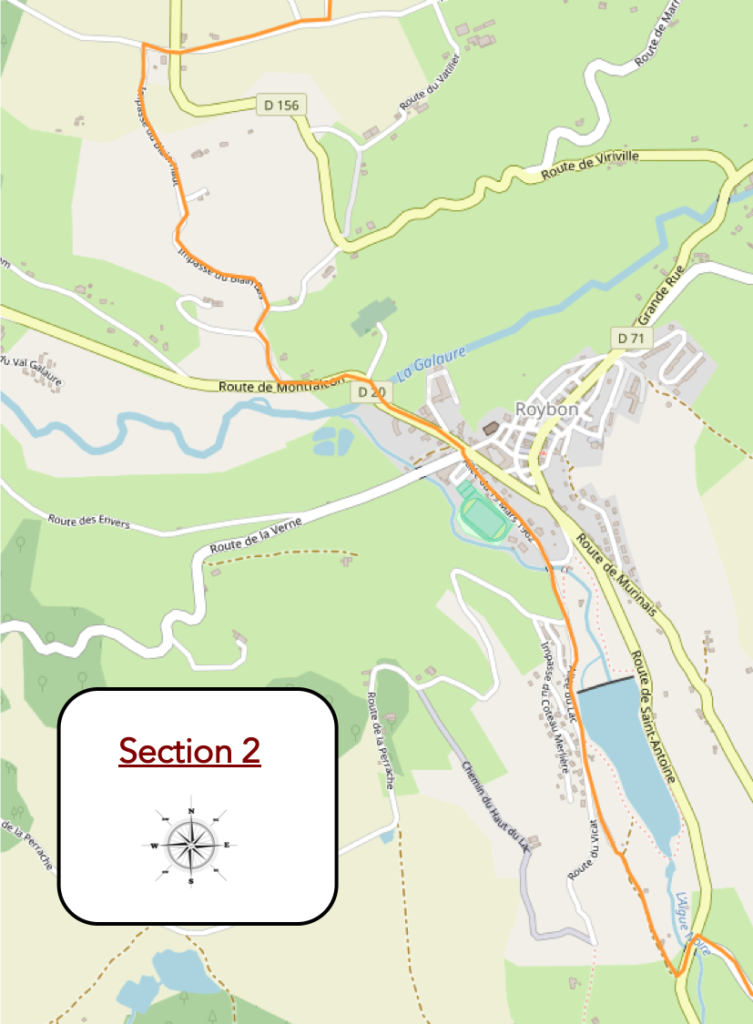

Section 2: A pause at Lake Roybon

Overview of the route’s challenges: no difficulty.

| The road soon expands at the place known as Le Blain Haut, winding through vast cereal fields where nature appears less elegant, more pragmatic, like a functional tableau. The fields stretch as far as the eye can see, bearing witness to a world where humans leave their mark on the landscape. The cereals ripple in the wind, but the horizon remains dry, dominated by a nature bent to the demands of agriculture. |

|

|

| Gradually, the road changes its tone, transforming before your eyes. It now plunges into a wilder setting, where hedgerows mingle with shrubs. The vegetation, less disciplined, seems to reveal another face of nature, more rebellious and untamed. Here, life appears in its rawest form, with every twig and branch struggling for its place in this imperfect world. |

|

|

| A bit further on, the route becomes more intimate, like an invitation to discovery. It leaves behind the asphalt of the road and dives into a path that unfolds among tall grasses, untouched by agriculture, like a secret corner of the world. Here, nature reclaims its rights, offering a sense of freedom, where one can almost hear the murmurs of a universe living to its own rhythm, unconcerned with human structures. |

|

|

The view, guided by the path, plunges below toward the small town of Roybon. From above, the village reveals itself like a pearl delicately nestled in its verdant setting, a jewel lying in a green jewel box, almost intimate in its simplicity. It seems suspended in time, a pause amidst the incessant flow of the surrounding nature, tranquil and almost secretive.

| The slope then becomes steeper. In this region, every path descending appears to follow a geological rule where pebbles reign supreme. Here, it’s not about small stones but pebbles of all sizes, smoothed over by centuries of natural history. Their roundness and soft sheen, almost soothing, testify to the patient erosion of the elements, a slow yet persistent dance that shapes the landscape. |

|

|

| The surrounding forests are dominated by modest yet proud vegetation: small, scrappy chestnut trees fight against the rush of time, while majestic and robust ash trees rise proudly skyward. A few sturdy and imposing oaks stand with great dignity, while slender maples trace a more delicate silhouette, offering a lighter counterpoint to the heavier trees. It’s a fragile balance where each species seems to play its role in this forest symphony. |

|

|

| Then, the path slopes more steeply, plunging into a dense undergrowth where the thickets grow wilder and more untamed. The atmosphere becomes stifling, as though nature intensifies under the pressure of the descent. The path winds between trees, descending into the vegetation to join the departmental road leading to Roybon, the town drawing closer, heralding the approach of a civilized world on the horizon. |

|

|

| The Via Adresca, true to its vocation as a historic route, quickly reaches the village entrance, offering those who follow it one last image of the countryside before transitioning into the settlement, like a passage between two worlds, two rhythms. |

|

|

At the edge of the village, the Galaure, much more than a mere stream, cascades joyfully, leaping and bounding over stones in a frenetic display of sound and movement that awakens the senses. It thrives at the heart of the landscape, adding a touch of life and vibrant freshness contrasting with the dryness of the surrounding agricultural world. The water, ever in motion, seems to embody the very essence of nature that resists and persists, joyful and free in its flow.

| Roybon, a small place of about 1,300 inhabitants, boasts all the necessary shops to meet the needs of its residents. Beyond its local activity, it is also a welcoming stop for pilgrims drawn not only by its tranquility but also by a curious symbol: a miniature replica of the Statue of Liberty. A nod to America, it also reflects the liberty of traveling, wandering, and flourishing under the skies of the Bas-Dauphiné. The small town stands out for its numerous houses built with rolled pebbles, silent witnesses of a time between the 18th and 19th centuries when local architecture took shape from the ground’s resources. The neo-Romanesque church, also built from pebbles, rises majestically, recounting its own story as a guardian of memories. With its intricate puzzle of smooth stones, it’s unmistakable: you’re in the Bas-Dauphiné, in Isère. |

|

|

The Via Adresca, moving away from the center, heads toward the Tourist Office. Formerly a train station, this site is a relic of a bygone era when rail travel reigned supreme. Decades ago, a railway connected Lyon to St Marcellin, winding through the Isère Valley. The train that once passed here continued to St Antoine-l’Abbaye. Known as the « Tram Line, » it was inaugurated in 1899 and permanently closed in 1936. Today, the railway is merely a hiking trail, but hope lingers: it might one day be revived. Even President Macron has pledged as much. Perhaps it will re-emerge as a high-speed train, who knows? The dreams of the past, shaped by rails and travel, could resurface in a more modern form?

| Roybon lies about seven kilometers from the Trappe monastery. The Via Adresca exits the locality, proceeding along the Allée du Lac, offering a tranquil prelude to the next section of the route. |

|

|

| Shortly after, it crosses the Aigue Noire, a stream aptly named. It winds and hides beneath thick thickets before merging with the Galaure, the stream running through the village. This modest, secretive stream seems to blend seamlessly with the surrounding nature, embodying a wild discretion. |

|

|

| The small road, which then follows the river, leads to the lake, a slightly elevated artificial reservoir that offers a picturesque view. |

|

|

| The road skirts the lake, peaceful and welcoming. Its serene calm makes it an ideal spot for relaxation, whether swimming, fishing, or paddle-boating, depending on the season. The shallow, clear waters murmur softly under the sun’s rays, and the surrounding scenery invites leisure. |

|

|

| But this road by the lake isn’t for hurried drivers. It leads to a dead end, while walkers can proceed without worry, crossing boundaries that cars cannot. Pilgrims pass freely as if the world belongs to them. |

|

|

| A path then descends toward the campsite, perfectly situated at the lake’s edge. In this particularly pleasant setting, the campsite blends seamlessly into the environment, offering travelers a haven of tranquility. |

|

|

| small paved road bypasses the campsite before crossing the Aigue Noire again, still hidden in the thickets, like a well-kept secret. |

|

|

| The Via Adresca, meanwhile, gains altitude, ascending the road leading to Chevrières, on the way to La Trappe, five kilometers further. Here, you won’t find the usual GR markers. Why? Because this isn’t a traditional GR but a specially arranged itinerary for Santiago, joined by other regional routes (PRs), often marked with yellow arrows. Still, the blue shell of Compostela will be your guide, your compass, the emblem of your inner journey. What you’re embarking on is a long endeavor, a voyage likely to etch itself into your memory, through the distinctive forests of Chambaran. |

|

|

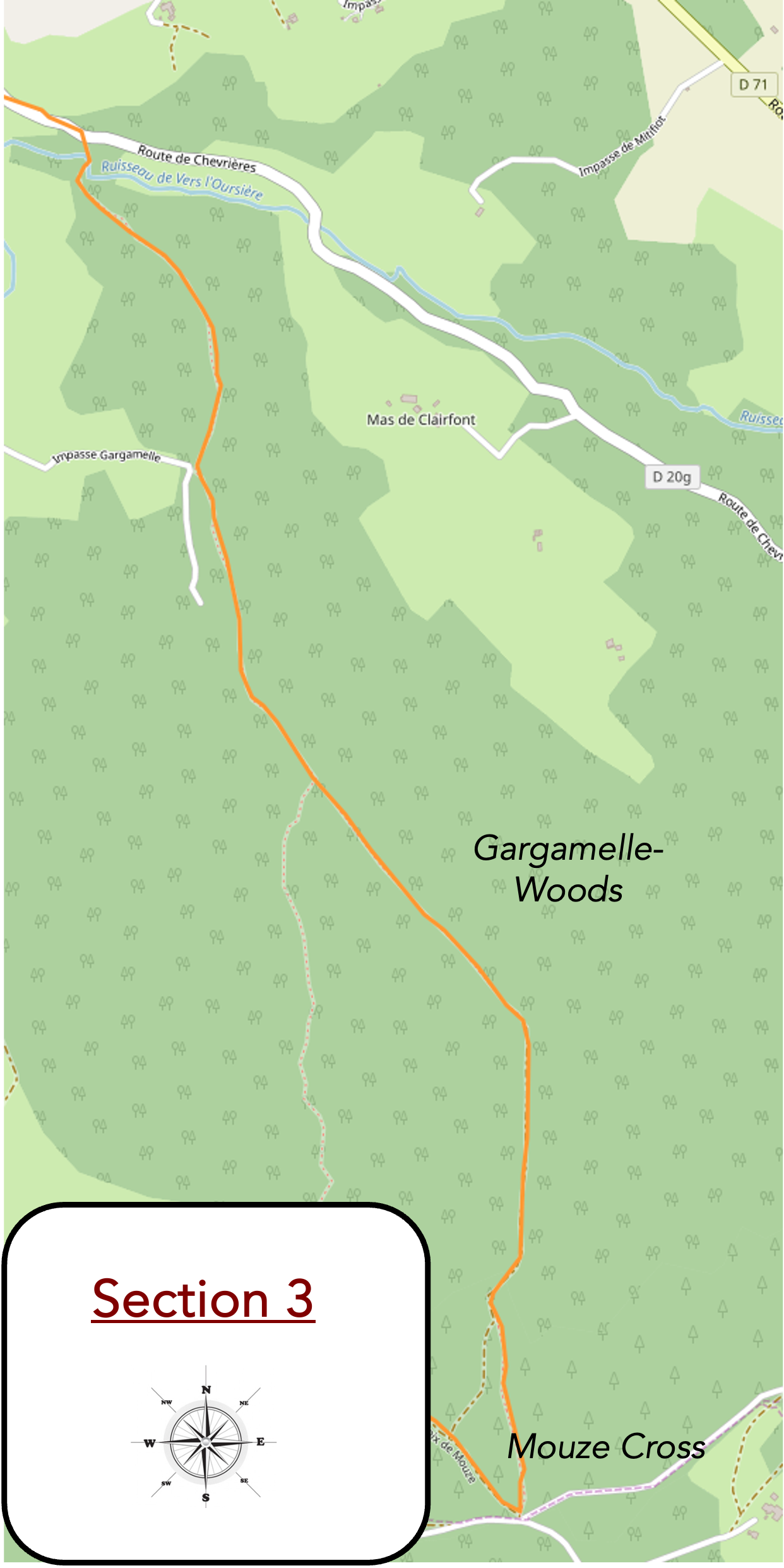

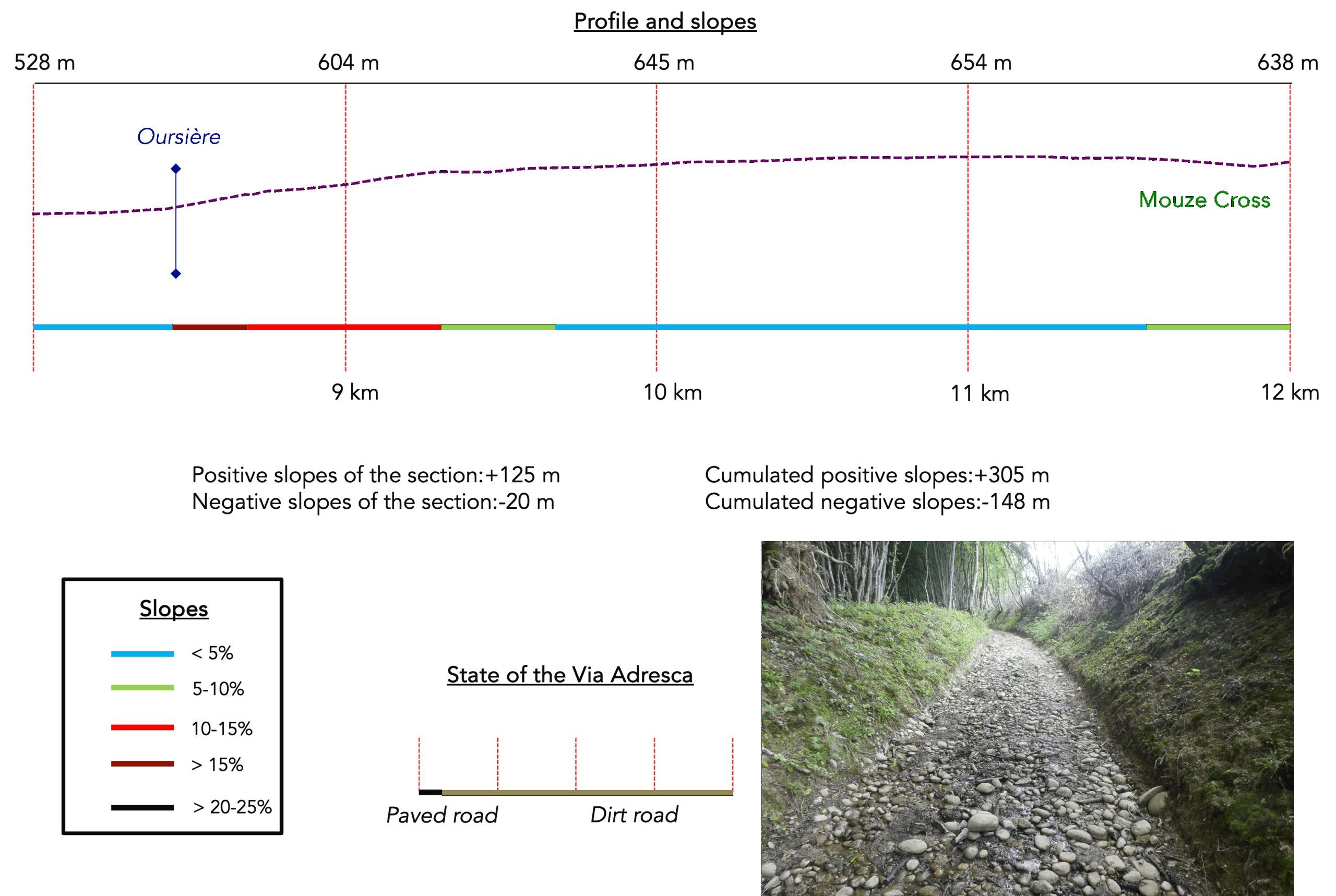

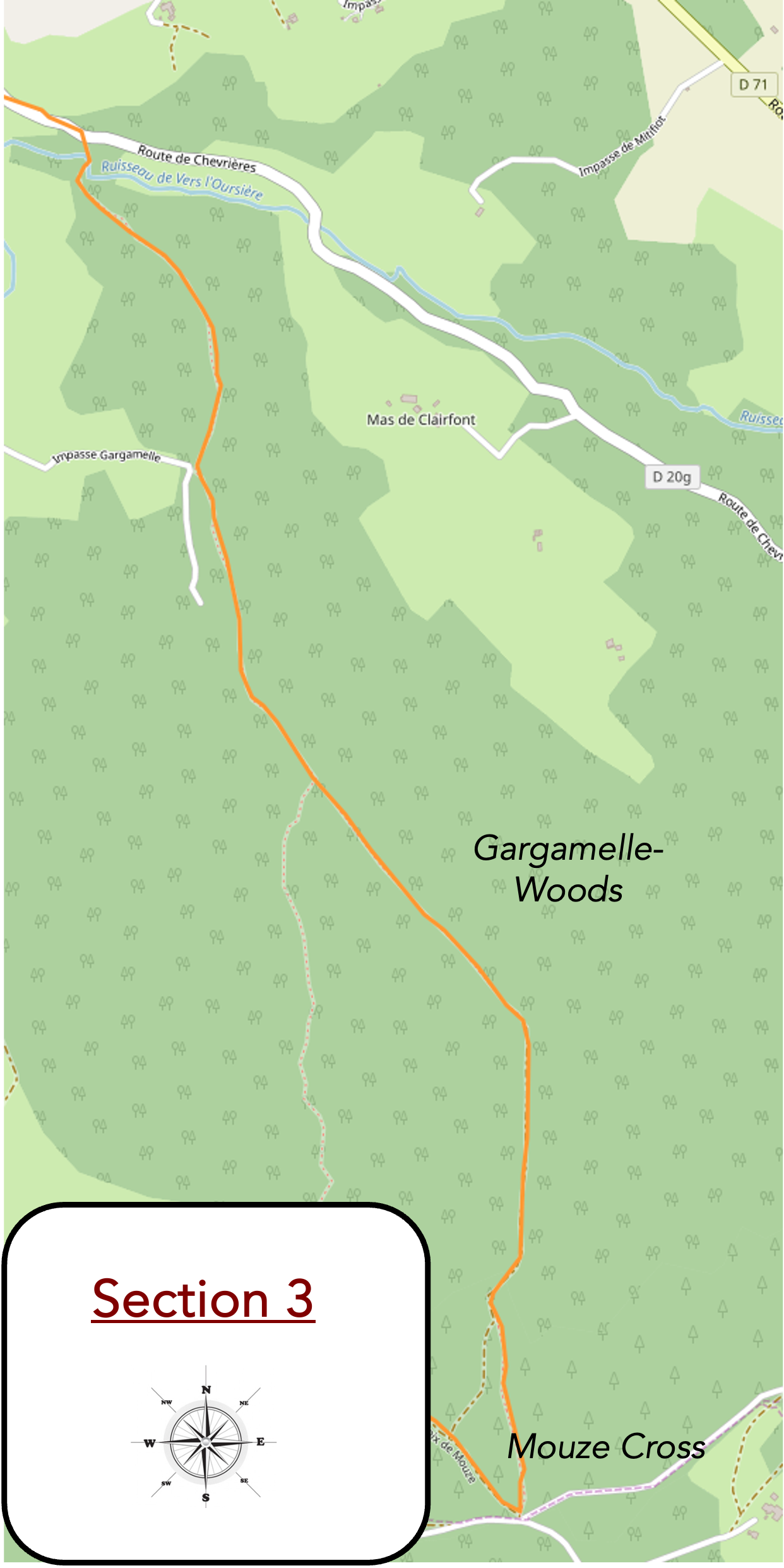

Section 3: Du côté de chez Gargamelle

Overview of the route’s challenges: Not too difficult, except for the fairly steep ascent on the pebbles at the start of the Gargamelle Forest.

| The Via Adresca barely strays from the road, almost imperceptibly, and soon a path appears, discreet, almost secret: the Path of Gargamelle. But why this strange name? Why evoke Gargamelle, the wife of Grandgousier and the mother of Gargantua, in a place where history seems to fall silent? In Provençal, the term “Gargamelle” means “throat” or “gullet,” but here, there is no gorge, not even a steep pass—just rolling pebbles, indifferent. Perhaps admirers of Rabelais, those who cherish his flourishing universe, wanted to insert this name into the scene with a touch of humor. Who knows? A wink at the wisdom of the giant of literature? The question remains open. |

|

|

| After this introduction, the path crosses the stream of L’Oursière, and it is here that you truly enter the Chambaran. This name evokes a vast expanse of wild land, marked by dense woods, abandoned moors, and heather that seem to fade into an eternal twilight. Although the deep ruts left by tractors testify to past exploitation, this part of the forest is still sparsely cultivated. As you climb, the environment becomes more rugged, the soil heavier, and the vegetation wilder. |

|

|

Quickly, the slope becomes steeper, a true scree slope in a way. The physical effort is felt. The pebbles, ever-present, seem to slip underfoot. Would Gargamelle, this imposing figure, have approved the idea of her name being associated with these unruly stones scattered across such steep slopes? It seems that nature itself wanted to play with etymology, for here, the land is anything but docile.

These pebbles, harder, more massive, and more imposing than those of the Bièvre, confront you with the timelessness of the place. Here, everything seems colossal, out of time, almost prehistoric. With every step, you almost expect to see, behind the tight trunks of the chestnut trees, the shadow of a dinosaur, a witness from another age.

| The Chambaran forests, like those of the Dauphiné, are dominated by chestnut trees, these giant leaves whose roots seem to take root in the ages. In certain regions, more than 90% of the trees are chestnuts, and you feel small under the imposing shade of these ancestral trees. Then come the pedunculate oaks, even more majestic in stature. Other species, such as black locusts, beeches, hazelnuts, ash trees, and maples, slip between these giants, like small touches of green, subtle yet essential shades. Among the conifers, the spruce reigns, while white firs, Douglas firs, and Scots pines have no say here. |

|

|

| Higher up, Gargamelle seems to drag her feet through thick, sticky mud, but this discomfort doesn’t last long. The wild boars, invisible yet present, seem to approve of this soaked earth, haunting it relentlessly. The path begins to clear, and the glade soon opens before you. The thickets, initially dense and impenetrable, give way to a tangle of brambles, but also to bushes of honeysuckle, hawthorn, dogwood, and broom. Ferns, vibrant green, rise here and there, adding a touch of freshness to the scenery. |

|

|

| The slope gradually softens, walking becomes easier, and you find yourself in a glade, an almost sacred space. Hunting, one can guess, must be practiced here, as evidenced by the palombières, these simple huts that line the edge of the woods. The wildlife is probably present, discreet yet omnipresent. |

|

|

| Here, hikers build small cairns, these piles of stones stacked simply. It’s not the lack of stones, of course, but rather the absence of travelers. Solitude seems to rule here, like an old friend passing through. The few promises of encounters are tenuous. If calm and tranquility are dear to you, then this road will enchant you. During our summer crossing, we met only about ten people in a week, a rarity, almost a luxury. This path, like a solitary meditation, unfolds beneath your feet. |

|

|

| Around a corner in the woods, in such an absolute silence it almost becomes palpable, the cattle are heard lowing. Then, the sound of a distant engine roars at the edge of the woods. The noise grows louder, sharper, until a man, mounted on his buggy, emerges from the meadows. He is a farmer, a familiar figure from the countryside, who, instead of the old shepherds walking for hours under the sun, now drives at full speed in his motorized vehicle. Times have changed. The kilometers of old, now devoured in the blink of an eye, have become memoriess. |

|

|

| This farmer, who lives in harmony with his animals, raises magnificent cows, these majestic creatures with golden coats and sculpted horns, grazing the grass with an appetite that seems infinite. Blonde d’Aquitaine, Charolais, Limousin, Aubrac, and the magnificent Salers, with their lyre-shaped horns, find their happiness in this lush meadow. But this beauty of nature has its downside, and the farmer, with a hint of disillusionment, reveals that despite their splendor, these cows, whose existence seems like a living poem, are sold for the same price as Holstein cows, whose lives consist only of dragging their weight over often barren pastures. What mockery! What injustice in the commercial world, which, in its cold logic, levels everything, erasing the difference between beauty and banality. |

|

|

| The ascent is now over, and you have reached the high plateau of the Chambaran, where the landscape seems to open up infinitely. Gargamelle and her mystery fade behind you, giving way to a new space, that of the Secret Wood. The inhabitants of these lands have a definite taste for poetry, as evidenced by the name of this mysterious wood. |

|

|

| Here, the Via Adresca runs quietly flat, winding through a majestic and serene forest, of almost supernatural beauty. But, beneath the softness of this setting, the clayey, refractory soil resists water, creating puddles where water lingers without ever evaporating, even during dry spells. The tracks left by tractor wheels have dug these pockets of stagnant water, making the passage difficult, and the nature itself is both harsh and generous. |

|

|

| Faced with this challenge, hikers, for comfort, have created detours, avoidance areas where the water does not impede their progress. You might wonder if the wild boars and roe deer also use these secret passages, like invisible accomplices to the travelers. |

|

|

| The path continues, weaving through the trees, between gnarled trunks and dense foliage. And, a little further on, it finally reaches the Secret Wood. It is here that, alone, each direction sign becomes a beacon, a precious guide in this vegetal universe where one could easily get lost. They are lifebuoys, reassuring signs: no, you are not lost. Here, the path leads to the Mouze Cross, a landmark only a kilometer away. |

|

|

| The forest, however, remains unchanged, faithful to itself, as beautiful, dense, and serene as ever. It is neither disfigured by the passage of time nor affected by man, but simply lives, in all its simplicity. It is rich with chestnuts, a flourishing vegetation, and a peace that is almost tangible, like a place out of the world. |

|

|

| But sometimes, in this essentially leafy landscape, a pine rises, bold, defying the other trees, claiming its place among them. It stands there, solid, firmly rooted in the earth, to prove that it too belongs in this majestic nature. |

|

|

| Then, around a small clearing, the light appears, slipping between the trees. A moment of light, a respite, before the path plunges back into the quiet shadow of the forest. It’s a strange paradox. Here, in the forest, the pebbles have disappeared, but the land is still marked by traces of ancient glacial moraines. The question remains: were they cleared by man, or did geology work its magic, bringing these stones to the surface where the soil is less inclined? |

|

|

| The path eventually reaches the Mouze Cross, this point of convergence, a stone’s throw from the Trappe, a beautiful wooden cross marking the end of a spiritual and geographical adventure. Christianity, like an obvious conclusion, takes its place after crossing these sublime, mystical, and wild forests of Chambaran, imbued with a raw and essential beauty. |

|

|

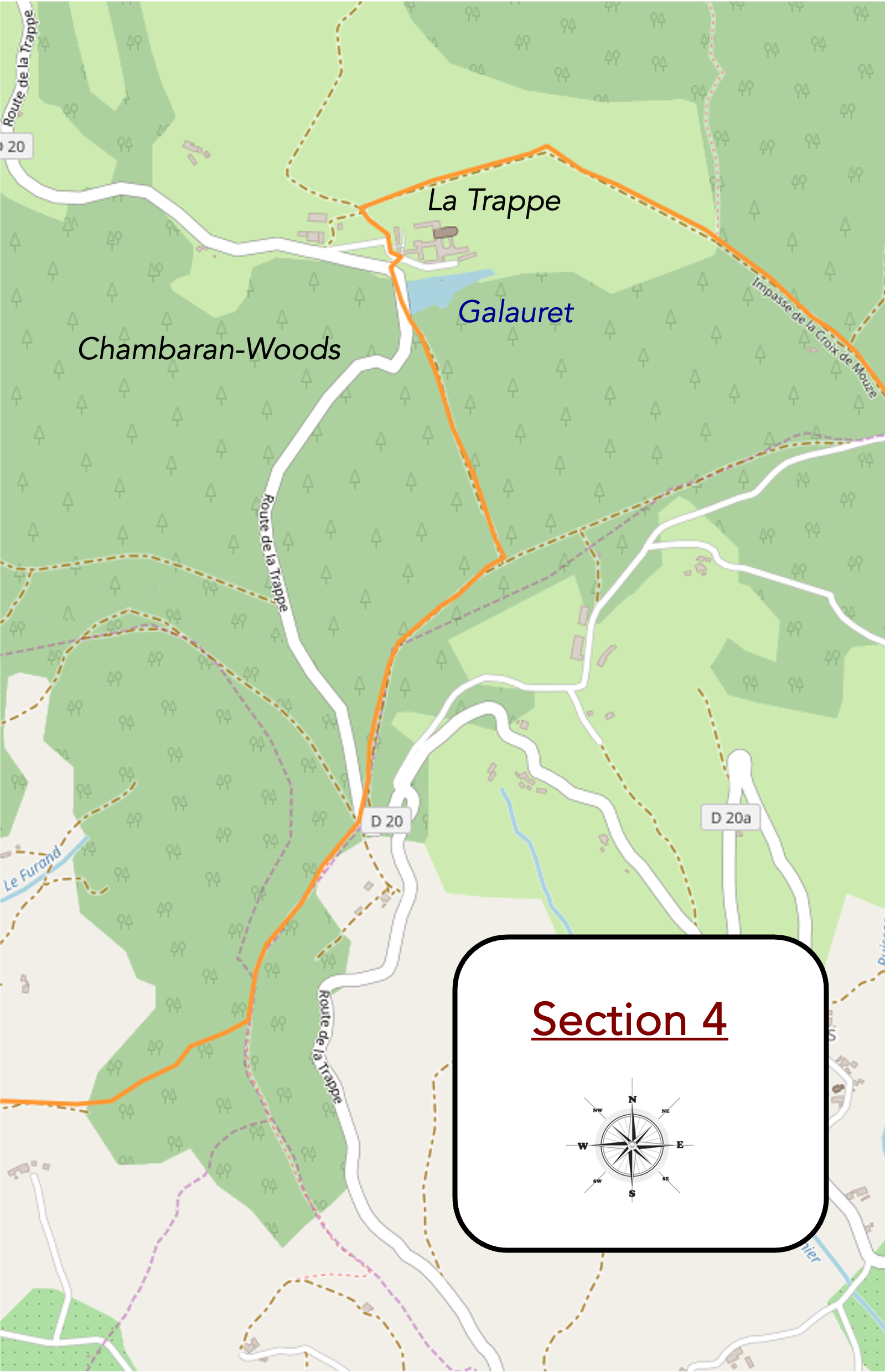

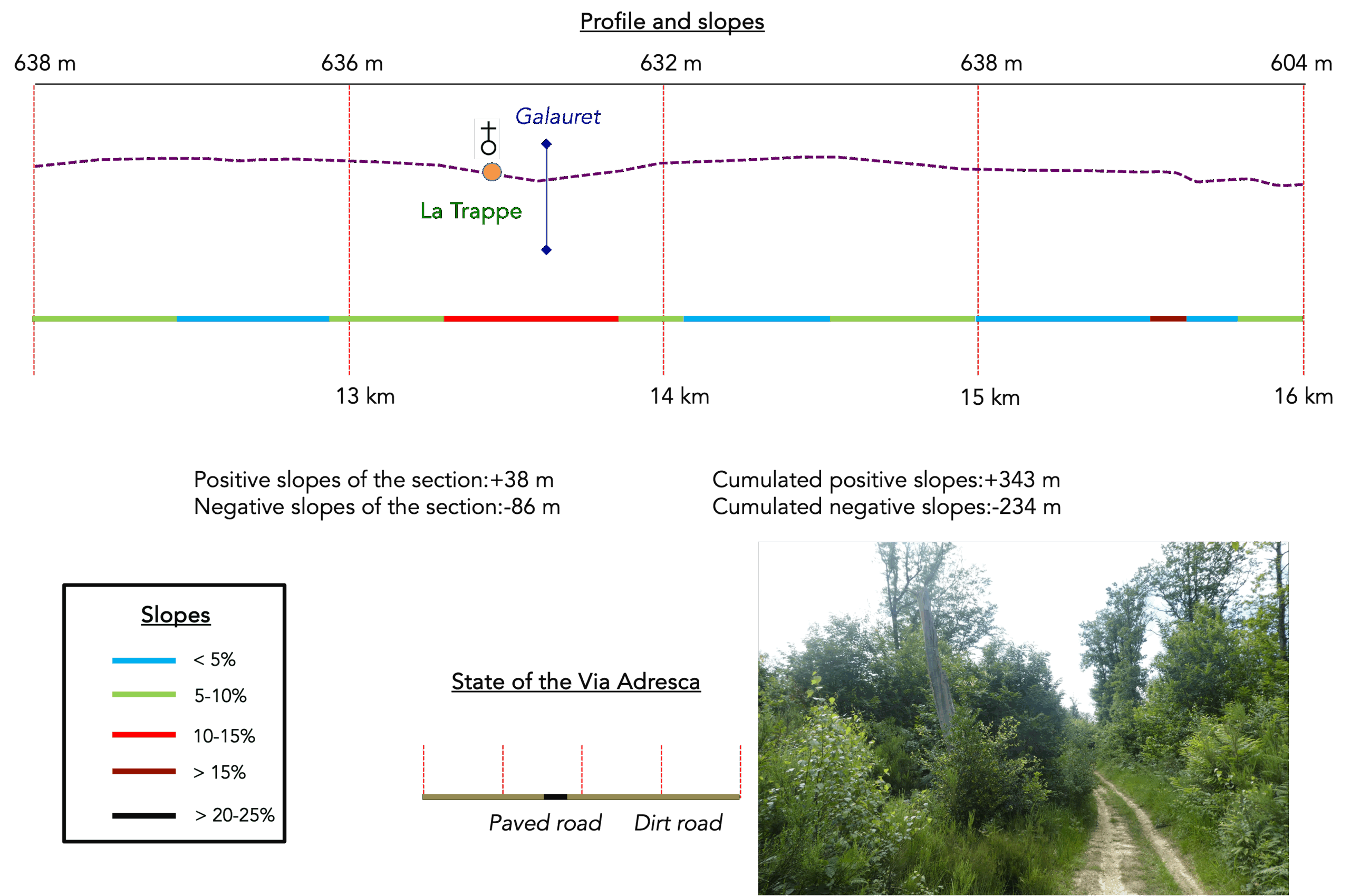

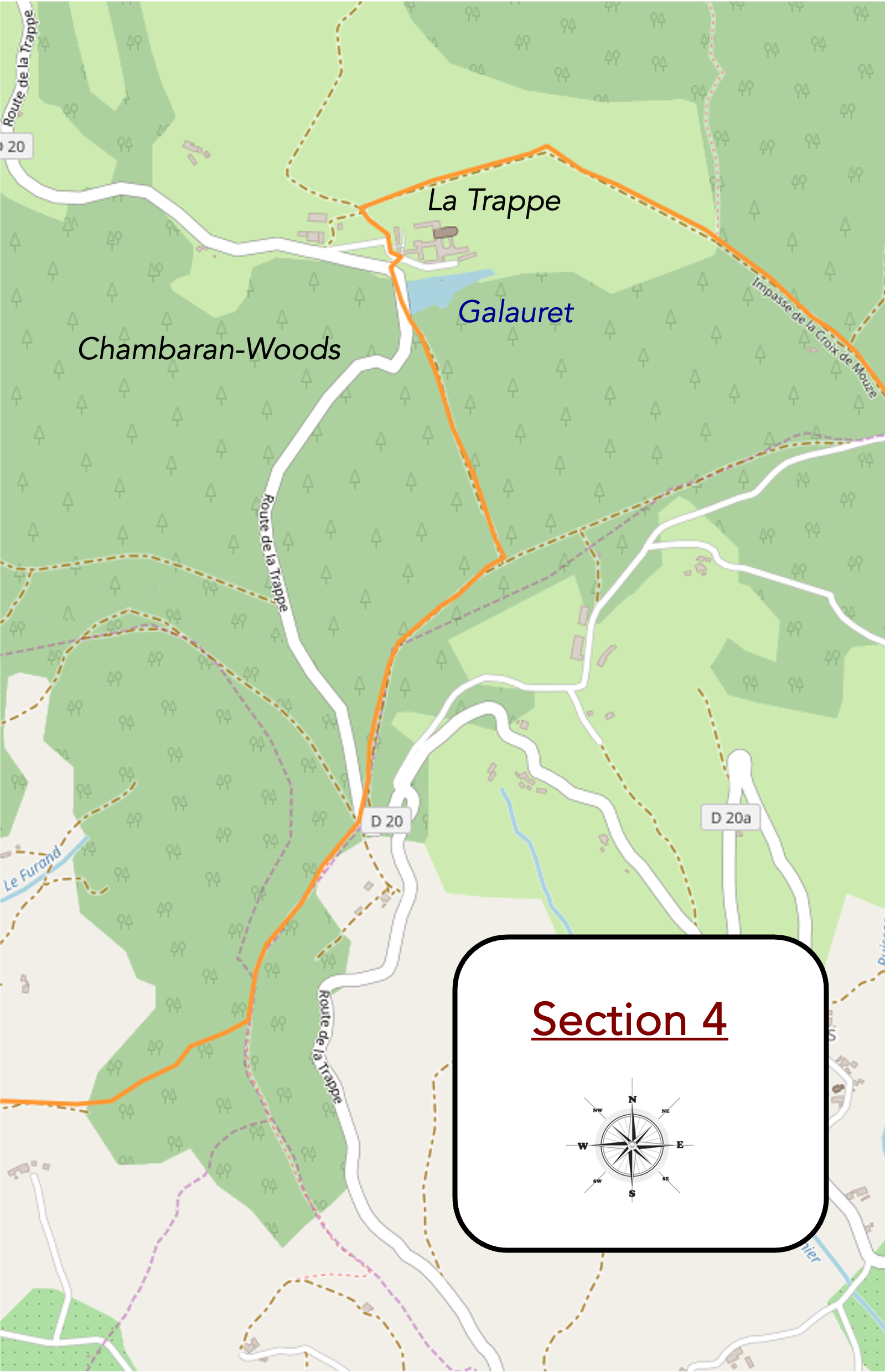

Section 4: La Trappe on the Chambaran hills

Overview of the route’s challenges : it constantly fluctuates, but in a rather comfortable manner.

| At Mouze Cross, a small paved road unfolds, but the Via Adresca does not linger there. It suddenly takes a sharp right onto a wide path that winds through the forest. Here, the pines begin to multiply, their trunks rising straight towards the sky like a silent army, blending with the light filtering through the treetops. |

|

|

| Approaching the edge of the forest, the path leads to a strange place called Le Mur de la Trappe. However, despite the intuition inspired by this name, no wall appears on the horizon. Is it an illusion, a remnant of the mysteries of Gargamelle, or perhaps a memory of an old wall once built to demarcate the domain of La Trappe? The imagination here takes precedence over reality ? |

|

|

| Leaving the shadowy woods to enter the corn and wheat fields that stretch as far as the eye can see, the abbey of Chambarand suddenly reveals itself, emerging in the valley, majestic and tranquil, like a well-kept secret from the past. It is here, in the heart of the countryside, that La Trappe, in all its discreet splendor, makes its appearance. |

|

|

| The path becomes rockier, as if the stones themselves were trying to slow the travelers’ steps. A hedge of brambles forms along the edge, and with each slope, pebbles reappear, as inevitable as the rain that washes the earth, continually unveiling these still witnesses of time. This subsoil, no doubt, hides an infinite reserve of pebbles that, with the changing weather, surface like the memories of a bygone era. |

|

|

| The path quickly approaches the abbey. Initially hidden within the natural surroundings, the abbey seems like an apparition, a solitary building that, beyond its stone walls, embodies the harmony between man and nature. The building imposes, without ostentation, its tranquility and majesty, like a silent beacon in the forest. |

|

|

| The path soon reaches the gate of the Abbey of Notre-Dame de Chambarand, a place steeped in history and spirituality. Founded in 1868, the abbey was extinguished in 1903, a victim of the suppression of religious congregations, before being reborn in 1931 thanks to the installation of Trappist nuns, fervent Cistercians who revived the monastery. |

|

|

| A bit of history is needed to understand the soul of the Trappists. It was in the 11th century, in the Orne region, at Soligny-la-Trappe, that the monastic movement began. The Abbey of La Trappe, initially part of the Cistercian Order in 1147, has traversed centuries and reforms. In the 17th century, as fervor for the monastic rule waned, Trappism was born, a strict observance that returned to the rigors of the old ways. Monks and nuns, devoted to a life of contemplation and prayer, live according to the rule of Saint Benedict, which governs every aspect of their existence.

But the French Revolution, in its destructive surge, did not spare these refuges of peace. Several hundred Cistercian monasteries were destroyed, and the Trappists, persecuted, took refuge in Switzerland, Germany, and even Russia. It was only after Napoleon’s fall that the Trappists were able to return to France. In 1814, the order was reestablished at La Trappe, and its influence spread across the world, giving rise to many abbeys. Today, the Order of the Strict Observance has more than 2,600 monks and 1,800 nuns, spread across ninety-six abbeys.

The Abbey of Notre-Dame de Chambarand, located in the tranquil valley of the Isère, is the last active Cistercian abbey in this region. Its architecture, shaped from rolled pebbles, perfectly integrates into the natural environment. Far from the famous beers and cheeses produced in other monasteries, here, the nuns dedicate themselves to prayer, craftsmanship, and the sale of products from other abbeys. Thirty-four sisters live here, in a simple yet profound existence, in communion with nature and spirituality. |

|

|

| A path in the grass, soft and winding, gently descends beneath the Abbey of La Trappe, guiding the steps towards a lower, more secret world. It winds through tall grasses and wildflowers, carrying the walker into a deep tranquility. |

|

|

| Soon, it reaches the road, just below the monastery, where the outside world seems even more distant, almost unreal. It is a return to the concrete, but a return to a peaceful solitude, far from human agitation. |

|

|

The Via Adresca, following its tranquil course, runs alongside the Galauret stream, which stretches here like a thin river, or rather like a serene pond. The water spreads out into a large calm surface, reflecting the trees and the sky like a mirror, and is connected to several ponds hidden beneath the lush vegetation. Above, the abbey watches over, imposing and silent, while the peace of the place fills the soul.

| From the pond, a path gently slopes up, initially stony, slowly climbing into the Bessins forest, which seems to close in around the traveler like a green cocoon. Each step, each breath, seems to merge with the tranquil harmony of this enclosed world. |

|

|

| As you progress, the pebbles disappear as if by magic, swallowed up under the shadows of the pines, oaks, and chestnuts. The ground becomes softer, less harsh, but the tracks left by the tractors, like invisible ruts, remind us that this forest, as wild as it may seem, bears the marks of man. The Chambaran, still, plays its strange and rhythmic waltz between pebbles, clay, and harder ground, like a memory of raw nature. |

|

|

| Soon, the path leads to a place called Forêt de Bassins, six kilometers from St Antoine-l’Abbaye. |

|

|

| Here, the foresters have taken control of nature, clearing the area and offering an open view of a sea of tall chestnuts, dotted with rarer pines and ashes, also drawn to the light, preferring to thrive away from the shadows of the other trees. These are proud species, but they seem to be fighting for space, seeking their place under a clear sky. |

|

|

| The path, however, leaves the forest at one point and makes its way toward the road to Roybon, which also winds near La Trappe. This is not a harsh exit from the woods, but rather a gentle encounter between nature and the traces of civilization. |

|

|

| At this precise moment, the hamlet of La Blache is very close, but the route does not lead there. « Blache, » a name that resonates like an old key, comes from Gaulish and means « oak. » It is a name frequently found in the region, a tribute to those places where the brushwood was cleared, rid of its oaks. These lands, freed from their heavy shadows, now give way to light and air.

The path then resumes its climb, still stony, but lighter this time, gently rising toward the forest, following the meadows and woodlands. Each step seems to rekindle the desire to move forward, like an invitation to blend even more with nature, to become one with it. |

|

|

| The forest, at this point, lightens, as if it has decided to grow less densely, allowing the air to breathe. You can sense that man has passed this way, that the pruning shears of deforestation have left scars on the top of the hill. The earth hesitates between deep ochre and dirty gray, creating a somewhat harsh backdrop on this clay path, which remains fairly soaked, like a damp memory of a recent rain. |

|

|

| Here, the chestnuts, ashes, and other species take full advantage of this open space. They stand proudly, their branches extended like welcoming arms, savoring every ray of sunlight that finally reaches their ground. The horizon seems wider, freer, without the heavy shade of the old forests. |

|

|

| And then, one last dance with the pebbles of Chambaran. A final contact with these stones that follow you throughout the day, before the path completes its journey through the forest and finally exits. |

|

|

| Then, suddenly, everything changes. You’ve spent most of the day in dense, mysterious, magnificent forests. But now, the world before you is one of gentle, light hills that seem to embrace the sky. Where the earth blossoms, the curves of the horizon sketch peaceful, almost serene landscapes. Some undergrowth still remains, scattered here and there, but now it is the fields that dominate the landscape, a living mosaic of agriculture. When you’ve walked alone through these deep forests, and now return to the sight of the fields, there’s always a kind of relief, as if you can finally breathe more freely, a little closer to humanity. |

|

|

| Finally, humanity, as they say. The path descends, initially steep for a short stretch, before becoming gentler and calmer, winding between tall grasses and pebbles, all in softness. Not a tree, or almost, just meadows that stretch out and some cornfields that punctuate the space. |

|

|

| At the end of the descent, the earth has changed. The path becomes almost sandy, soft underfoot, like a promise of lightness. It then opens onto a small paved road, very close to La Grange Bernier, a simple, almost intimate place, where one immediately feels at home. |

|

|

| The course continues its journey, this time following the main road that climbs gently toward a crossroads, the one that leads to Château Renard. |

|

|

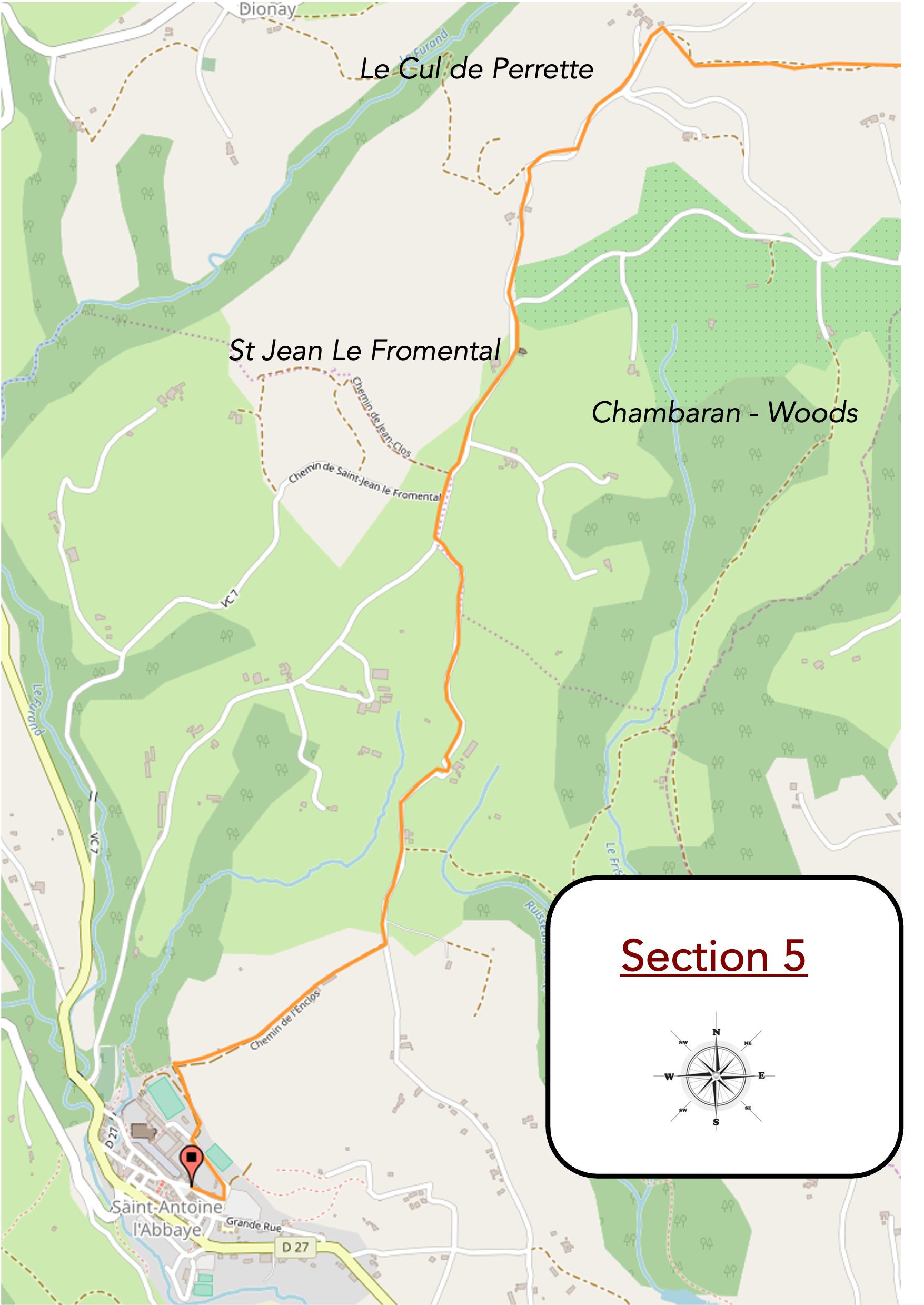

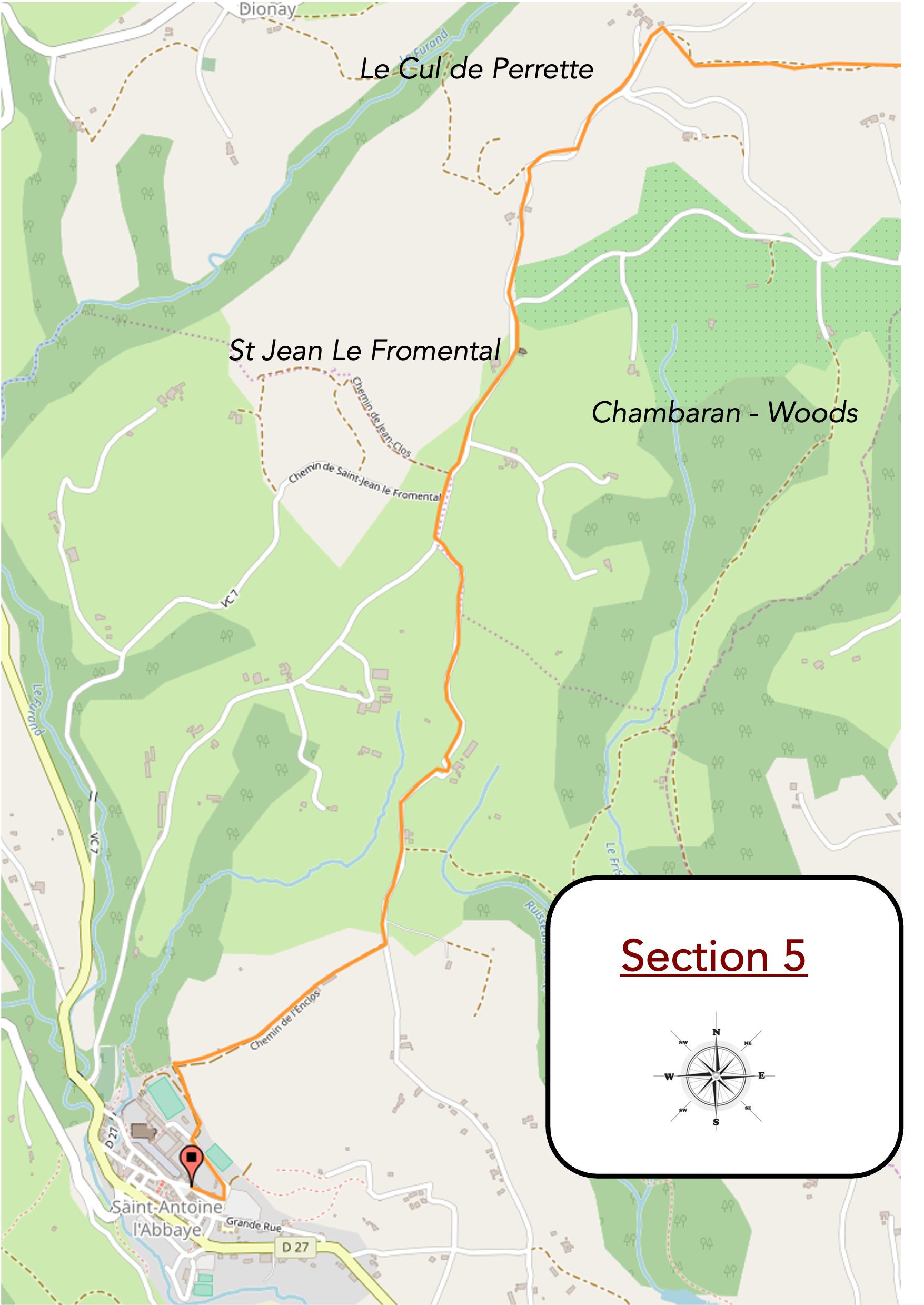

Section 5: On the way to St Antoine-l’Abbaye, another gem from the Middle Ages

Overview of the route’s challenges: a few beautiful slopes, but mostly downhill. The gradient rarely exceeds 15%.

| The road slopes up slowly, winding up the hill. Although the slope is moderate, it still requires some effort. Not extreme, but enough to advise motorists to have good equipment in case of snow. We are here at less than 600 meters in altitude, in a region where, in winter, nature becomes harsher. |

|

|

| Upon reaching the top of the hill, the road descends almost as steeply, following the contours of the small hills that roll in undulations. Before you, the horizon widens to reveal the Vercors, imposing and distant, standing proudly on the other side of the Isère valley. |

|

|

| Soon, the road reaches a place with a curious name: Le Cul de Perrette. A name that, though not poetic in itself, still seems imbued with the history of the land, like a forgotten relic from ancient times. |

|

|

| The road continues its descent through the countryside, which unfolds generously, between walnut trees. The trees seem to stretch endlessly, lined up one after the other like soldiers ready to march, but here, it is the softness of nature that reigns. You walk alongside the famous walnut orchards of Grenoble, these walnut trees that line the landscape for miles, shading the earth and the souls of those who gaze upon them. |

|

|

| Then, slowly, the road climbs again, a small ascent that briefly takes you away from the softness of the valleys. |

|

|

| At the bend in this climb, you pass the chapel of St Jean-Fromental, a peaceful place where time seems suspended. The chapel, simple yet graceful, has been known since the Romanesque period, when it was part of the possessions of the Antonins of St Antoine-l’Abbaye. The typical Romanesque archway bears witness to this ancient time, but the chapel has been transformed over the centuries. However, its soul remains intact. Classified as a Historic Monument, it still houses a bell from the 15th century, which rings the services every Sunday in summer, offering a gentle and familiar resonance to the souls of pilgrims and locals alike. |

|

|

| Just beyond the chapel, the road climbs again for nearly half a kilometer, to reach the top of the hills that overlook St Antoine-l’Abbaye. The ascent is long, but the rural landscape that gradually unfolds offers a reassuring tranquility, almost divine. The soul rests here. |

|

|

| At the summit, the tarmac gives way to a dirt and gravel path that gently descends the opposite side of the hill, offering a new perspective on the valley. |

|

|

| The countryside that stretches before you seems straight out of a postcard, bucolic and serene. Rows of vineyards emerge between the walnut trees, like a wink to local traditions, while the large meadows sway under the light breeze. |

|

|

| Lower down, the road returns to its tarmac surface and resumes its winding rhythm, snaking between farms and fields that border the landscape. It sways, like a thread of Ariadne woven between the hills. |

|

|

In this region, the small hills connect endlessly, creating an infinite dance. The road, meanwhile, gently winds between them, like a melody you could listen to without ever growing tired.

| Soon after, the road begins a slight ascent, almost imperceptible, on a surface that oscillates between gravel and tarmac. |

|

|

| This hesitation of the route seems to announce its approach to the end, a final effort before reaching the place called L’Enclos, the last stop before the final point of this stage. |

|

|

| There, the tarmac road, marked by the passage of time and seasons, continues. It passes in front of a self-service fruit and vegetable stand set up by a nearby farm. |

|

|

| From the farm, a bumpy, weathered path begins the descent toward St Antoine-l’Abbaye. |

|

|

| The slope becomes steeper, requiring some vigilance. At the end of the valley, the abbey slowly reveals itself, like a treasure still distant. The path, clearly cleared by patient hands, progresses toward the village with calm determination. |

|

|

| And then, suddenly, the eye is struck, almost dazzled, by the majesty of the place. The imposing grandeur of the abbey dominates the landscape, like a sentinel frozen in time, a silent guardian of the history of the land. |

|

|

| The route crosses the abbey’s gardens, now converted into a public park. Once, these verdant spaces were part of a vast monastic complex. The buildings, remodeled in the 17th and 18th centuries, bear witness to the glorious hours of the Antonins before their decline. Here stood the abbot’s house, the large cloister, the refectory, the libraries, the infirmary, the stables, and, of course, these carefully tended gardens. The shadow of the past still lingers in this harmonious layout, even though time and history have redefined their use. |

|

|

| At the entrance to the small town, the buildings of the Tourist Office and the House of Tourism and Heritage welcome visitors. These modest yet welcoming places serve as a bridge between the past and the present, inviting all to dive into the fascinating history of the abbey and its surroundings. |

|

|

| Crossing a baroque gateway embedded in a neighboring house, you emerge into a large, rectangular, shaded, and peaceful square. The cafés and small shops blend discreetly into the architecture, extending the atmosphere of serenity that emanates from the abbey’s annex buildings. Here, the whisper of the past and the breath of the present intertwine in a gentle and timeless harmony. |

|

|

|

|

| At the heart of the founding stories of St Antoine-l’Abbaye stands a notable figure: Jocelin of Châteauneuf. Having miraculously been healed by Saint Anthony, Jocelin undertook a journey to the Holy Land to bring back the relics of this venerated saint. This act of gratitude became the epicenter of a series of events that would forever mark the history of the abbey. By papal order, the relics were entrusted to the monks of the abbey of Montmajour, near Arles, and transported in 1088 to St Antoine, where the construction of the abbey began, a place suitable for worship. The arrival of the relics coincided with a troubled period: the emergence of the « holy fire », a horrific gangrene caused by rye ergot. This epidemic, previously mentioned in an earlier stage and also along the Via Podiensis between Auvillar and Lectoure, became the breeding ground for the Order of the Antonins.

In 1191, a conflict broke out between the Benedictines, already settled, and the Antonins, newly arrived, over the management of alms. The latter demanded an independent chapel, which the Benedictines firmly opposed. The rivalry took an architectural turn, with the Benedictines enlarging the church, while the Antonins were granted permission to build a modest chapel. Behind these religious disputes lay struggles for power and revenue, inherent to the religious institutions of the time.

However, the Antonins quickly gained the upper hand. By the end of the 12th century, they had established nine commanderies in the Dauphiné and had even expanded into Hungary. At the beginning of the 13th century, they achieved independence from the Benedictines by adopting the rule of the Canons of Saint Augustine. With this autonomy, they built an impressive hospital, which was unfortunately abandoned and later destroyed. Tensions with the Benedictines reached a climax when armed men, raised by the Antonins, forced the Benedictines to leave St Antoine. This coup allowed the Antonins to become the undisputed masters of the site. The quarrels extended to the relics: were they truly here or in Arles? In 1297, Pope Boniface VIII ruled, compensating the Benedictines and elevating the priory to the rank of abbey. With this status, the abbey began a major reconstruction, blending successive architectural styles. Around 1400, the nave was vaulted. The Wars of Religion and the French Revolution also left their mark, with alterations, destructions, and plundering.

The decline of the Antonins accelerated at the end of the 18th century, largely due to the disappearance of the « holy fire ». Without this terrible disease, their raison d’être vanished. In 1777, the Antonin order dissolved, and the buildings were handed over to the Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem, who did not stay long. The Revolution hastened the dismantling of the abbey: its property was sold, and the last inhabitants, the canonesses, were expelled in 1792. In the 19th century, the abbey experienced a brief revival when Jean-Claude Courveille acquired part of the buildings to establish a school. In 1840, thanks to the intervention of Prosper Mérimée, the abbey church was classified as a historical monument. Today, although stripped of its former splendor, it remains a precious witness to history, occasionally hosting religious services. Attached to the diocese of St Marcellin, the church continues to preserve, in the silence of its walls, the memory of past centuries. |

|

|

| The abbey is an architectural masterpiece that, at first glance, seems to embody the elegance of the flamboyant Gothic style. However, it reveals a fascinating blend of various styles, the product of successive periods of construction and restoration. This monumental building, listed among the Historical Monuments, imposes itself with its austere yet refined silhouette. The sculpted portal, a true lace of stone, first captures the eye with its precision and richness. Once inside, the nave, soaring and solemn, naturally leads the eye toward the altar. It is here, at the heart of this sacred grandeur, that the relics of Saint Anthony, the thaumaturge, rest. The whole, with its majestic facade, welcoming forecourt, monumental portal, and grand staircase, gives the abbey an allure that captivates and commands respect. |

|

|

| The treasures it houses are equally impressive. The murals, though relatively recent in their execution, seem imbued with a timeless patina, as if the walls themselves had absorbed centuries of history. The 17th-century organ, massive and elegant, adds an incomparable sonic and visual dimension. In the sacristies, the treasure of the Antonins still glitters, a tangible testament to the opulence and power of the order in its time. |

|

|

| From the church forecourt, a sweeping view opens up over the old village and the Furand river, which meanders at its feet. This perspective recalls the strategic and spiritual importance of the abbey, dominating the surrounding landscape like a stone lighthouse. |

|

|

| The village itself is a medieval gem, where history seems embedded in every winding alley and every stone. Its old houses, some built between the 14th and 15th centuries, vary between simple rubble constructions and more elaborate half-timbered structures. Here, shops from another time sit alongside the market halls, witnesses of a medieval daily life that has withstood the test of centuries. |

|

|

|

|

| For visitors seeking a unique experience, two kilometers from the village is a unique retreat: the Fontfroide cabins. These treehouses, nestled in the heart of a chestnut forest, offer an extraordinary stay. Each cabin, firmly anchored in slender trunks, seems to float in a lush green setting. The service is as particular as it is refined. Meals, drinks, and even breakfast are delivered via a rope and pulley system, with a rustic elegance. Though the cabins are surprisingly stable, a strong wind can make their structure gently sway, giving guests the sensation of sailing on an imaginary ship. This experience, combining comfort and nature, offers a rare sense of escape and communion with the environment. To reach these cabins or the Via Adresca, signs will guide you through serene forest paths. The adventure, whether spiritual or bucolic, begins here, in this corner of Dauphiné, where history and nature meet in perfect harmony. |

|

|

Official accommodations on the Via Adresca

- Camping de Roybon, avril-septembre, Roybon; 04 76 36 23 67/06 86 64 55 47; Camping, caravans, dinner

- Abbaye des sœurs cisterciennes, Abbaye de Chambarand, La Trappe; 04 76 36 22 68; Accueil monastique, book

- L’Arche de St Antoine, Place de l’Abbaye, St Antoine-L’Abbaye; 04 76 36 45 97; Communauté, dinner, breakfast

- L’Antonin, 106 Rue Corsière, St Antoine-L’Abbaye; 06 87 59 40 77/ 04 76 36 41 53; Guestroom, dinner, breakfast

- Chez Camille, 411 Rue Commandant Garaud, St Antoine-L’Abbaye; 06 82 43 05 99; Hotel, dinner, breakfast

- Cabanes de Fontfroide, à 1 km du GR, St Antoine-L’Abbaye; 06 17 09 55 75; Cabins on the trees, dinner, breakfast

Pilgrim hospitality/Accueils jacquaires (see introduction)

- Roybon (1)

- St Antoine-L’Abbaye (1)

On the Via Adresca, accommodation options are almost always limited. You won’t be passing through the more touristy southern part of the Ardèche. Lodging is scarce, even for Airbnbs, and their addresses are not available. The list only includes accommodations directly along the route or within 1 km of it. The Amis de Compostelle guide, however, lists all available lodging addresses, along with information on bars, restaurants, and bakeries along the route, and even several kilometers away. For meals, you can stop in Roybon. At the end of the stage, there are now more options for both food and accommodation in Saint-Antoine-l’Abbaye. From here, it’s also possible to walk another kilometer to spend the night at the « châtaigniers » (chestnut trees), where additional accommodation is available.

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 10: From St Antoine-L’Abbaye to Mours St-Eusèbe |

|

|

Back to menu |