Between the dreary Bièvre plain and the cheerful Chambaran hills

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

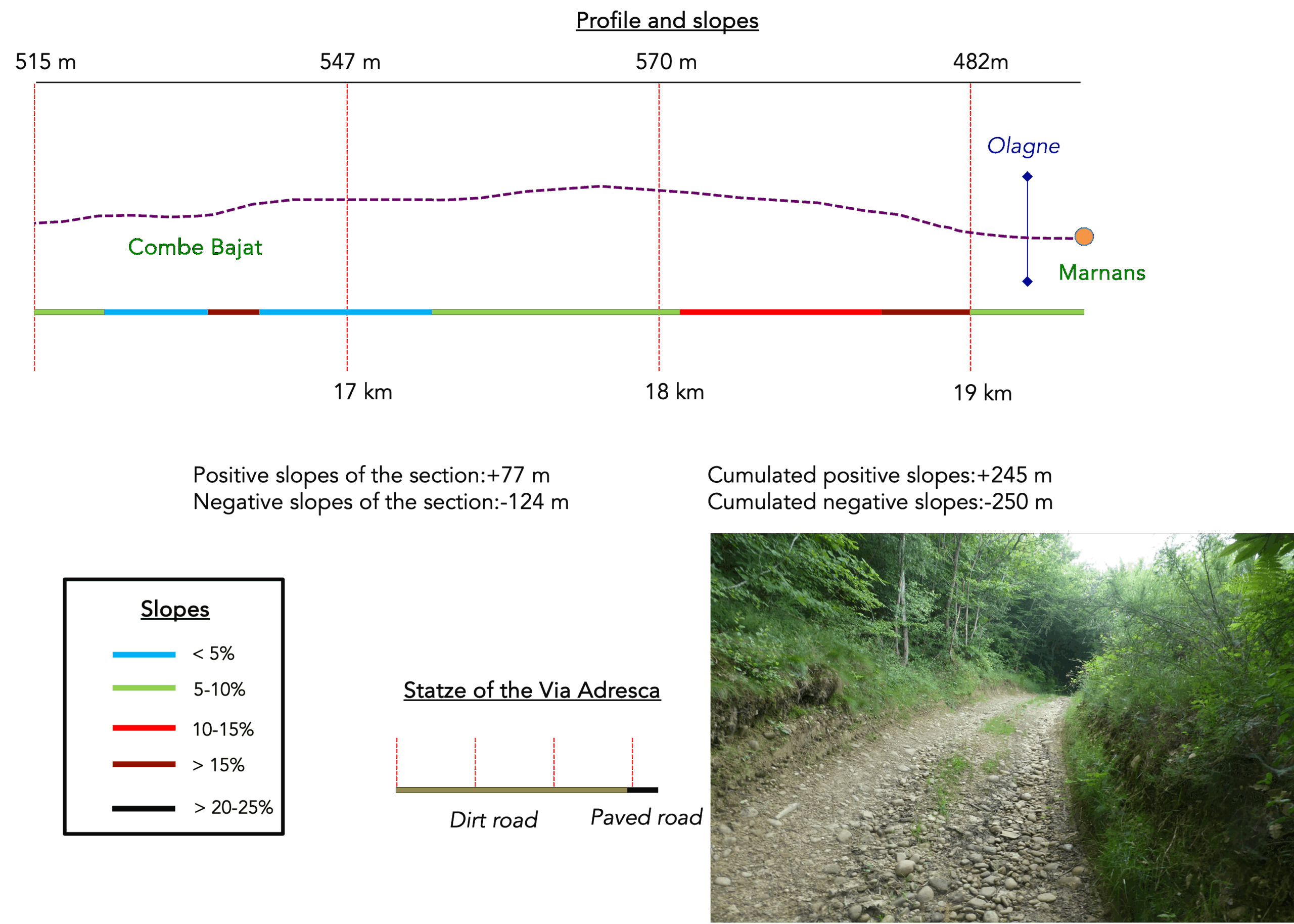

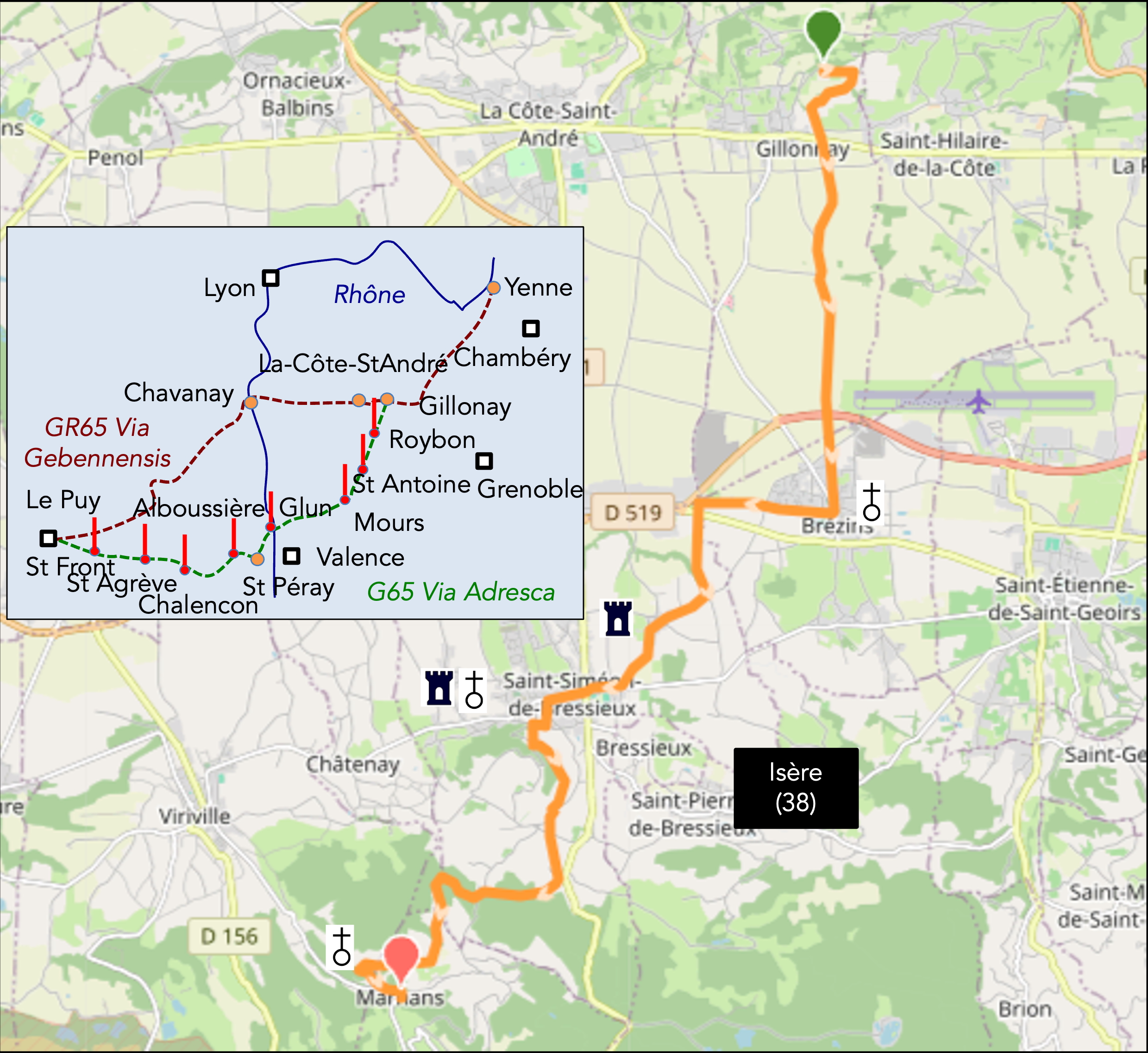

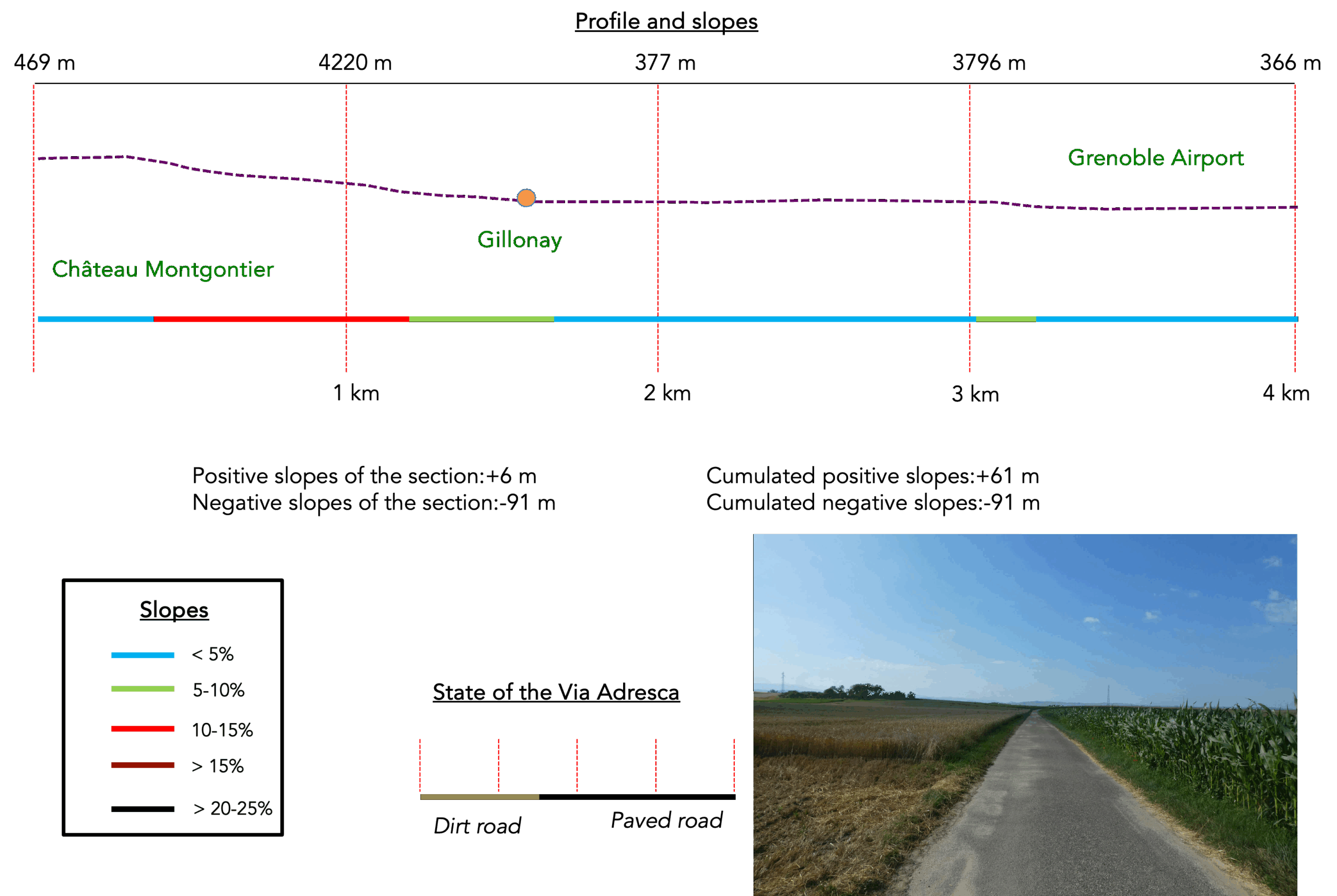

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-la-cote-st-andre-a-marnans-sur-la-via-gebennensis-adresca-32799398

| Not every pilgrim feels comfortable using GPS devices or navigating on a phone, especially since many sections still lack reliable internet. To make your journey easier, a book dedicated to the Via Gebennensis through Haute-Loire is available on Amazon. More than just a practical guide, it leads you step by step, kilometre after kilometre, giving you everything you need for smooth planning with no unpleasant surprises. Beyond its useful tips, it also conveys the route’s enchanting atmosphere, capturing the landscape’s beauty, the majesty of the trees and the spiritual essence of the trek. Only the pictures are missing; everything else is there to transport you.

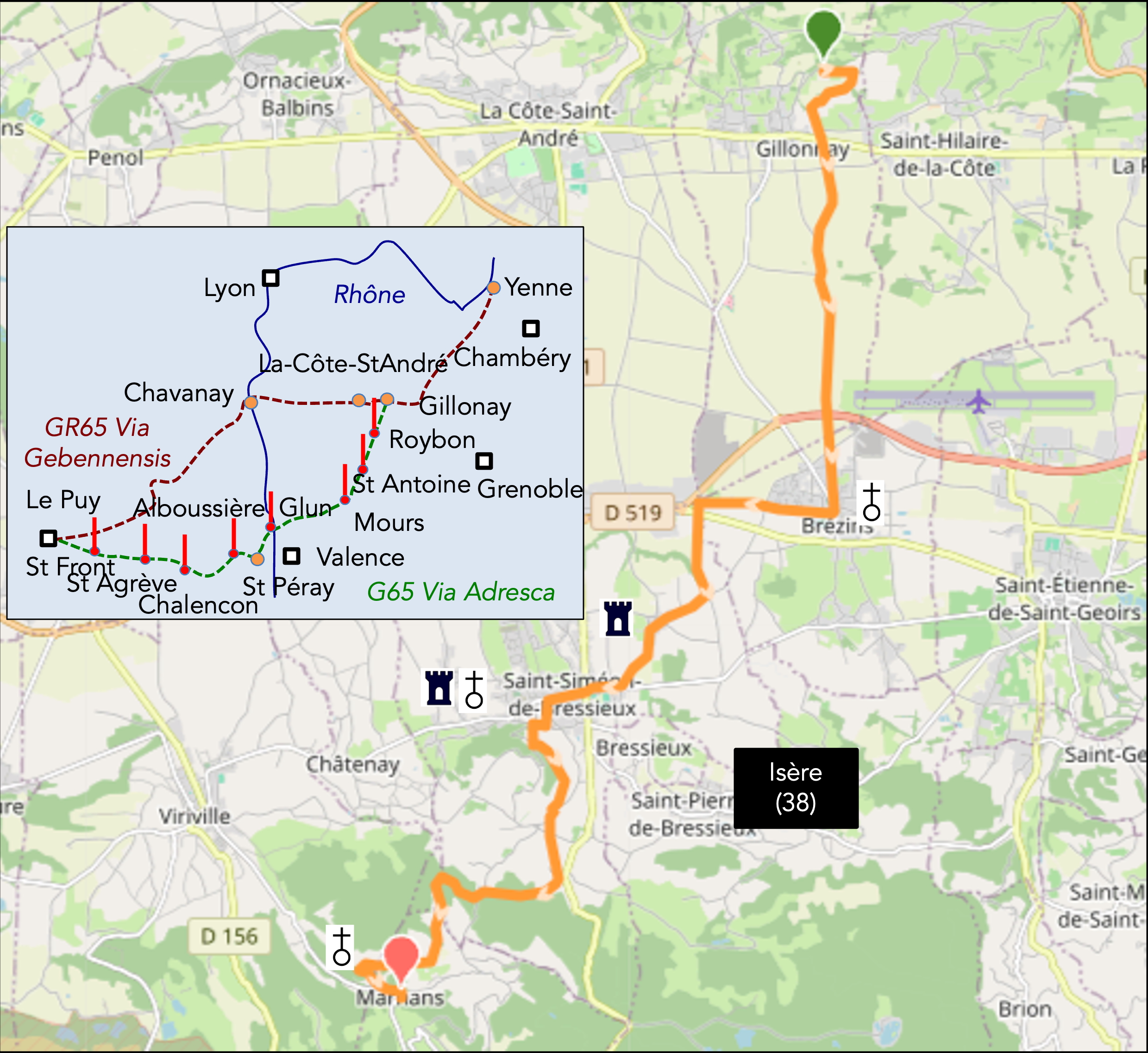

We’ve also published a second book that, with slightly fewer details but all the essential information, outlines two possible routes from Geneva to Le Puy-en-Velay. You can choose either the Via Gebennensis, which crosses Haute-Loire, or the Gillonnay variant (Via Adresca), which branches off at La Côte-Saint-André to follow a route through Ardèche. The choice of the route is yours. |

|

|

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

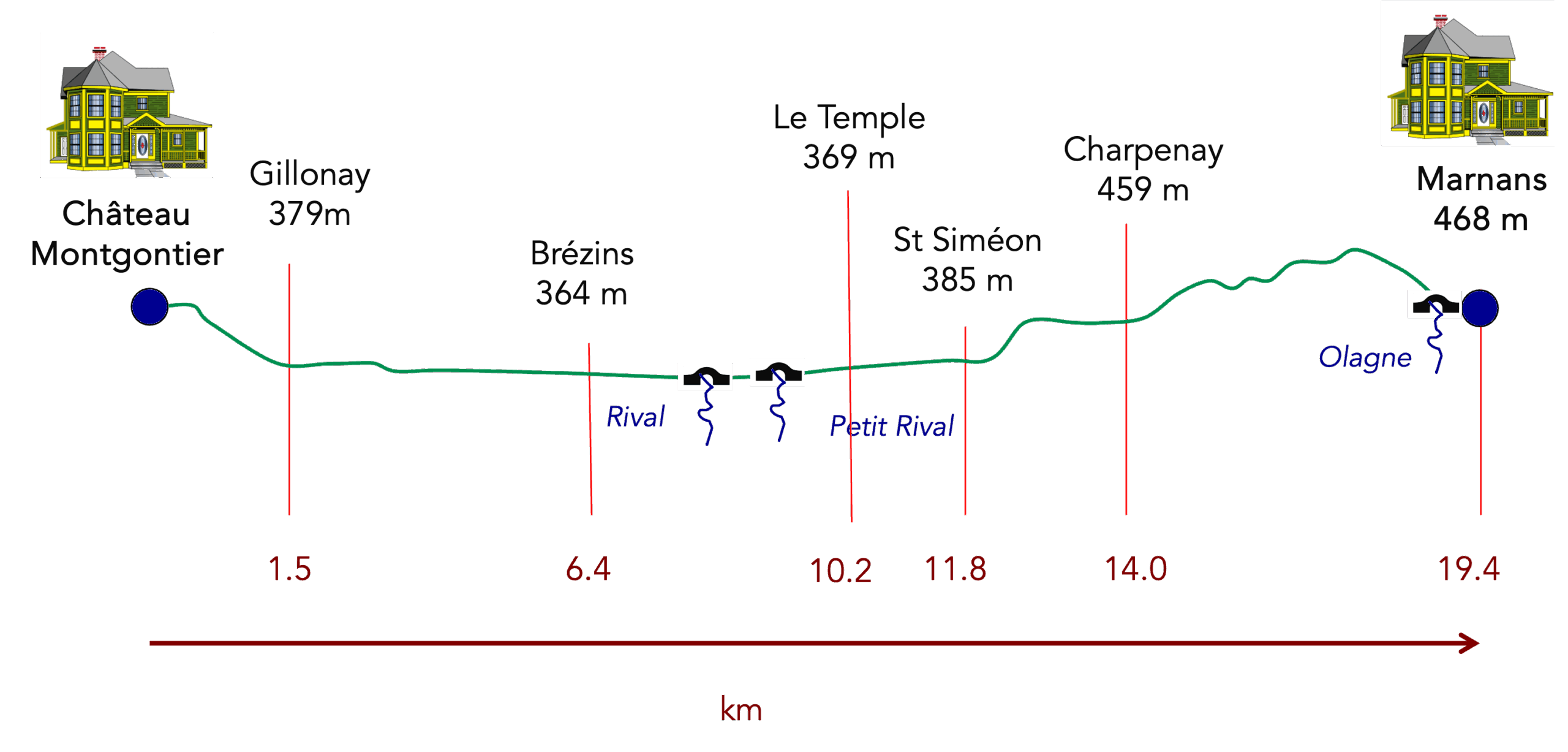

Today brings a change of direction, of light, and perhaps even of mood. The route leads you along the variant route of Gillonay, into the vast Bièvre-Valloire plain, an infinite expanse that seems to suspend time itself. This plain, your steady companion over the past few days, unfolds like a wide-open book. Further ahead, the first contours of the Chambaran come into view, a region with a bolder silhouette that towers over the Isère plain. In the distance, Valence emerges on the horizon, a silent sentinel at the end of the valley.

If you’re arriving from Grand-Lemps, the Château de Montgontier, austere yet welcoming, offers shelter for pilgrims. Be warned, though: hospitality here requires planning, and a reservation at least 24 hours in advance is mandatory. For those who’ve taken the route to La Côte-Saint-André, a short backtrack is necessary. But isn’t it a pilgrim’s privilege to embrace the detours imposed by the unpredictable nature of the journey?

Two possibilities guide you toward Le Puy-en-Velay: the Via Gebennensis and the Via Adresca. While the former is more popular, it’s not necessarily because of its beauty. The Via Gebennensis enjoys better coverage in guides, whereas the Via Adresca is reserved for a handful of insiders who seek more secluded paths. Yet, the latter does not lack charm. It invites immersion into the rolling Ardèche hills, their undulations shaped by ancient lava and still whispering the echoes of dormant volcanoes. While the Via Gebennensis stretches out toward the Rhône River before climbing into the Haute-Loire hills, the Via Adresca takes a more direct route, swiftly scaling the Ardèche heights. It reveals the landscape with rugged simplicity before delivering you to the doorstep of Le Puy-en-Velay. Two roads, two characters: one embraces, the other challenges.

As you traverse the Bièvre-Valloire plain, you uncover the secrets of a landscape that’s more than just an empty space. It’s a glacial trough, a remnant of the age when glaciers shaped the earth. Around it, moraines rise into gentle hills, strewn with pebbles polished by millennia. To the north, the Bonnevaux Forest, dense and dark, conceals bright clearings like pauses in a story. To the south, the Chambaran plateaus rise. These two forests frame the plain like parentheses, an echo of the titanic forces that once shaped this land. Today, the route or course leads you toward Chambaran, into terrain where reliefs disrupt the Bièvre’s serene flatness. The forest, dense and unpredictable, surrounds you. The crunch of your steps on fallen leaves is punctuated by the quiet songs of birds, as shadow and light playfully intermingle.

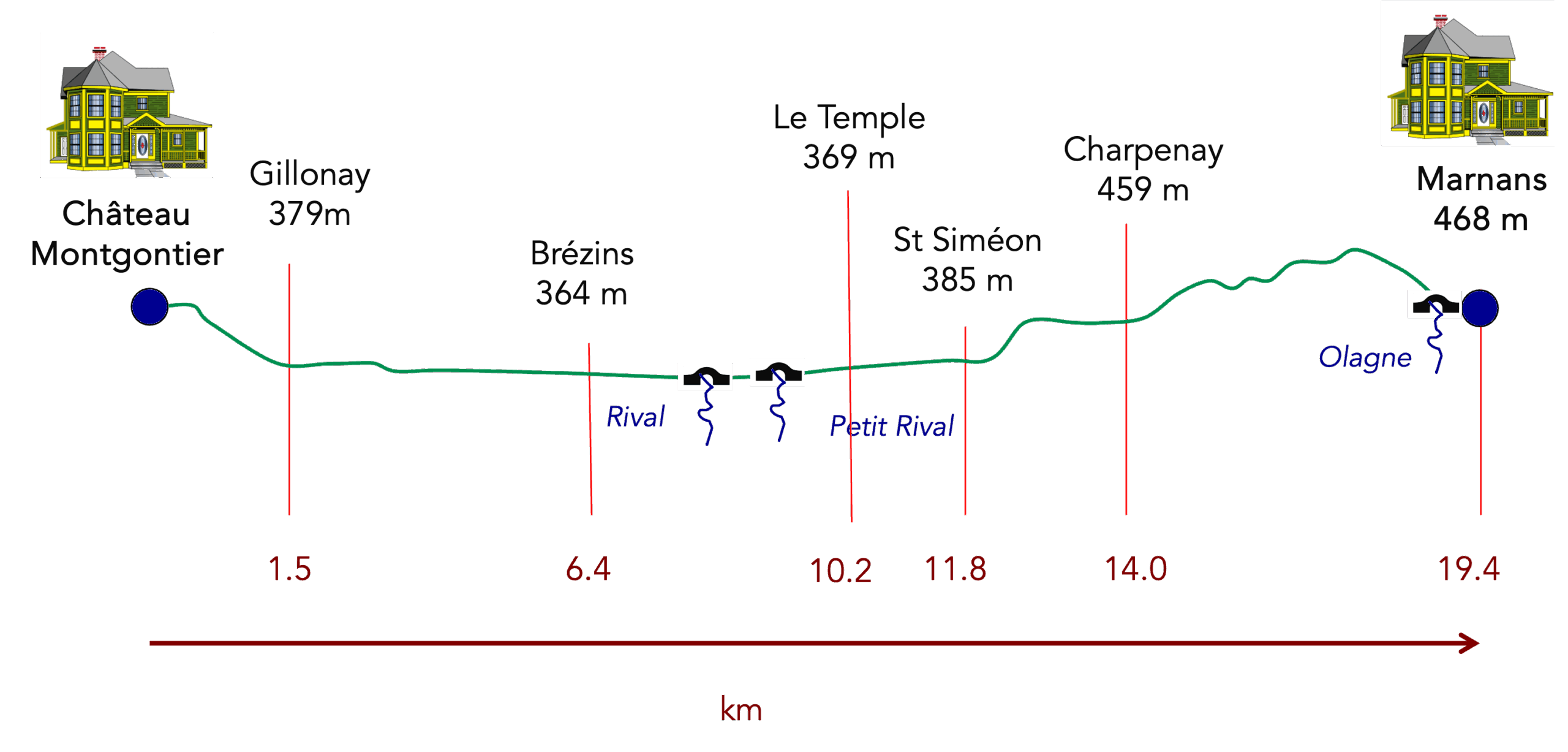

Difficulty level: Today’s stage presents no major challenges in terms of elevation: the climbs, though present, are gentle. The cumulative +387 meters and -293 meters are spread across routes that oscillate between ease and ruggedness. The Bièvre crossing, while serene and beautiful, can feel like a long, drawn-out sigh. Byond St Siméon-de-Bressieux, the terrain becomes a little livelier, with slopes that grow slightly steeper. However, even the steepest inclines rarely exceed 15%, whether climbing or descending. Here, the challenge lies less in physical exertion than in the nature of the terrain: paths are often littered with stones. Every step must be deliberate, every rock either skirted or carefully tackled.

State of the Via Adresca: For today’s stage, you’ll spend more time on paved roads than paths:

- Paved roads: 14.0 km

- Dirt roads : 9.7 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

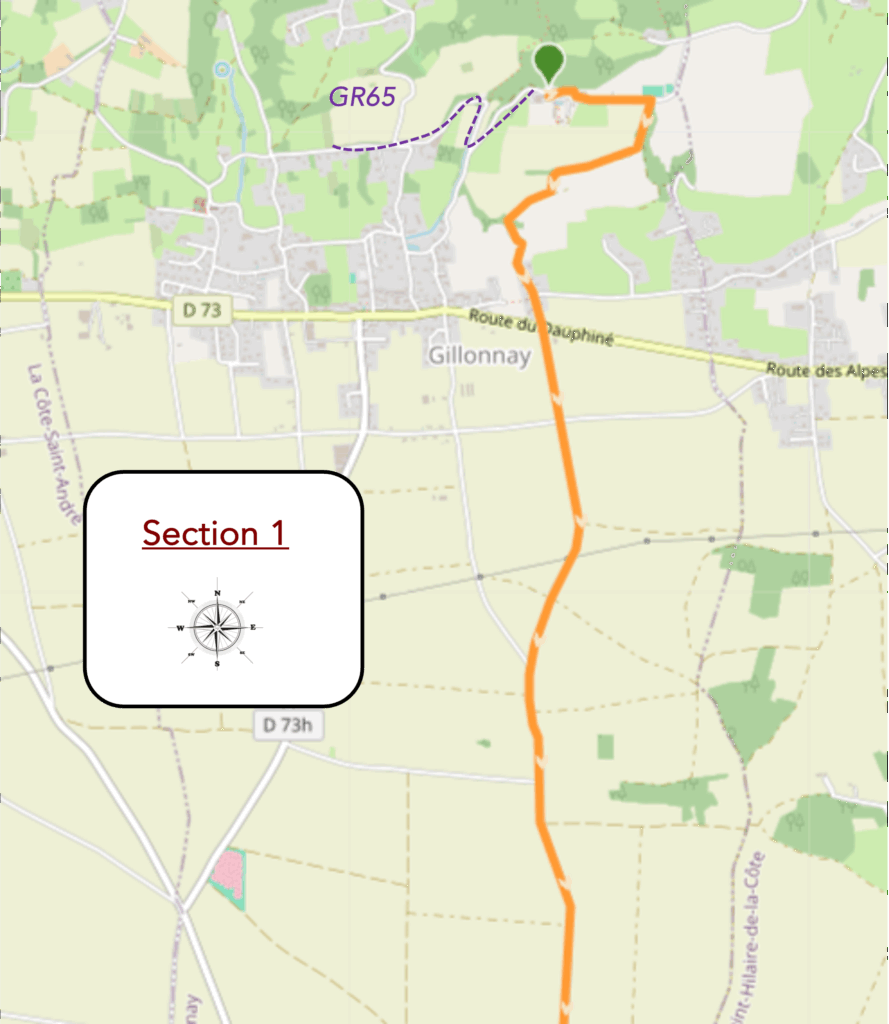

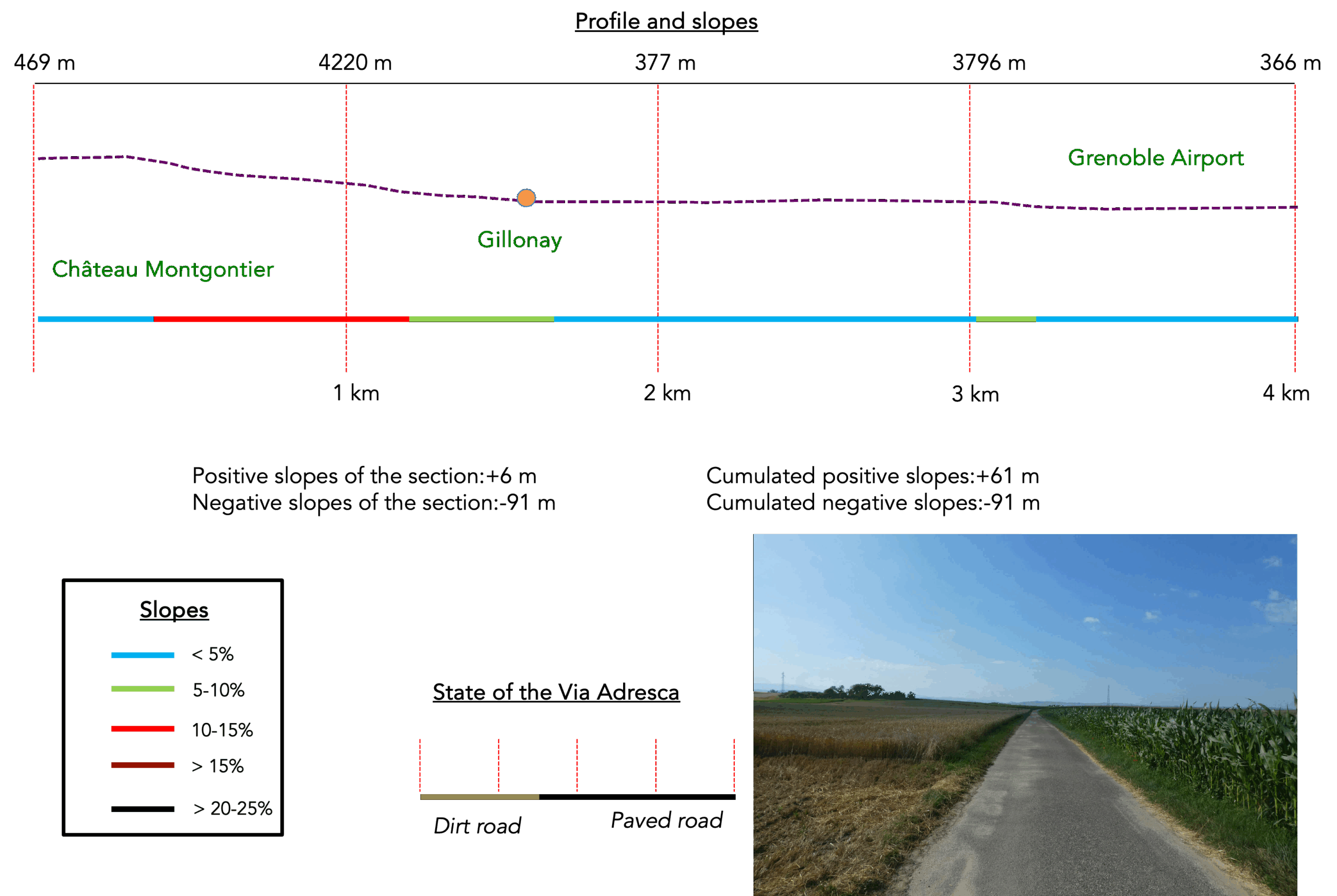

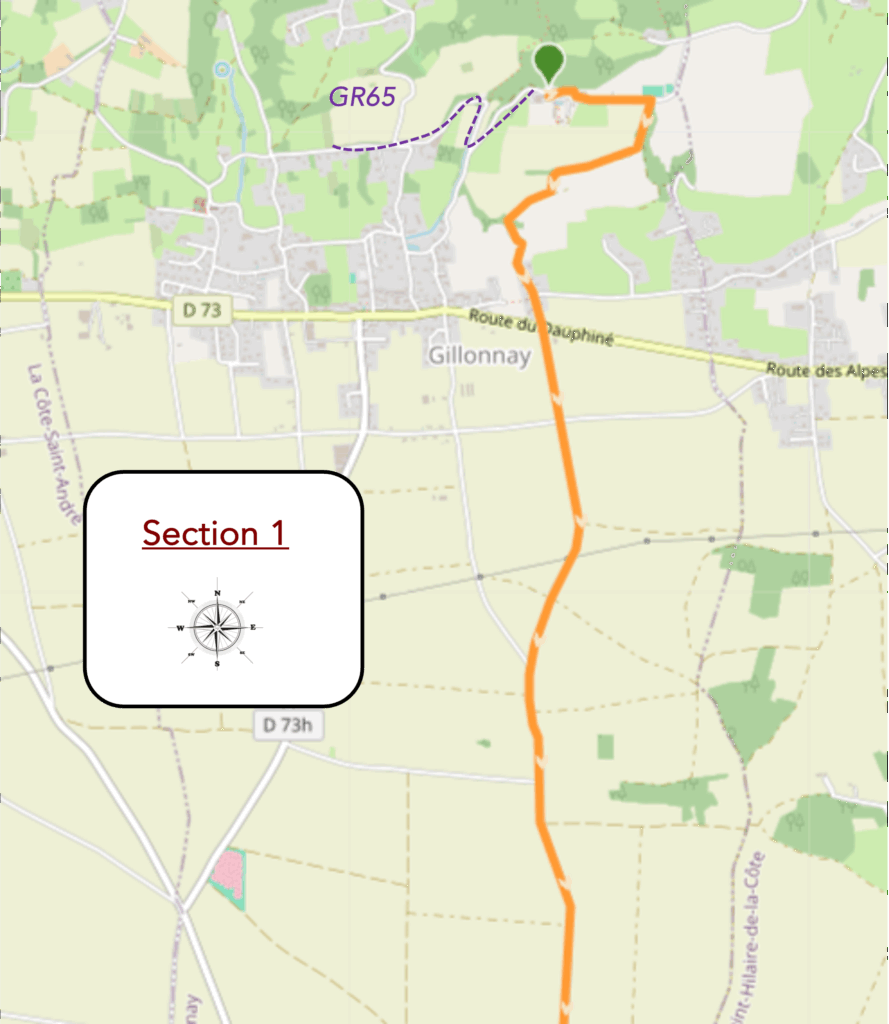

Section 1: On the bleak plain of Bièvre-Valloire

Overview of the route’s challenges: Beyond the downhill slope to Gillonay, it’s flat.

Both routes lead to Le Puy-en-Velay, but the Via Gebennensis has clearly taken precedence over the Via Adresca. You will encounter few pilgrims on the Via Adresca, a route more often used by lovers of the Ardèche region. However, rest assured, this path is just as worthwhile as the other. Since there is often confusion between the GR hiking trails and the Way of S. James, we will use the term « Via Adresca » to refer to this route.

Montgoutier Castle marks the true starting point of the Gillonay variant, also known as the Via Adresca. This historic site, with its imposing silhouette, is an invitation to travel in itself, an open door to a path steeped in mystery and adventure. Here begins the course, where each step takes the pilgrim further into the discovery of oneself and the world.

| The junction is impossible to miss, clearly and precisely signposted with a series of signs. The directions, clear and visible, form a reassuring trail for walkers, as if the path itself whispered encouragements not to stray. |

|

|

| On this section of the Via Adresca, the path gently slopes down, bordered by large pebbles forming a rough stone path, scattered beneath a thick canopy of leaves. With each step, the crunch of stones beneath the feet echoes in the silence of the underbrush, reminding that this path is ancient, trodden by generations. It is worth highlighting the admirable work of the Rhône-Alpes Association of Friends of Saint-Jacques, which has meticulously marked the course to ensure the safety and orientation of pilgrims. However, from the very start, caution is needed. There, on a large oak tree, a discreet shell marks a turn to the right. |

|

|

| But if the walker passes through at a time when tall grasses and dense leaves hide the path, the shell may go unnoticed, buried beneath the foliage. Without this marker, it’s easy to go astray and continue straight along the stream. This deceptive path, appearing welcoming, actually leads to a dead-end, where barbed wire and barricaded gates of farmers abruptly block the pilgrim’s momentum. A frustrating detour that discourages the most daring. However, let us not blame this inconvenience on the Friends of the Association; they cannot transform into perpetual gardeners, always ready to trim the foliage that sometimes hides the trail markers. |

|

|

| The path, shaded by tall leafy trees, is carpeted with rolling stones underfoot, adding a peculiar rhythm to the walk. These stones, polished by the passage of pilgrims and time, too, tell the silent story of the path. |

|

|

| The crossing of the underbrush is brief, and soon, the pilgrim emerges from the shadow to find the light and open meadows. There, under a sky of brilliant blue, the view opens up to a vast expanse of fields that must be crossed without hesitation. To the right, a hedge of underbrush leads the walker gently toward the vastness of the Bièvre Plain stretching out before them, an endless horizon and the promise of a new chapter. |

|

|

| The path winds through shaded undergrowth and austere cornfields, in a countryside where harmony seems absent. The air is not filled with plenitude, but rather a discreet heaviness, like nature on standby. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the path reaches the outskirts of Gillonay, a village dotted with ochre adobe houses, their warm and soft hues embodying the particular charm of the Dauphiné. Some of these buildings are simple barns, with rough walls worn by time, while others still serve as shelters for inhabitants, witnesses of the rustic and peaceful life of the place. |

|

|

| At this point, the journey becomes a crossing of the great Bièvre-Valloire Plain. This stretch, more than six kilometers wide, gives the walker a sense of infinite horizontal space. The road does not always follow a straight line, but instead traces gentle curves, like a long crank that seems to stretch time itself. Depending on the mood, this journey can be a melancholic pleasure or a tiresome ordeal, a feeling of slowness where the gaze is lost in the vastness. The land here is largely dominated by corn and rapeseed cultivation, with tractors tirelessly plowing this vast sea of vegetation. Occasionally, wheat or soybeans break the dominance of yellow and green, but the true star remains the vast monotony. Sunflowers, on the other hand, appear fewer than in other regions. |

|

|

| Then, the course heads to the D73 department road, which cuts across the Bièvre Plain and runs alongside the village of Gillonay, winding through the land like a silver thread suspended between the hills and the valley. |

|

|

| The electric pylons, imposing and modern, punctuate your progress like mechanical landmarks. But the true anchor for the eye is the Grenoble airport, slowly emerging on the horizon, a concrete and glass monolith rising in the light. Here, the landscape transforms into a sort of Spanish Meseta, a cultivated expanse where the soul seems to dissipate. The difference lies in the duration of this crossing: in Spain, the Meseta stretches for hundreds of kilometers; here, the feeling of confinement lasts only a few hours. |

|

|

| As you advance, the trees become scarcer, driven away by the large tractors whose wheels mercilessly uproot them. Nature today is dominated by crops and agricultural industry, and one almost regrets the shadows of the old woods that have disappeared. |

|

|

| It would, however, be wrong to believe that the plain is perfectly flat. Unexpectedly, a small bump appears, a gentle undulation, almost imperceptible, hiding an oasis of shade and coolness: cherry trees, which, by their presence, bring a touch of poetry to this otherwise bleak landscape. Under their branches, the air seems to cool, offering respite to the weary soul. The road then descends from what might naively be called a hill, resuming its slow course through the vast plain. |

|

|

| From a distance, you will see the buildings of the aerodrome becoming more and more distinct on the horizon, but it will still take you a long while to reach them. They are just one landmark among many, a distant mirage that only reinforces the distance yet to be traveled. |

|

|

| Behind the fields of rapeseed, soybeans, sunflowers, and corn, crossing this vast expanse feels endless, a stretch of space where the monotony is barely broken by the hills that slowly emerge in the distance. Gradually, the mountains of the Isère appear, closer with each step, growing in the sky like a promise of an end, of relief. |

|

|

| To say that this plain is cramped would be a misconception. The horizon here seems to stretch beyond the imaginable, infinitely vast, like a dream of endless space. |

|

|

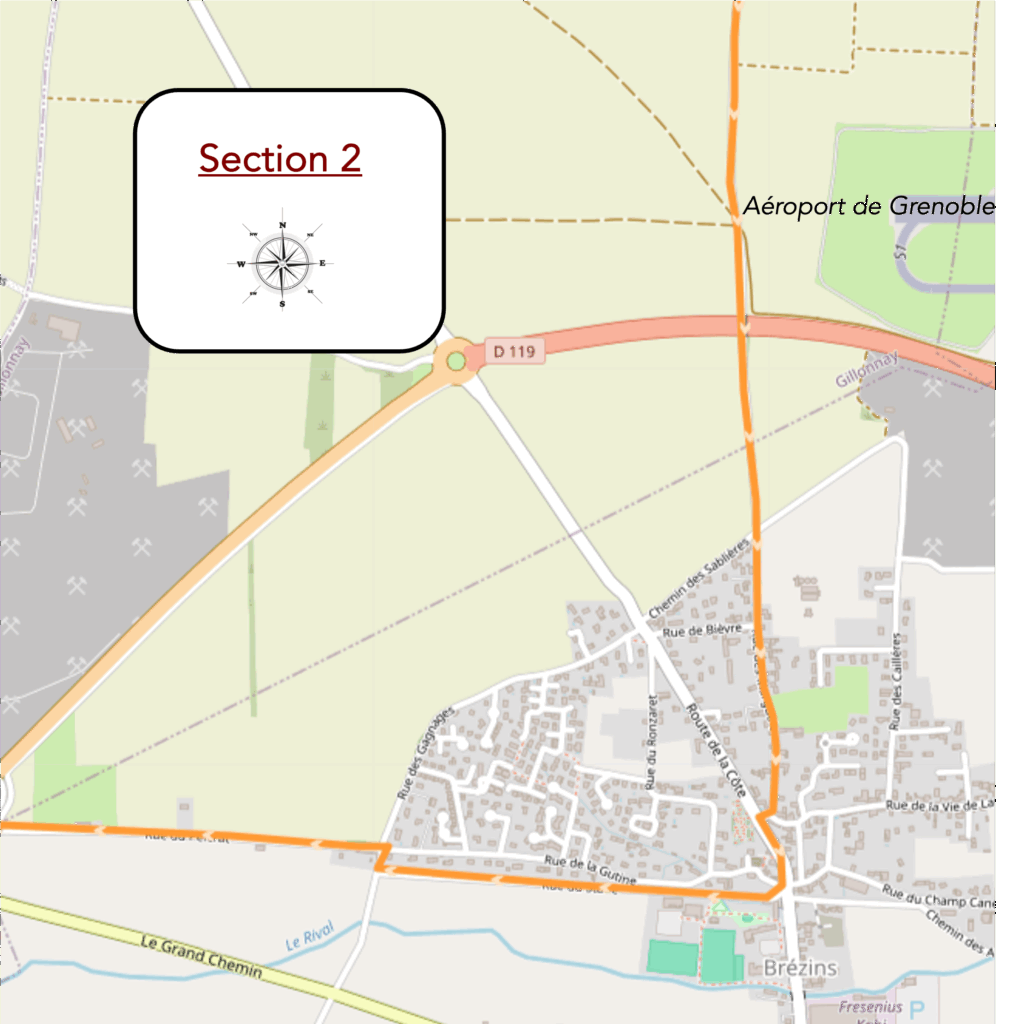

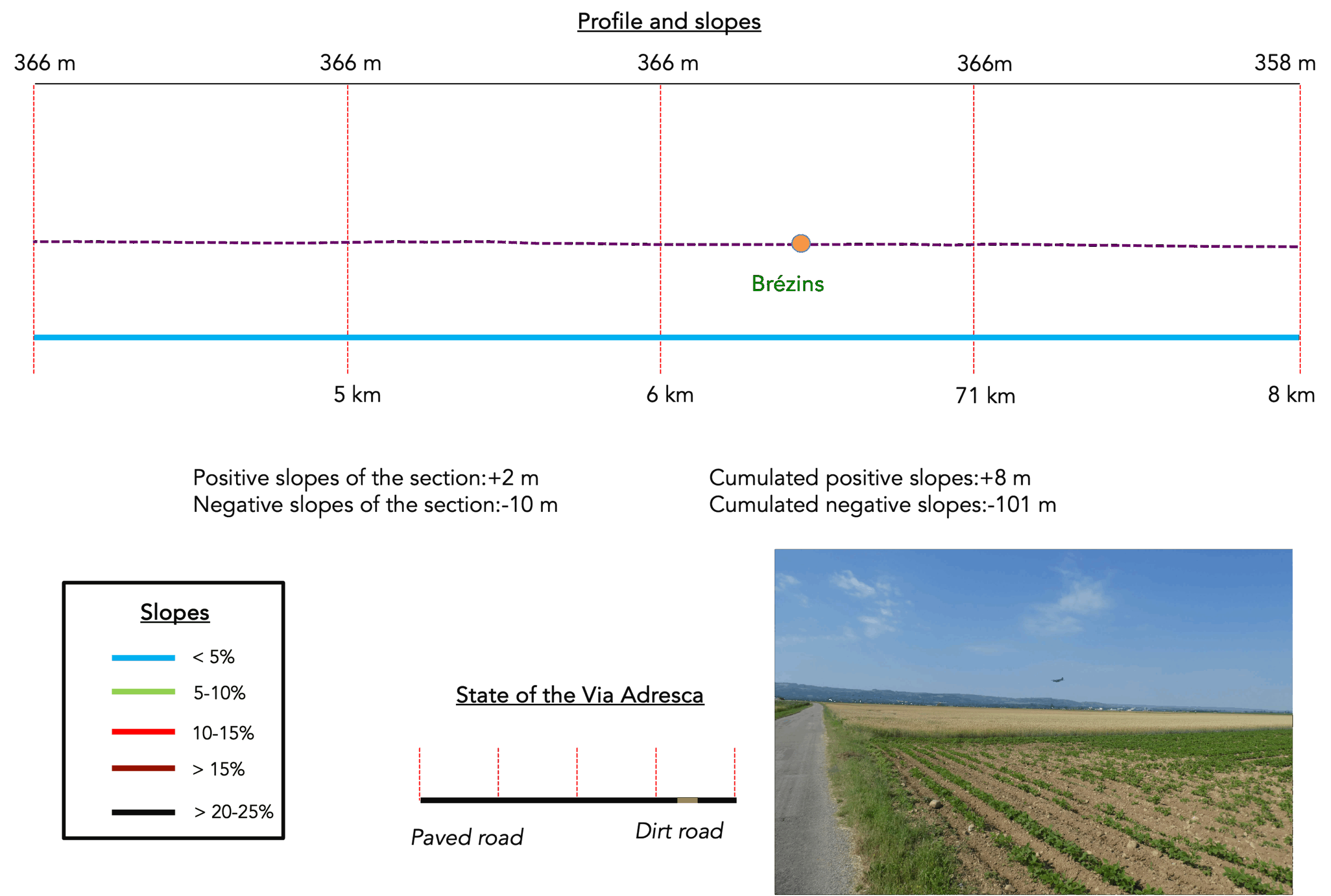

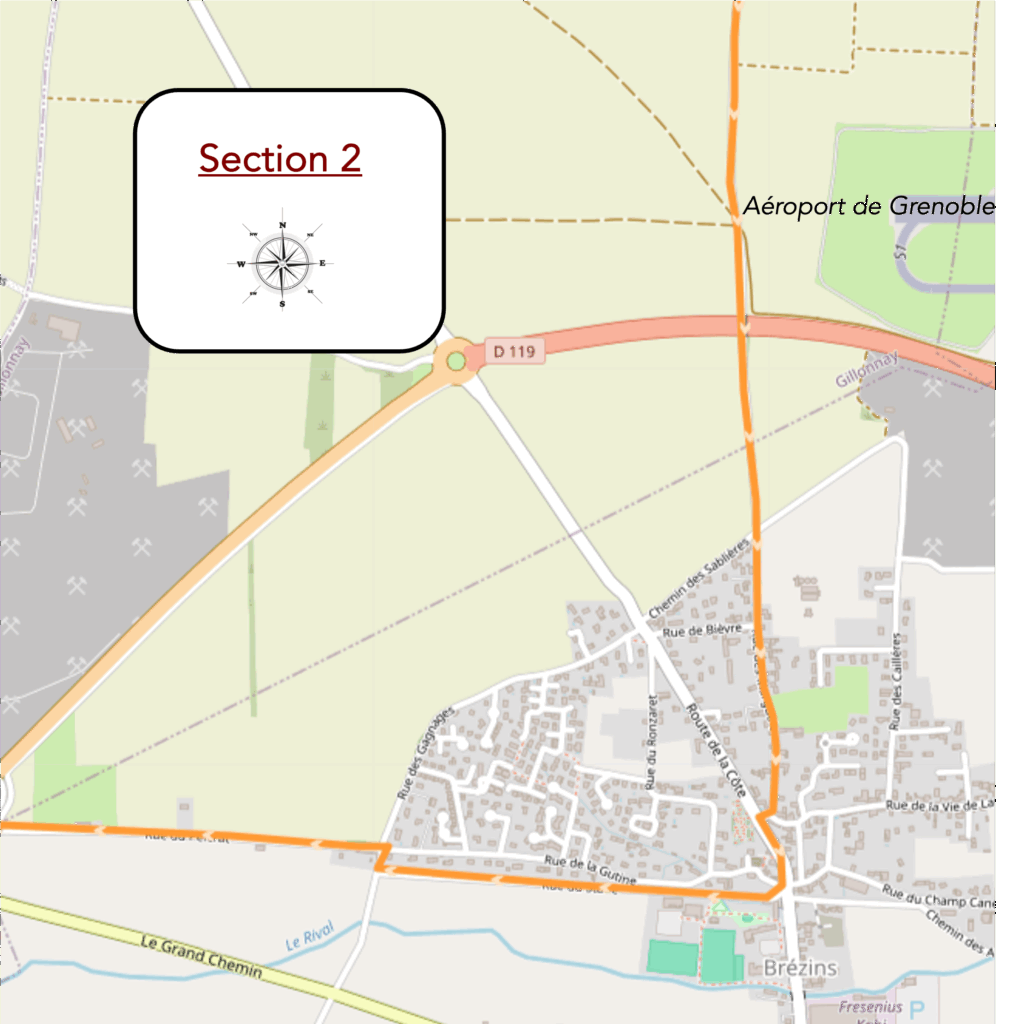

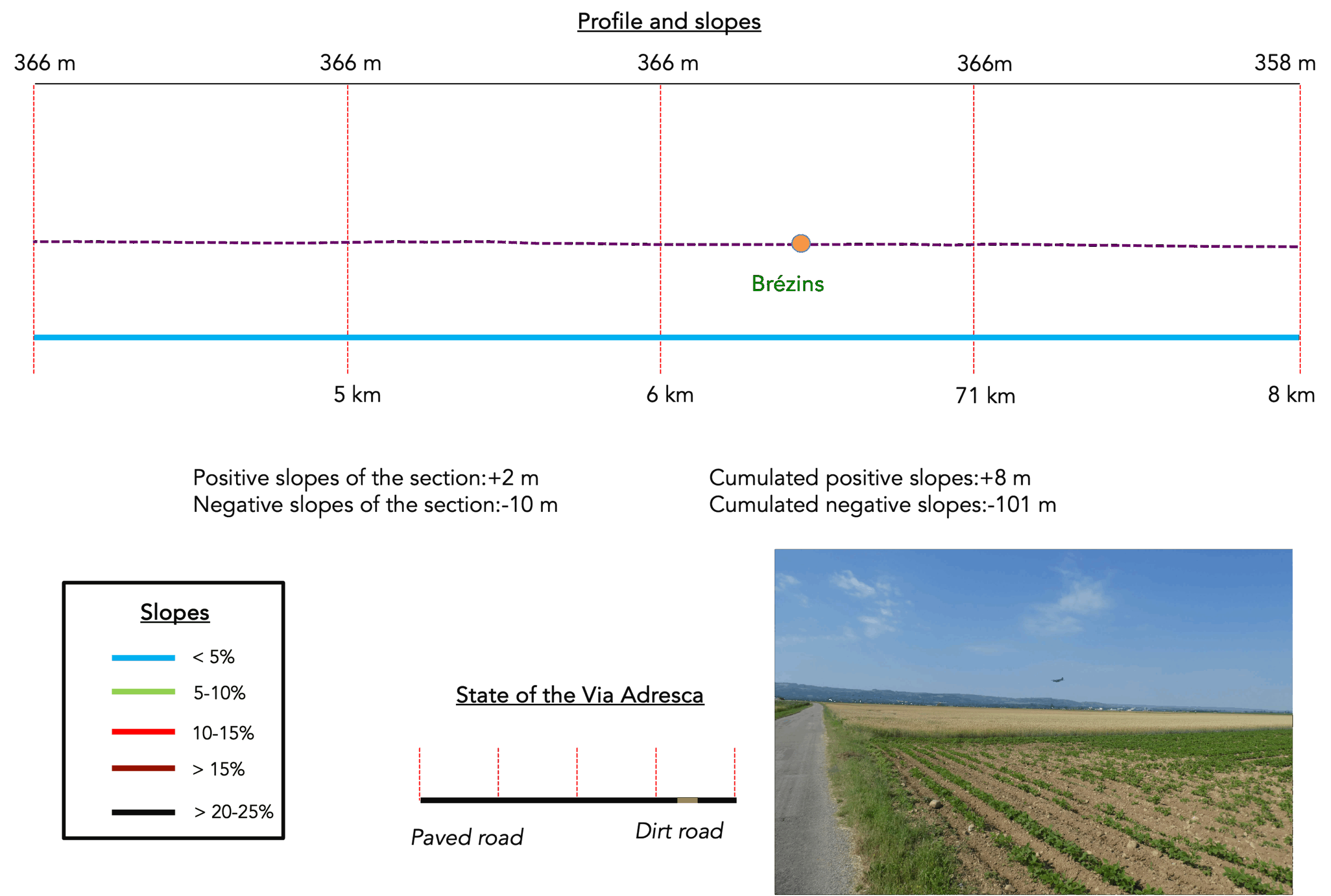

Section 2: Near Grenoble Airport

Overview of the route’s challenges: it is flat.

| Then, on this paved road that seems to stretch endlessly, your gaze suddenly catches an unexpected scene: small planes, like mechanical birds, begin their descent toward the airport. |

|

|

| The road sways, moves away, then disappears behind the unassuming silhouette of Grenoble-Isère Airport. Looking up, you see only a few modest aircraft, those familiar « little planes » of flying clubs. At first glance, nothing here suggests a major air hub; the place could pass for one of those sleepy provincial airports. Yet, in winter, a modest bustle takes hold of the area: low-cost airlines bring groups of skiers, eager to rush down Isère’s snowy slopes. With about 350,000 annual travelers, the airport ranks only 34th nationally, a modest performance compared to Grenoble’s population of over 170,000. For comparison, Geneva, a city of slightly more inhabitants, hosts 17 million passengers annually. The distance doesn’t help: from Grenoble’s center, fifty kilometers separate travelers from this airport. Such a gap? You might as well walk there, like you are! |

|

|

| In the immediate vicinity of the airport, the paved road sways again and flirts with the highway. This highway, the A48, connects Grenoble to Lyon, but here it is merely a discreet ramp leading to airport facilities. Seldom traveled, almost silent, it seems to wait for the rare vehicles daring to venture there. On this section, solitude reigns. |

|

|

| The A48 Highway connects Grenoble to Lyon. To the left, the factories of the Marguetière industrial district rise with their concrete and steel silhouettes, promising relentless labor. To the right, the landscape opens up: the eye sweeps across to the town of La Côte-Saint-André, perched on its hillside, as if serenely gazing at the vast plain of Bièvre. |

|

|

| The road then mischievously leads you to the village of Brézins, which at first glance appears to nestle against a protective hill. Its red-tiled roofs, lit by a hesitant sunbeam, give it a peaceful appearance. But the illusion is short-lived: the plain stretches as far as the eye can see, forcing you to continue your path, ever farther, across this land where time stretches like a slow melody. |

|

|

| Then comes the village, long and sprawling, marked by ancient architecture. The earthen buildings, witnesses to ancestral craftsmanship, lend the place an almost poignant humility. Here, everything breathes modesty: neither grandeur nor brilliance disrupts this simplicity. This village, without artifice, seems to whisper tales of the past. |

|

|

| In a discreet corner, a resident has displayed a thought-provoking message. Three words stand out: truth, good, utility. These are Socrates’ three principles, the legendary test encouraging people to share only words that are truthful, kind, and necessary. In this rural setting, this call to ancient wisdom takes on unexpected depth, echoing a forgotten humanism. |

|

|

| Finally, the church reveals itself, humble and tucked away, behind tall earthen walls seemingly designed to protect it from the outside world. It stands there, a testament to a discreet yet valuable heritage, emblematic of this Dauphinois land in Isère. Its simplicity speaks volumes about the history of this place: rooted in tradition, a memory whispered through its stones. |

|

|

| As the Via Adresca finally leaves the village, a vast expanse unfolds before you: a flat, endless horizon reminding you that St Siméon-de-Bressieux, the next turning point in the course, is still over five kilometers away. Here, the Bièvre plain stretches uncompromisingly, demanding patience, with only the promise of distant hills to sustain you. These gentle, soothing hills wait as a deferred reward, beyond this monotonous stretch. Be patient, for the route offers no mercy! |

|

|

| At the exit of a village that seems to stretch indefinitely, traces of the past emerge. There, the rusty remnants of an abandoned railway can be glimpsed, silent witnesses to an ambitious project of yesteryears: connecting these lands to the industrial zone, two kilometers away. But these local ambitions are now swept away by a national wave: soon, only TGV lines linking major metropolises, Paris, Marseille, Lyon, Strasbourg, Bordeaux, will remain in France. The echo of this vanishing railway world adds a subtle melancholy to this landscape, already marked by weariness. |

|

|

| Near a recently developed area, where a few functional buildings form a sort of service district, a gravel path runs straight ahead. It cuts through the plain with an almost austere simplicity, bordered by fields where meadows, wheat, and hedges of deciduous trees alternate. A rustic geometry, devoid of ornamentation, where nature arranges itself without flourish. |

|

|

| To love this plain, one perhaps must be born here, or find a reason granted only by an intimate attachment. For those crossing it, it inspires a heavy solitude. In the distance, the silhouette of the Marguetière industrial zone breaks the landscape’s uniformity but offers little comfort. It is a functional place, seemingly devoid of soul, where production occurs without lingering. |

|

|

| The Stadium Alley soon emerges, somewhat unexpectedly, into a more inhabited meander. Where the gravel yields to asphalt, a small fork leads to an area where the buildings seem familiar again. |

|

|

| Here, the earthen constructions and pebble walls, typical of the Dauphiné, strongly recall the tradition and identity of this region, already encountered along the traditional Via Gebennensis. They are marks of a discreet resistance, a heritage refusing to fade. |

|

|

| On this plain segment, agriculture dominates. Oilseeds, soybeans, and especially rapeseed reign over these lands. They drape the fields in a seasonal cloak, sometimes vibrant yellow, but the absence of cows and meadows lends this landscape an almost disconcerting singularity. Here, farming has adapted to modern demands, leaving behind the bucolic image of yesteryear’s countryside. |

|

|

| The paved road, true to itself, continues its unending journey, skirting fields with relentless determination. Slowly, it approaches the Marguetière, as though its destiny inexorably leads to this industrial enclave, where the plain finally hints at a new chapter in the landscape’s story. |

|

|

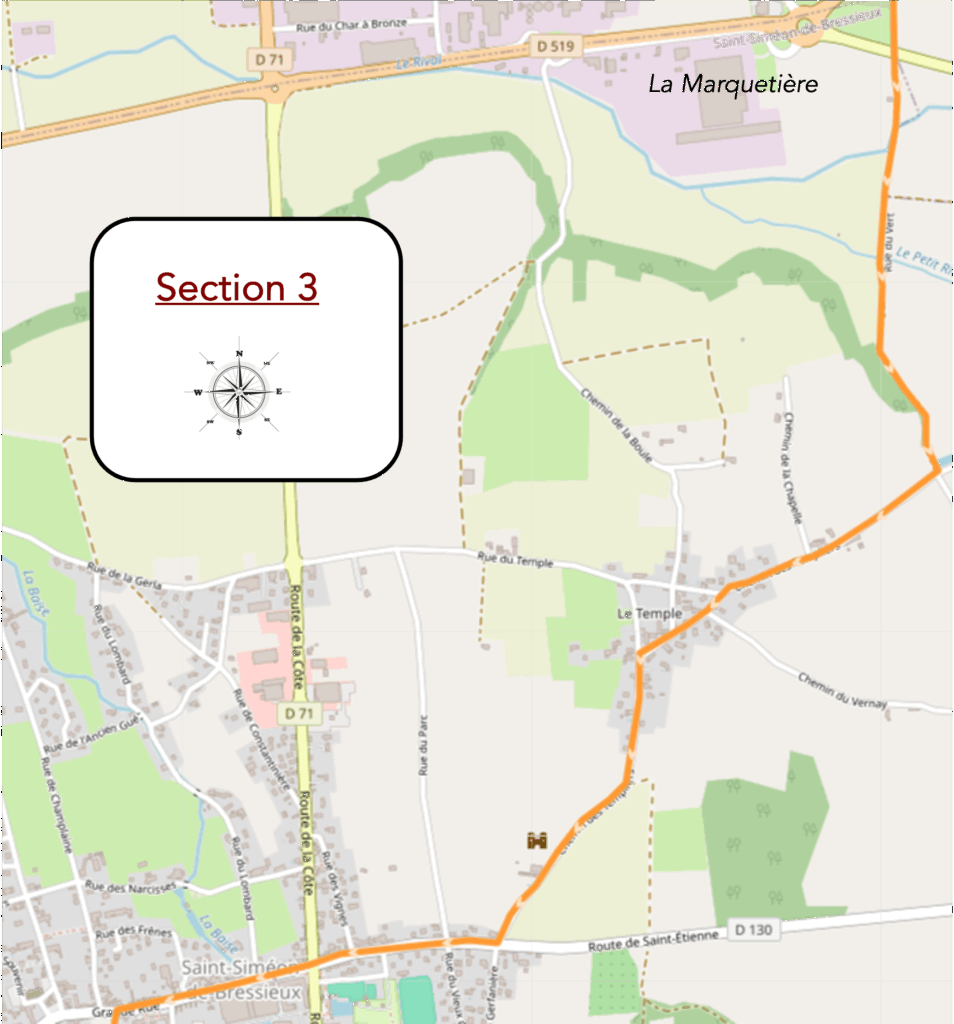

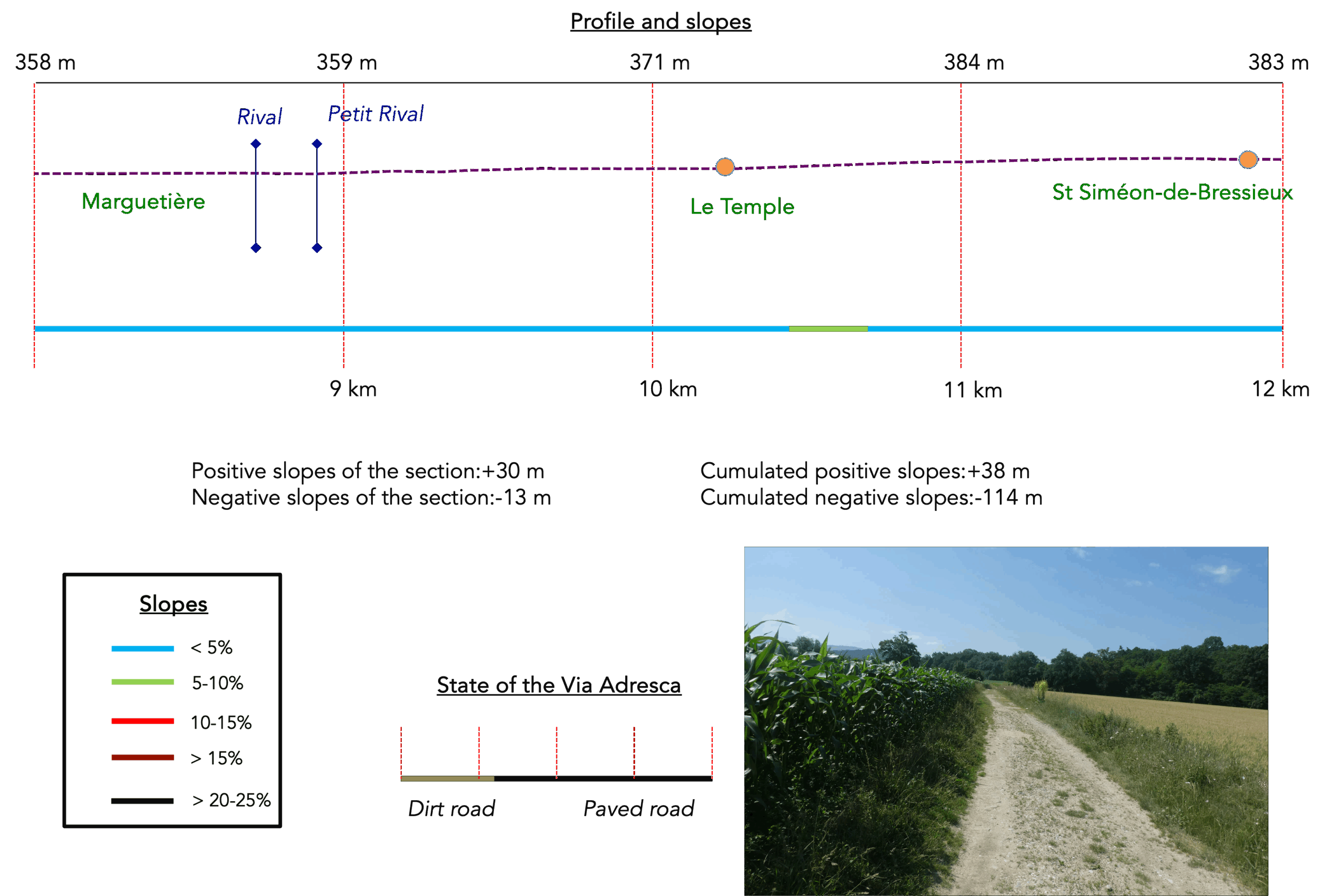

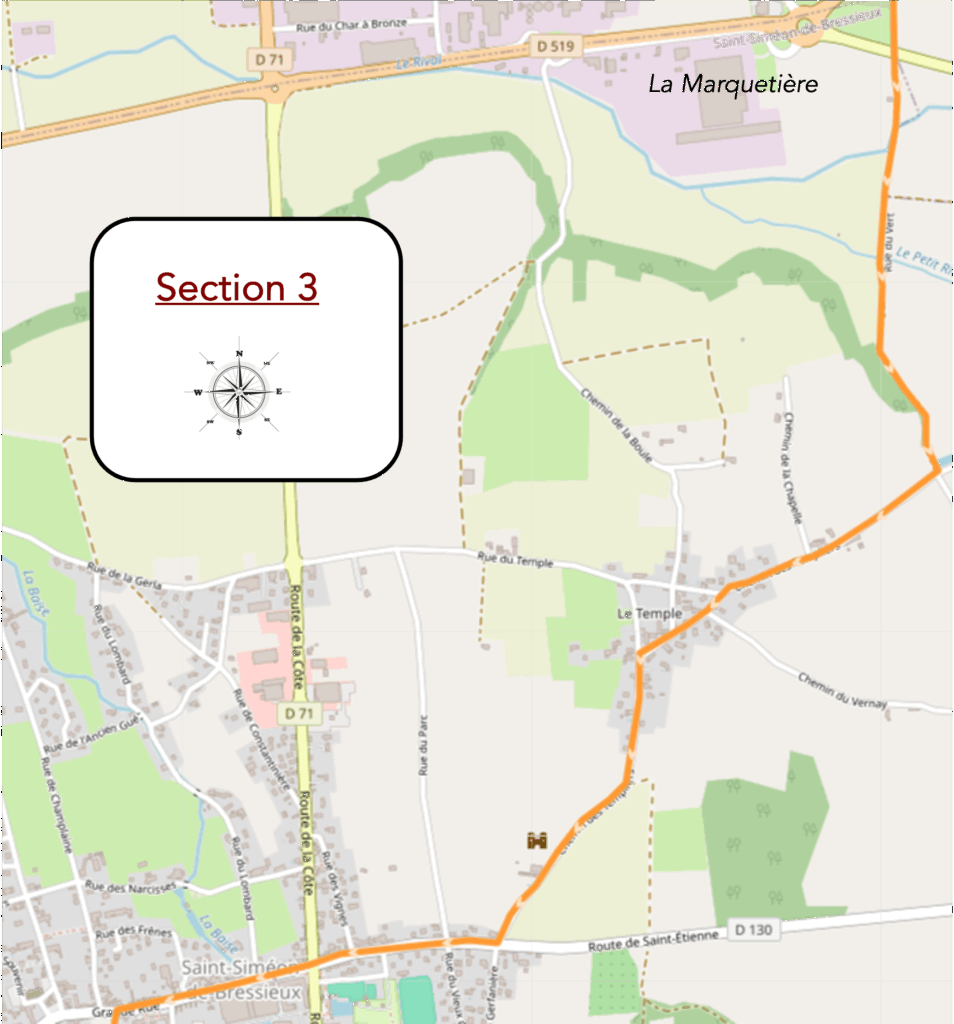

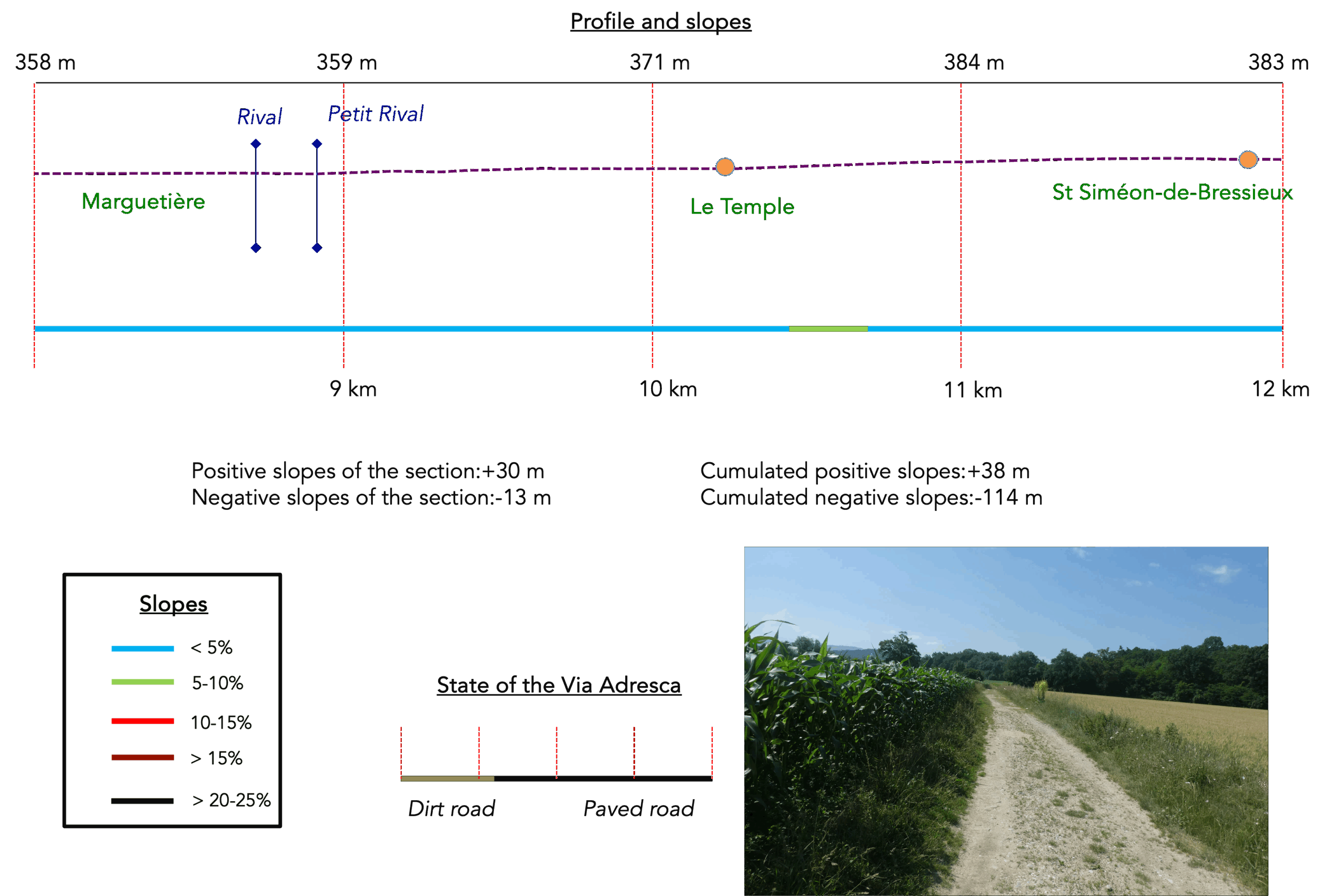

Section 3: To the edge of the Bièvre-Valloire plain

Overview of the route’s challenges: It is flat, or almost so.

| The paved road stretches slowly to the industrial area of La Marguetière, a territory you have long seen on the horizon during your languid crossing of the plain. This place, with its modest and pragmatic appearance, betrays its utilitarian function: it houses massive industries, one of which produces concrete, and it seems to engage in a prosaic dialogue with the highway that flanks it. Beyond the vivid yellow expanse of rapeseed fields, the hills of La Côte-Saint-André timidly sketch their silhouette, like a distant promise of more welcoming horizons. |

|

|

| Skirting the industrial zone becomes a kind of obligatory passage, a lackluster detour where the highway draws its ramp like a line indifferent to the surrounding landscape. Here, everything seems so monotonous, so languid, that the absurd idea of wandering on the highway itself might almost cross the mind of a spirit seeking novelty. The inertia of this place imposes itself as a weight, where the horizon seems to hesitate between abandonment and boredom. |

|

|

| At the exit of this territory of iron and concrete, a crossroads marks a slight revival of movement, like a pause on the asphalt where the paths scatter toward other promises. You are then a little over three kilometers from St Siméon-de-Bressieux, an anchor point that finally seems to announce something more human, more approachable. |

|

|

| Then, the landscape suddenly gives way to unexpected softness: a dirt path moves away from the straight roads and the noise of engines, venturing into a sea of wheat and corn. It crosses the Rival stream, a clear and carefree watercourse that restores a simple and bucolic charm to the landscape. Here, the plain breathes a little better, becoming brighter, almost cheerful in its blend of crops and small streams. Pilgrims and hikers will find a welcome respite here, a breath of serenity in a landscape that softens. |

|

|

| A little further, the path seems to enjoy following the Petit Rival stream. The water becomes a guiding thread, almost a motif in this pastoral tableau, while an old peasant saying whispers in your ear: a little water is always needed to appease the insatiable thirst of the corn. This refrain accompanies the scenery, adding a familiar and rustic touch. |

|

|

| However, not everything is sweetness and harmony. The fields, despite visible efforts by farmers to rid their meadows of stones, do not always offer striking beauty. The corn, often dull, imposes itself gracelessly in these lands that sometimes lack poetry. The path itself becomes stony, almost recalcitrant, running along a wooded area where the shade of the trees seems to hide a hint of fatigue. |

|

|

| Finally, the dirt path opens onto a paved road leading to the village of Le Temple. Once again, water becomes a companion to the traveler, meandering in a thin stream under the benevolent protection of oaks, hornbeams, and ashes. Here, no pilgrim will complain about leaving the rough pebbles of the path to briefly take the asphalt, as if offering a truce between two segments. The road, bordered by nature and water, finally soothes tired feet and reflective mindss. |

|

|

| The paved road, gently sloping up, leads to the scattered houses of the village, remnants of a life that seems to have quietly withdrawn. Here, in these simple and rustic hamlets, the murmur of social life has long since disappeared, swept away by the silent waves of time. |

|

|

| This corner of Isère still carries, like a distant whisper, traces of the influence of the Order of the Templars. Their power resonated strongly in the region, with numerous commanderies scattered throughout. Among them, the one at Bressieux was established at the place known as Le Temple. Yet, centuries have erased almost all traces of their presence, just as they have of the castle belonging to the powerful Bressieux family, whose ruins, ghostly sentinels, continue to dominate the town from their promontory. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the road moves away from the hamlet, running along walls of pisé and rolled pebbles, typical witnesses of the heritage of Bièvre and Dauphiné. These walls, with their robust simplicity, tell stories of peasant labor and local materials, extracted from the earth to build durable shelters. |

|

|

Approaching the site of Château de Bressieux, a keen eye will discover, through the oak foliage, the remains of the medieval castle, clinging to the hill like the tattered remnants of an ancient dream. These ruins demand a certain patience and an almost childlike curiosity to reveal their secrets.

| Lower down, along the paved road, a very real castle appears, noble and imposing, surrounded by a vast park. This elegant residence has belonged for generations to the Luzy de Pellissac family, silent guardians of this land where history and memory intersect. |

|

|

| The road continues its way to St Siméon-de-Bressieux, sliding gently toward the heart of the small town, inhabited by some 2,800 souls. This lively center offers a striking contrast to the dreary landscapes left behind. |

|

|

| For the brave, the ascent to the ruins of the former medieval castle represents an opportunity to glimpse history. But the climb, over half a kilometer, requires an effort not everyone is willing to make. Those who prefer to stay at the town’s level will find much to ponder in the remnants of the Girodon silk factory. Founded in 1848 by Alphonse Girodon, this once-thriving plant employed nearly 1,000 workers. Although it closed in 1934, it leaves behind an industrial building steeped in nostalgia. Around this vestige of a laborious past, the silence of vanished craftsmanship resonates like a muted lament. |

|

|

| The locality, humble like so many others in Isère, still hides unexpected treasures. Among them, bourgeois houses, discreet traces of a prosperous era. The church, rebuilt in the 19th century to replace a ruined structure, and the elegant town hall, accompanied by its school dating from the early 20th century, bear witness to a desire to reclaim a certain grandeur. |

|

|

| Finally, the route prepares to leave the Bièvre plain without regret. It begins a tiered ascent, climbing toward the Chambaran plateau. At the height of Chemin des Chênes, the Via Adresca branches off, abandoning the main route to venture toward the outskirts of the town. The direction is clear: Marnans, 7 kilometers away, calls to continue the journey. |

|

|

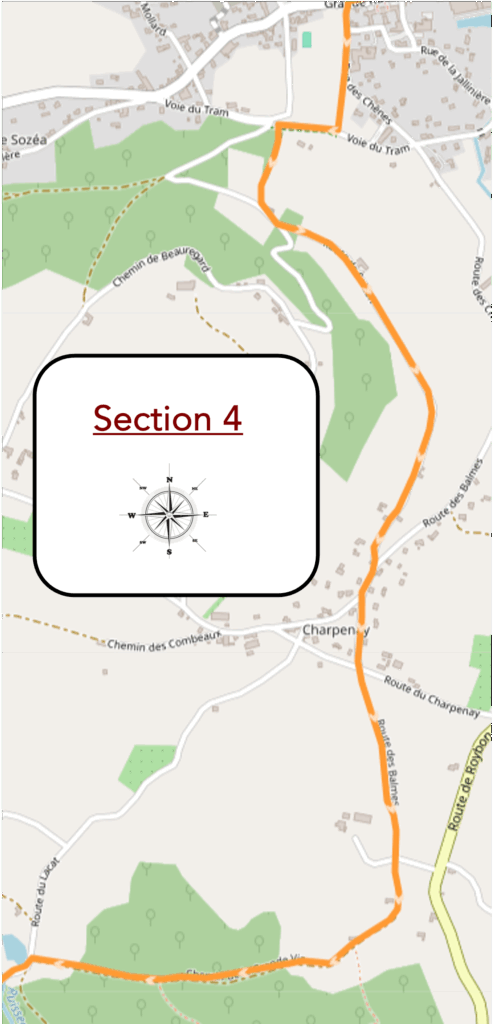

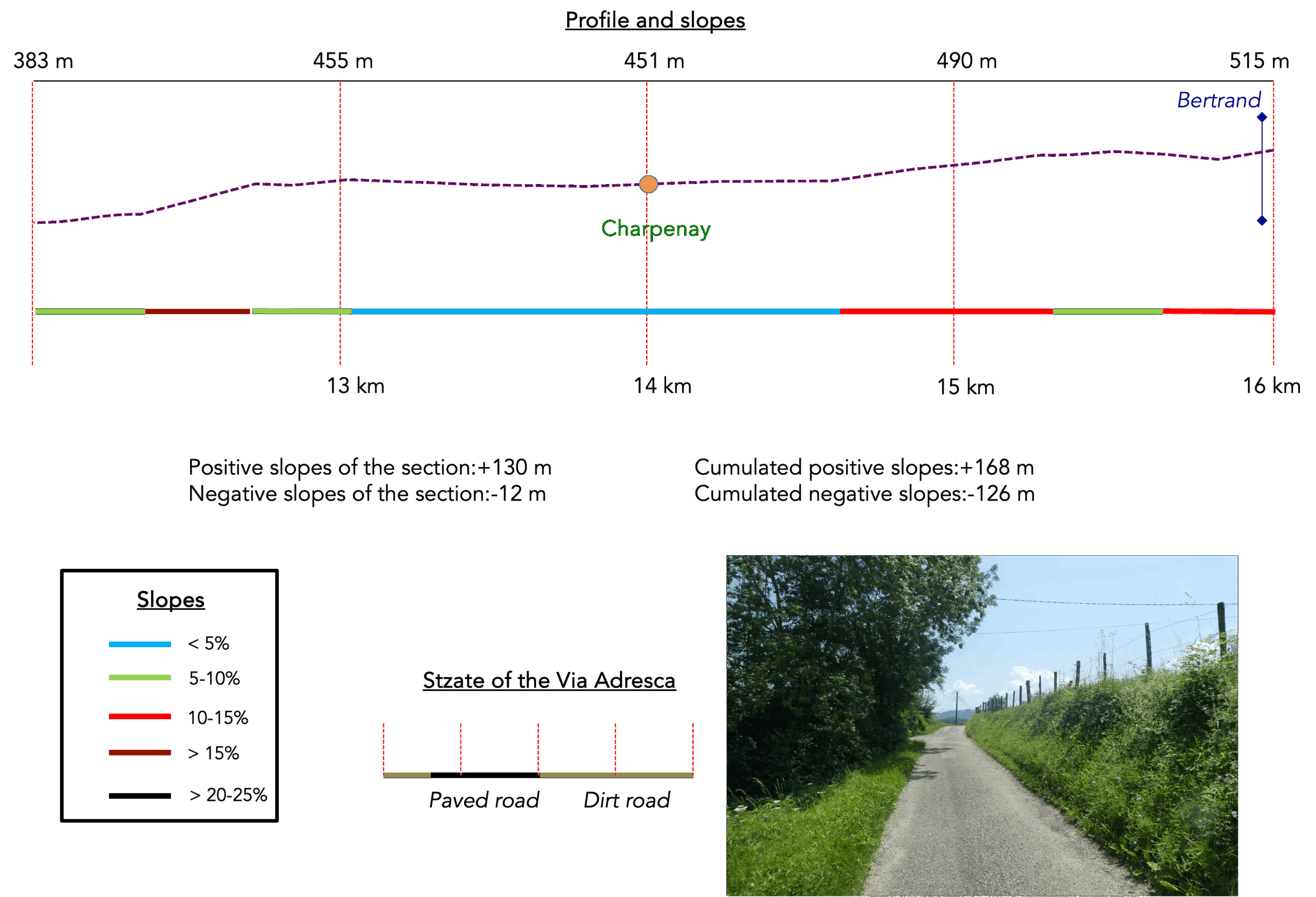

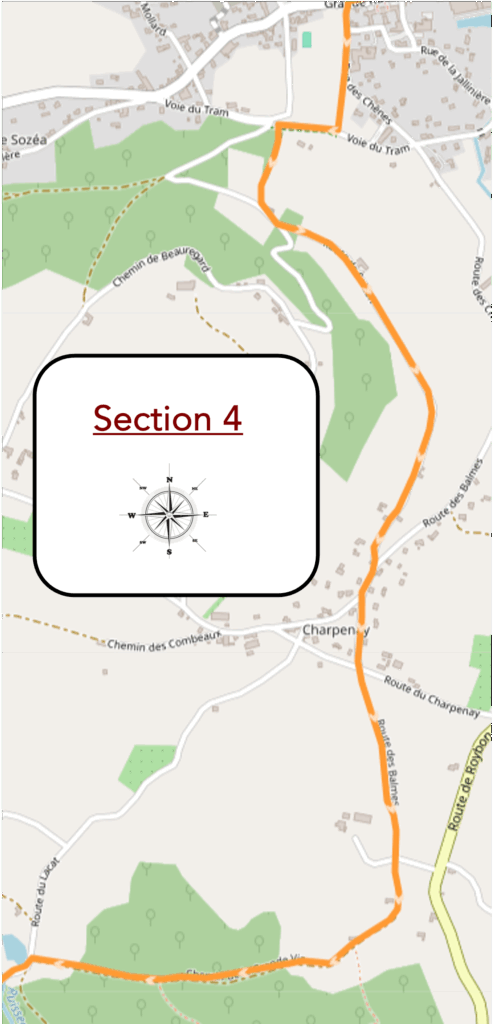

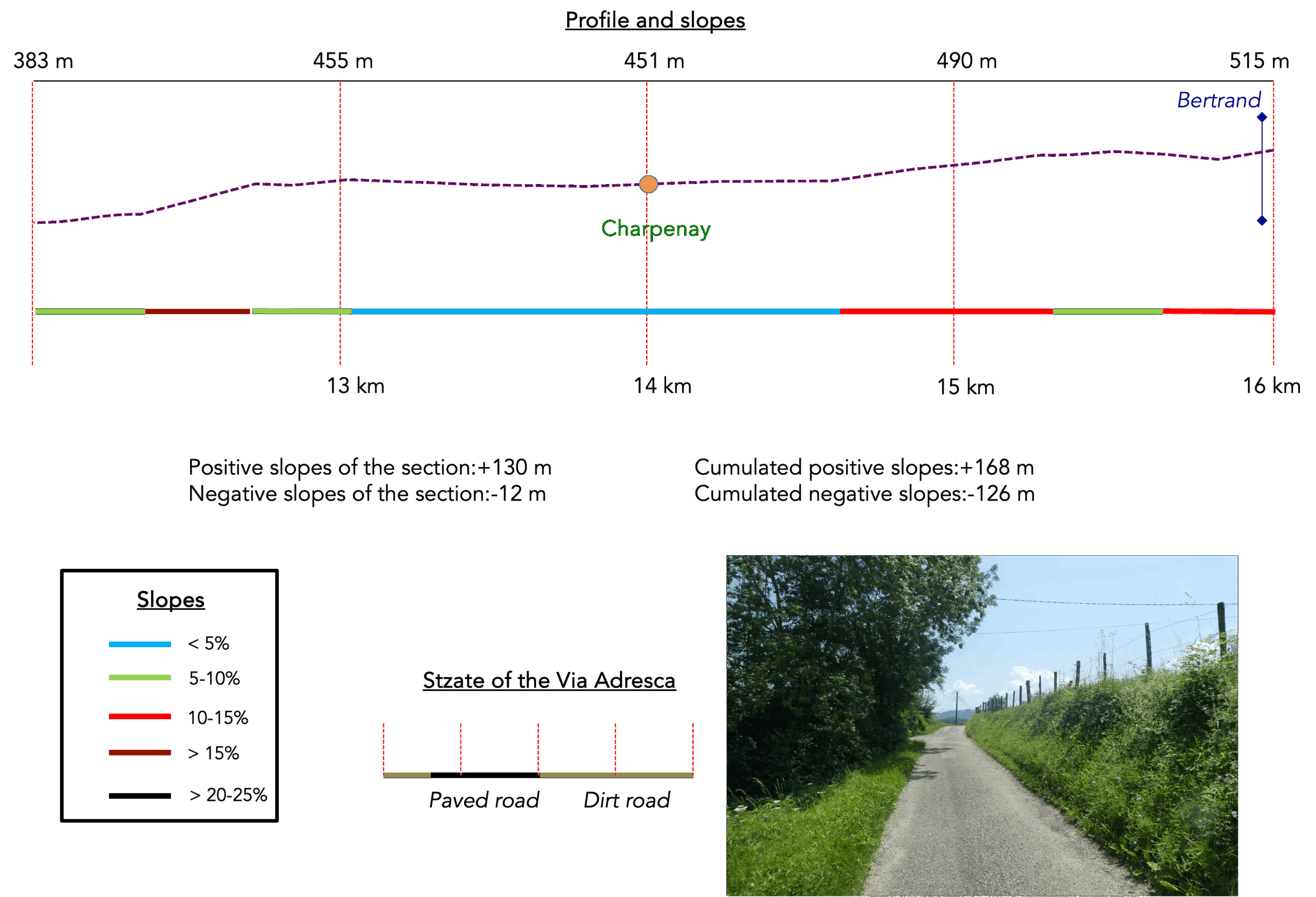

Section 4: Climbing towards the Chambaran hills

Overview of the route’s challenges: The climb towards Charpenay presents a difficulty, though not a major one.

| The route begins under the benevolent shade of trees, their foliage weaving a veil of soft light. It passes by a kindergarten, an imposing building where echoes of children’s laughter still linger, before encountering a manor house. This stately home, majestic in its restraint, sits at the heart of a large park, where lofty treetops whisper their secrets to passersby. |

|

|

| A winding trail then slopes up, skirting the fences of the residence. It enters a woodland dominated by sturdy oaks, the timeless rulers of the area, accompanied by a court of vigorous beeches, welcoming maples, and generous chestnut trees. The dense, vibrant hornbeam hedge here creates a cocoon of shadow and light, a refuge for souls seeking serenity. |

|

|

| As the climb continues, the ground is adorned with a constellation of pebbles, silent witnesses to the region’s geological history. These stones, smoothed over millennia, carried by glaciers of the Quaternary era, form a mosaic telling the ancient dance of the ice. Although you’ve left the Bièvre’s pebbles for those of Chambaran, their nature remains unchanged: polished relics of a bygone era, nestled in often barren moraine soil. |

|

|

| Higher up, the trail briefly joins a discreet paved road before reaching an iron cross, elegantly placed amidst the foliage. It overlooks walls built of rounded pebbles, a vision of peace and faith nestled in the intimacy of nature. |

|

|

| However, the trail does not relent. It continues climbing, contending with tangled roots, rebellious stones, and ruts carved by runoff water. Despite two weeks without rain, the section, first in the woods, then in the wild grasses of a clearing, resembles a dried-up torrent. It’s an intriguing sight, hinting at the chaos that rain could unleash here. |

|

|

| At the place known as Soizon, the path joins a paved road bordered by a quiet woodland. Here, vehicles are rare, and silence reigns. |

|

|

| The road climbs gently, winding between verdant meadows and shaded woods, revealing a soothing panorama: the Bièvre valley stretches below, punctuated by St Siméon-de-Bressieux, its apparent calm inviting contemplation. |

|

|

| The hills soften further, sketching a gentle curve under a clear sky. The atmosphere here is cheerful, welcoming, almost conspiratorial. Ash and oak trees stand as sentinels, while above, a dense and dark forest looms, imposing and mysterious. |

|

|

| A pisé farm then stands by the road, a bucolic tableau of an agricultural past. Here, meadows dominate, yet the land betrays a certain harshness, its meagerness revealing its limits. |

|

|

| Further on, the road approaches the hamlet of Charpenay, a scattered village where the first impression suggests inhabitants from diverse backgrounds, not just farmers. The scattered houses, wrapped in simplicity, tell the story of a place where time sometimes seems suspended. Crossing a more compact village, the road borders modest homes, discreetly hidden behind hedges of thuja, green screens of quiet privacy. |

|

|

| The road eventually reaches the Croix Breynard, a discreet sentinel planted in this peaceful landscape, five kilometers from Marnans. These crosses, omnipresent in the region, silently recount tales of popular devotion rooted in daily life. From this point, the Via Adresca avoids villages, preferring to wander between shadowy forests and open countryside. |

|

|

| A path gently enters the meadows, bordered by majestic hedges of ash trees standing like green sentinels. The landscape here breathes rustic simplicity, inviting one to savor the charm of true countryside, far from the turmoil of the modern world. |

|

|

| At the place known as Grande Vie, a small paved road winds between fields of soybeans, radiant sunflowers, and verdant pastures. It heads toward the Bois de la Porte before continuing towards Combe Bajat, where the promise of shaded woodlands becomes more prominent. |

|

|

| The road then begins to slope up slightly, never becoming demanding. It reaches its height for a pathway at the edge of a dense and exuberant forest, a vibrant natural sanctuary. |

|

|

| Here, it’s a true delight for the feet to tread on the pebbles of the Chambaran moraines, spiritual cousins to those of the Bièvre traversed earlier. These rounded stones, relics of a distant Ice Age, provide an almost musical texture underfoot, reminding walkers that the Via Adresca is not without such « crunchy » sections. Enough to delight hikers seeking tangible and authentic sensations. |

|

|

| However, at times, the pebbles grow scarce, almost as if erased. Perhaps the largest among them were taken, recovered to build the walls of nearby houses. But they quickly reappear, faithful to the geological cycle of Chambaran’s soils, as if the earth itself were playing hide-and-seek with history. |

|

|

| The forest surrounding these places is both dense and welcoming. The trees, towering as if to touch the sky, compose a realm where beeches, hornbeam shoots, maples, and chestnuts reign supreme. The oaks, for now, are rare, but the silent competition among species, especially young chestnuts, offers a lively and almost theatrical spectacle, common to the Dauphiné woodlands. |

|

|

| Soon after, the path leaves the deep woods of the Bois de la Porte, emerging onto a bright clearing. There, amidst the wild and peaceful nature, a few scattered houses nestle, like solitary refuges in a sea of greenery. |

|

|

| The Via Adresca then connects to a small paved road, continuing towards new horizons. |

|

|

| You reach the entrance to the forest of Combe Bajat, a place where nature’s breath seems to intensify. The road, still modest, briefly invites you to follow it. |

|

|

Nearby, the Bertrand stream traces its discreet course, meandering alongside a small pond. This corner of nature, both wild and tranquil, feels suspended in time. The gentle beauty of this natural setting speaks silently, offering travelers a moment of simple yet profound wonder.

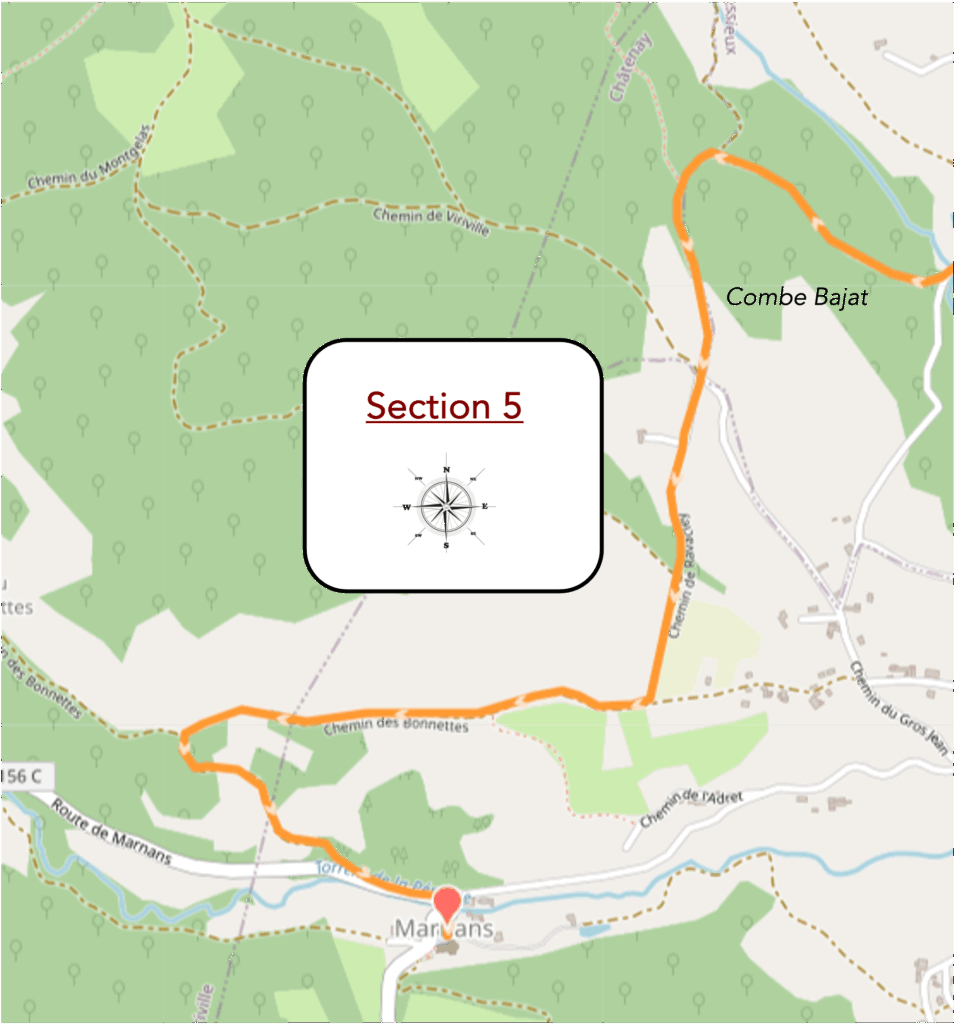

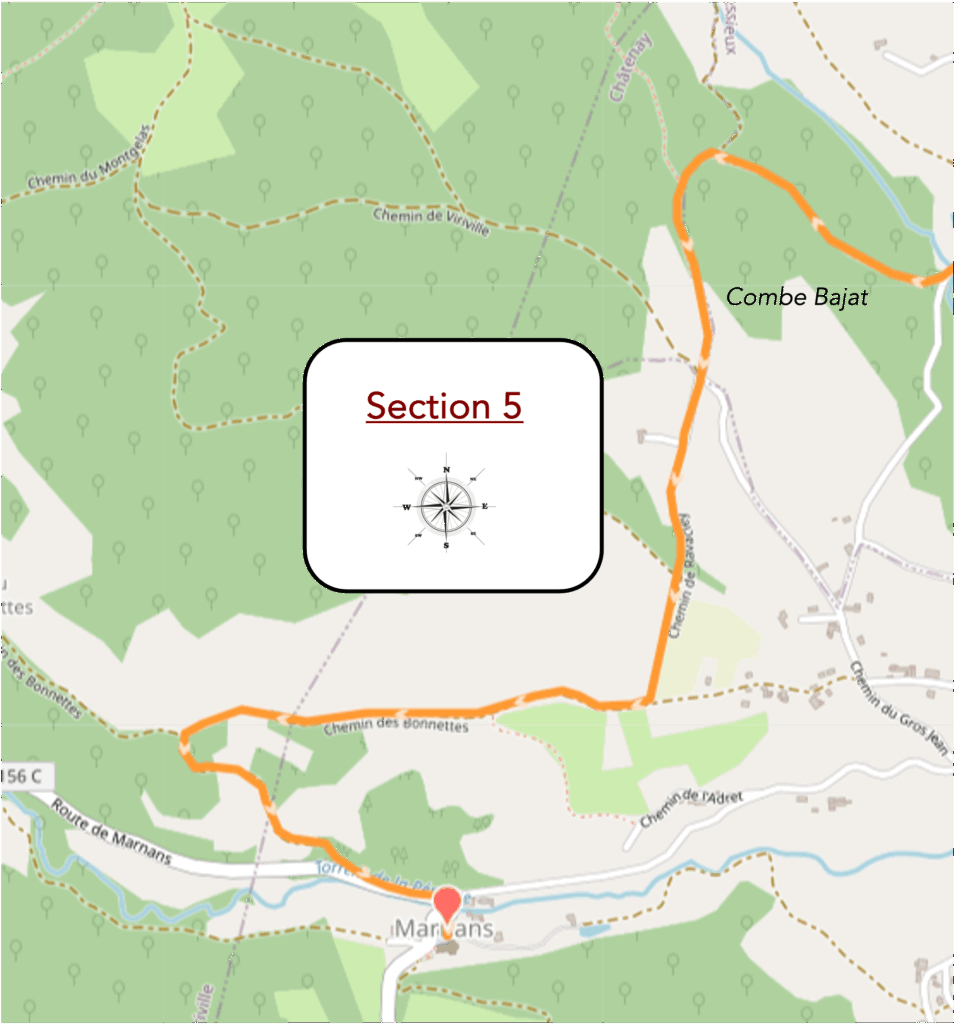

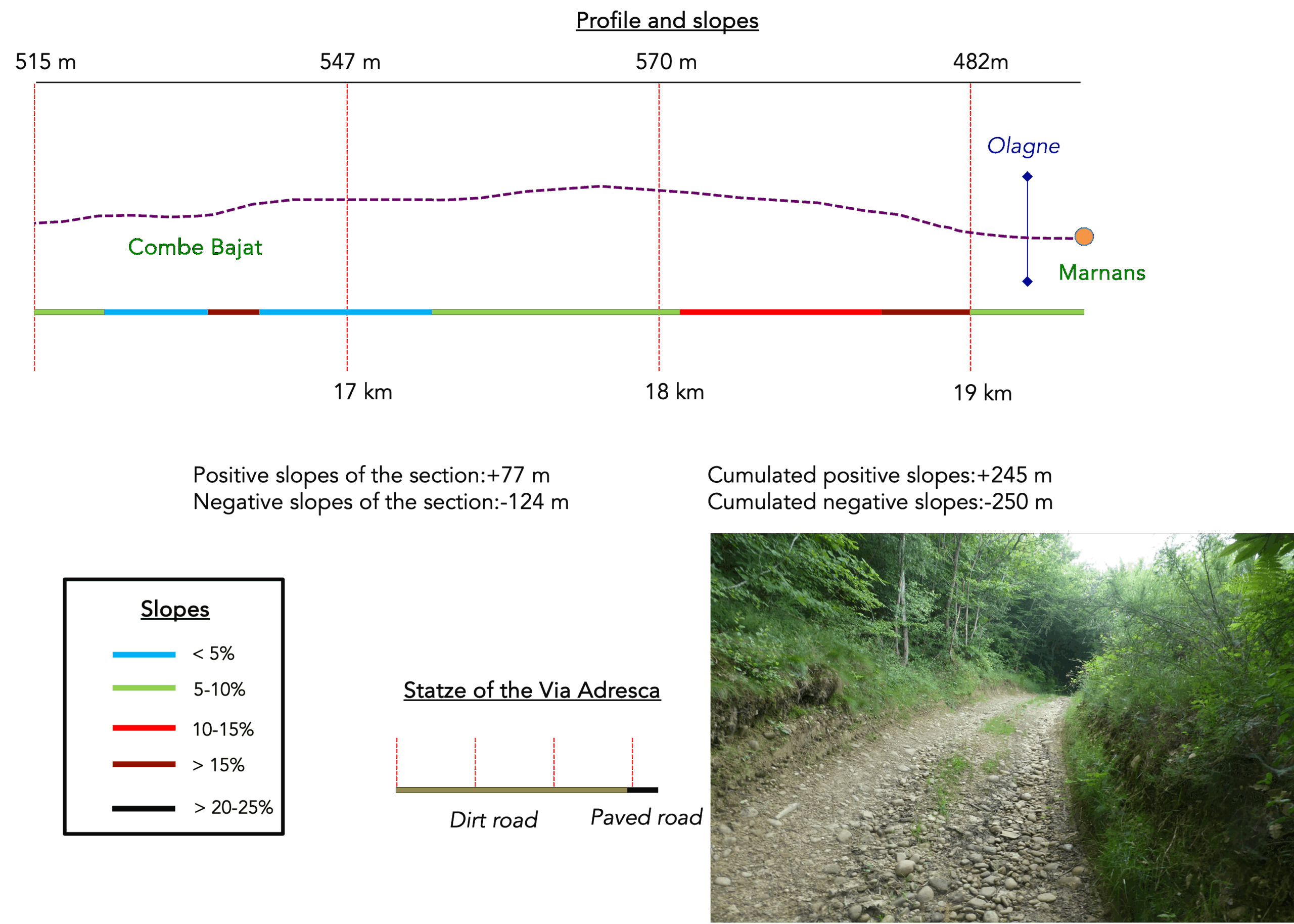

Section 5: A hill before descending toward Marnans

Overview of the route’s challenges: pronounced ups and downs, both ascending and descending.

| The Via Adresca does not linger long on the paved road. With a sort of discretion, it leads you to the delightful gravel paths of Chambaran. These stones, with their varied shapes, roll underfoot with an intriguing softness, especially when the slopes grow steeper. With each step, the ground seems to challenge and guide you, creating a dance of pebbles that almost makes you slide. The contrast between the exertion of walking and the smoothness of the stones is fascinating. This landscape takes on a unique, almost intimate quality, where nature plays its own game. |

|

|

| The path climbs steadily, never presenting overly harsh slopes. The incline remains gentle, rarely exceeding 10%. At times, sand replaces the stones, as though nature itself is trying to balance the scenery. This sand, shaped by ruts carved by forestry tractors, tells of humanity’s struggle with the land, leaving traces of their passage through this ever-living terrain. These machines have churned the soil, unearthing stones and leaving behind a mix of mud and moisture. The area becomes marshy, but with each step, you can feel the earth vibrate with a history it refuses to forget. |

|

|

| Yet, most often, the pebbles reign supreme, under the shade of wild chestnut trees. These trees, uncultivated and untouched by agricultural refinement, offer only meager fruits. Despite their frail appearance, they embody the resilience of this landscape, a land that refuses to be easily tamed. It’s easy to imagine that the locals, too accustomed to this untamed nature, see little use for the bitter fruits, their coarse taste fading into the wildness of this terrain. |

|

|

| A bit farther up, the Via Adresca reluctantly leaves the forest gravel behind, and the path transforms like a painting shifting its colors with the climb. |

|

|

| Here, the route opens onto meadows and fields of oilseeds: soybeans and sunflowers, the only plants hardy enough to survive this unforgiving landscape. The fields are scattered with stones, some visible, others buried deep, sinking into the earth as a reminder that, despite the apparent gentleness of the crops, nature maintains a firm grip. Clearing the land of stones is a constant battle, where the rocks always seem to stay one step ahead, sinking back into the soil like a persistent whisper in the silence of the fields. |

|

|

| As you progress, asphalt briefly appears, an interruption to the wilderness near isolated farms that seem to be lost in the vastness of the landscape. Then the path resumes, alternating between stones and grass, tracing a sinuous line between the elements, between humanity and the earth. |

|

|

| The path continues its ascent through meadows. Here, grand, majestic oaks stand solitary and proud. A few rare fields of cereal crops remind you of the perseverance of human cultivation in a nature that, at times, seems intent on erasing all effort. These fields, relics of an era when agriculture sought to conquer the soil, appear frozen in time, almost fragile in their persistence. |

|

|

| Then, the slope becomes steeper. The dance of large stones resumes with vigor, each rock presenting a new challenge. The path approaches the hamlet of Bonettes, where the terrain changes yet again. No longer a mere path, it turns into a scree slope. The climb becomes a true trial, each step a battle against gravity. The stones, ever more abundant, transform the landscape into a kind of organized chaos, a scene where nature reasserts its dominance over humanity, and where each stone feels like a small triumph of the natural over the human will. |

|

|

| Here, you reach a kind of high plateau, where the land seems to stretch and rest before heading toward new horizons. The Via Adresca does not head toward Les Bonettes but chooses a different route, following a paved road that stretches like a thin scar across the surface of this plateau. |

|

|

| On either side of the road, the landscape unfolds in a vast, almost infinite expanse. Beyond the meadows and canola fields, small clusters of chestnut trees form islands of wild growth, their shadows stretching to the edges of the groves. These chestnuts, proud despite their modest appearance, add a rustic touch to this peaceful plateau, almost frozen in its beauty. To your right, below, the Bièvre-Valloire plain spreads out, still present as a memory rolling by, a sea of greenery and fields merging into the horizon. |

|

|

| The Via Adresca continues its journey, taking on light undulations across this high plateau. The terrain becomes hillier, and towering oaks, silent giants, take over. The chestnuts, once dominant, fade into the background, making way for these majestic figures. The ground, firmer now, offers a more stable footing, less temperamental, yet the power of nature remains ever-present, constantly reminding you that here, it is nature that dictates the journey. |

|

|

| But now the asphalt becomes scarce, giving way to hardened earth reclaiming its territory in the vast meadows and oat fields. Noble wheat seems to avoid this soil, unyielding in its promises. Here, nature appears less generous, less willing to offer its fruits, as if the earth itself resists the human effort to subdue it. The crops seem to struggle against a soil that refuses to be conquered, a soil unwilling to surrender. |

|

|

|

|

| Further afield, the path begins to descend toward Marsens, plunging into a dense thicket where light struggles to filter through the tree trunks. As the slope becomes steeper, chestnut trees, awkwardly shaped with stunted fruits, reappear. Their scrawny shoots linger in the undergrowth like traces left by time. Here stands a peculiar monument, almost strange: a sort of ecological devotion, a gesture by the farmers who have made a habit of erecting their old vehicles as symbols of a connection to nature. Yet, these places are not beautiful; their appearance resembles true blemishes, and their presence seems an homage to the earth’s resistance, as brutal as the rust devouring the abandoned carcasses. These cars, left here by men, will rust endlessly, frozen in a bygone time. |

|

|

| Here, the slope becomes formidable, sometimes exceeding 25%, plunging the walker into a dense forest where chlorophyll oozes, saturating the air with a damp freshness. And as if to show those persisting in their advance that the path spares them nothing, pebbles grow increasingly numerous as you descend. It’s no longer just a walk; it’s an ordeal, a confrontation between man and nature, where stones become allies of gravity. The ever-slipperier pebbles seem to want to push you downward. Better to descend in good weather to avoid being engulfed by this sea of stones, smoothing each step and propelling you toward an inevitable fall. |

|

|

| At the base of this dizzying descent, the path finally emerges onto the paved road marking the entrance to Marnans, a village suspended between the heights and the valley. |

|

|

| The road, with its gentle slope, effortlessly leads to the heart of the village, just a few steps before discovering its soul. |

|

|

At the hamlet’s entrance, you’ll cross the Olagne, a small stream that meanders gently, like a discreet river running over pebbles, in the shadow of the mountains. It, too, seems to have decided to blend into the valley, sliding into the hollow like a well-kept secret, a soft murmur in the great silence of nature.

| Marnans is a discreet village, a place where a few houses bloom gently around the church, nestled against the building that peacefully watches over the valley. The paved road running through the village is so rarely traveled that one could almost hear the wind’s breath caressing the stones. The local inn, modest yet welcoming, invites conviviality. Dining there is a pleasure, and sleeping there a blissful experience in a calm seemingly suspended in time. In a region where accommodations are as rare as a hidden treasure, one would be wise not to hesitate when the opportunity to stop arises. |

|

|

| The St Pierre church, standing at the village center, is striking in its simplicity yet beautiful in its essence. Its Romanesque architecture is subtly adorned with touches of Byzantine style, delicate additions lending it a certain lightness, almost ethereal. Its appearance evokes classic Cistercian churches: stripped-down, free of superfluity, a place where each stone seems consecrated to prayer. The construction of the building is generally dated between the 11th and 12th centuries, a silent testament to the faith that animated the people of the time. The church, in its simplicity, is nonetheless a masterpiece. Its tufa vault is exceptional, one of the finest examples of Romanesque art. The eye is lost in the finesse of its forms, revealing why it is considered a reference among buildings of this style. Behind the transept, three chapels are tucked into the apses like secrets preserved within the stone. Once, a cloister adjoined the church, but today only the memory of this meditation space remains, destroyed during the Wars of Religion in the late 15th century, a casualty of the region’s conflicts.

The history of this place intertwines with that of the region, and in this complex context lies the genesis of the church. Some writings suggest it was the Antonines, monks established at St Antoine-l’Abbaye, a little farther on, who built the original edifice at Marnans. However, others claim it was the Benedictines. The doubt remains, as it often does when discussing the origins of medieval buildings, where records fade with time. The earliest chronicles tell you the Benedictines were initially tasked with guarding the relics of Saint Anthony of Padua, kept at St Antoine-l’Abbaye, relics renowned for their healing powers, especially against gangrene caused by ergot poisoning. In 1089, Guérin de Valloire, struck by this terrible disease, then known as the « sacred fire », vowed to dedicate himself to the afflicted if he were healed. Miraculously cured, he founded, along with his father, the Brothers of Alms, a kind of hospital dedicated to Saint Anthony, to treat those struck by the rye’s curse. In 1247, the Pope decided to regularize this community, officially affiliating it with the Augustinian Order. Thus, Benedictines and Antonines, who had until then worked harmoniously, one praying, the other healing, saw their relationship fray until it erupted into open conflict. History then escalates, and the Pope, caught in a dilemma between the two orders, ultimately sides with the Antonines, ousting the Benedictines from St Antoine-l’Abbaye. This act marked a turning point for the area, a shift leaving lasting marks. The next chapter of this story awaits at St Antoine-l’Abbaye, where the echoes of this conflict resonate in the stones.

In Marnans, history weaves with threads of conflict long tearing the lands of the region. Here, the village likely witnessed the unrelenting struggle between the two orders, the Benedictines and Antonines, before the latter-imposed dominance over the edifice amid religious tensions and shifting alliances. Then came the Wars of Religion, a whirlwind of violence shaking the Dauphiné in the late 16th century, when the region, a hotbed of Protestantism, became a battleground for fierce, devastating clashes. The name of François de Beaumont, Baron of Adrets, still resonates as that of a formidable Protestant leader. His reputation for cruelty matched his fervor to silence the Catholic Church. The destruction of churches was his favored mission, and among his victims were the churches of St Antoine-l’Abbaye and Marnans, places of faith and resistance. It is here, amidst the fog of legend and yellowed chronicles, particularly one recounted by Vital Berthin, that another story of Marnans is written, where the soul of the village intertwines with the tragic events it endured. François de Beaumont, driven by an unrelenting thirst for conquest, marched toward Marnans with his army to capture the young prior, a staunch defender of Catholic faith. At his side marched Captain de Granges, a more moderate man, almost Catholic at heart, who tried in vain to dissuade his companion from harming the prior. Yet Beaumont, unyielding, ignored his pleas for clemency. Upon reaching the church, he found the prior had fled to a nearby hill. Undeterred, Beaumont ordered explosives to be set, lighting the fuse. The explosion shattered the stained glass, collapsing part of the wall in a cacophony of stone and dust. Seeing the catastrophe from afar, the prior hurried back and presented himself to the baron, begging for the church to be spared. Beaumont, enraged, ordered the roof demolished. In a final act of faith, the prior offered his life to save the church, but his refusal to convert to Protestantism sealed his fate. Soldiers shot him, yet he did not die immediately. Captain de Granges then intervened, tending to the wounded man and removing his clothes. At that moment, a miracle occurred: on the unfortunate’s garments, the image of the prior’s mother appeared. Moved, Beaumont immediately halted the church’s destruction. He cared for the wounded prior, and upon the prior’s death, respectfully closed his eyes before breaking into tears. The baron, shaken by this divine sign, abandoned his cause and turned to Catholicism, marking the end of an era for him.

This story, whether believed or not, still echoes in Marnans. Reflect on it the next time you step into the church’s great nave, where each stone seems to whisper tales of the past. |

|

|

| On another day, the innkeeper went all out. It was the Fête de la Musique, and the atmosphere was jubilant. Sausages grilled over flames, wine flowed freely, and laughter rang beneath the church’s arches. Dancing continued late into the night, the shadows of revelers blending with the flickering light of lanterns in a festive, convivial atmosphere. A suspended moment, a pure instant of joy in the heart of this quiet little village. Magnificent. |

|

|

Official accommodations on the Via Adresca

- Château de Montgontier, Gillonay; 04 74 20 25 78/ 06 84 64 92 56; Gîte, dinner, cuisine

- Chambre d’hôte Sous le Figuier, St Siméon-de-Bressieux; 07 82 64 99 57; Guestroom, dinner, breakfast

- Auberge de Marnans, Marnans; 09 56 30 58 17; dinner, breakfast

Pilgrim hospitality/Accueils jacquaires (see introduction)

- Gillonay (1)

- Brézins (1)

- St Siméon-de-Bressieux (3)

On the Via Adresca, accommodation options are almost always limited. You won’t be crossing the more touristy southern part of the Ardèche. Lodging is scarce, even for Airbnbs, and their addresses are not readily available. The list only includes accommodations directly along the route or within 1 km of it. The Amis de Compostelle guide, on the other hand, provides a comprehensive list of all available lodging addresses, as well as information on bars, restaurants, and bakeries along the route, even several kilometers away. For meals, you can take a break in Brézins or Saint-Siméon-de-Bressieux. At the end of the stage, the Hotel de Marnans is an option, but reservations are essential. Otherwise, you’ll need to continue on to Roybon to find a place to stay, although options remain limited there as well.

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 9: From Marnans to St Antoine-L’Abbaye |

|

|

Back to menu |