Astride the Franco Swiss Border

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

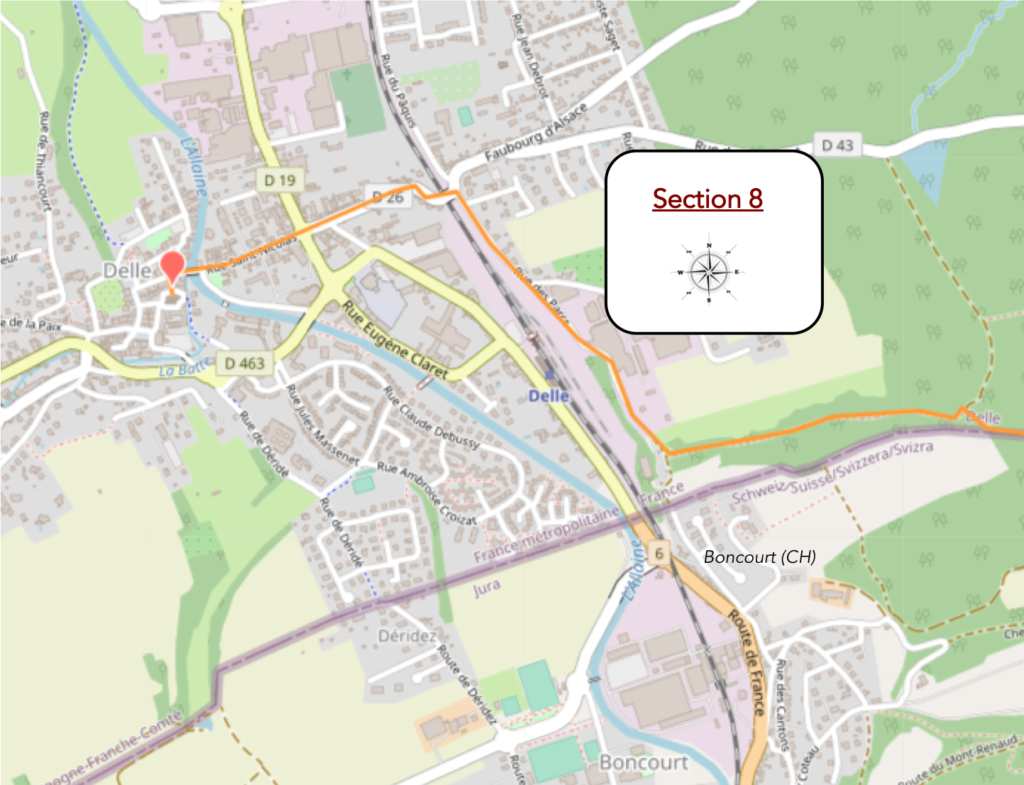

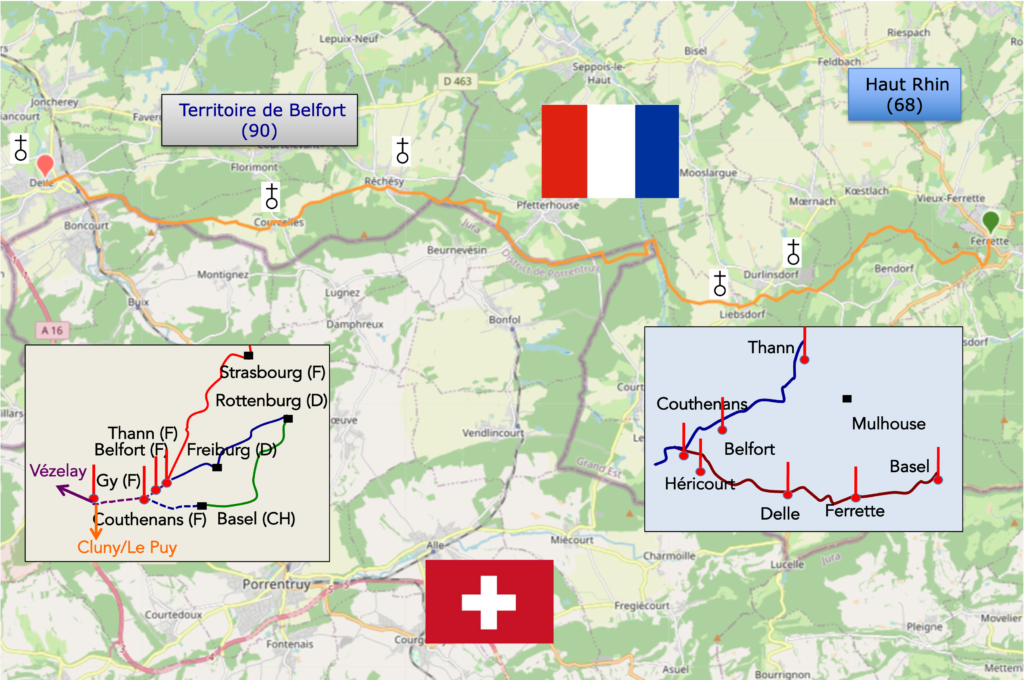

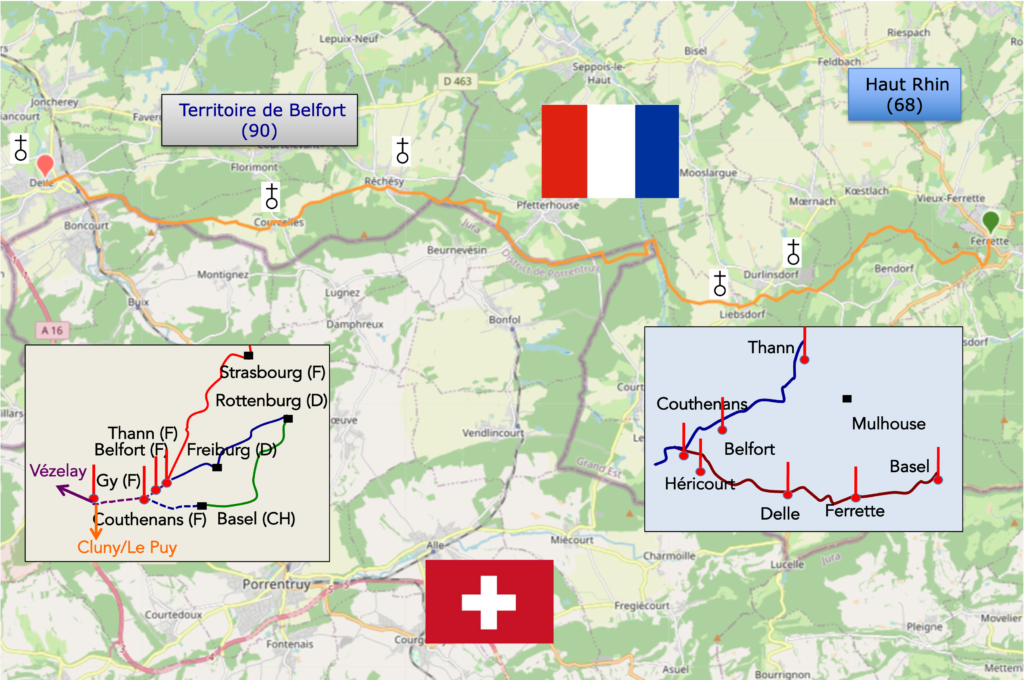

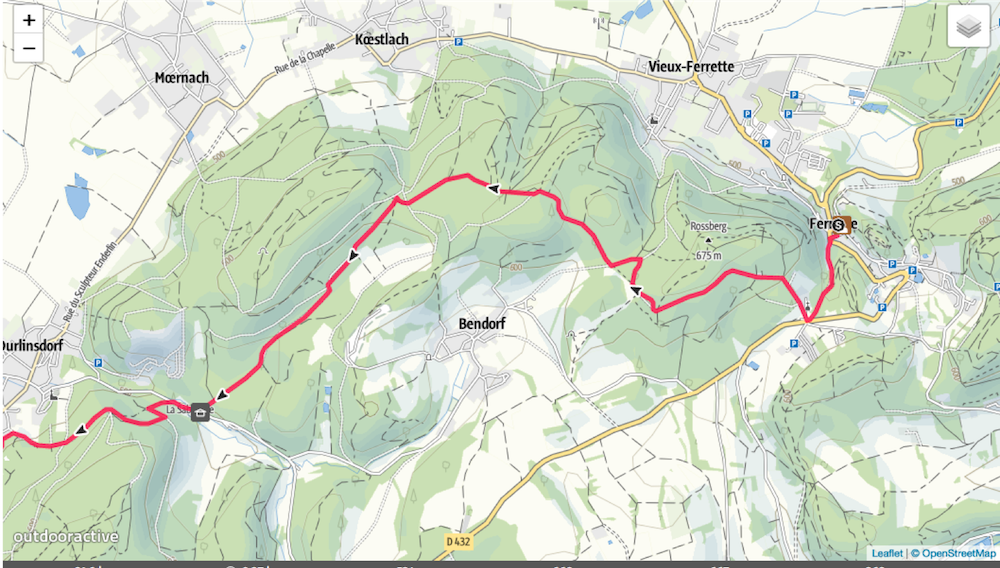

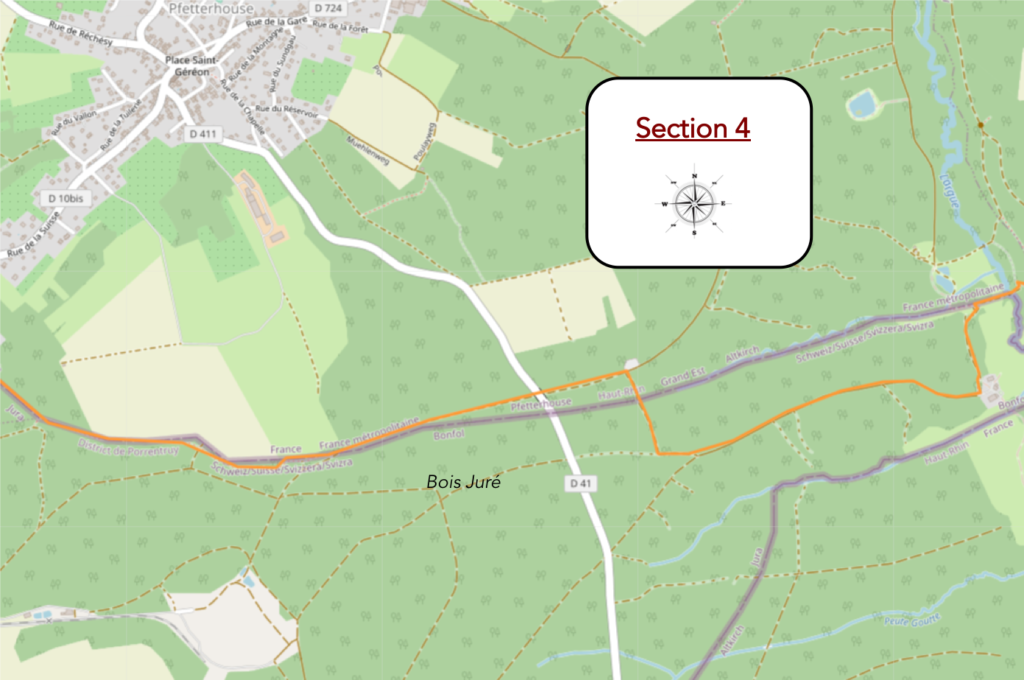

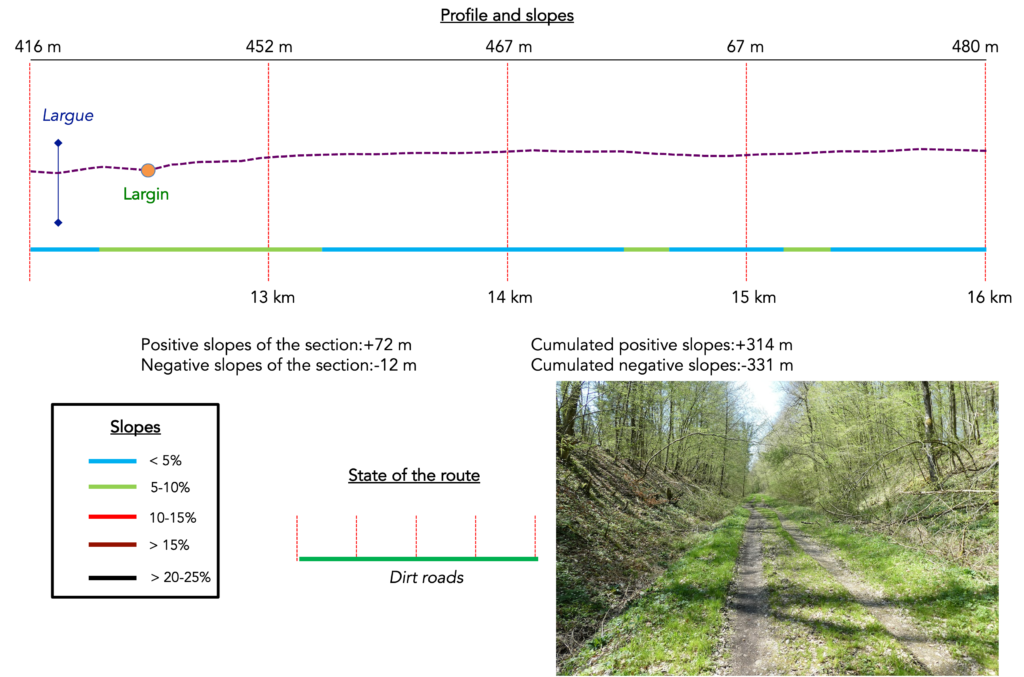

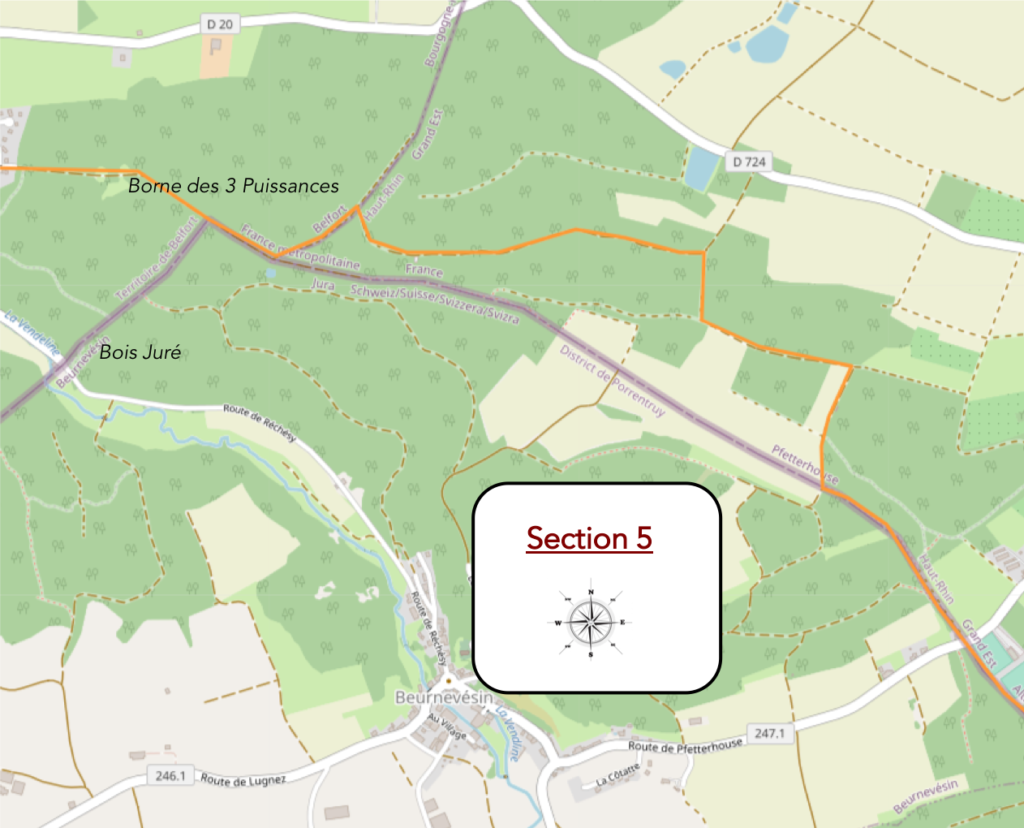

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

Pour ce parcours, voici le lien:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-ferrette-a-delle-par-le-chemin-de-compostelle-82122034

| This is obviously not the case for all pilgrims, who may not feel comfortable reading GPS tracks and routes on a mobile phone, and there are still many places without an Internet connection. For this reason, you can find on Amazon a book that covers this route.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page. |

|

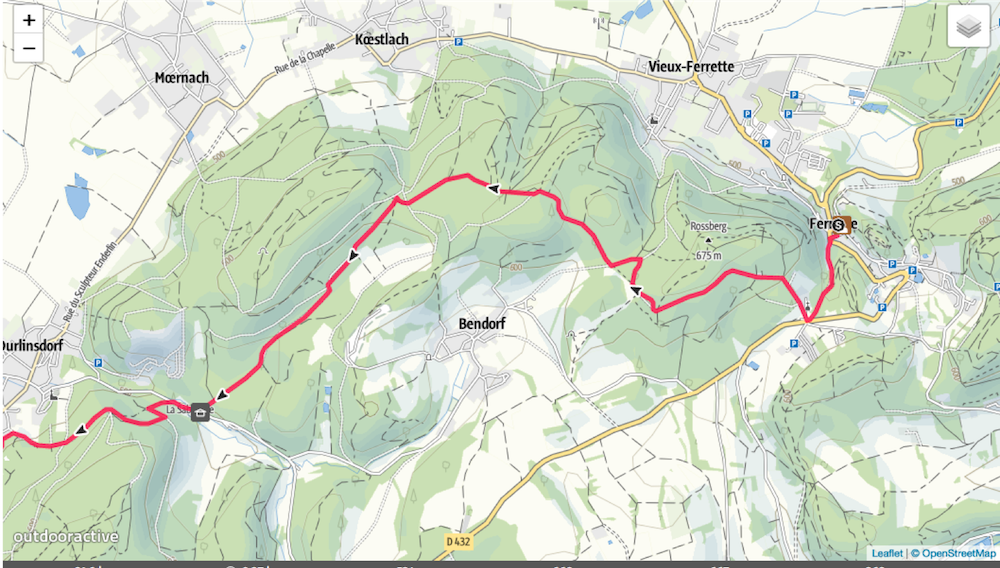

Today is a deep incursion into a territory marked by the turbulent history of the Second World War. It is an area where French, German, and even Swiss forces were long locked in tension, without any major battles ever taking place here. The war left its marks, but quietly: buried bunkers, forgotten barbed wire lines, discreet memorials. This landscape, often peaceful today, was once a buffer zone, a no man’s land where everyone kept an eye on everyone else. The route plays at crossing borders. You step over the line between France and Switzerland as easily as you would cross a path. You move from one country to another without realizing it, except for the style of the signs or the subtle differences in waymarking. This winding and hesitant path ends in Delle, on French territory, just a short distance from Boncourt, on Swiss territory.

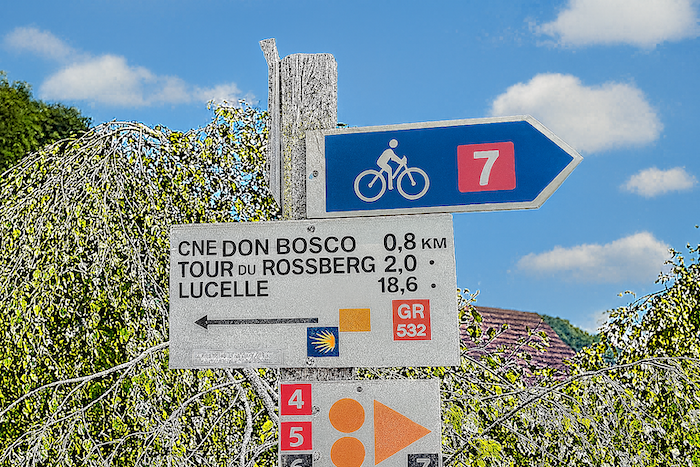

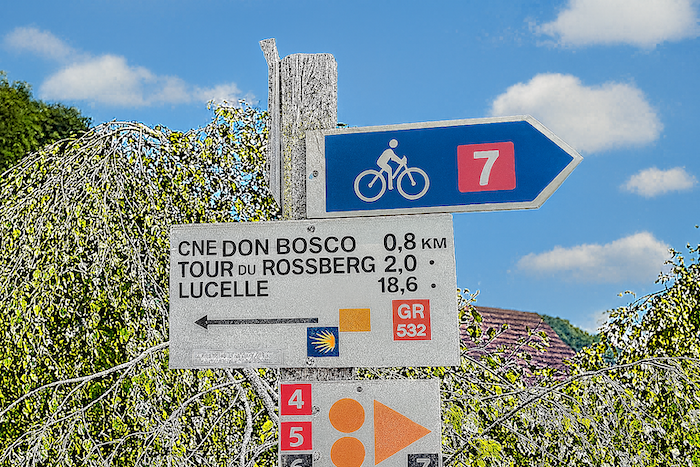

And here again, as on the previous day, there is a profusion of direction signs, a true inventory worthy of Prévert. You have to choose, sort, and focus. Because unfortunately it is not just about the names. The waymarking comes in an astonishing variety of shapes: circles, triangles, diamonds, rectangles, and in every colour imaginable. Red, orange, green, blue, a true kaleidoscope of paths for hikers, horse riders, or cyclists. At every junction, you must stay alert. Identify the right symbol, commit it to memory, and find it again further on. If you lose it, there is no doubt, you have gone astray. Turning back is sometimes wiser than pushing ahead at random.

How do pilgrims plan their route. Some imagine that it is enough to follow the signposting. But you will discover, to your cost, that the signposting is often inadequate. Others use guides available on the Internet, which are also often too basic. Others prefer GPS, provided they have imported the maps of the region onto their phones. Using this method, if you are an expert in GPS use, you will not get lost, even if the route proposed is sometimes not exactly the same as the one indicated by the shells. You will nevertheless arrive safely at the end of the stage. In this context, the site considered official is the European Route of the Ways of St. James of Compostela, https://camino-europe.eu/. For today’s stage, the map is accurate, but this is not always the case. With a GPS, it is even safer to use the Wikilocs maps that we make available, which describe the current marked route. However, not all pilgrims are experts in this type of walking, which to them distorts the spirit of the path. In that case, you can simply follow us and read along. Every difficult junction along the route has been indicated in order to prevent you from getting lost.

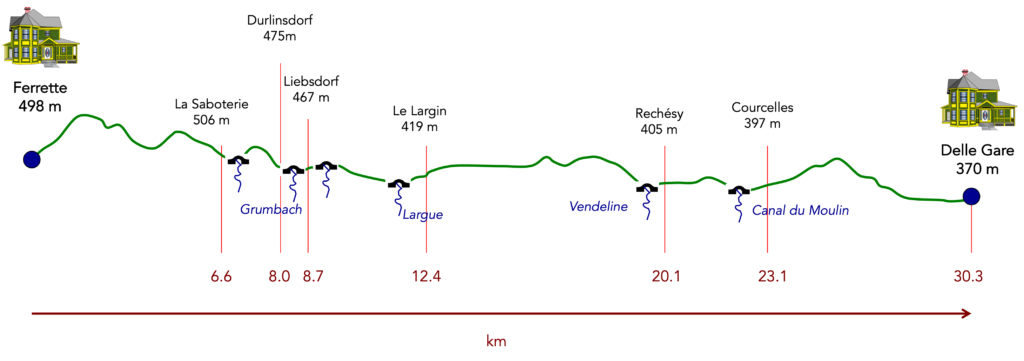

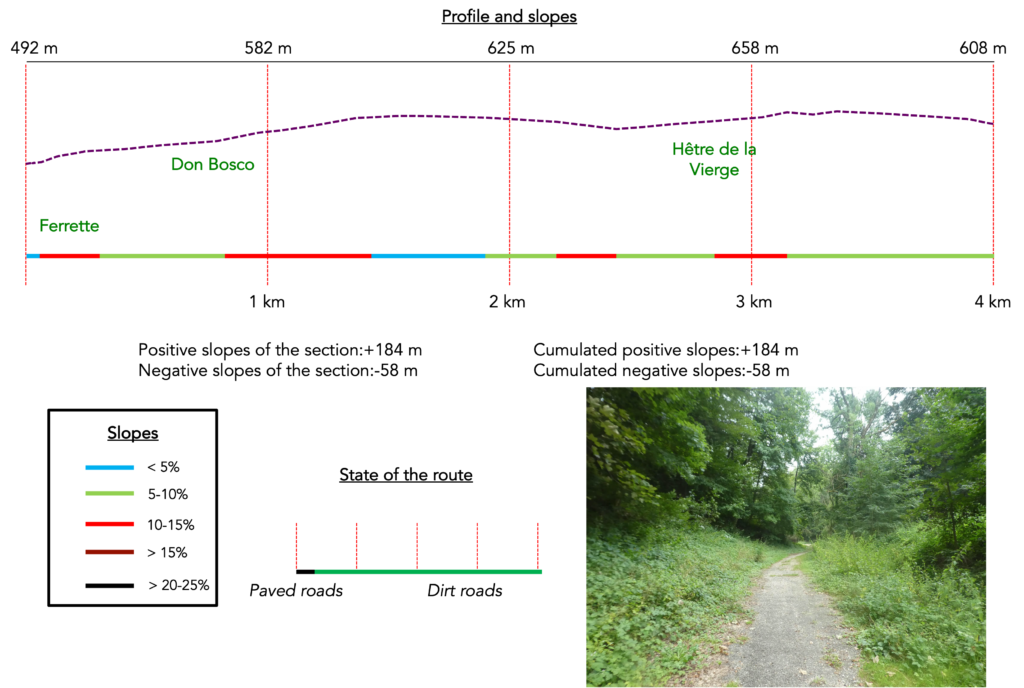

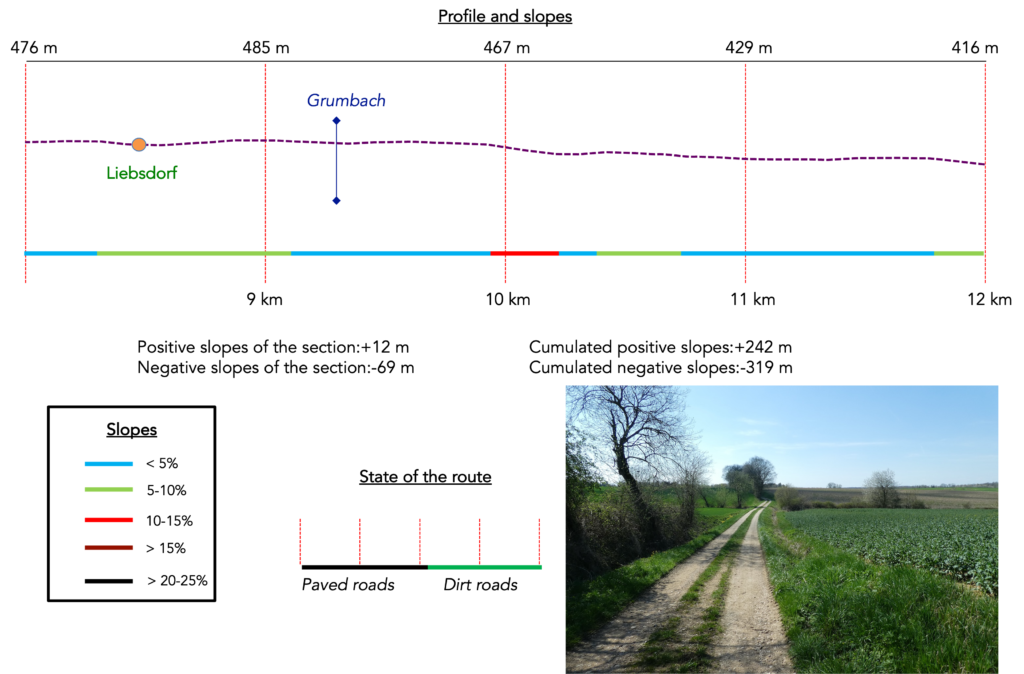

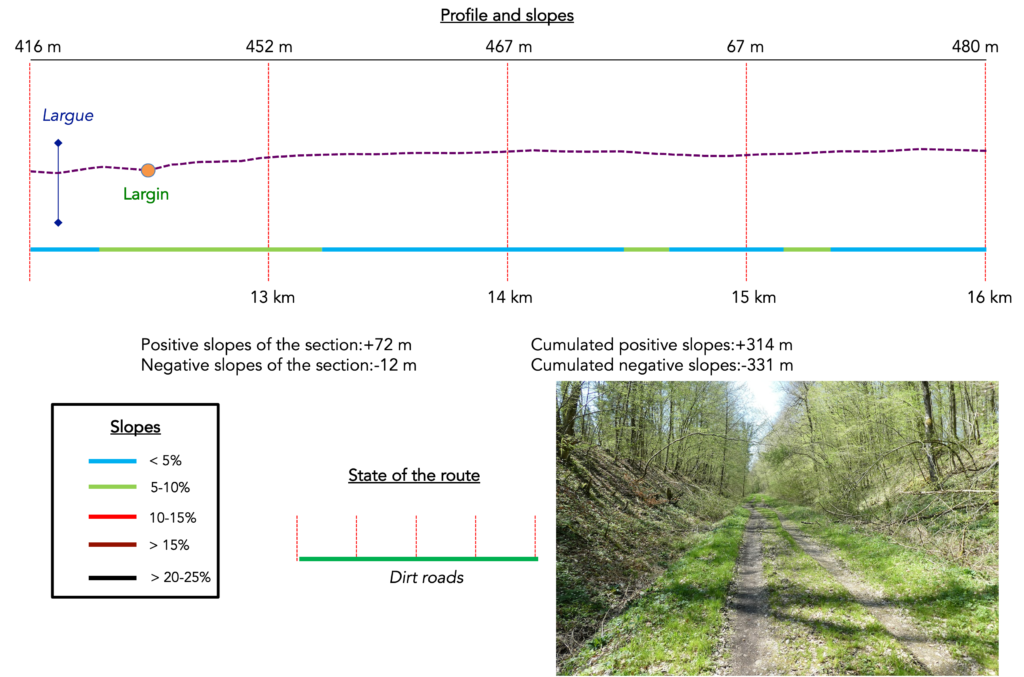

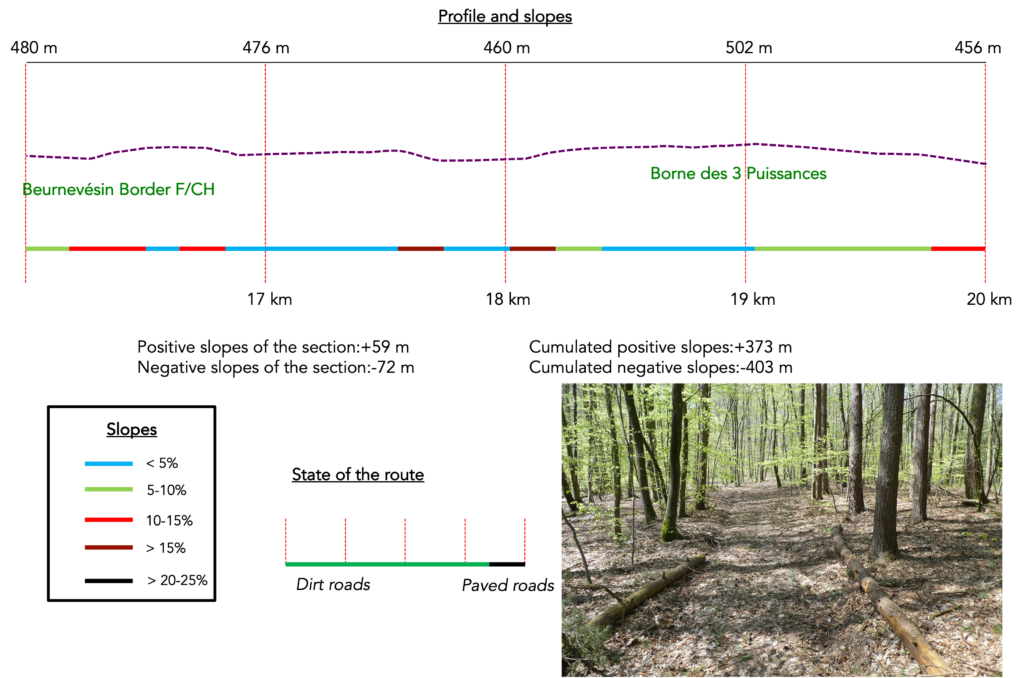

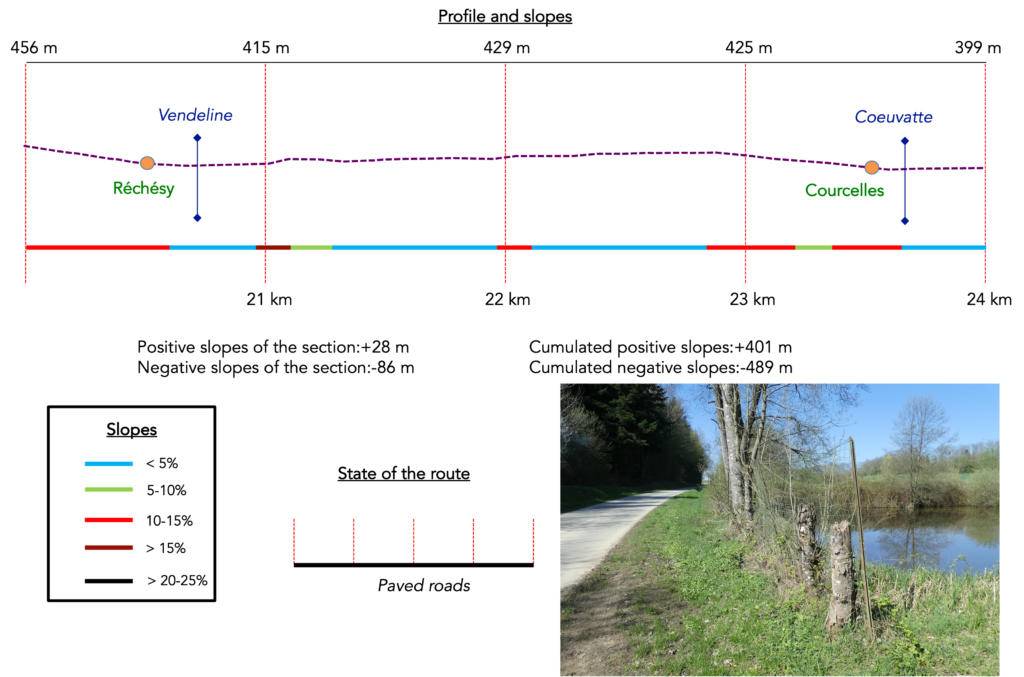

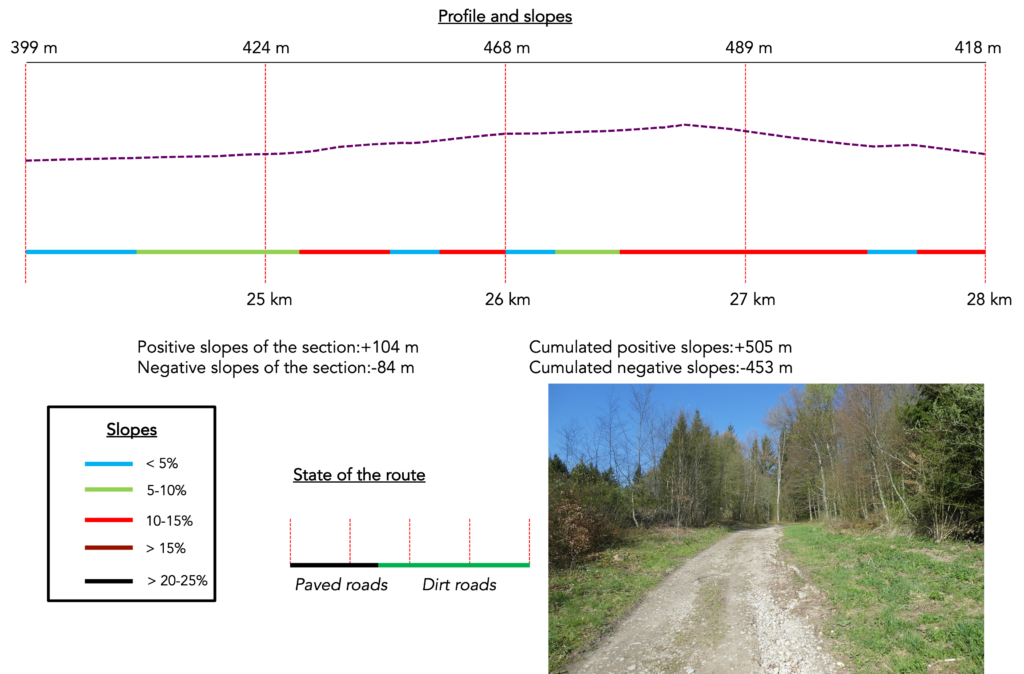

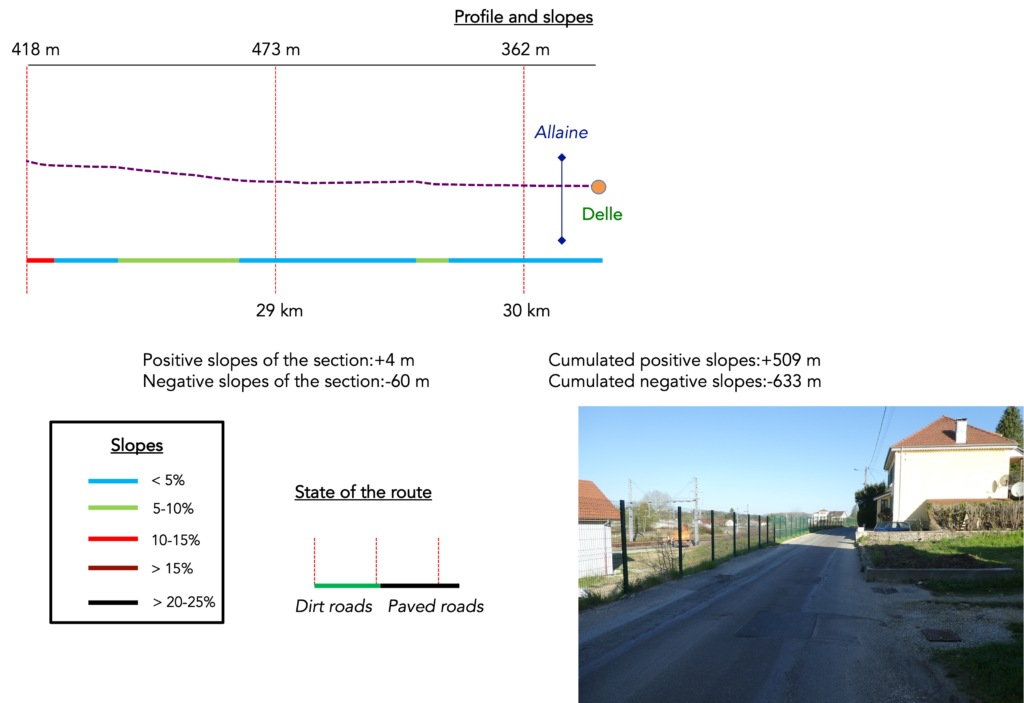

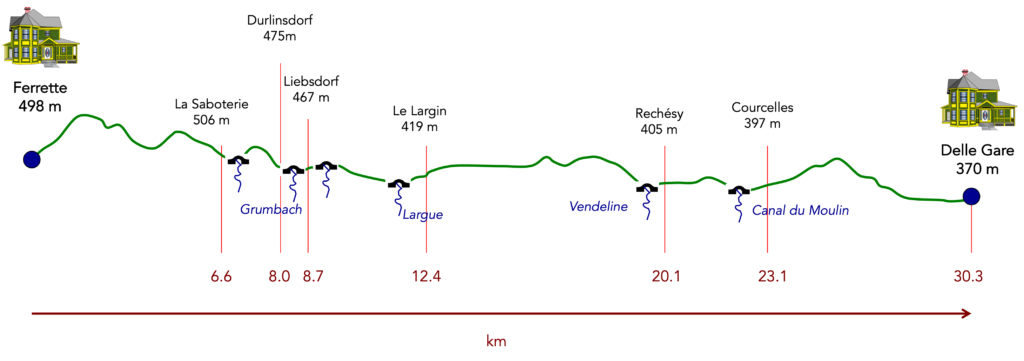

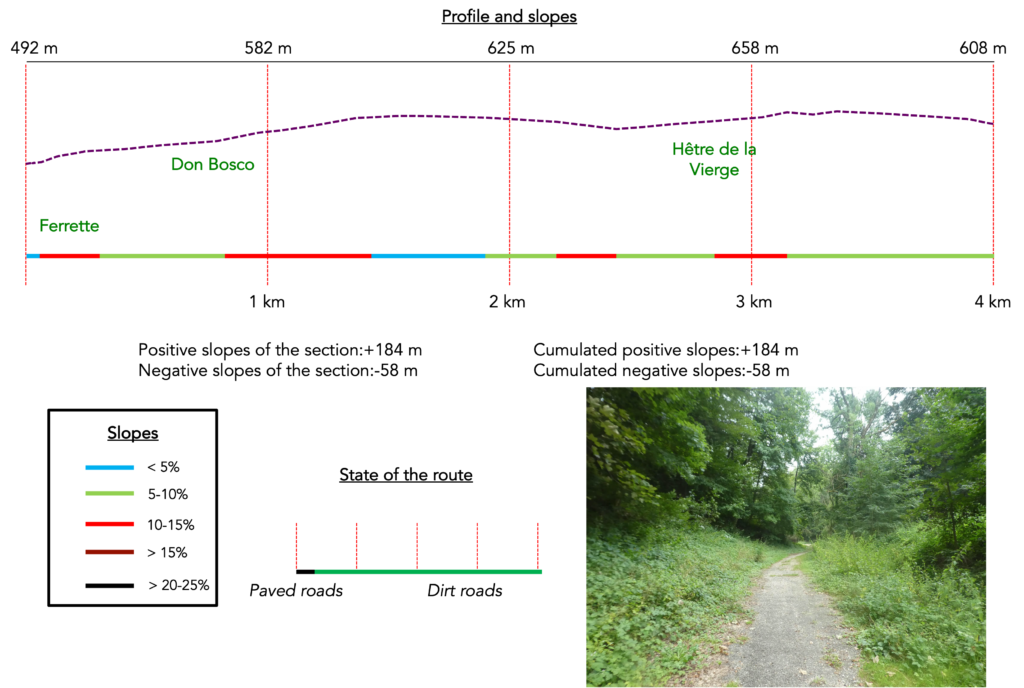

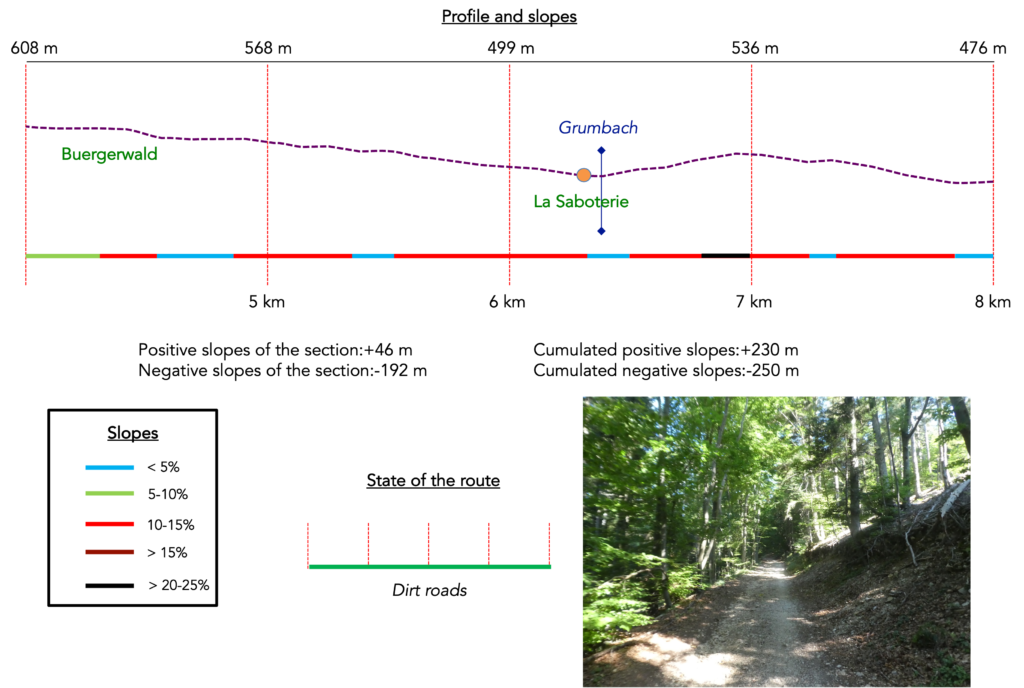

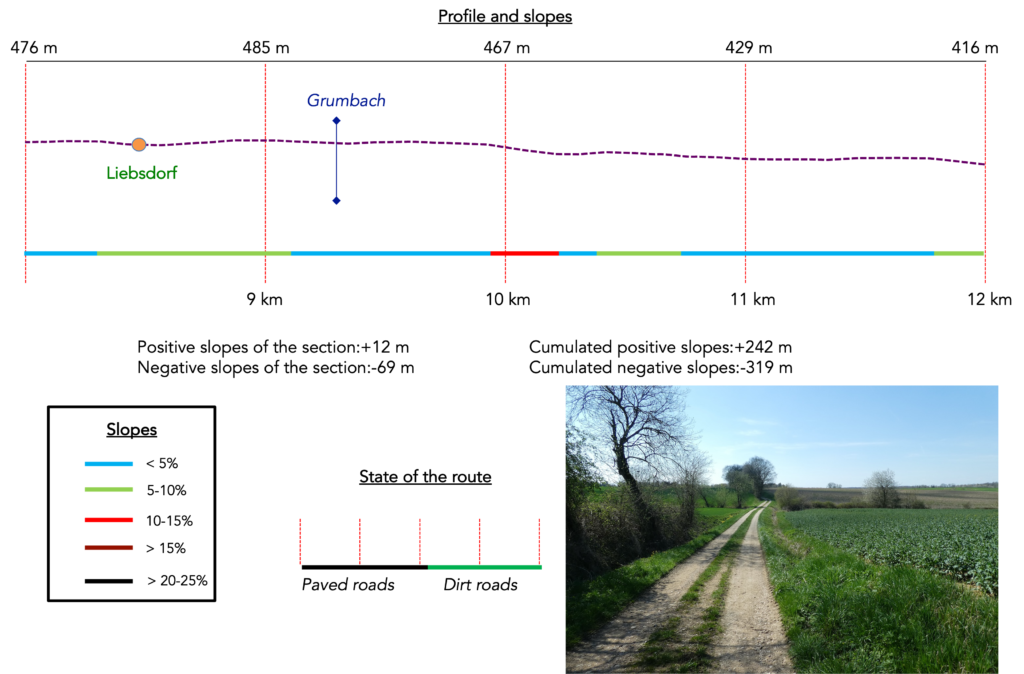

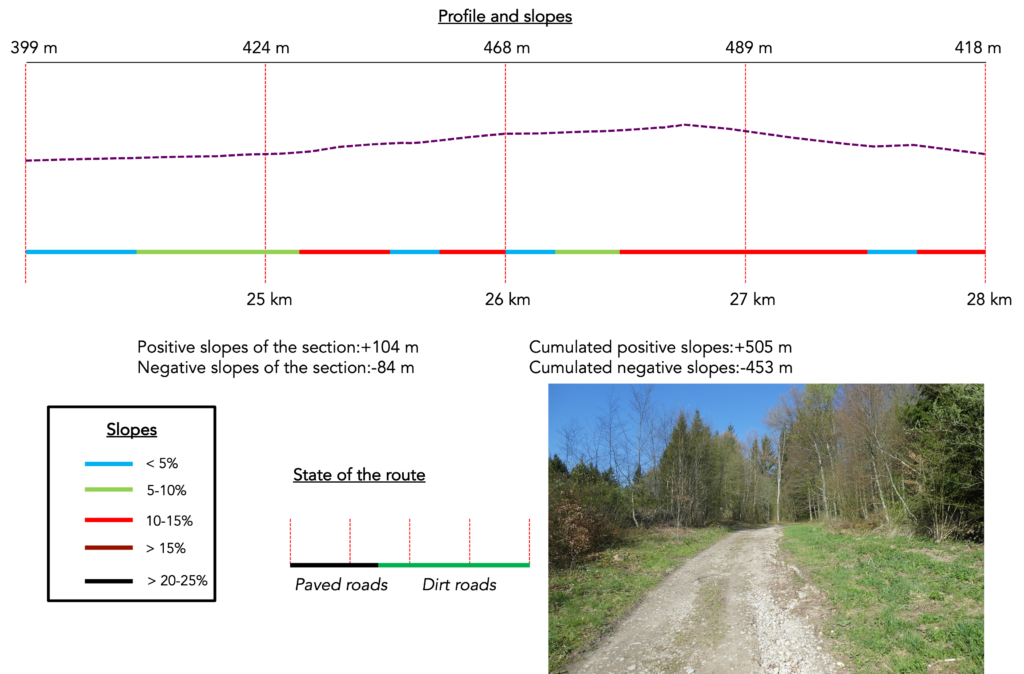

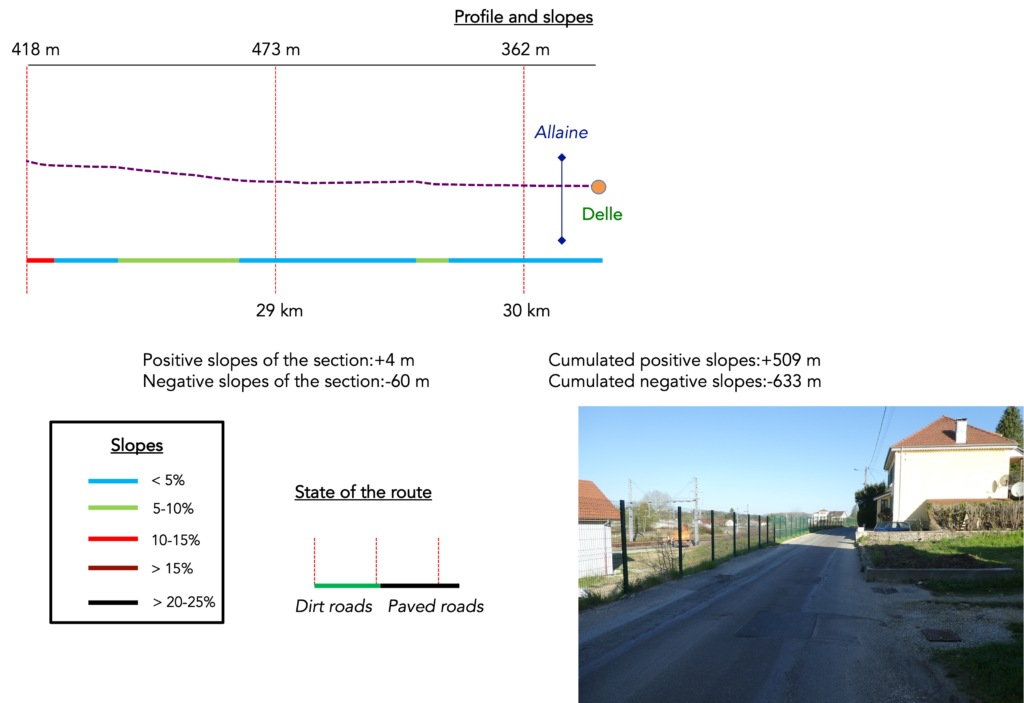

Difficulty level: Today’s elevation changes (+509 m / −633 m) are noticeable, especially at the beginning of the route when leaving Ferrette. After a long ascent toward the hills, the descent becomes steady toward Liebsdorf. Then come the roller coaster sections, and your legs get to work. This is not the Himalayas, but your thighs will feel it. Most of the time, the climbs are gentle. It is mainly in the wooded sections that the path sometimes rears up.

State of the route: Once again, this is a stage that pilgrims appreciate. Less asphalt, more earth. A true walking day just the way we like it:

- Paved roads: 8.1 km

- Dirt roads: 22.2 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

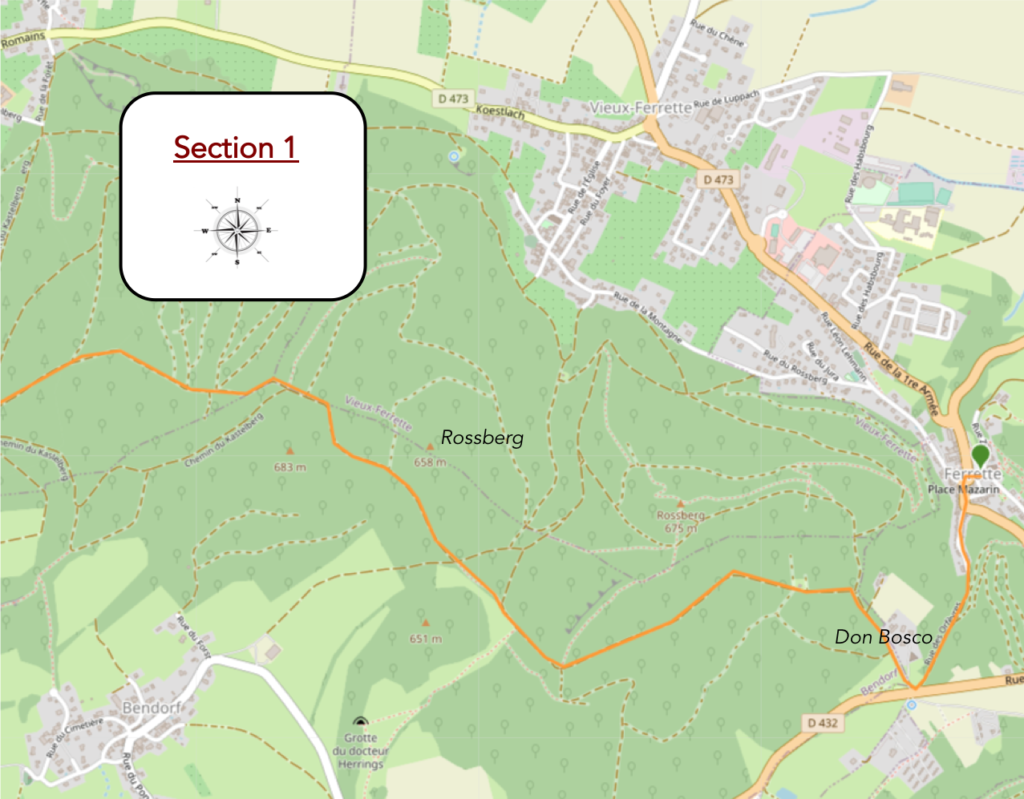

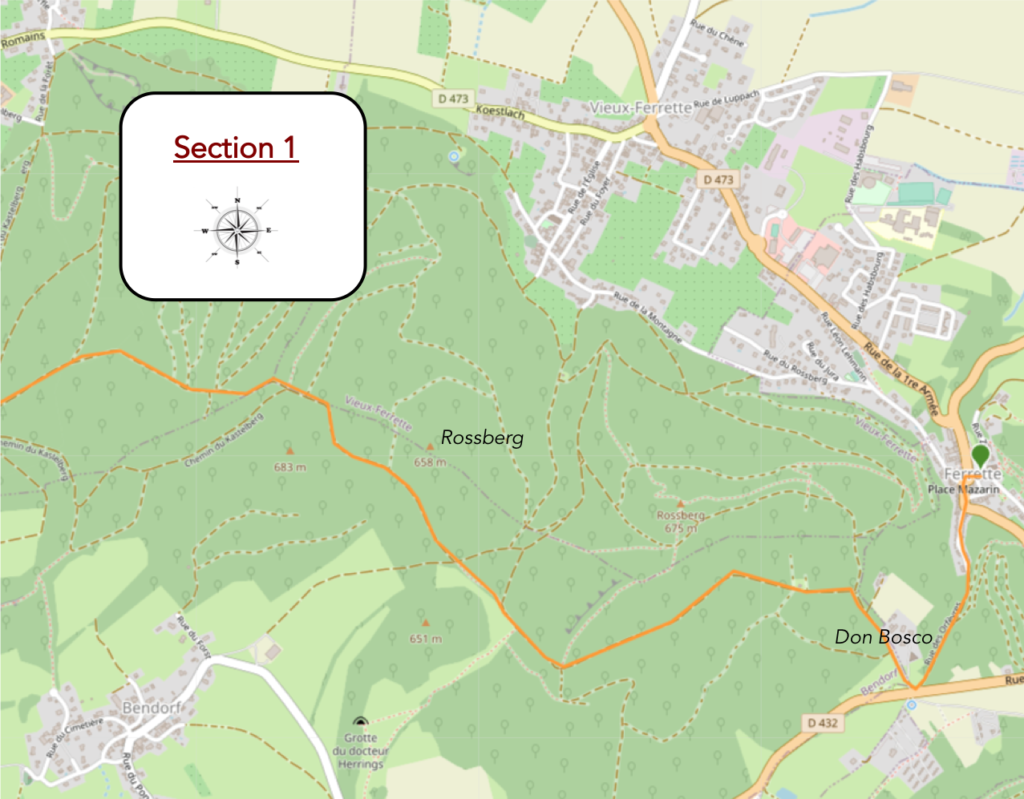

Section 1: A beautiful forest to cross, with the risk of getting lost

Overview of the route’s challenges: a leg-breaking route, often with marked slopes.

The day before, you arrived from the upper part of Ferrette via Rue du Château, then went down to the centre of the village, where the church and the shops are. In Ferrette, there are more paths than people in the street. Here is a brief glimpse, to give you a sense of it. Here, paths multiply like invisible veins, labyrinths of secret itineraries. Ferrette, a village of shadows and paths, offers an intimate geography, a discreet echo of the walker’s solitude.

| A slight confusion takes shape from the very start; a kind of colourful riddle the traveller’s eye must decipher. The famous GR waymarks, usually red and white, make a singular exception here, an orange and yellow rectangle replaces their usual sign, an unexpected flare in this graphic landscape. The GR532, then, appears in this strange outfit, while the direction to follow, for the seasoned pilgrim as well as the curious amateur, leads toward the mysterious Rossberg Tower. This route, recommended by the Friends of Compostela and symbolized by the famous scallop shell, plays hide and seek, the St James emblem appears only at major junctions or when one approaches Delle, like a discreet guide that sometimes slips away. In this profusion of signs, forks, and paths that intertwine through the village, finding the right road becomes a subtle challenge, the direction of Lucelle often serves as a polar star. Yet the journey does not end there, further on, not far from Durlinsdorf, the GR532 suddenly leaves the Jacquaire path and ventures toward other horizons, leaving the pilgrim behind, along with their Camino Way. |

|

|

| Crossing the heart of the village, the route brushes past the Espace du Lavoir, a place once animated by the murmur of water and the familiar gestures of washerwomen. Today the basin is dry, deserted, frozen in a silence that tastes of nostalgia for a vanished time. Where water once sang between stones, only a trace remains, a ghostly imprint of what used to be, like a muffled echo of past days. This passage through the village centre feels like a suspended pause, a breath that invites meditation on how fleeting things are. |

|

|

|

|

| Soon after, the route begins to climb, following the steady, gentle slope of Rue des Orfèvres, where the village unfolds its old houses, witnesses to lives forged across the centuries. These buildings, their facades softened by time, where each stone seems to whisper an artisan’s secret, line up like guardians of the past, watching over the hiker as they make their way upward. This ascent is not only an effort of the body, it is a rise through time, a silent dialogue with those who shaped this place. |

|

|

| As Rue des Orfèvres slips beyond the village, it sinks into the forest’s deep hush, leaving behind the fading echo of human voices. Nature takes back its rights, and the path becomes an invitation to solitude. |

|

|

| The path now climbs more steeply, challenging the dense forest over a carpet of earth mixed with stones, small resistances under the walker’s soles. The slope grows steeper, rough, almost alive, like a call that urges you onward toward the promise of a summit. The Don Bosco colony, an oasis of humanity at the edge of the woods, soon appears on the horizon like a refuge in the heart of untamed nature, while the Rossberg Tower rises very far away, guardian of the panorama to come. |

|

|

| This track, wide and rustic, threads into a living theatre where beeches and oaks play the role of majestic pillars. The soft ground, steeped in woodland scents and fertile humus, stretches underfoot and invites a calm walk, almost meditative. |

|

|

| At the height of this effort, Rue des Orfèvres, whose name sounds almost ironic beside the wildness that holds it, meets the D432, a modest departmental road that loops around Ferrette like a discreet serpent. Here, nature yields gently to human infrastructure. |

|

|

| Near a modest parking area, almost insignificant in this rural landscape, most of the paths converge, like rivers flowing into a single estuary. All of them, or nearly all, lead toward Don Bosco, this haven of simple, functional architecture, a refuge and shelter for a colony tucked against the forest’s edge. |

|

|

| From the outskirts of the colony, the path climbs again, broad and firm like a forgotten avenue, in beaten ochre tones, winding into the forest’s thickness. It seems determined to lift the walker toward some invisible summit, through a procession of impassive trunks and suspended foliage. The ground, compacted by time and the quiet passage of walkers, takes on a texture that is soft yet stubborn. |

|

|

| A little higher, as breath shortens and thighs begin to burn, a solitary bench waits, set there like a promise of relief. Yet more than a rest for tired muscles, it is a strategic lookout. A signboard stands there, bristling with symbols like a modern palimpsest. Two tracks appear. One, marked with green dots, climbs straight toward the Rossberg’s crest. It invites and tempts, but it leads you away. The other, more discreet, clings to the faithful yellow rectangle, your thread of Ariadne, the GR532. Those wise enough to consult the map slipped into their pocket when leaving Ferrette will understand that the hour has not yet come for the final ascent. Still, the first hints of doubt already hang in the air. |

|

|

| Further on, the trees become true wooden totems, covered with marks, symbols, colours. You might think you are moving through an ancestral land, set with the invisible tribes of a forest that speaks a language of signs. Yet that language, multiplied too often, blurs its own message. The blue cross appears in its turn, silent and parallel, layering itself over the yellow rectangle and the pilgrim’s shell, sometimes washed out by rain, rubbed away by wind. What should you follow? Each colour becomes a word, but all of them overlap, sometimes cancel one another. The path turns into a confused dialogue between invisible tribes, the Apaches of the local itinerary, the Sioux of pilgrimage. |

|

|

| And yet the path continues, gaining altitude again, then turning after brushing past a water reservoir. There the ground changes, earth gives way to stone, and the path descends in a gentle slope, as if granting the walker a moment of grace. |

|

|

| All around, the majesty of the great beeches lends the route a quiet solemnity. Each step echoes beneath their vaults like in a Gothic nave, and suddenly a familiar flash catches the eye, the traditional red and white of the GR. An almost moving apparition. Since Basel, this sign had all but vanished, and seeing it again here, among so many others, sparks a surprisingly bright joy, almost childlike. Yet the bewilderment remains, why do these yellow rectangles coexist with the official waymarking. With so many paths crossing, logic dissolves. The walker no longer knows whether they are following an established line or a legend still being written. |

|

|

| Little by little, a reflex sets in. Your eyes no longer roam freely over the trees, or toward the play of shadow and light dancing among the branches. No. Your gaze becomes practical, almost feverish. It searches, inspects, hunts for the slightest mark, the faintest colour that will confirm you are on the right way. This is no longer a poetic wandering; it is vigilance at every moment. You sometimes forget the beauty of the undergrowth, the elegance of the trunks, the subtle scents of moss and leaves. All of it fades behind the urgency of not getting lost. Every missed sign becomes a threat, every junction a question. And in this forest, vast as an ancient memory, error is not a hypothesis, it is a constant risk. |

|

|

|

|

| After a few oscillations, the path opens onto a light-soaked clearing. A kind of breathing space in the dense forest, a bright escape after the weight of the undergrowth. It is there, in this opening, that the path marked with a blue cross leaves your route. It runs off to the right in a gentle curve toward Dr Herings’ cave, a place the attentive walker may keep for another ramble, more sideways, more meditative. |

|

|

But for you, there is no question of yielding to the call of hollows and detours. The route you are following continues straight ahead, faithful and spare, carried by the logic of the yellow rectangle that guides your steps like a line of destiny.

| For a moment the path skirts the clearing and keeps it in sight, then slides toward a patch where the wood has been cut recently. Felled trunks lie there in heaps, like toppled giants, exiled from their verticality. |

|

|

|

|

Soon a sign appears, planted at a crucial intersection. This is where everything is decided, where you must keep your eye sharp and your mind clear. Two routes run in parallel, two arrows point the same way, and yet one will lose you while the other will guide you. To the left, the path toward Vieux-Ferrette, wide, inviting, almost too beautiful to be honest. To the right, narrower and humbler, the one you must choose. The trap is subtle, all the more so because the signage becomes talkative, confused, splashed with triangles and multi-coloured rectangles, as if every marker-setter had wanted to tell their truth without consulting the others. The sign itself is badly placed, shifted, sowing a fatal doubt. In this proliferation of clues, you realize how much orientation here becomes a mental ordeal. You must not take the direction of Vieux-Ferrette. The true itinerary, that of the GR532, that of Santiago, snakes discreetly to the right. It would have been enough to place the sign ten meters further on. But no. You have to earn your path.

A simple reading of this forest’s layout, complex as an old tapestry, makes it clear that neither Vieux-Ferrette nor Bendorf are the right choices. They are ways off the road, paths without a guiding star.

| Fortunately, as soon as you take the right path, the more discreet one, the markers return. The yellow rectangle reappears, reassuring and faithful, soon joined by the red and white bicolour rectangle, the GR sign. Relief, a confirmation. Yet curiously, the Compostela shell, that universal sign that comforts solitary walkers, is still nowhere to be seen. Like a silence in a sentence you wanted to hear carried all the way to the end. |

|

|

| It is at the “Hêtre de la Vierge” that you breathe again. This old wooden colossus, rooted in the earth like an altar, announces an important moment, the junction, a crossing where paths clearly diverge. |

|

|

| To the left, the path goes down toward Bendorf. But the straight way, the one that leads to La Saboterie, remains the most logical and the safest. It is also the one recommended by the Friends of the Camino de Compostela, continue to the Buergerwald pass, then drop toward La Sabotière, staying faithful to the GR532. Bendorf, despite its charming name, is not the right choice. Too rural, too out of the way, it forces you into a wide manoeuvre when leaving the village to recover the sacred thread of pilgrimage. Better to avoid it.. |

|

|

| The path then becomes harsher, rockier. It climbs into the woods with determination, as if it wanted to test the walker’s will one last time. The slope asserts itself; breathing grows heavier. The ground, mixed with stones and hard-packed earth, becomes less forgiving, more firm. Each step is a negotiation with fatigue, but the direction is clear. |

|

|

|

|

| At the end of a sustained climb, steep and relentless, the forest opens onto something like a green balcony, a threshold where the walker, out of breath, discovers a true mosaic of signs. Here again the trees act as standards, yellow rectangles, red and white bands, arrows, triangles, everything is there like a disorderly parade. Then a green and white band appears, unknown until now, arriving like an uninvited guest. For whom, for what. A mystery. It feels like a scavenger hunt where each organizer left their own language without consulting the others. Too many arrows, too many instructions, too many colours, the eye saturates and the mind hesitates. As in a war council among tribes, each tree becomes a painted warrior, each trail a possible trap. |

|

|

| Yet at this precise spot, despite the excess of waymarking, error is impossible. All paths, like tributary streams, converge into one and the same bed, an obvious, unique descent that plunges back into the heart of the forest. Choice dissolves, and the path takes over again. It becomes single, clear, docile. |

|

|

| A few dozen meters lower, a surprise, the path crosses an old boundary marker, standing there like a forgotten remnant. It is upright, proud, engraved with ancient signs, and its presence is startling. What boundary? You are far from Switzerland, still well to the north. It evokes a time when lands were more fragmented, when forests served as lines of division. Here, it is above all poetic, a mute witness to an administrative past now erased by leaves. |

|

|

| A little further on, the descent continues, but the trail narrows, as if it wanted to become more intimate, more discreet. It winds under the protection of immense beeches whose pale, smooth trunks rise straight toward the sky. Their silence is deep, almost sacred. |

|

|

| Lower still, the slope softens, legs loosen, breathing calms. The landscape changes, the great trees yield their dominance to lower, more tangled vegetation, bushes, shrubs, a few hazels. The air feels more open, light filters more frankly. It is a gentle transition, an interlude between two forces, the majesty of the beeches and the finer presence of humbler species. |

|

|

| But this breathing space does not last. The beeches return, powerful, anchored like ancient pillars. A few oaks, rare but present, recall their quiet authority. The conifers grow timid, almost absent, in this leafy symphony. |

|

|

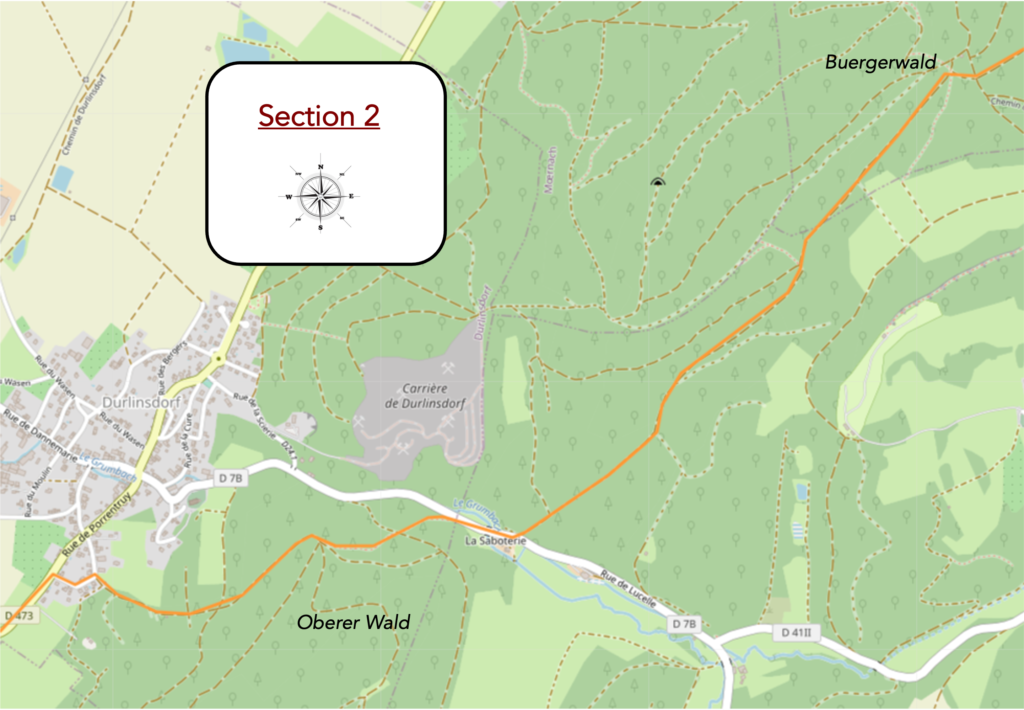

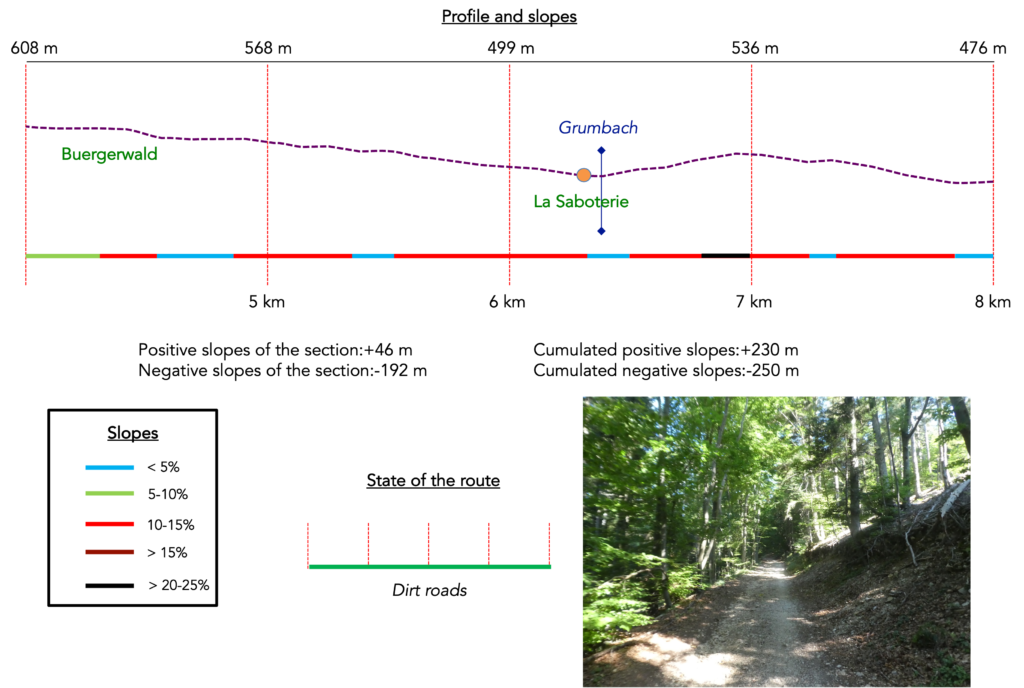

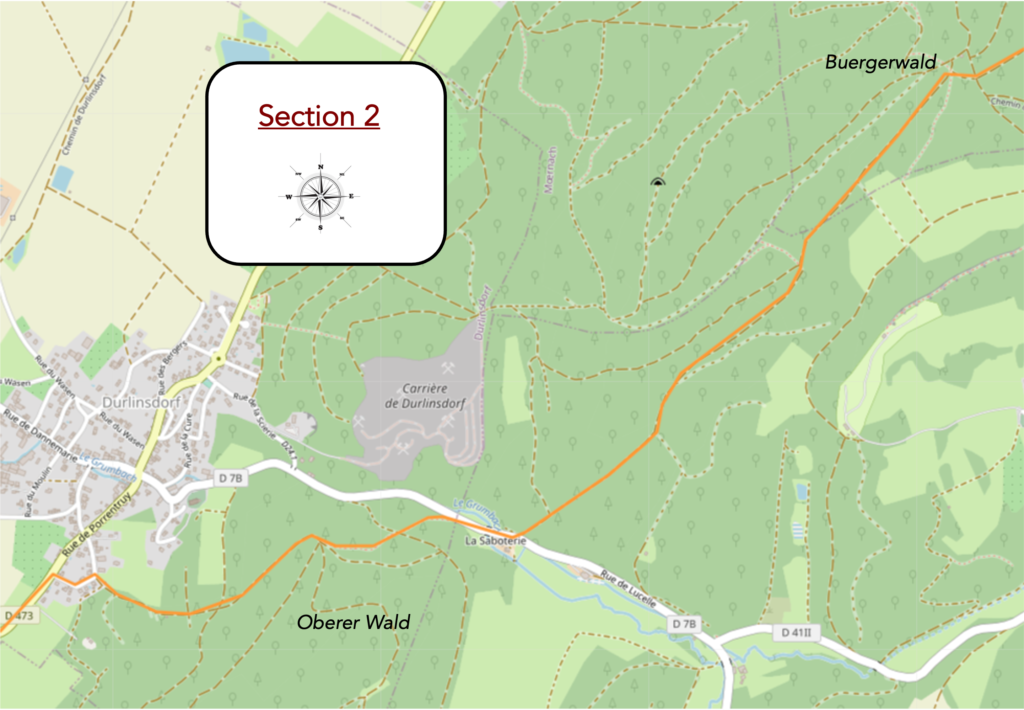

Section 2: You are not out of the woods yet

Overview of the route’s challenges: marked slopes, though mostly downhill.

| The path soon opens onto the place called Buergerwald, a kind of wooded hollow where the world seems to slow down. There, tucked along the edge, a log cabin stands in silence. It looks like one of those forgotten shelters from old tales, nestled against the flank of the woods, as if trying to vanish into the very bark of the trees. Moss is already climbing over its stones, and the wood has darkened under past rains. It seems to be waiting for you. |

|

|

From this peaceful shelter, La Saboterie is only two kilometres away. A wide forest dirt road leads there, thick, firm, clearly laid out, it descends with confidence, as if it knows exactly where it is going.

| The descent is pleasant. Your steps lengthen and the rhythm loosens. In places, though, the slope rears up and tightens for a moment, reminding the walker that nothing is ever given entirely without effort. Still, the whole remains fluid, punctuated by clearings and green breathing spaces. |

|

|

| Then, suddenly, another path appears, coming from Bendorf. It merges here with your road and displays the same eternal red and white GR markings. Another one, one more, and doubt begins to dance again. What logic governs this profusion? Who is telling the truth? Every crossing becomes a riddle, every marker a possible answer, never guaranteed. The itinerary sometimes seems designed to lose everyone, pilgrims, strollers, the curious alike. |

|

|

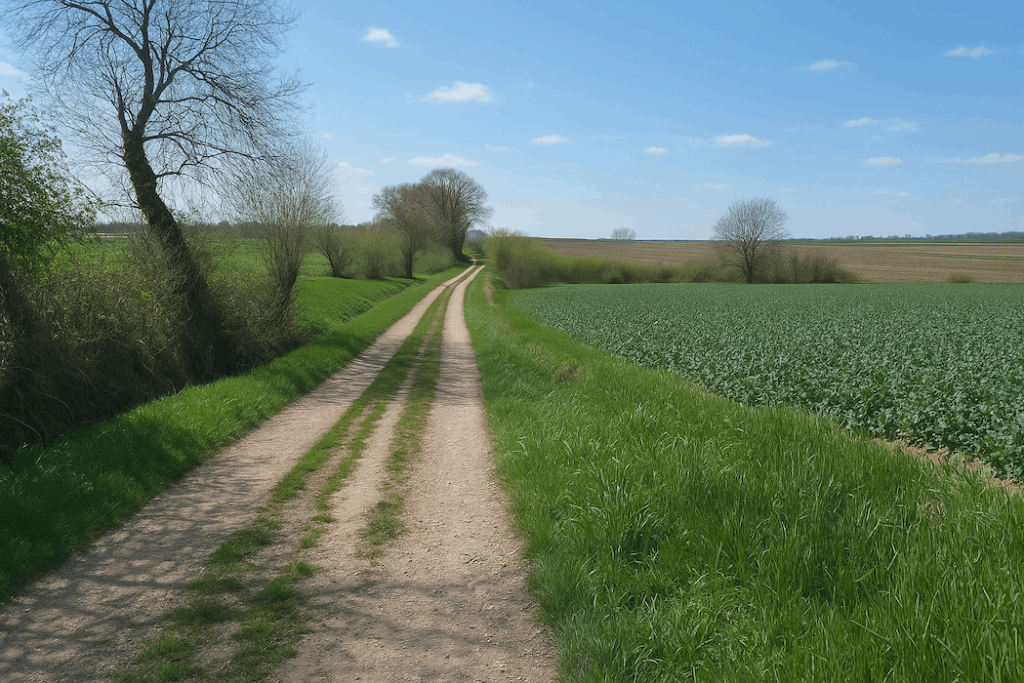

| The path now becomes a long straight line, perfectly direct and gently sloping. It cuts through the forest like a slow incision, without a single detour, without surprise, as if the earth itself had resigned to guiding the walker to the next halt. |

|

|

| At the bottom of this calm but persistent descent, the path meets the small departmental road D7b, at the place called La Saboterie. An old sawmill sleeps there, abandoned, rustic, worn out. The very name, Saboterie, sounds like a promise of craft and shaped wood. Yet no one saws anything there anymore. The workshop has fallen silent. And you, finally coming out of the forest, feel you have crossed a long, winding riddle, a gentle ambush, set not out of malice but out of excessive zeal. |

|

|

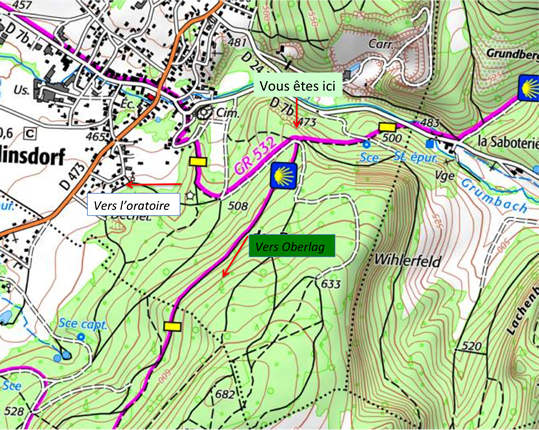

| But do not celebrate too quickly, because here as well the route becomes complicated again, not by its topography, but by the tortuous logic of its directions. There is only one route, the GR532, and therefore, officially, the pilgrimage route toward Compostela as well. Listen to what the local Friends of the Camino publish, in an excess of cryptic enthusiasm, “Follow the road to the right for 200 meters, then leave it on the left, yellow rectangles, for an uphill trail. Reach a wide forest track and take it to the left, do not follow the waymarking, really. At the first junction, go right onto a slightly narrower uphill track. At the top of the climb, find the yellow rectangle waymarking of the GR532 again and follow it downhill to reach a junction of four tracks.” A riddle inside the riddle, a syntactic labyrinth. Who wrote that? Not a walker. A poet of the absurd, perhaps. Why not simply scatter small white pebbles, as in fairy tales? At least that would have reassured lost children. As described, the route first has you follow the road for two hundred meters after crossing the Grumbach, a small discreet stream that murmurs underfoot, almost shy. Asphalt replaces dead leaves, but it is only a transition. The real path, the one that seeks height, is still hiding to the left, somewhere higher, in a fold of the forest. |

|

|

| As announced in the Friends’ sibylline recommendations, a steep trail bristling with stones launches into the undergrowth. It climbs with determination through dense branches, carving the slope like a mule track, the ground ringing under your soles. |

|

|

| Be reassured, this time the yellow GR532 marker does not leave you for a step. It is there, firmly painted on the trunks, like vows of fidelity renewed at every bend. Yet, as if to shuffle the deck once again, the white and green marks seen earlier also appear, remnants of another network, another logic that only the forest still seems to understand. Below, beyond the high stands of trees, a metallic roar rises, the jackhammers of the Dürlinsdorf quarry batter the rock with the fury of a mechanical storm. The racket swells. |

|

|

| The trail, growing narrower, then crosses a logged area. The great silhouettes of beeches have given way here to frail regrowth and unruly thickets. It is a landscape in recovery, where the forest is dressing its wounds and preparing its slow rebirth. |

|

|

| And then the slope stiffens. The last rise is almost unfairly steep, like a final test thrown at the pilgrim. You climb in silence, short of breath, muscles taut. |

|

|

| Then, without warning, the path opens again. A light-filled clearing welcomes you, wide, peaceful, almost solemn. Several directions sketch themselves out like competing hypotheses. The GR532, marked with both the yellow rectangle and the Compostela shell, points toward Durlinsdorf. Another, toward Oberlag Lucelle, also bears the yellow rectangle. And that is where things go wrong, two paths, two opposite directions, one single marking. A cartographic prank, or a subtle test of discernment. In any case, inattentive walkers can go astray here, with no easy return. |

|

|

Fortunately, you are whispered the only thing to remember, follow the yellow rectangle of the GR532 toward Durlinsdorf. It will soon guide you to a small oratory tucked into the folds of the hills.

| From the junction, the path descends. It is a vigorous but flowing slope, inside a deciduous wood where a few spruces pierce through, slender and dark, like solitary sentinels. |

|

|

| The ground turns stony and your steps must adjust. The path runs to a crucial intersection. Here, the GR532 continues alone, while the Compostela shell, with an almost melancholic discretion, goes off to follow its own destiny. The two ways split, each toward a different horizon. It is the silent farewell of two traveling companions. |

|

|

| The forest thins. The oratory is there, discreet, above Durlinsdorf. You reach it almost by surprise. It rises into the landscape like a peaceful thought, white and collected, watching over the valley. |

|

|

| One must salute the intention of those who design routes. Keeping walkers off asphalt is a noble goal. Still, the signage must follow. Here, intention dissolves into excess. Too many indications kill indication. It also helps to understand that pilgrims are rare in this sector, apart from a few hikers coming from German speaking Switzerland, Germany, or farther east. The locals, for their part, move through these trails the way one crosses a garden, without hesitation. For everyone else, if confusion reigns at La Saboterie, it is better to go carefully down the road to Dürlinsdorf. You will only miss the oratory, which you can in any case reach above the road that links Dürlinsdorf to Liebsdorf. The Camino path here only brushes past Durlinsdorf, where the GR652 also passes.

The oratory, recently renovated, is a modest but moving chapel dedicated to Our Lady of the Sacred Heart. It keeps watch in silence, motionless in the wind, sheltered by the hills like a pearl in its shell. |

|

|

| From here, the route becomes more readable, almost obvious. It simply follows the road, like a faithful dog trotting at your side. The route glides gently toward the village of Liebsdorf. |

|

|

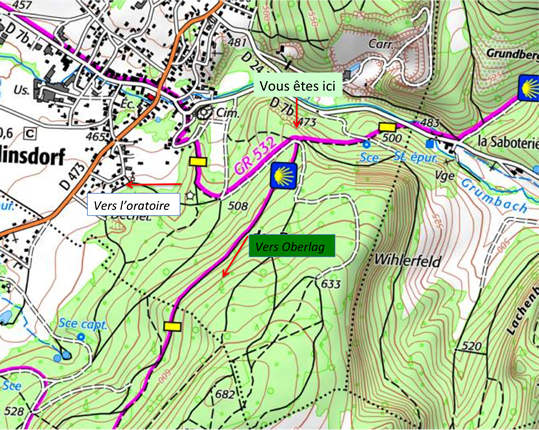

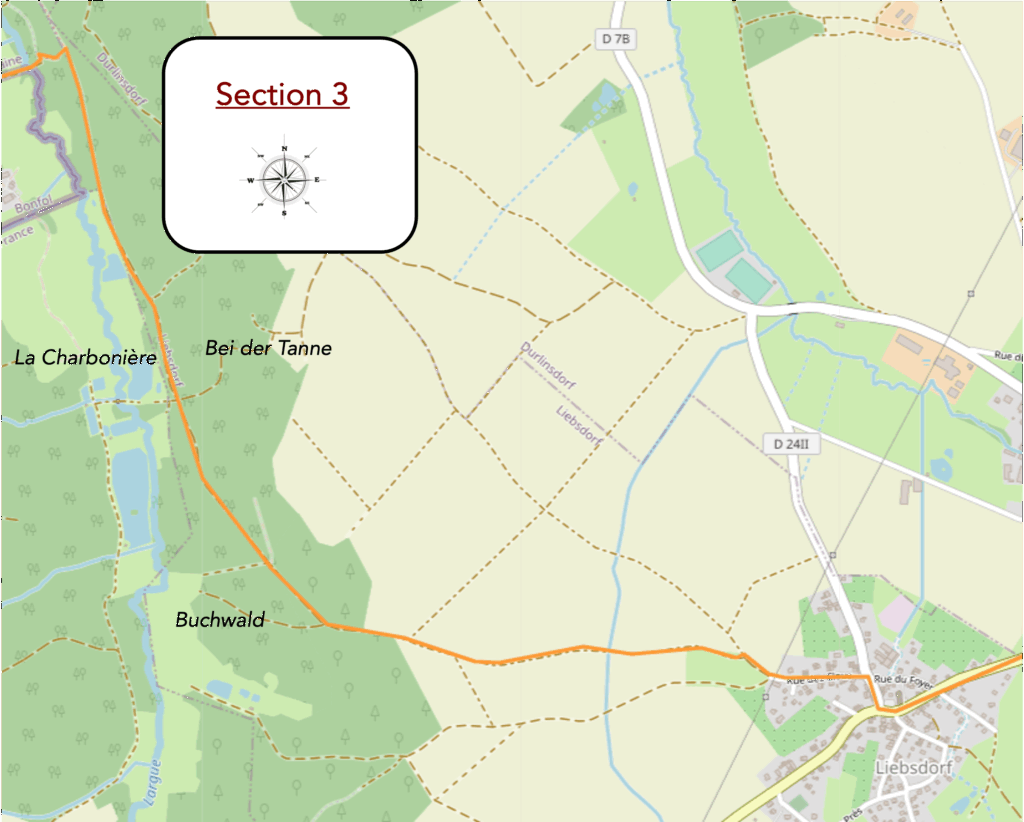

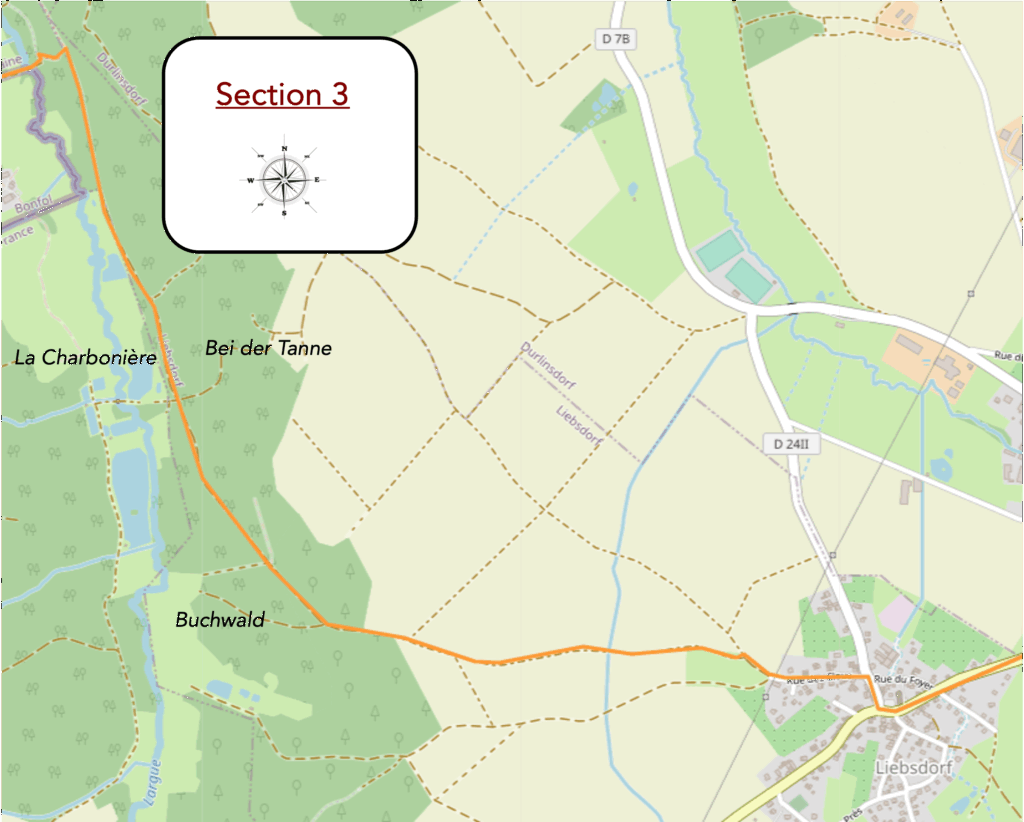

Section 3: From France to Switzerland

Overview of the route’s challenges: a route with no difficulty.

| The route finally reaches Liebsdorf, a village near Durlinsdorf, nestled in a valley where time seems to have stopped. Here, conversations drift from open windows in an ancestral dialect, Alsatian, a language both soft and guttural, clinging to the earth the way dawn fog clings to the hills. This living speech, passed down from generation to generation, is a resonant vestige of local history, a golden thread binding the inhabitants to their roots. |

|

|

| The road then slips into the heart of the village, winding between houses as colourful as an Impressionist palette, passing the church, plain and motionless, a silent guardian of souls and centuries. |

|

|

| In these villages, the walker discovers houses with bright façades dressed in ochre, pink, or pastel blue, and above all those famous half-timbered homes, their exposed wooden frames drawing diamonds and crosses like the lines of an old parchment. This typically Alsatian style of building has crossed oceans, and can now be found in the United States, transplanted like a cutting of European architecture. In the past, the walls were filled with wattle and daub, a humble mix of mud and straw, now replaced by modern mortar. Yet the soul remains unchanged. |

|

|

| The route catches its breath as it leaves the village, along the poetic Rue des Clous, a name that rings like a workshop memory. Here it is the red and white waymarking of the GRE5, the great European long-distance trail that winds across the continent for more than 3,000 km, from Pointe du Raz to Verona. It is a monumental path; a red thread stitched into the map of Europe. You, modest walkers, will follow only a fragment of it, yet every step will carry the imprint of that great crossing. |

|

|

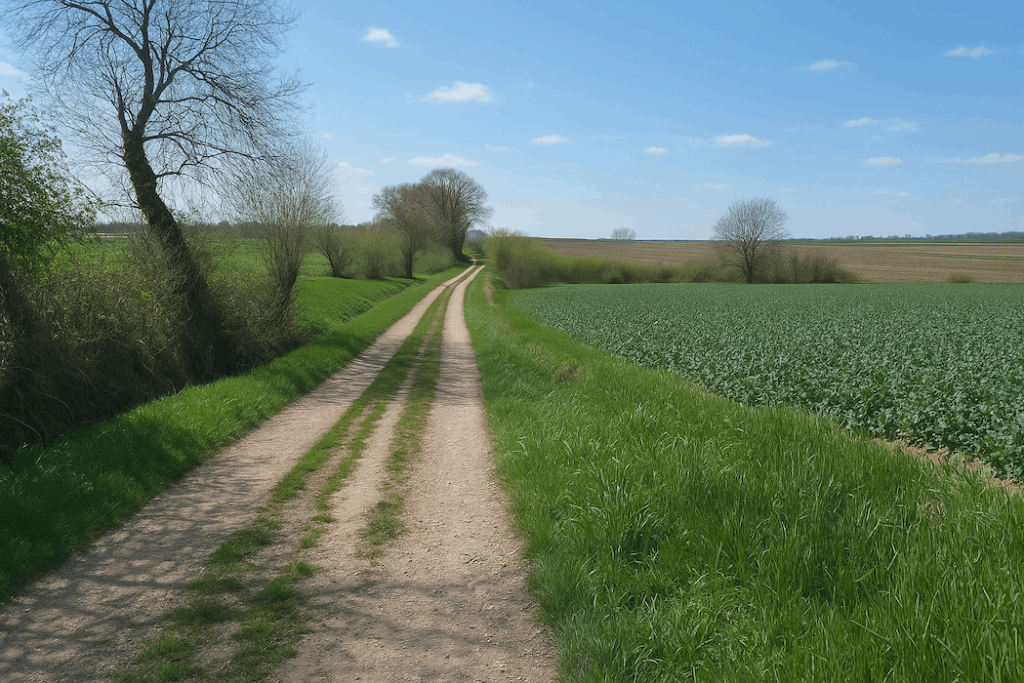

| The dirt road leaves the last wall behind and melts into the countryside. The broad track stretches like a ribbon toward the horizon. Fields reclaim their place. Vast expanses of maize rustle in the wind, raising their green ranks like a promise of abundance. After the dense shade of the forests, this return to rural light feels like a deep breath. |

|

|

| Here, a few observation posts punctuate the edges of the woods. They are no longer manned by wartime lookouts, but by hunters, passionate and sometimes cruel, watching for the wood pigeon, a migratory bird whose flight skims the treetops. |

|

|

The dirt road undulates gently, running alongside a hedge that seems to race beside you like an old companion. You are walking on a GR, the red and white markers, occasional and reassuring, set the pace of the march. Yet there is one extra detail here, a small square, a nod to the prestige of a European trail. You feel like a traveller in a unified world, a pilgrim of a continent. The path then aims for a singular place, “kilometre zero”, the symbolic starting point of a story shattered by the First World War. It is a mute boundary stone, heavy with memory.

| Farther on, the stony track softens as it enters the deciduous forest of Bei der Tanne. Cool shade welcomes the walker with a vegetal tenderness. The trunks, straight as ancient columns, filter the light into moving lace. It is a return to the intimacy of the undergrowth, to the discreet crackle of dead leaves, to the enveloping peace of trees. |

|

|

| In the calm thickness of this forest, beech reigns supreme. Its pale, smooth trunk, rising like a cathedral pillar, gives the undergrowth the air of natural architecture. It is worked here without respite, yet always with respect, so deeply has it shaped the landscape for centuries. Soon, the path brushes the first ponds, countless in this region. The silence that hangs over them, broken only by the distant cry of a heron or the tremor of a fish at the surface, lends these places an air of secrecy. It is easy to imagine phantom figures from the Resistance, sheltering in the foliage or slipping into shadow at dusk,

The walk continues alongside a chain of ponds linked by the river Largue, a thin water snake that has carried far more than reflections. This was a strategic place where French and Swiss forces watched the German line. The atmosphere thickens with memory and tension. You are nearing the place called La Charbonnière, a name that seems to exhale the smell of fire, smoke, and secret vigils deep in the woods. |

|

|

| On the other side of the Largue, hidden behind a row of beeches as straight and rigid as soldiers frozen in waiting, you can make out the sturdy silhouette of the Largin farm. The scenery shifts in tone and grows more rugged, as if the ground itself remembered troop movements and border tensions. A trail climbs slightly, cutting its line between roots. It crosses a severe granite boundary marker, stamped with the number 109, the first in a long series of silent witnesses. These stones, relics from the time when Switzerland drew its limits with scrupulous care, now haunt the imagination of another conflict. |

|

|

| Little by little, the trail takes on the feel of a war set. The terrain becomes chaotic, perfect for ambushes. Everything here evokes trench warfare, the hollows in the ground, the cover of branches, the heights ideal for hidden fire. Every corner seems to murmur stories of waiting, of watching, of hope suspended on the sound of a footstep. |

|

|

| The “Km Zéro Circuit”, that is the name of this history laden trail, is a French Swiss initiative born from the centenary of the Great War. Volunteers put their hands in the mud, cleared blockhouses swallowed by vegetation, restored concrete works the years were trying to erase. Along these 7.5 km, which we will follow only in part, twenty military positions, German, French, and Swiss, come back to life through panels, silhouettes, and names. Yet most of them fade, swallowed by oblivion, like a soldier’s footprints in melting snow.

The path then crosses what was the first German defensive position of the front. From this precise point, the German line ran for more than 750 kilometres, a barbed thread stretching from the Swiss border to the grey beaches of the North Sea. A backbone of fortifications, trenches, and pain. |

|

|

All of this has its roots in an old wound, France’s defeat in 1870. That bitter reverse had granted Germany part of Alsace and Lorraine, lost provinces, torn away until the end of the First World War in 1918. In 1914, at the start of hostilities, the German front followed the left bank of the Largue. On the opposite bank, French forces kept watch, and a little farther south the Swiss observed from the vicinity of the Largin farm.

And yet, despite this burning proximity, despite the tension running through the veins of forests and rivers, no major battle broke out here. This front was a frozen front, a silent line, a territory of surveillance and restraint, as if the forest itself had whispered peace to those who stood within it.

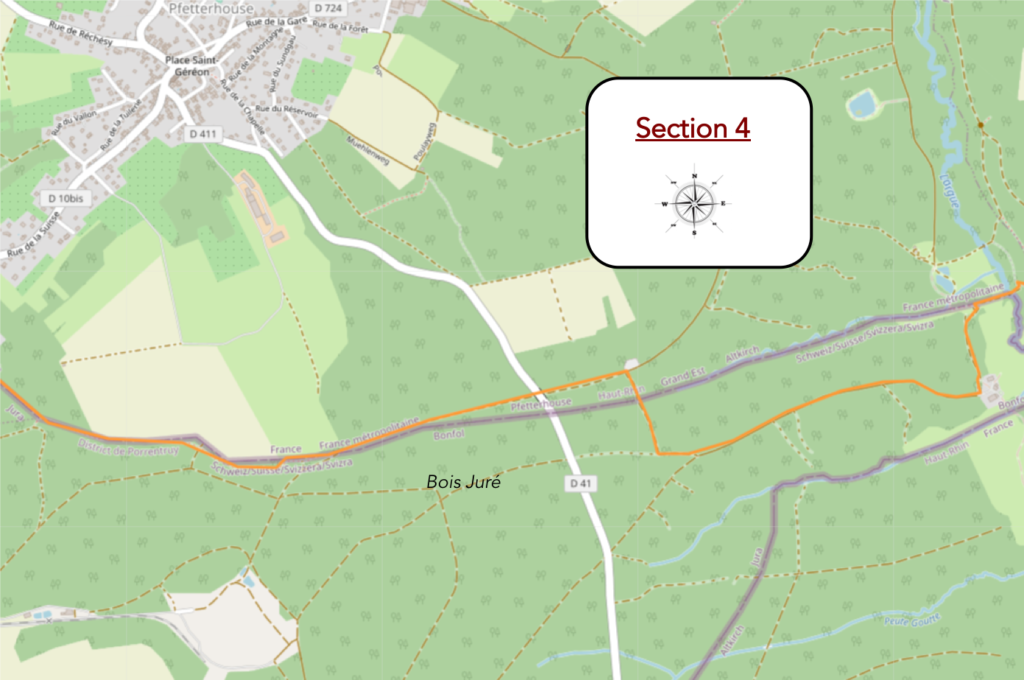

Section 4: Between France, Germany, and Switzerland, between war and peace

Overview of the route’s challenges: constant undulations, but no real difficulty.

| At the time, Switzerland, neutral yet on alert, occupied the strategic position of Largin. For its soldiers, this place became a symbol, almost a sanctuary. Using whatever materials were available, wood, stone, corrugated metal sheets, they built rudimentary field structures. None of this remains today. Only gnarled roots, hollows in the ground, and silence still bear the imprint of these temporary installations. For a long time, the terrain remained waterlogged and difficult to access, swallowed by unruly vegetation. But in 2012, the Swiss municipality of Bonfol decided to restore the site. Military engineers were called in. The area was drained, and a footbridge was built over the Largue. Thanks to these efforts, the site became accessible once again, even if nature has kept a certain rawness. |

|

|

But in truth, could this stream really have slowed the German army? This thin ribbon of water, discreet and almost timid, hardly seemed a serious obstacle. And yet, on this border, every detail took on symbolic weight.

| The path then reaches boundary marker 111, austere and immovable. Beside it, an old Swiss observation post still stands, frozen in its purpose. It is a modest remnant, yet charged with intensity, a witness to active neutrality and silent vigilance.

In 1914, the French authorities decided to fix the starting point of the Western Front here, at boundary marker 111. This is Kilometre Zero, the point of origin of an immense and tentacular front that would mark European history forever. Along this stretch of border, the Swiss army deployed its own resources, guard posts, observation towers, sentry boxes. The northern Largin post, facing the boundary marker, was a small blockhouse of wood and earth. In 2012, it was rebuilt by Swiss military engineers. It was a gesture of remembrance, almost an act of symbolic reparation. Switzerland too wished to inscribe itself in this European memory. A country not wounded by war, it sought to recall that its soldiers also kept watch, observed, and protected, preserving peace where others lost it. |

|

|

| Before you now stretches the Largin farm. It rises from the clearing like a mirage. Around it, cows ruminate peacefully, indifferent to the stories of war. The Largue, a calm stream, winds at its feet, sheltering plump carp that sometimes make the pride of nearby restaurants. Once drowned in marshland and erased by time, the farm has been largely rebuilt. It has come back from far away, like a revived memory. |

|

|

| A wide packed dirt road leaves the farm. You are still walking on the GRE5, which here coincides with the Kilometre Zero circuit. The path enters the woods once more, beneath tall beeches with trunks so straight they seem drawn with a ruler. They stand like a silent orchestra, aligned by time. |

|

|

| Farther on, the forest changes. It becomes more varied. Spruces appear, dark and pointed, accompanied by dense undergrowth. The landscape grows thicker and more secret, as if the forest wished to conceal a few more forgotten pages of history. |

|

|

Then the road emerges onto a parking area. This is the secondary entrance to the circuit, more developed and more modern. But your route continues toward Pfetterhouse. Still on the GRE5, you follow this red thread between past and nature.

| From the parking area, a narrower path dives once more beneath the foliage. Here, certainty fades. Are you in France or in Switzerland? The border is invisible, dissolved into the landscape. Only the Swiss granite boundary stones, placed at regular intervals, draw a discreet line between the two countries. From time to time, an old customs sign appears between two trunks. That is all that remains of the passage between two states. Rest assured, you will never be stopped here. The forest is free territory, |

|

|

|

|

| The path then reaches the edge of an old railway line. Beneath the grass and gravel, the straight traces of a forgotten past are still visible. It was a narrow-gauge line, built mainly for military use, linking Pfetterhouse on the French side to Bonfol on the Swiss side. An iron link between two worlds on alert. It would be illusory to hope that this line might one day feature in the railway revival projects so often announced in France, those same projects that have promised wonders for more than half a century, while rails rust away in the silence of abandoned countryside. |

|

|

| The GRE5 then follows this former railway line, its sleepers gone, replaced by tall grass and the shadows of trees. It passes beneath the D41, a modest departmental road linking Pfetterhouse to Bonfol. The concrete of the bridge above cuts through the gentleness of the place, like a slightly brutal reminder of modernity. |

|

|

| The route continues for a few more metres along the old railway alignment, before turning onto a narrower path. Here, the border is once again marked by a stone, number 129. It rises from the ground, sober and silent, like a punctuation mark of stone in the long sentence of this border landscape. |

|

|

| The small forest trail then bounds between the trunks, almost cheerful in the way it undulates. It crosses a quiet clearing and steps over a shy, unnamed stream, one that seems drawn for children or for fairy tales. The forest known here as Bannholz is magnificent, especially beneath the canopies of great beeches and venerable oaks. The ground is soft, almost carpeted, and light filters through in shifting patches, as if projected by a living-stained glass window. |

|

|

| A little farther on, the forest opens. The air becomes sharper, the light more direct. The path leaves the heart of the woods to run along its edge, like a walker hesitating to return fully to the light while not yet leaving the shade. |

|

|

| Soon after, boundary stones signal the Swiss municipalities of Bonfol and Beurnevésin. They appear discreetly, like administrative reminders slipped into a pastoral setting. These names set into the earth tell a story of belonging, territory, and peace regained. |

|

|

| Farther on, the path, faithful to its meanders, continues to wind a little through the woods until it emerges onto a sports field at the entrance to Pfetterhouse. The contrast is striking. After so much silence, memory, and forest, here are the white lines of a playing field. As if, after walking along the edge of ghosts, modern life had come to greet the walker. |

|

|

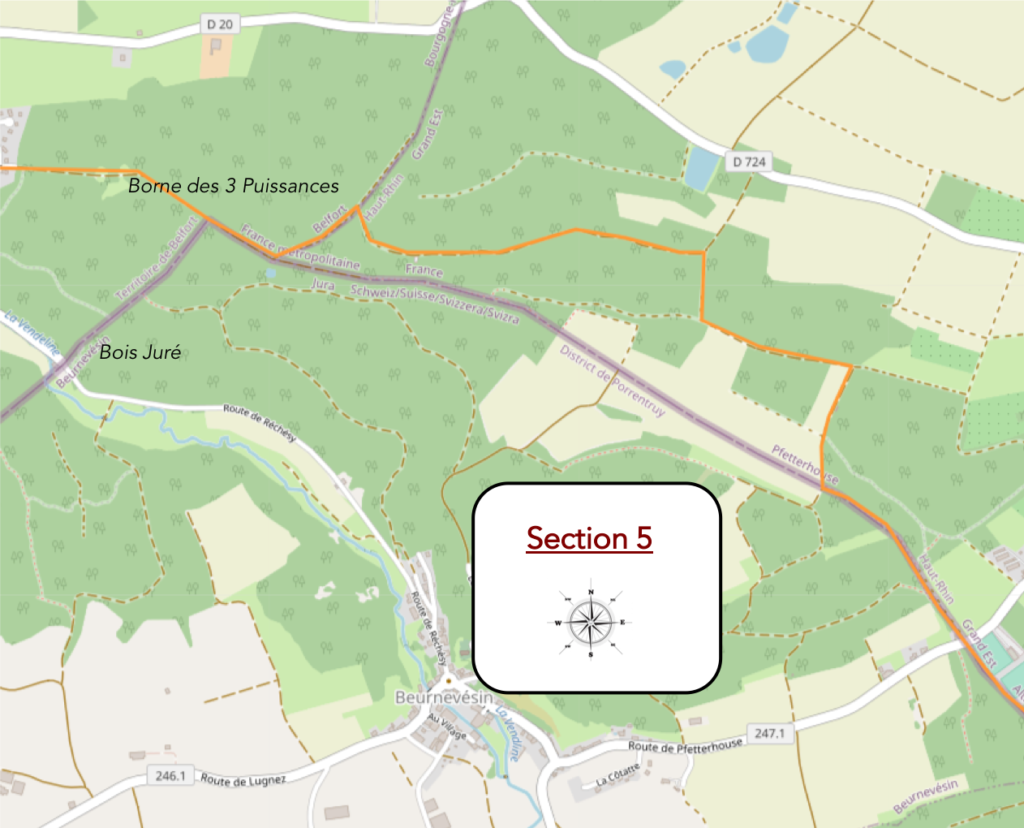

Section 5: Gradually leaving war behind, returning to France

Overview of the route’s challenges: a few gentle slopes before a steep descent toward Réchésy.

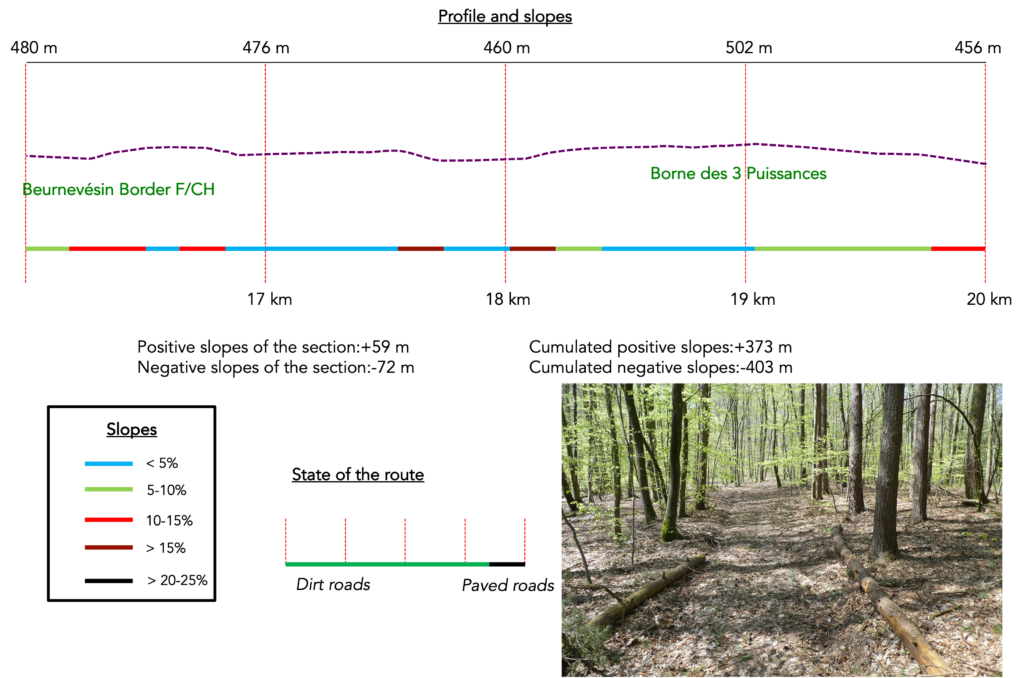

| The route, characteristically discreet, does not lead into Pfetterhouse. Instead, it slips away toward the Swiss customs post of Beurnevésin, a small crossing point without excessive ceremony, yet filled with the calm of a borderland. Here, the direction is clear: head toward the “Three Powers Boundary Stone.” The route initially remains on the GRE5, following the border like a tightrope walker balanced between history and nature. |

|

|

| A path enters the forest once more, and its line begins to hesitate gently. It sways, winds, skirts the trees, and follows the soft contours of the land. One might think it is hesitating, reflecting at each step, and the walk becomes contemplation. |

|

|

Most of the time, the path is wide and almost soothing beneath the tall beeches. Their straight trunks and dense foliage form a natural vault above the walkers’ heads. One feels protected there, welcomed into a vegetal nave where each step sounds softly on the carpet of fallen leaves.

| As you approach the “Three Powers Boundary Stone,” the relief softens and the hill becomes almost flat. The horizon opens up. No map is needed here. The signposts are numerous, clear, and reassuring, indicating the remaining distances. They seem to say, keep going, you are nearing a singular place. |

|

|

| And the route, still faithful to the GRE5 markings, reaches, after a long ascent, the “Three Powers Boundary Stone.” It is a point of convergence that is both modest and solemn. Nothing imposing, yet a place heavy with meaning. |

|

|

In 1870, the Franco Prussian War ended with a bitter peace treaty, and France lost Alsace and Lorraine. Borders were redrawn, and it was here that a boundary stone was set, the famous “Three Powers Boundary Stone,” marking the geographical meeting point of France, Germany, and Switzerland. On this pentagonal stone are carved the initials of each country. For nearly half a century, this place became a destination for outings, a symbolic point of a reshaped Europe. But during the Great War, the border became a front, and the calm of the stone was overwhelmed by the crash of weapons.

| Today, the solemnity has faded. The place is no longer truly a patriotic destination. It has become a simple leisure area, where families stop for a barbecue or a picnic. In front of a small pond, a little green and slightly stagnant, memory dissolves beneath laughter and the smell of grilling food. |

|

|

| From the boundary stone, the path descends back toward the forest. Here you stand at the crossing of several routes, and the signs make this abundantly clear: the Swiss route, the GRE5, and even the mythical Camino de Santiago, marked by the yellow shell. It is a beautiful layering of stories and destinies, each following its own line, yet converging here for a moment. |

|

|

| Descending further, the path passes an unexpected monument: a large antenna rising like a useless tower, accompanied by an ironic inscription, a monument dedicated to the stupidity of human communication. Just after it, a water reservoir, sober and functional, brings this brief moment of contemporary satire to a close. |

|

|

| Finally, at the edge of the woods, a steep road runs down toward Réchésy. Here, you step onto a new territory, the Territoire de Belfort. Alsace is now behind you. Yet nothing truly disappears. Every step still carries the imprint of what the land has seen, preserved, and endured. |

|

|

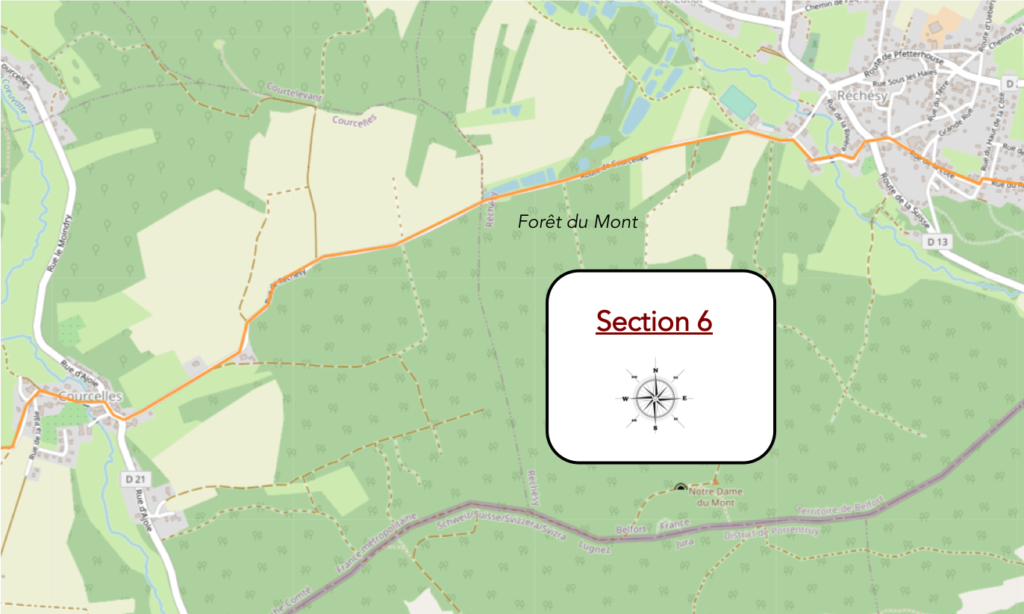

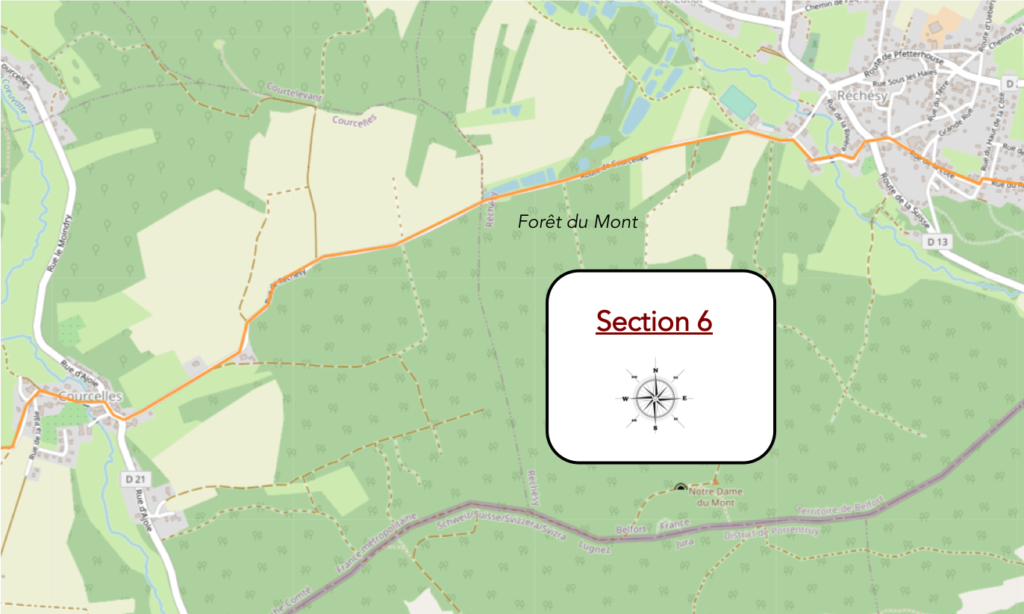

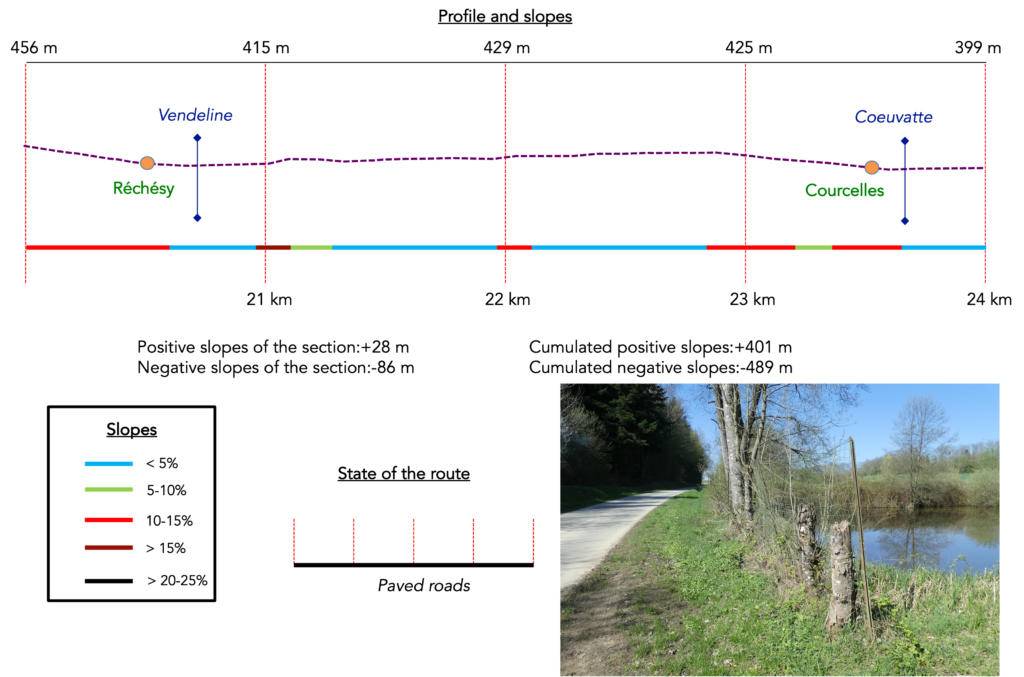

Section 6: From one village to the next

Overview of the route’s challenges: a steep descent toward Réchésy, followed by an easy route.

| The road plunges through the village like a slate serpent sliding down a steep slope, carrying the memories of centuries along its bends. It seems to have carved its furrow into the very flesh of the landscape, descending solemnly between the tight walls of old houses. With every step, the walker feels the gradient beneath their soles. One descends here as one would turn the pages of an ancient book, one after another, slowly, allowing time to lay its veil of silence on each stone. |

|

|

| The GRE5, the marked route followed until now, comes to an end here, gently fading into the tremor of asphalt. It crosses the D13 departmental road, where splendid Alsatian houses stand aligned, dignified and solid. These buildings, proud like matrons in festive dress, display exposed beams and half-timbered façades, guardians of a heritage rooted in land and time. Their simple, almost rustic elegance bears witness to the soul of a region, set in place with the precision of an illuminator. |

|

|

| At the edge of the village, like a threshold between two worlds, a stream steps in the way: the Vendeline. It flows wide and low, carrying lively, stubborn water that rolls over pebbles like an ancient voice. It is not yet a river, but it refuses to be ignored. It slips beneath the road and glides through tall grasses. |

|

|

Near the community hall, a wide gravelled area welcomes walkers, the hesitant, and those exiled by signage that has become too unclear. A forest of signposts rises here, each more enigmatic than the last, defying any cartographic logic. This is where the GRE5 leaves us, turning its back on France to slip away toward Italy, like a weary pilgrim following another journey. In return, the walk takes on a more local flavour. The markings change, new green rectangles replacing the old signs, like a change of alphabet within the same language. And suddenly, the scallop shell of Saint James, bright yellow against a blue background, appears with a clarity that borders on irony. Why does such clarity arrive so late, just when the route becomes simple? In the background, the remnants of Swiss markings linger, like the final notes of a song from elsewhere.

| But here, all the signs in the world matter little. One only has to follow, obediently, the black and smooth line of the D21 departmental road. This road leads to Courcelles, skimming the deep shadows of the Mont forest. The asphalt stretches like a straight promise, without detour, between the discreet songs of the trees. It demands neither choice nor interpretation. It is there, sovereign, carving its way like a beating vein through the body of the land. |

|

|

| The forest opens here into a vegetal architecture of rare nobility. The oaks rise straight as Gothic pillars, far from the stunted silhouettes seen elsewhere. They are sessile oaks, or perhaps pedunculate ones, spreading their leafy arms in a calm, sovereign gesture. Yet it is the beech that truly reigns here. It grows by the hundreds, its smooth, pale trunks standing like stelae, then sometimes lying piled along the roadside, ready to become warmth or furniture. It is called foyard, sometimes fayard, depending on the valleys, as if its very name carried a hint of melancholy.

Once, ash trees also thrived here, cousins of the beech, just as lofty. Some reached forty metres in height, a metre in width, and lived for centuries. But that time seems to have passed. A forester met at the forest edge speaks of their near total disappearance in the region. The scourge came from afar, from a forest in north eastern Poland in 1992. Chalara fraxinea, that clinical and chilling name, strikes ash trees with an incurable disease, ash dieback. A brutal drying that rises from the ground, kills the sap, closes the leaves. Experts are clear, the tree has little chance. Soon, only memory will remain. Another species Europe may lose, after the elms. And always the same helplessness, there is no remedy. |

|

|

| A few steps further on, the road brushes past the Grille ponds, two twin mirrors edged with reeds, frozen in crystalline silence. In this region, bodies of water appear in the landscape like mushrooms after rain, ubiquitous, modest, and mysterious. Yet these ponds owe nothing to chance. They are the result of the meticulous work of Cistercian monks, who from within their silence shaped the land so that it might feed both soul and body. In these still waters, they raised carp, the fish of penance, discreet companion of Lent. Even today, the echo of this tradition lingers on regional tables. In hidden inns or small village restaurants, when they exist, fried carp is served, crisp and golden, almost ritual. |

|

|

|

|

| Long is the road that then stretches out, unhurried, along forest and meadows. It seems to advance without precise purpose, indifferent to destination, happy simply to follow the edge, to brush the grass, to caress the earth. Meadows spread wide, vast sheets where a few scattered animals sometimes graze, unhurried. In places, a patch of cultivation still dares, timidly, to pierce the green weave. Here, everything breathes the calm of an old world. |

|

|

| Then comes the edge of the plateau. There, as if the land were catching its breath, the road begins its descent toward Courcelles. The landscape opens briefly, offering a broad view, a suspended balcony over the valley. It is a gentle invitation, almost a bow, before plunging toward the village nestled in the folds of the hills. |

|

|

| Further on, the slope grows steeper, more direct, almost impatient. The road lets itself be carried downward, racing the hillside in a more decisive movement. One feels the weight of the journey here, the return toward habitation, toward the familiar, like a promise that pulls at the legs and quickens the step. |

|

|

| Here again, the signs keep watch. The scallop shell of Saint James continues to mark the route faithfully, luminous against blue, almost reassuring. A green triangle accompanies it, enigmatic, for whom, for what? Perhaps another route, another quest. The road, for its part, enters the village, slips between orderly houses, and passes before the church, a peaceful guardian of stone, standing like a prow in a sea of roofs. |

|

|

| Leaving the village, a small paved road slips away in turn, discreet and understated. Before losing itself once more in the countryside, it crosses the Coeuvatte, or the Mill Canal, depending on the maps and the memories. The current is discreet, almost secret, as if even its name hesitated to impose itself. A modest bridge spans this thread of water that still whispers stories of old mills, forgotten millstones, and vanished flour. |

|

|

| The road, now narrow and almost intimate, moves between fields and hedges, without jolt or effort. It runs straight toward the forest, like an arrow slowed down. The ploughed fields greet it with a shiver; the distant trees await it like a threshold. Silence here begins once more to take over, stretching alongside the road, ready to thicken again as soon as the woods are entered. |

|

|

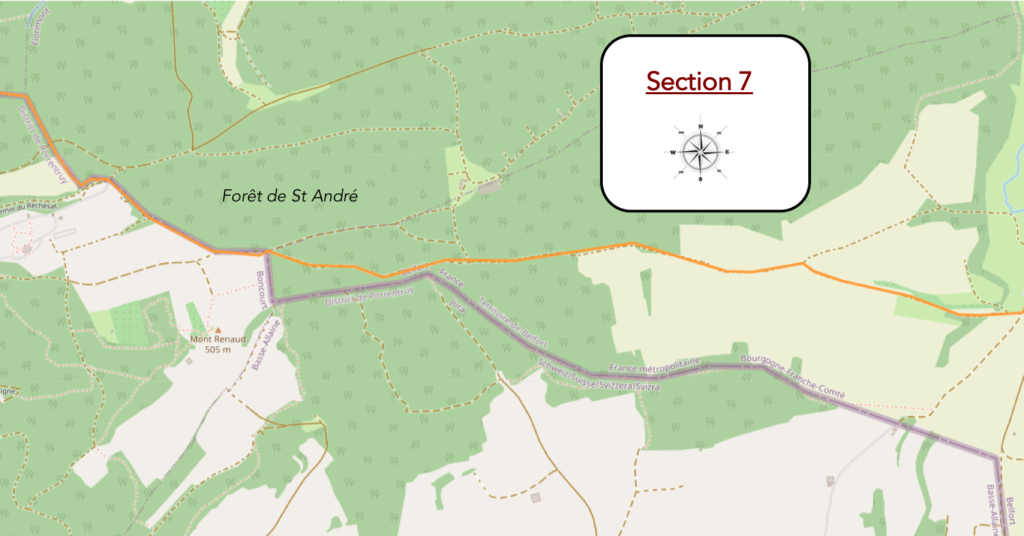

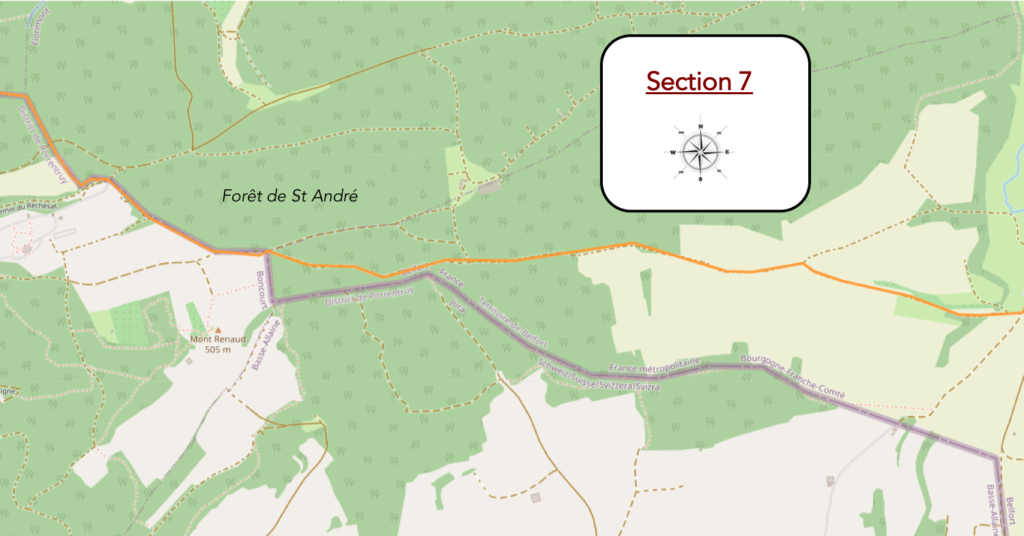

Section 7: Through the countryside, before the return of the woods

Overview of the route’s challenges: continuous gradients, with occasional sustained slopes.

| Quite early on, the asphalt fades away without a sound, giving way to a wide road of pale earth, smoothed by tractors and by the passing of seasons. It is a change of texture more than of direction, a discreet transformation in the body of the route. The step softens, soles find a new rhythm, gentler and more organic. This is no longer a road to be followed, but a vein of earth, warm and pulsing, inviting a slower pace. |

|

|

And suddenly, like a mischievous wink from fate, a golden scallop shell of Compostela reappears. It shines at last, clearly visible on wood or stone, proud to exist where so many others were missing. This time, the little fan it forms, that stylised sun, points in the right direction, like a star that has finally found north.

| The dirt road then slopes up gently. Little by little, you sense the approach of the forest edge. |

|

|

| The path narrows, becoming more intimate, as if hesitating between continuing forward or dissolving into the landscape. It follows the woodland edge for a few dozen metres, a discreet companion to the undergrowth murmuring nearby. . |

|

|

| Then it plunges, now stony, into the depths of the St André forest. There, beneath a vault of broadleaved trees and conifers, it winds for a long time. Spruces stand beside birches and beeches, lower, younger, less solemn. Hazel trees lift their supple arms in the half light. Yet it is the beech that retains its sovereignty, noble silhouettes, sometimes leaning, often impassive, watching over the forest like silent ancestors. |

|

|

| Here, the Camino de Santiago is marked with exemplary clarity, reassuring and guiding. But the reason is simple, the way is unique. No junctions, no traps. It is an obvious furrow, almost dictated by the landscape itself. |

|

|

| The undergrowth grows lighter, the tall trees retreat. Ancient beeches give way to a crowd of young shoots, dense regrowth with slender, almost feverish trunks. They form a silent army, eager to grow, to take their place. The path runs toward the light, slowly approaching the forest exit. |

|

|

| At last, after this long woodland crossing, the forest opens abruptly onto a vast clearing, sown with maize whose leaves rise like blades. And there, set down like stones of legend, the boundary markers reappear. Before you, two places emerge between sky and land, Delle and Boncourt, peaceful silhouettes on the horizon. |

|

|

| The path then begins a gentle descent, skirting imposing black railings that enclose a large private estate on the Swiss side. The bars, regular and cold, reveal well-tended trees and a domesticated landscape behind the fences. The path itself remains free, brushing this boundary of a closed world. |

|

|

| Further on, the path bends, grazing the meadows at the forest edge. It is a modest guiding thread, marked both by green rectangles and by scallop shells of Compostela. A double language, a double promise. But who are these rectangles for? They seem like forgotten signs, floating remnants, perhaps traces of an old route or of a marking that never found its audience. |

|

|

| A little further, the path crosses a small road, then immediately dives back into the forest. There, the first signs of the Swiss customs service reappear, small discreet plaques, mute signs of administration amid foliage. The path oscillates, uncertain, between two countries, a wooded corridor between jurisdictions. |

|

|

| Not far away, a small pond shimmers peacefully. If one continues straight ahead, following the forest instead of turning right, the route naturally leads to Boncourt, in Switzerland. A discreet alternative, offered without explanation, like a secret invitation to the curious. |

|

|

Not far away, a small pond shimmers peacefully. If one continues straight ahead, following the forest instead of turning right, the route naturally leads to Boncourt, in Switzerland. A discreet alternative, offered without explanation, like a secret invitation to the curious.

| But if you remain faithful to the route toward Delle, the path narrows again, becoming shaded, almost secret. It descends through the wood, brushing young beeches that line the slope. Each step here is a step of farewell. |

|

|

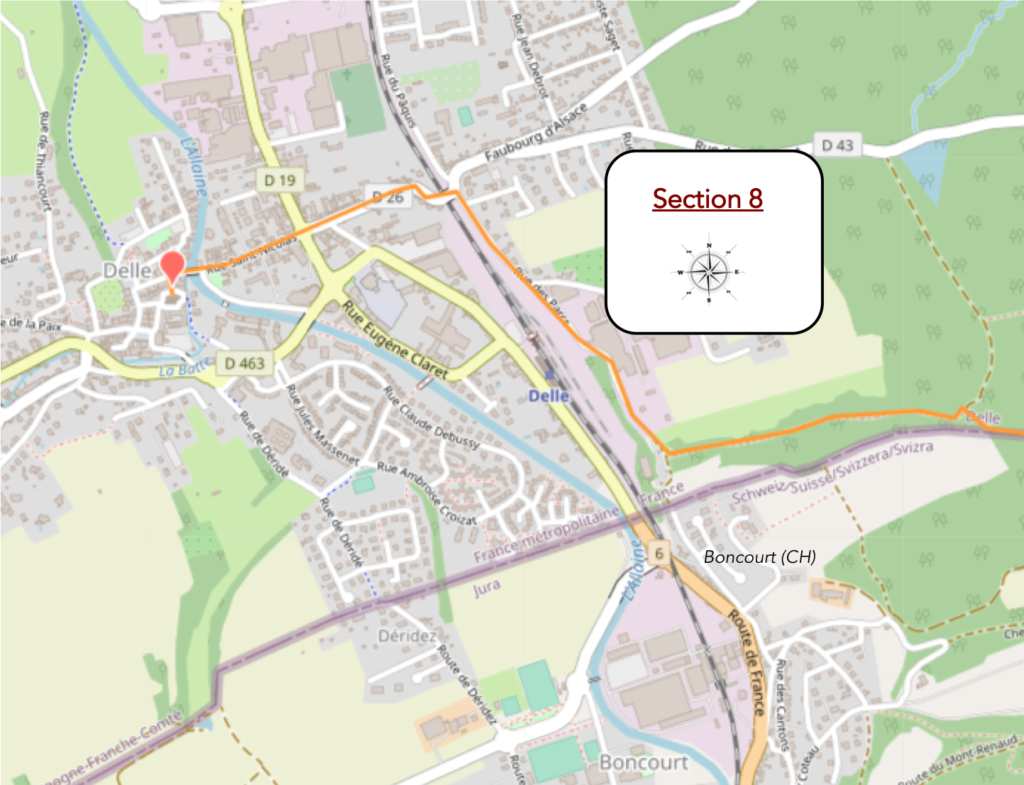

Section 8: Along the border

AOverview of the route’s challenges: a gentle descent.

| A narrow trail, almost shy, then slips into the undergrowth. It winds softly between young trunks, avoiding roots, brushing ferns. It feels like a trail made for those who wish to pass without disturbing the silence. Barely marked, almost secret, it seems to thread its way like a thought between two reveries, in the green shade of a closed world. |

|

|

| Then suddenly, the undergrowth opens, almost dissolves. The trail passes through a final curtain of brambles and bushes, then emerges into a broader, less vegetal space. There, set at the edge of this blurred territory, a Roma camp appears. It is an invisible border between two worlds, that of travel and that of settled ground. |

|

|

| A small road then takes over, running calmly alongside the railway line. To the left, the rails draw their steel line, stubborn and straight as a scar. To the right, the road, more modest, follows along obediently. Past and present stand side by side here, without looking at one another. |

|

|

Beyond the fences, Delle railway station emerges like a concrete ghost. It is still standing, but emptied of its breath. In 1992, the SNCF abruptly pulled the brake on the Belfort Delle line, then on the line that, on the Swiss side, continued to Boncourt. Three years later, the station itself was decommissioned, left abandoned like so many other places sacrificed in the name of profitability. Yet in 2006, a glimmer returned. A short section, barely 1,600 metres, was put back into service between Delle and Boncourt, thanks to Swiss funding, quicker to believe in the usefulness of a link than France, which still drags out its works between Delle and Belfort. On our last visit, Swiss trains were still shunning this station, like a spurned lover. And we, pedestrians, spectators of a slow and uncertain project, could only sigh, poor France !

| The small road, unperturbed, continues to follow the railway line, here called Rue des Parcs. The place has little sparkle, utilitarian, almost anonymous. Yet it fulfils its role as a zone of transition, between the territory of rails and the first houses of Delle. |

|

|

| At the end of Rue des Parcs, the route shifts. It crosses the tracks by a small bridge or discreet crossing and descends toward the heart of the town. The slope steepens slightly, as if to mark entry into the urban, the built, the inhabited. Walking becomes less solitary, the landscape denser. |

|

|

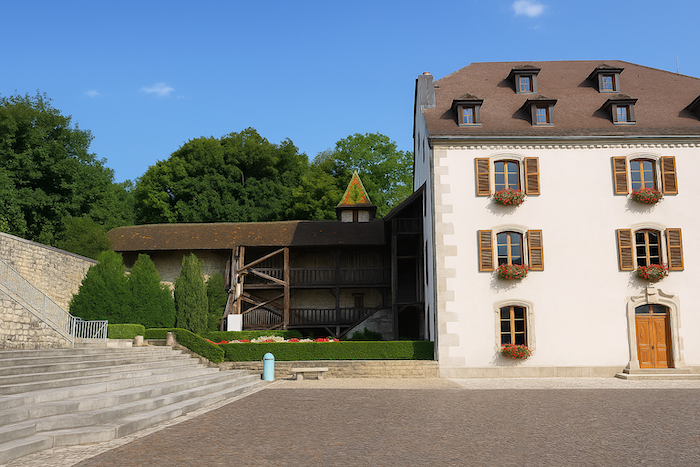

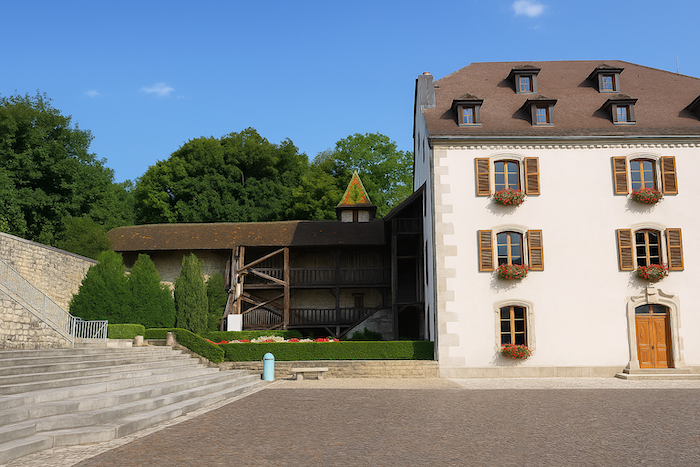

| At the level of the town centre, the Allaine flows, calm and almost indifferent to human bustle. It crosses the town like a slow breath, bordered by discreet walls and damp foliage. Delle, with its roughly 5,600 inhabitants, is the second town of the Territoire de Belfort, after its eponymous capital. A modest but fragmented town, composed of peripheral neighbourhoods with the feel of housing estates, surrounding an older centre, somewhat compact yet not without charm. One discovers a few remnants there, an old hospital, forgotten stretches of ramparts, houses crowned with turrets, memories of another time, another order. The church of St Léger embodies this turbulent history. Rebuilt at the beginning of the twentieth century, it carries in its stone the tribulations of past centuries, wars, reconstructions, neglect, rebirths. Today it raises its pale silhouette as a reminder at the centre of a town that is both simple and layered. On the other side of the town lies Boncourt, in Switzerland. |

|

|

|

|

Official accommodations in Burgundy/Franche-Comté

- Au Soleil, 17 Rue du Général Giraud, Liebsdorf; 03 89 40 80 24; Hotel

- Les petites chambres en couleurs, 22 Faubourg d’Alsace, Delle; 06 21 95 51 57; Guestroom

- Claudie Bérard, 30bis Avenue Général de Gaulle, Delle; 06 20 11 61 97; Guestroom

- Hôtel du Nord, 4 Faubourg de Belfort, Delle; 06 07 71 75 41; Hotel

- B&B Vinita, Route de Déridez 24, Ancienne douane, Boncourt (CH); 079 574 20 80; Guestroom

Jacquaire accommodations (see introduction)

Airbnb

- Pfetterhouse (2)

- Delle (6)

Each year, the route changes. Some accommodations disappear; others appear. It is therefore impossible to create a definitive list. This list includes only lodgings located on the route itself or within one kilometer of it. For more detailed information, the guide Chemins de Compostelle en Rhône-Alpes, published by the Association of the Friends of Compostela, remains the reference. It also contains useful addresses for bars, restaurants, and bakeries along the way. On this stage, there should not be major difficulties finding a place to stay. It must be said: the region is not touristy. It offers other kinds of richness, but not abundant infrastructure. Today, Airbnb has become a new tourism reference that we cannot ignore. It has become the most important source of accommodations in all regions, even in those with limited tourist infrastructure. As you know, the addresses are not directly available. It is always strongly recommended to book in advance. Finding a bed at the last minute is sometimes a stroke of luck; better not rely on that every day. When making reservations, ask about available meals or breakfast options..

Feel free to leave comments. That is often how one climbs the Google rankings, and how more pilgrims will gain access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 3: From Delle to Hericourt |

|

|

Back to menu |