A story of squares, rectangles, dots, and diamonds, in every colour

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

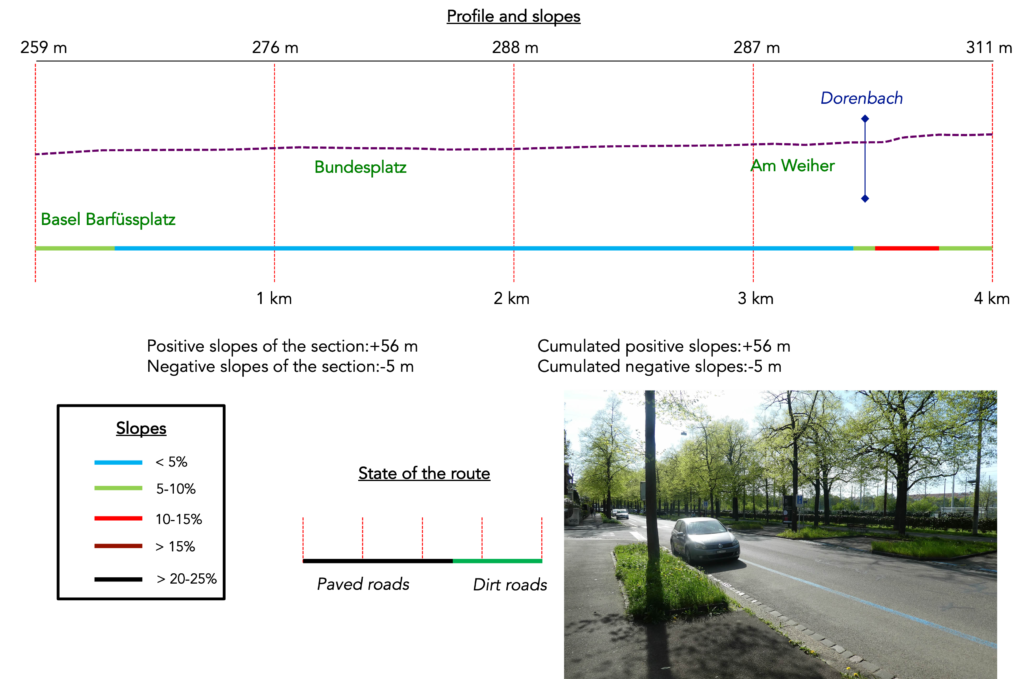

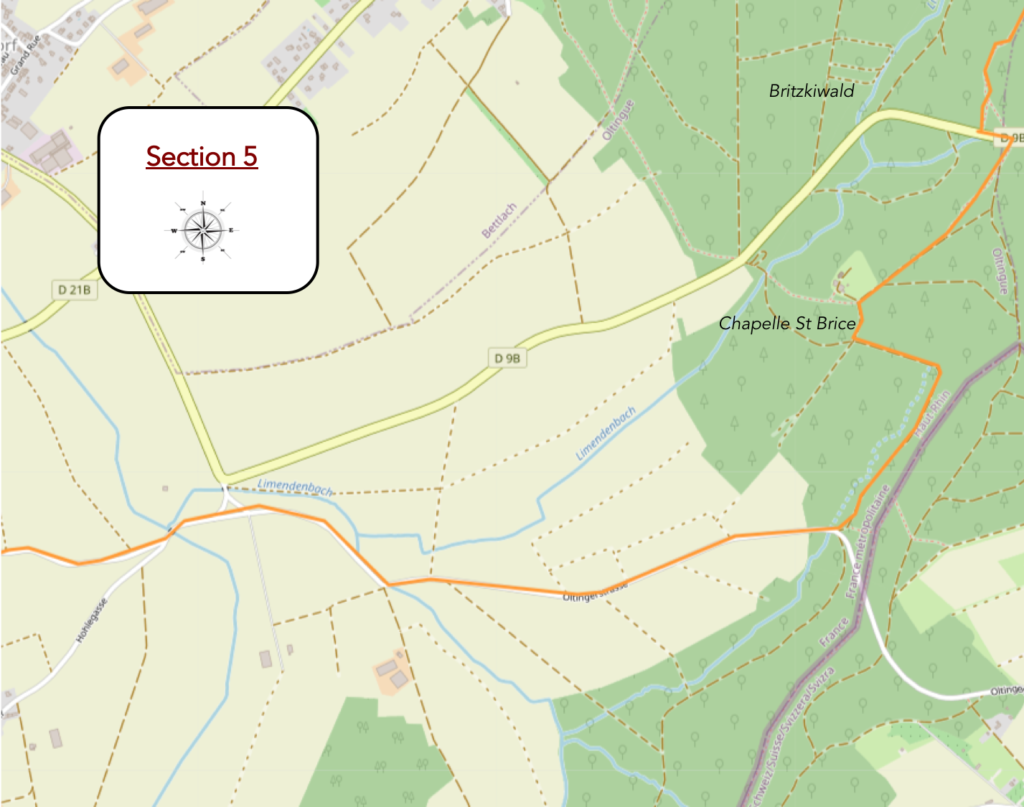

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-b-a-ferrette-par-le-chemin-de-compostelle-81881428

| This is obviously not the case for all pilgrims, who may not feel comfortable reading GPS tracks and routes on a mobile phone, and there are still many places without an Internet connection. For this reason, you can find on Amazon a book that covers this route.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page. |

|

It was on a rocky spur, rising like a stone prow above the Alsatian forests, that Frederick I of Ferrette, from the powerful lineage of the Counts of Montbéliard, decided to raise his fortress in the twelfth century. From this eagle’s nest, the County of Ferrette gradually wove its web of influence over medieval Upper Alsace, until it became one of the most feared and respected lordships in the region. Calculated marriages, strategic conquests, vassal loyalties, the territory grew like a tree with deep roots and daring branches. Yet greatness always attracts envy. In the thirteenth century, the gaze of the powerful Bishop of Basel, an ambitious neighbour, settled insistently upon this rising power. Caught in the turbulence of feudal rivalries, the county even fell into the hands of the Basel authorities. In the centuries that followed, the county’s coat of arms changed hands in step with the alliances and ambitions of Europe’s great powers. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, it was first seized by the Habsburgs of Austria, before slipping under the turbulent authority of the Burgundians of Charles the Bold. These successive dominations left their mark on the castle, which was enlarged, fortified, and reshaped to embody the majesty of its new masters. Governor succeeded governor, each a local cog in a distant power, the custodian of an order imposed from elsewhere. The county now lived to the rhythm of chanceries and princely courts rather than that of its own lands.

But History, never sparing in fury, unleashed its storm upon these walls during the Thirty Years’ War. The seventeenth century rained blows of destruction upon the castle. Swedish armies rushed in, followed by the French, spreading pillage and ruin in their wake. When the Treaty of Westphalia finally put an end to the haemorrhage, Austria, bled dry, ceded vast portions of its empire. Upper Alsace, until then an imperial province, entered the orbit of the Kingdom of France. Louis XIV, in a gesture typical of his policy of territorial integration, granted the region to his loyal Cardinal Mazarin, including Ferrette, Belfort, Delle, Thann, an entire constellation of lordships gathered into his purse. Time moved on, erasing old conflicts beneath the crowns of princely marriages. The cardinal’s descendants inherited the estate, until in 1777 a marriage transferred it into the hands of the Monegasque dynasty. Even today, the princes of Monaco retain the largely symbolic title of Counts of Ferrette. From time to time, they even come to greet the local population, welcomed with joyful and curious enthusiasm. Yet despite this princely breath, the castle itself has not risen from its ashes. Abandoned to the centuries, given over to stone and silence, it was dismantled by peasants during the French Revolution, who saw in its walls a more useful quarry than a relic. From fortress it became stone pit. Listed as a historic monument in 1930, it is now little more than a skeleton watched over by the wind, a ghost of history patiently maintained.

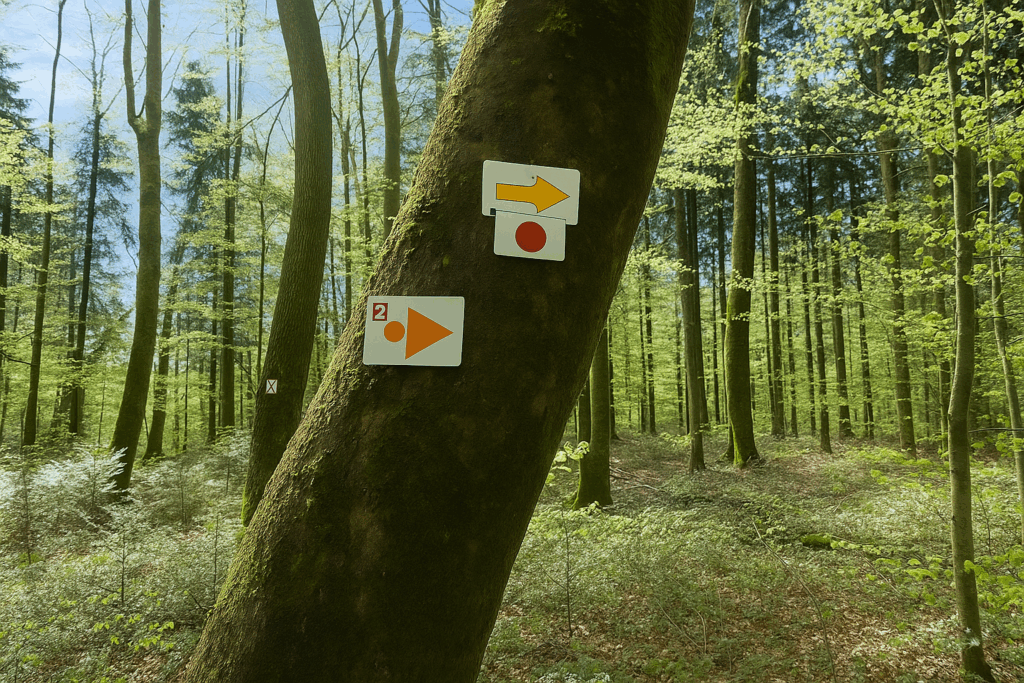

And yet, it is not this fallen grandeur that makes this stage difficult. It is neither the harshness of the terrain nor the fatigue of the journey. No, the challenge of the day lies elsewhere, in orientation. Here, the walker is confronted with a tangle of paths, like threads knotted into a tapestry of confusion. Squares, rectangles, diamonds, dots, an entire coloured geometry scatters across the landscape, sometimes guiding, often misleading. An excess of markings undermines clarity, and the pilgrim to Santiago, almost an intruder in these lands, must show sustained attention in order not to be swallowed by the labyrinth. Courage. With the map in one hand and patience in the other, you will eventually rediscover the thread of the route. And who knows? Perhaps at a bend along one of these capricious paths, the soul of the old county will still whisper a few forgotten secrets to you.

How do pilgrims plan their route. Some imagine that it is enough to follow the signposting. But you will discover, to your cost, that the signposting is often inadequate. Others use guides available on the Internet, which are also often too basic. Others prefer GPS, provided they have imported the maps of the region onto their phones. Using this method, if you are an expert in GPS use, you will not get lost, even if the route proposed is sometimes not exactly the same as the one indicated by the shells. You will nevertheless arrive safely at the end of the stage. In this context, the site considered official is the European Route of the Ways of St. James of Compostela, https://camino-europe.eu/. For today’s stage, the map is accurate, but this is not always the case. With a GPS, it is even safer to use the Wikilocs maps that we make available, which describe the current marked route. However, not all pilgrims are experts in this type of walking, which to them distorts the spirit of the path. In that case, you can simply follow us and read along. Every difficult junction along the route has been indicated in order to prevent you from getting lost.

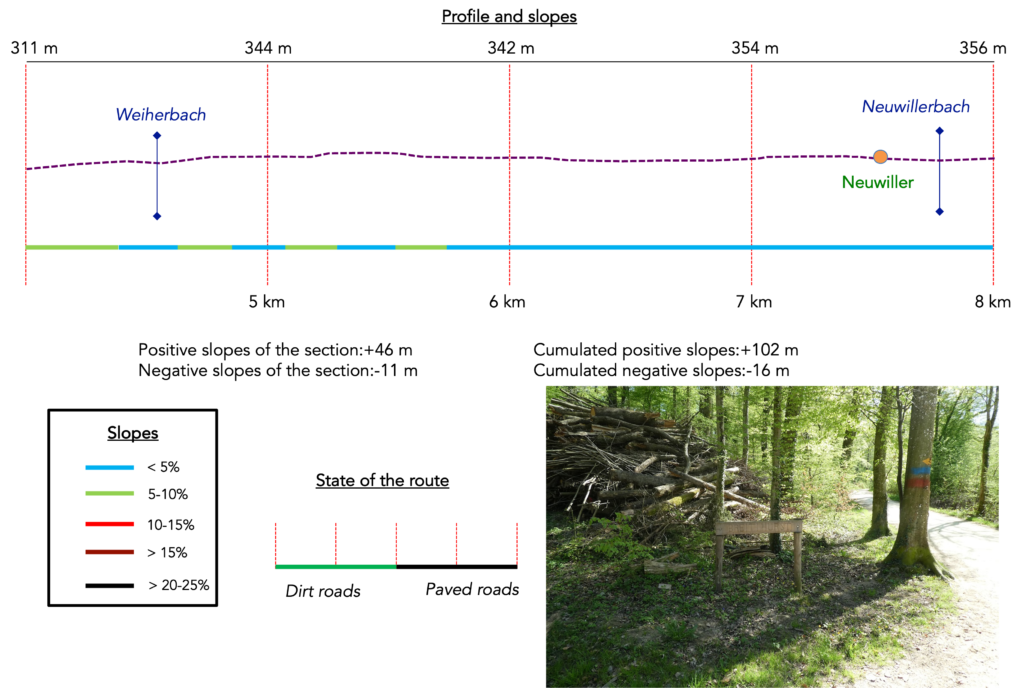

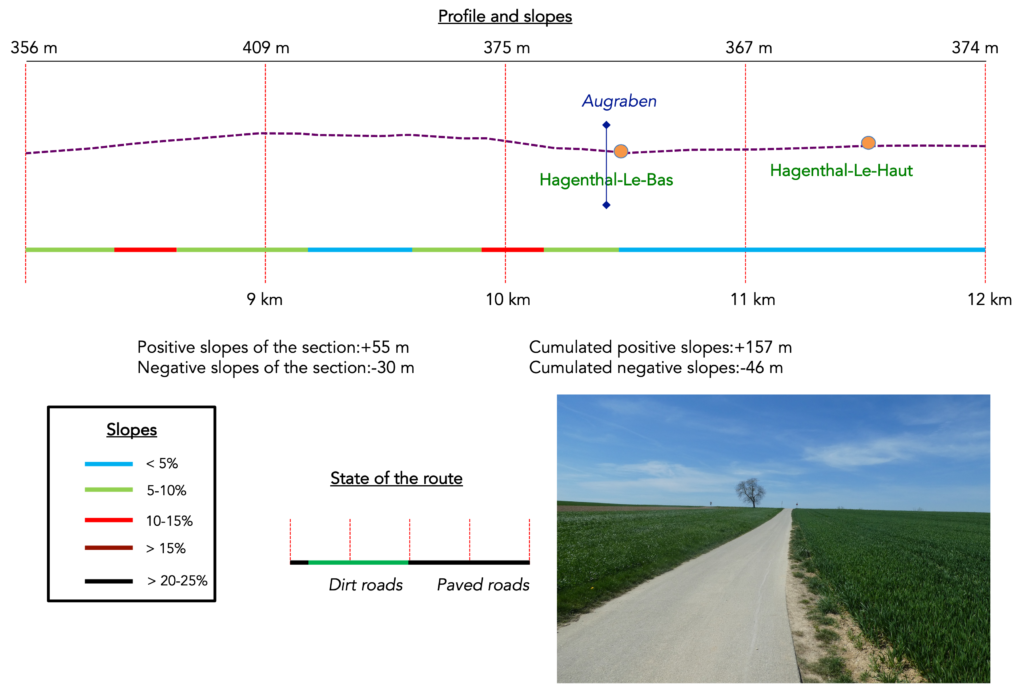

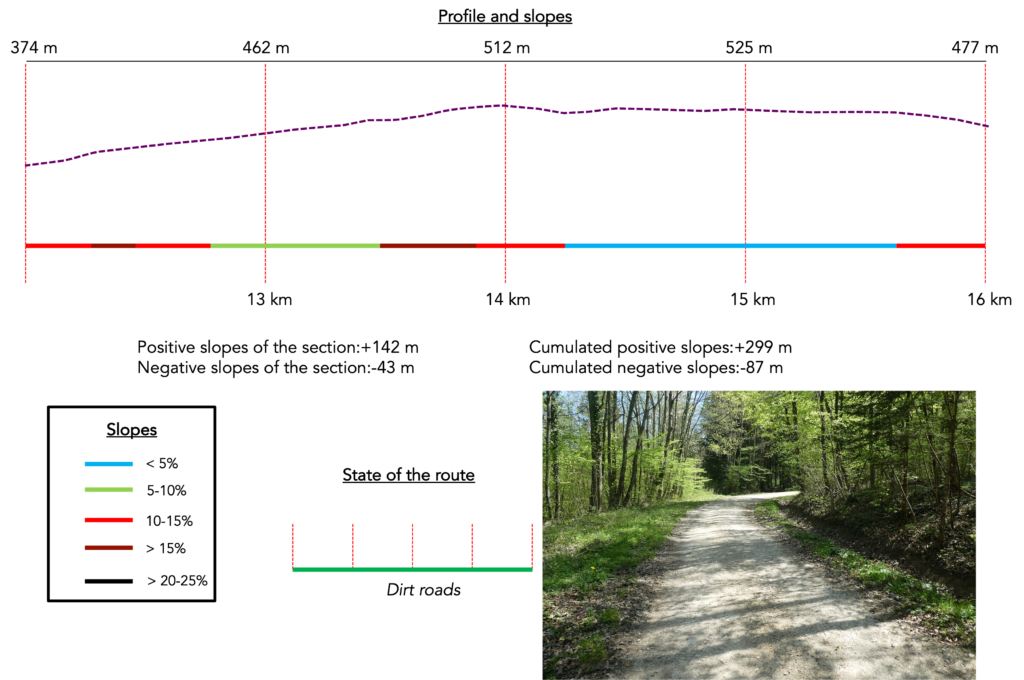

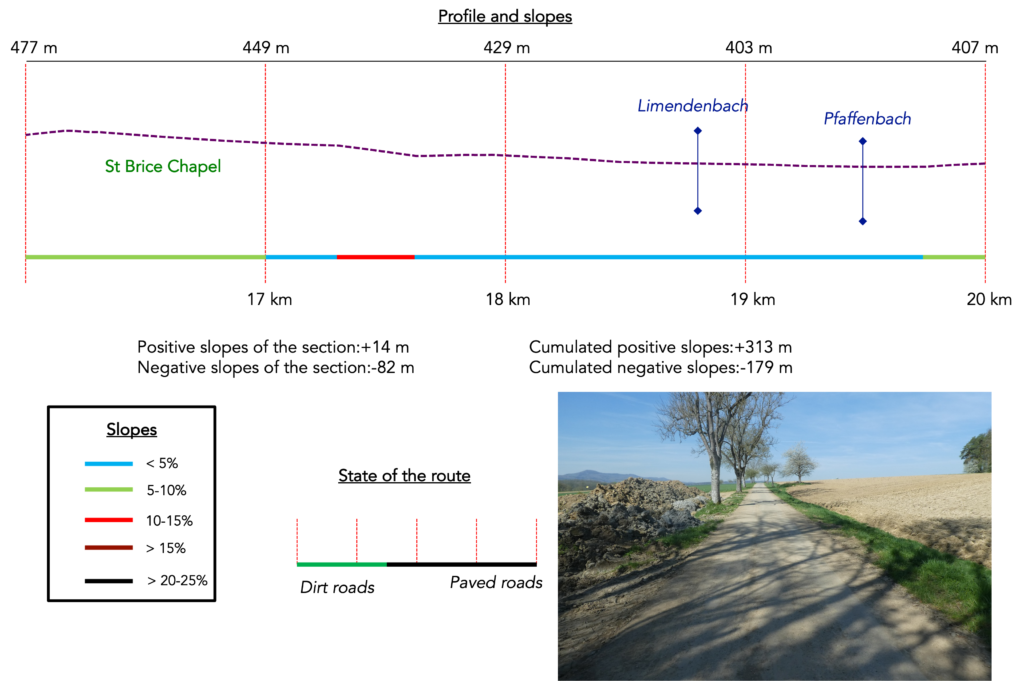

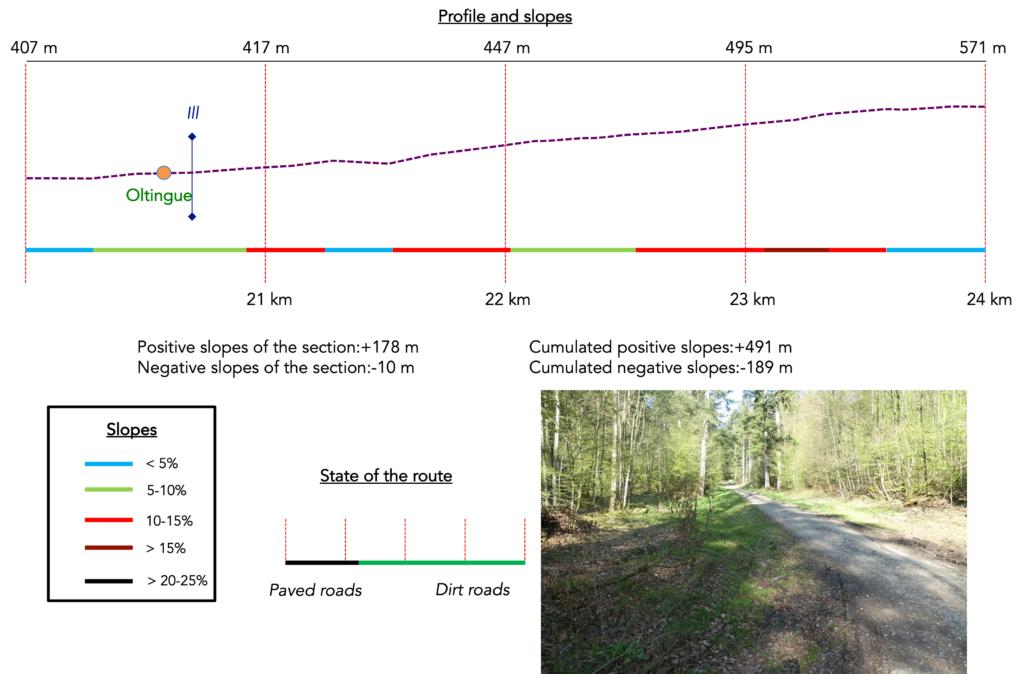

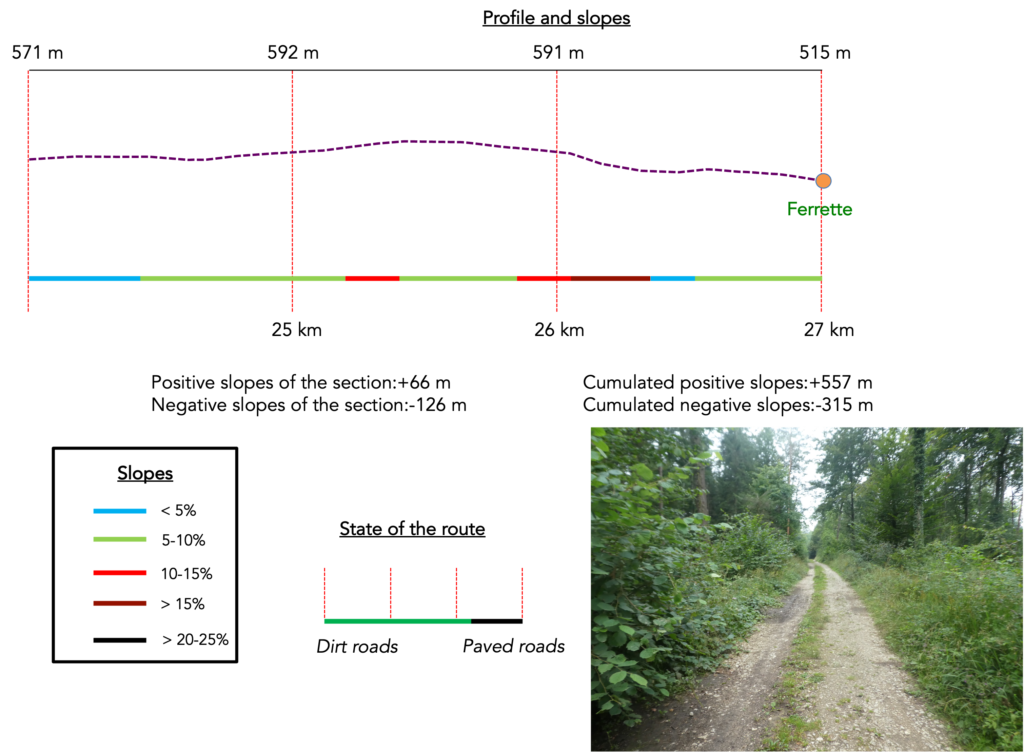

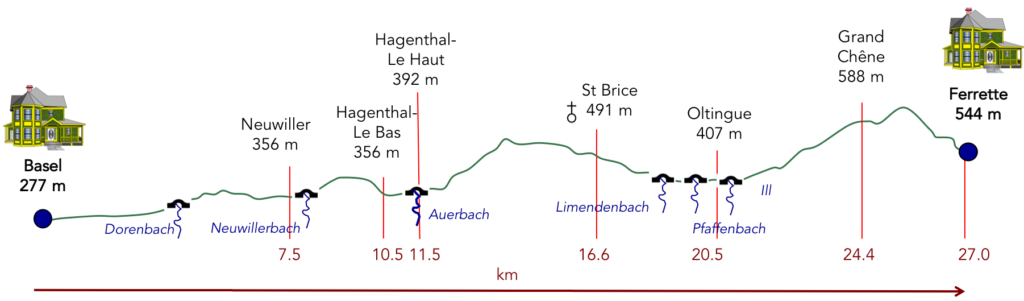

Difficulty level: The route is not without challenges, although the elevation gain and loss (+ 557 meters /- 315 meters), remain fairly reasonable for such a long stage. For many kilometres before entering France, the terrain consists of gentle undulations. Then the route follows two long climbs, the St. Brice climb and above all the climb before reaching Ferrette.

State of the route: Today, this is a stage that pilgrims appreciate. There is more dirt track than asphalt:

- Paved roads: 11.2 km

- Dirt roads: 15.8 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

A short walk through Old Basel before setting out on the route

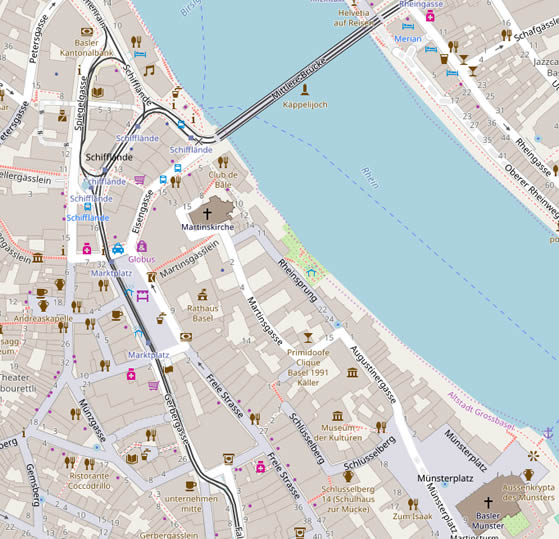

Whether one is Swiss and starting out here, or arriving from Germanic lands or from farther east, one must first, inevitably, come to terms with Basel. This is not merely a simple crossing of a city, but a true rite of passage. Basel, proud of its 180,000 inhabitants, stands as the third Swiss city, just after Zurich and Geneva. It spreads with both gravity and gentleness, divided into some twenty districts, yet it is in the heart of two of them that the urban soul truly beats, Gross Basel, Great Basel, firmly anchored on the left bank of the Rhine, and Klein Basel, Little Basel, facing it on the opposite side of the river. The city centre, surprisingly, breathes without cars. Broad avenues are animated by long tramways that glide silently until nightfall. Here, pedestrian crossings are barely suggested, lightly traced, as pedestrians weave naturally between stopped buses or slowly decelerating trams. This is a city that listens to itself and invites passage more than it imposes itself. Let us begin our stroll in GrossBasel, in the vibrant hollow of Marktplatz, the Market Square.

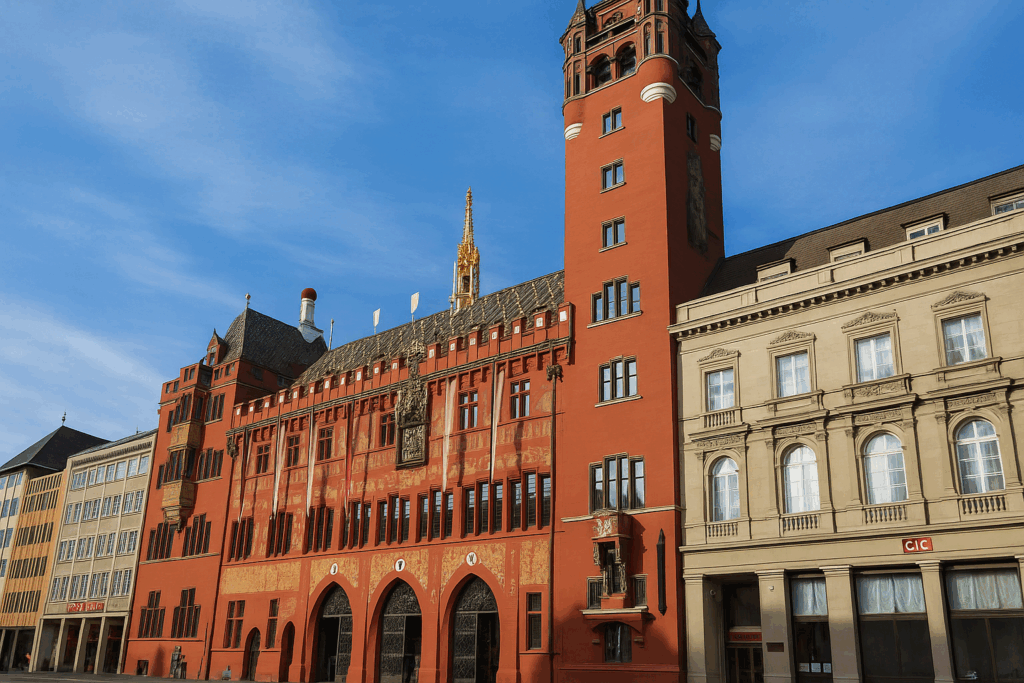

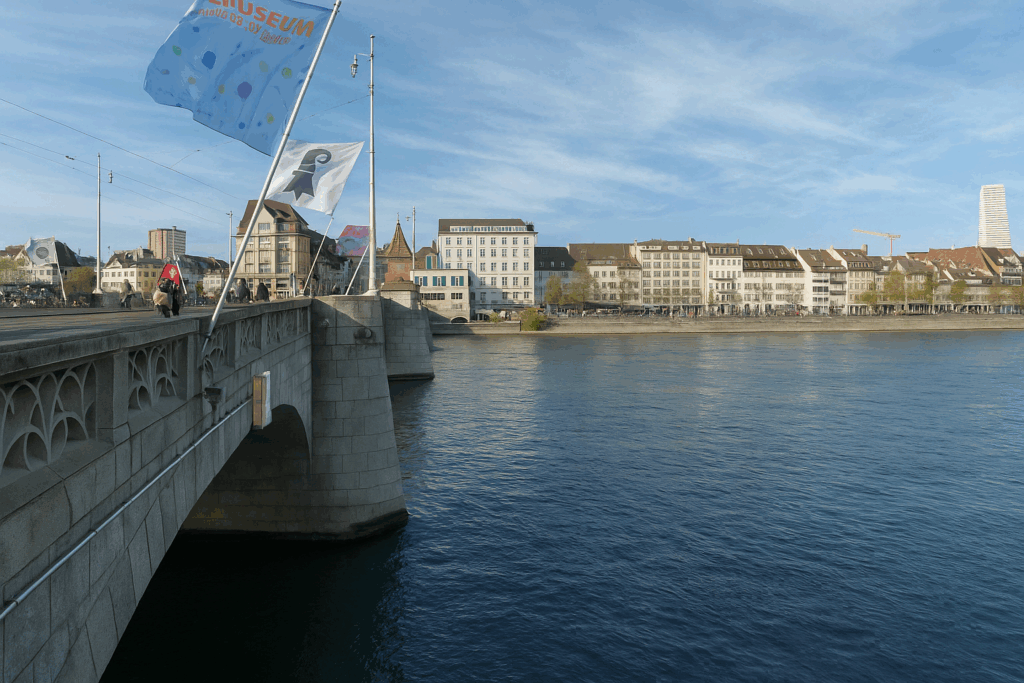

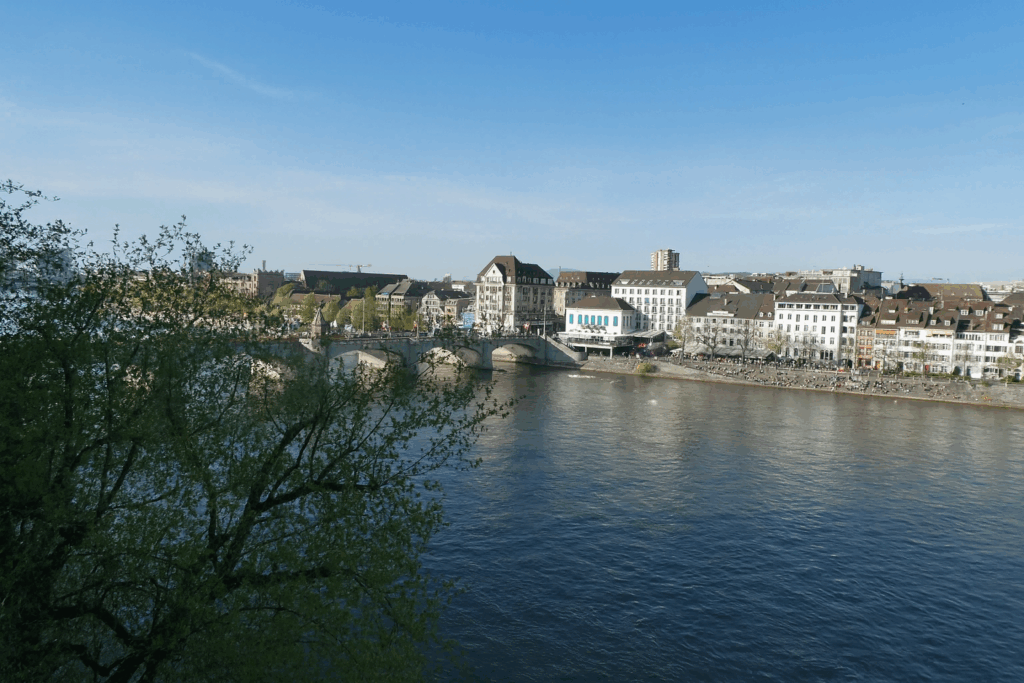

| Brilliantly dominated by the town hall, a vast carmine red building adorned with frescoes and turrets, the square serves as the daily stage of Basel life. This building, seat of the cantonal government, seems to watch over both crowd and market stalls. From Monday to Saturday, colours and scents compete for space. Here, days rise on fragrances. Now head up toward the Rhine. You emerge onto the Mittlere Brücke, the Middle Bridge, one of the oldest and most emblematic in the city. | |

|

|

| This bridge is far more than a simple link between two banks. It is the historic bond between the Basel of yesterday and that of today. On sunny days, the surrounding riverbanks turn into vast natural benches, where residents come to lie down, read, chat, or simply soak in the light. Beyond the bridge stretches Kleinbasel, long perceived as a second-tier Basel. Less monumental, certainly, but today enjoying growing popularity. Lined with bars, lively squares, and riverside terraces where glasses are raised beside the water, it has become a vibrant and festive district. But this morning, this is not where you are headed. | |

|

|

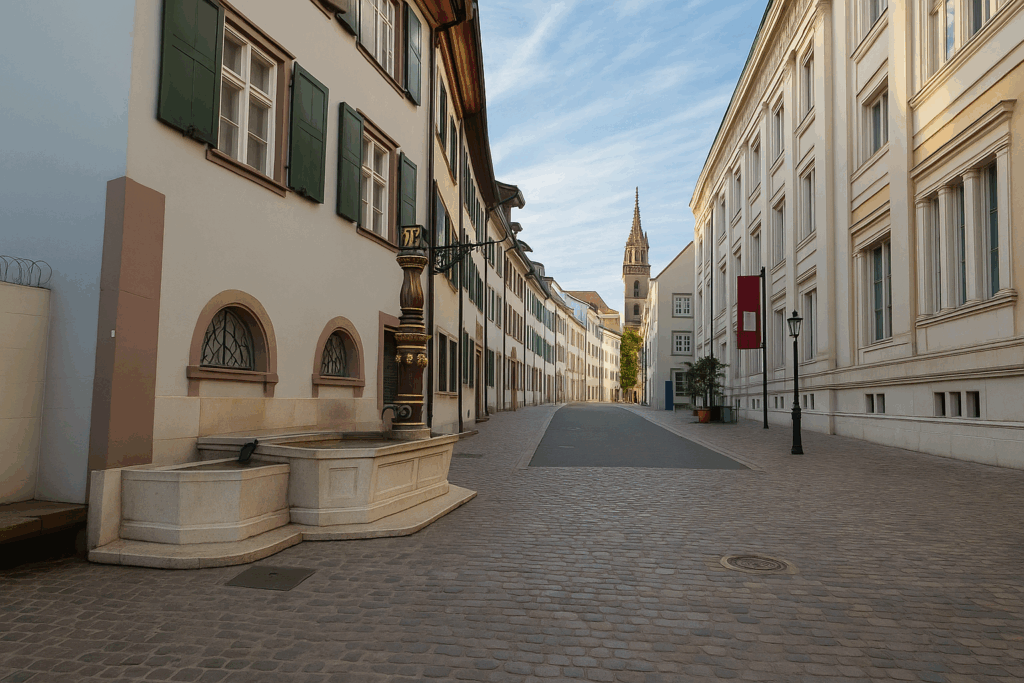

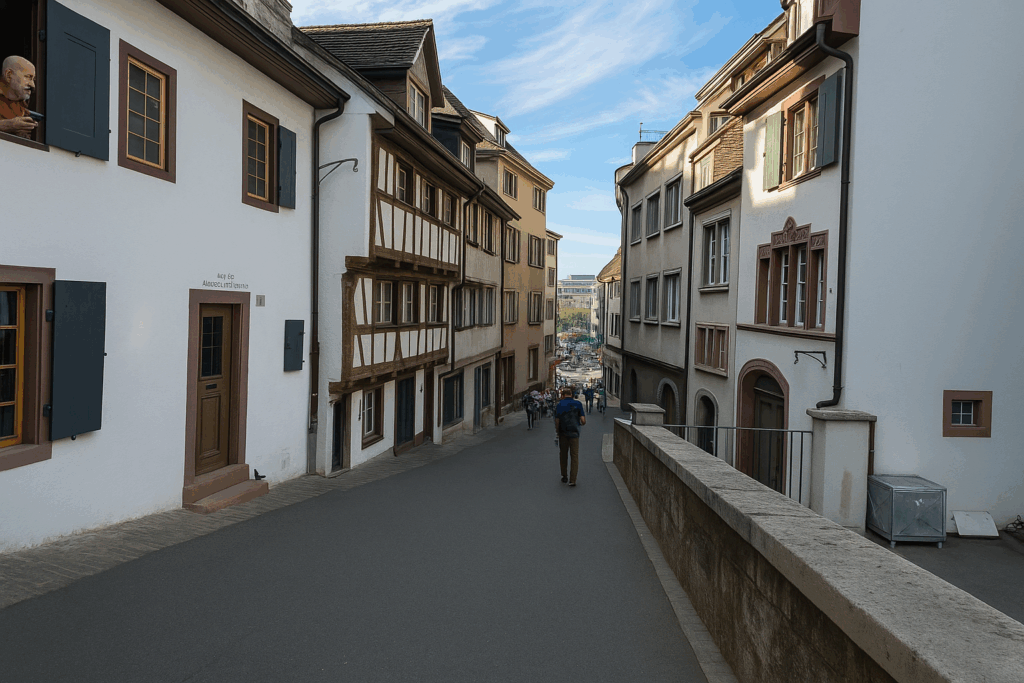

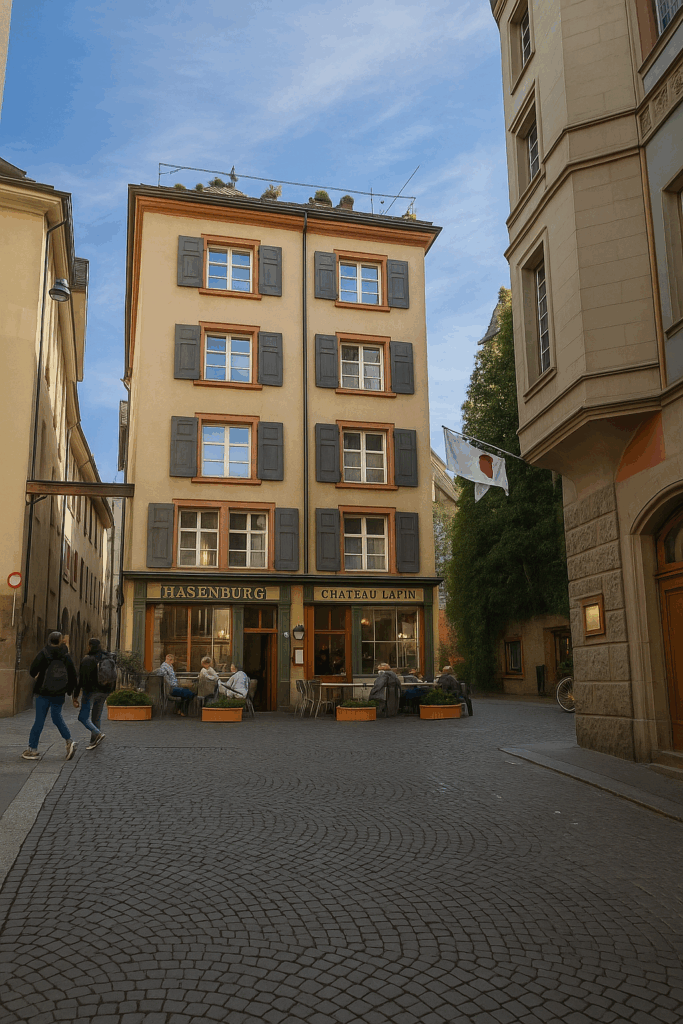

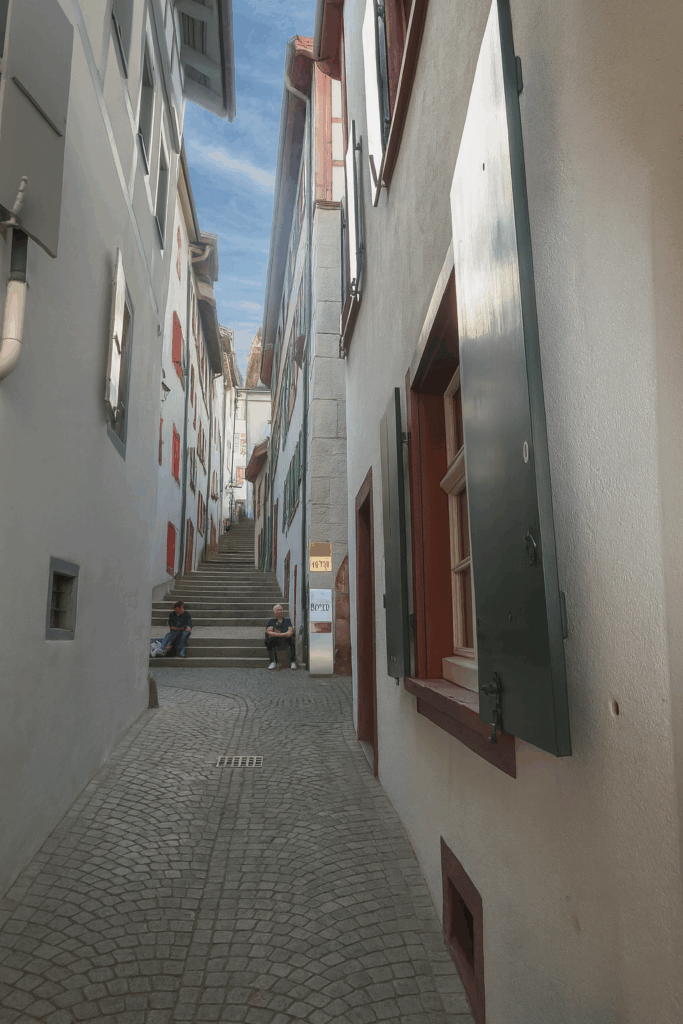

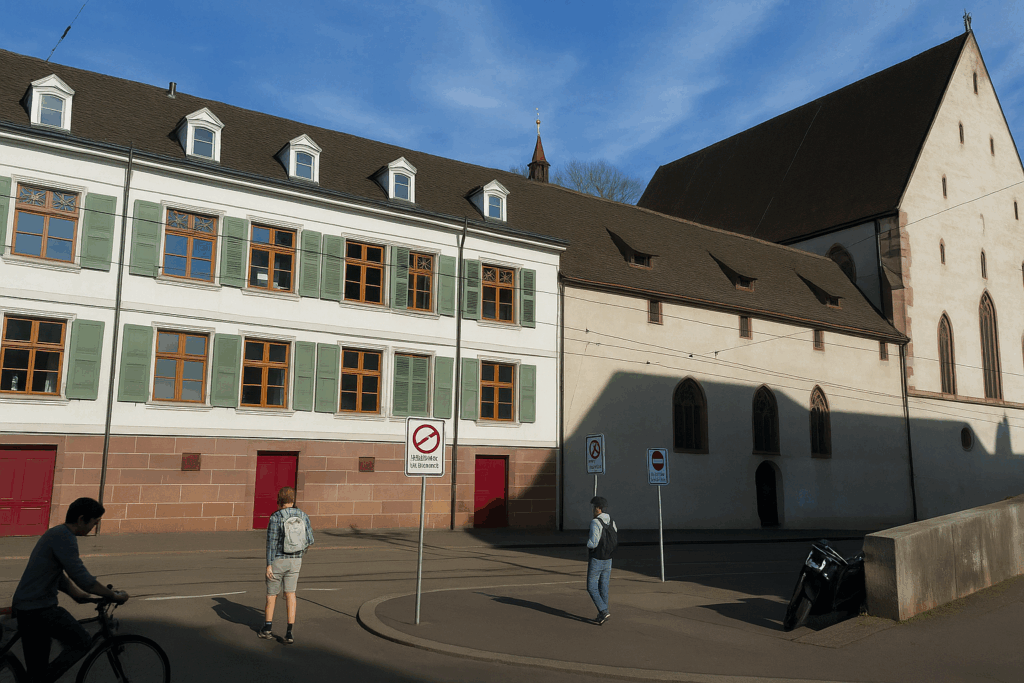

| If you choose, on the left side of the bridge, to orient yourself toward the cloister, you will need to climb, gently but steadily, through narrow cobbled streets, as there is no direct passage along the river at this point. The alleys, narrow and steep, wind between old facades. At every step, they seem to recount centuries of quiet life, of slow walks and confidences whispered to stone. The ascent leads you into one of the most charming streets in the district, Augustinergasse, paved with worn stones and graceful curves. | |

|

|

|

|

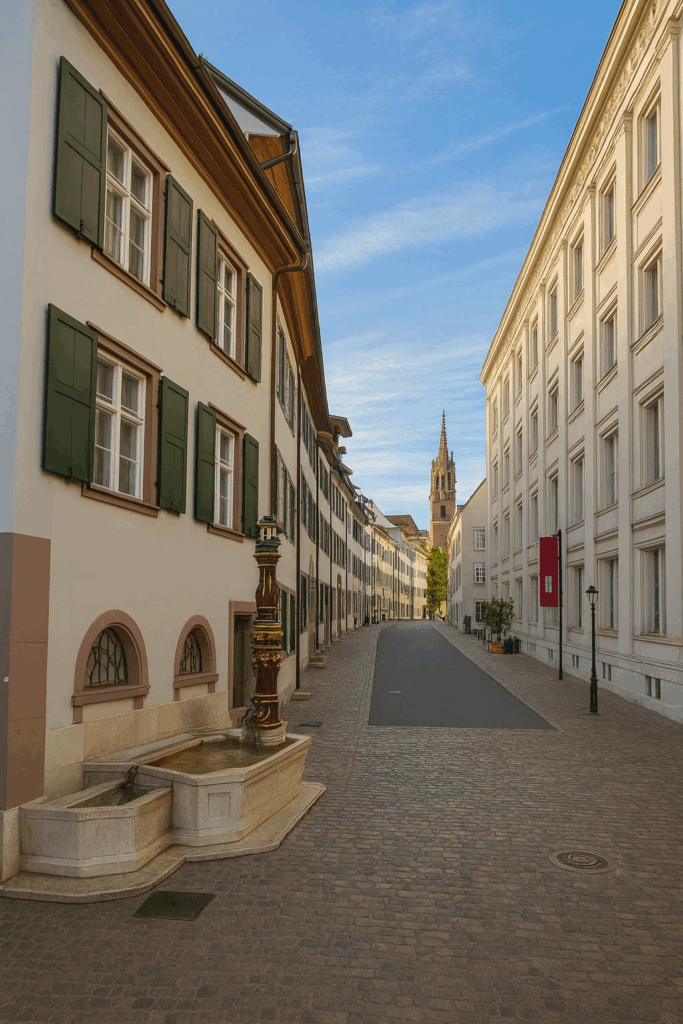

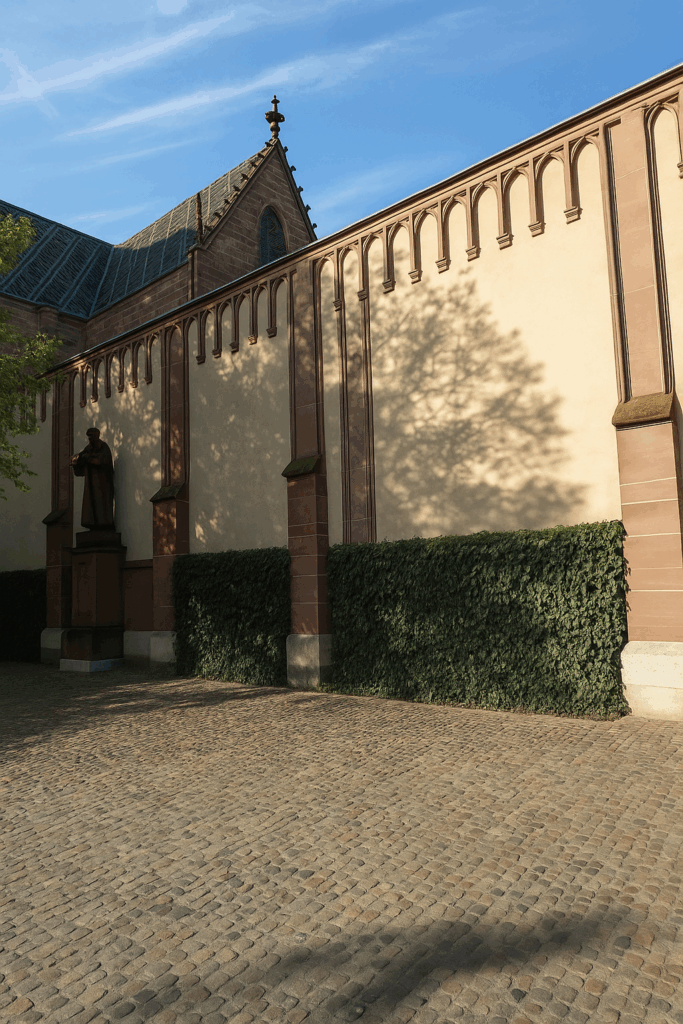

It appears suspended in time, removed from commercial bustle. Here, there are no flashy shop windows or loud signs. It is an approach route toward the cathedral, almost an inward walk. Finally, at the top of this peaceful climb, you reach an area where silence becomes an ally. In this quiet recess of the city, shops fade away, giving way to a kind of architectural breathing space. The walls seem to welcome you silently, as in a roofless cloister. You enter a different temporality, that of contemplation, where every detail matters and every stone seems laden with memory.

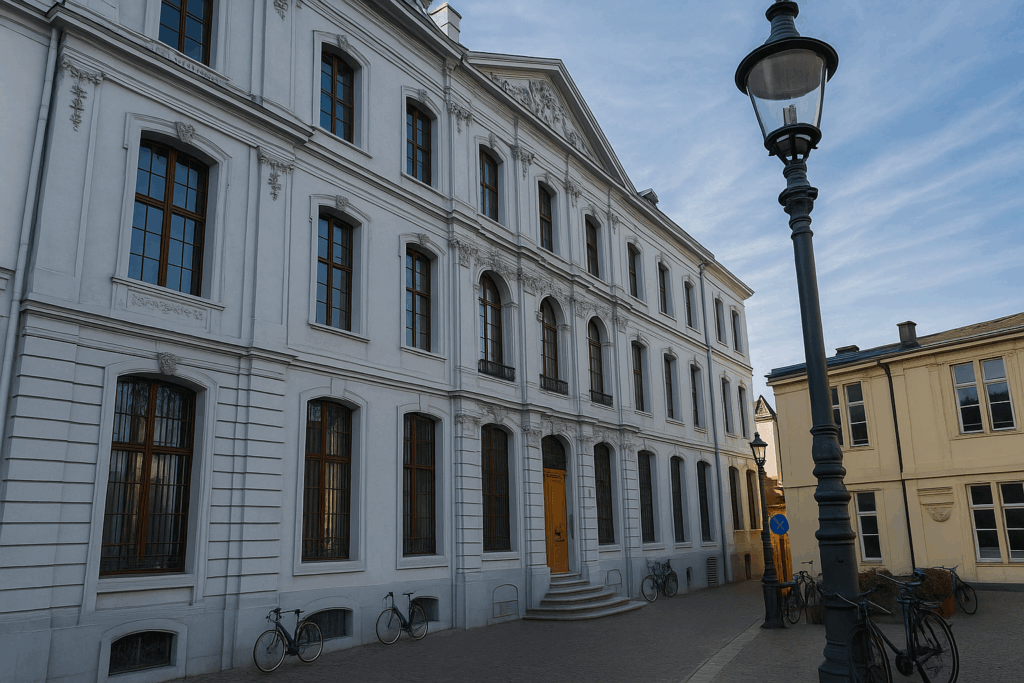

| In the patrician part of the city, a discreet yet profound charm asserts itself. Here, the houses appear to whisper their own history to those who know how to read the walls. They display a remarkable feature, a plaque, engraved or painted, bearing a name and a date, not that of a recent restoration, but the very year of their birth. According to these inscriptions, some of these buildings would date back to the fourteenth century. | |

|

|

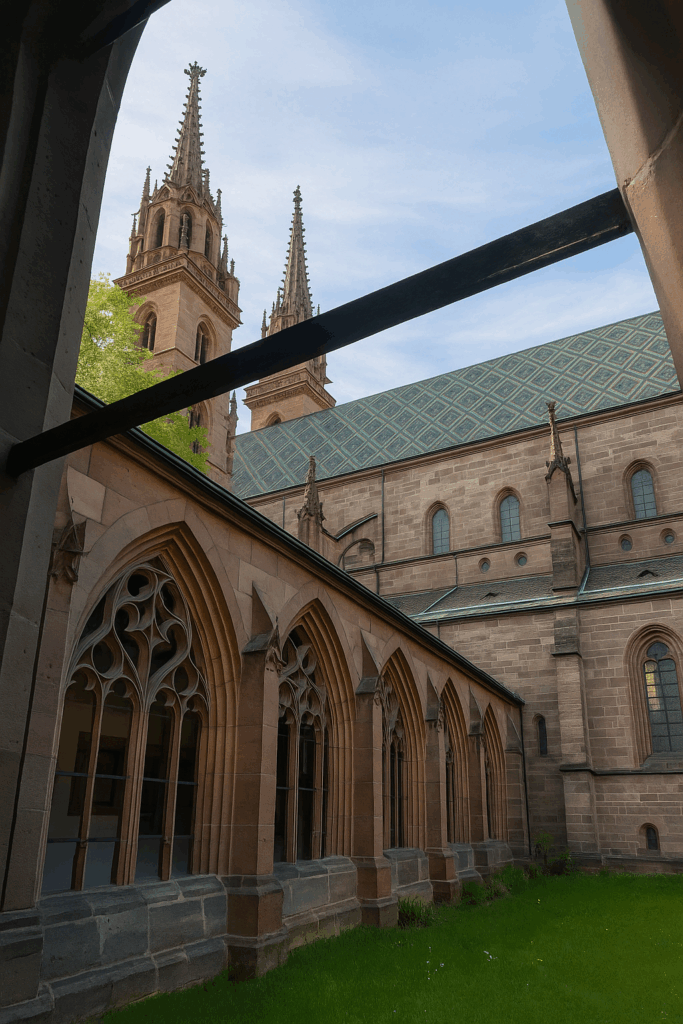

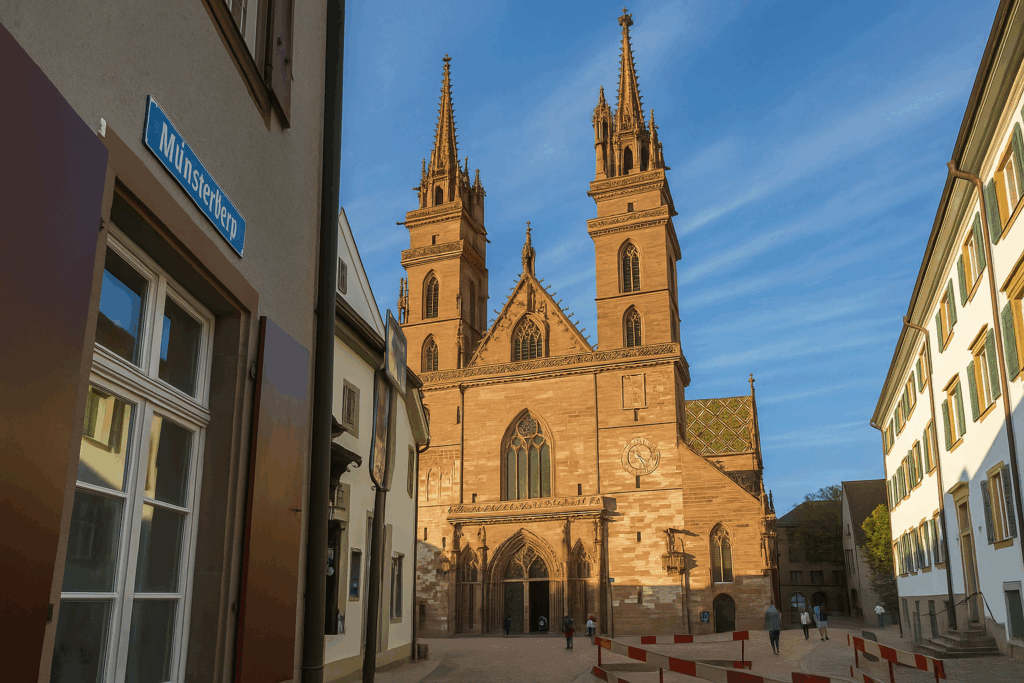

At the end of Augustinergasse, the alleyway opens onto a broad square steeped in history, Münsterplatz, dominated by the majestic silhouette of the cathedral. The Basler Münster, or Cathedral of Our Lady of Basel, imposes its presence in a glow of pink sandstone, a soft and warm colour that seems to capture both light and memory. A first Romanesque church was built here in the twelfth century. From that period remain a few vestiges, including the nave, austere and deeply moving. Gothic additions followed, subtle at first, then more pronounced. In 1356, an earthquake destroyed a large part of the building. Reconstruction then began with fervour and ambition, resulting in a flamboyant Gothic church, as if answering catastrophe with an upward impulse toward the sky. The Reformation, in 1529, transformed the cathedral into a Protestant church. Since then, it has undergone little change. On that day, the doors were closed, as a classical music concert was taking place, preserving its mystery for another visit.

| In the adjoining cloister, long abandoned by monastic functions, there now reigns an atmosphere of surprising gentleness. The silence is dense without being oppressive, footsteps soften naturally, and the eye drifts beneath arches and shadows. Everything here invites slowness, contemplation, and a quiet dialogue with the past. | |

|

|

Leave behind this haven of peace to return to the vibrant heart of the city.

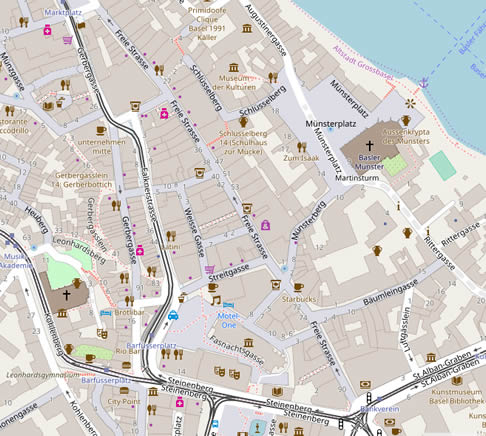

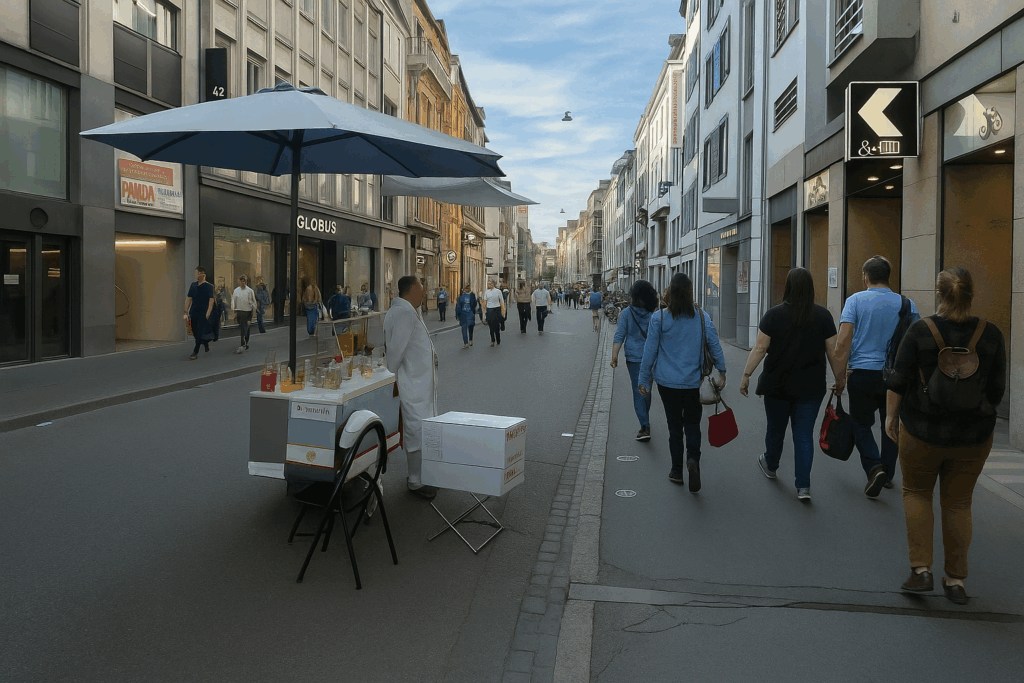

| To do so, the street descends from Münsterplatz via Münsterberg. This gently sloping street gradually brings you back to animation. It opens onto Freie Strasse, a wide commercial avenue where major contemporary brands integrate discreetly into an ancient urban fabric. | |

|

|

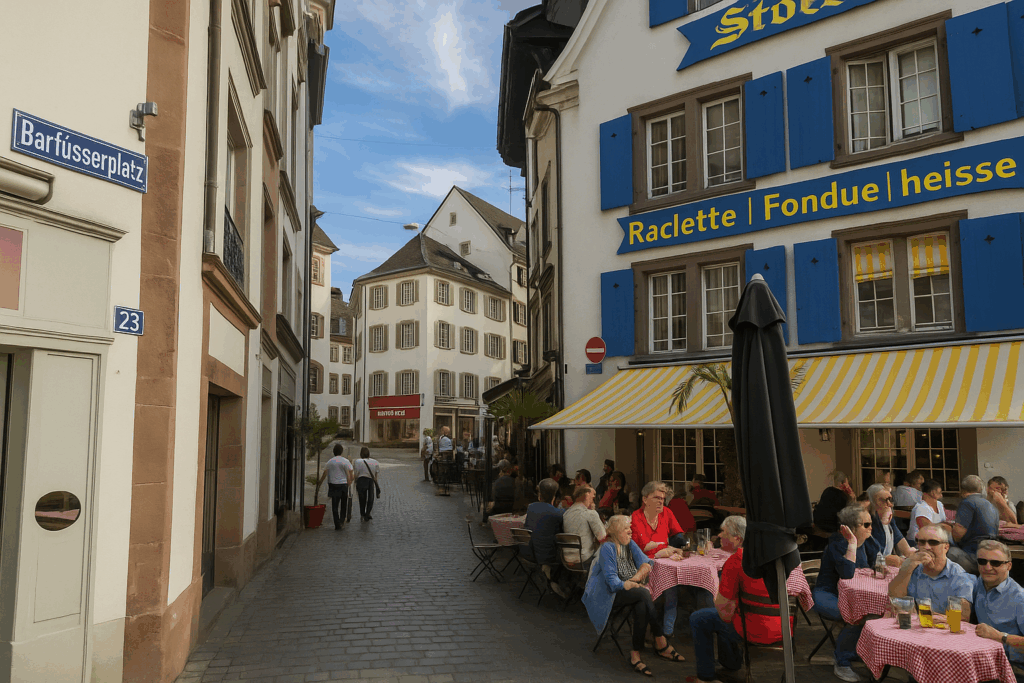

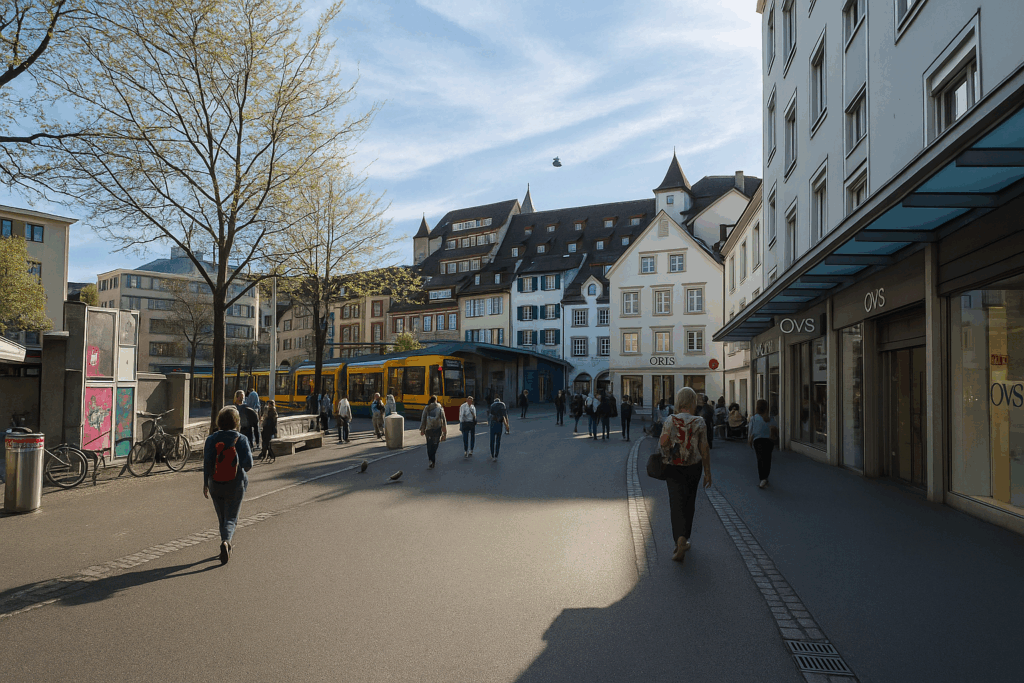

| By then taking Streitgasse, you reach Barfüsserplatz, the Barefoot Square, named in homage to the former Franciscans. Impossible to miss, it hums with life at all hours. This is likely where Basel pulses most strongly. Tramways follow one another without pause, like a tireless metronome. Stops are brief, passengers numerous, flows constant. One might think half the city converges here, between shopfronts, tram stops, fragments of conversation, and the scents of cooking. | |

|

|

| Very nearby, particularly along Gerberstrasse, shops and restaurants unfold in joyful abundance. Everything can be found here, for every taste and in every language. Basel asserts itself here as Switzerland’s most cosmopolitan city, perhaps even more so than Geneva. Every day, nearly one hundred thousand cross-border workers from France and Germany converge on the city, particularly to work in laboratories and headquarters of Swiss pharmaceutical giants such as Roche and Novartis. | |

|

|

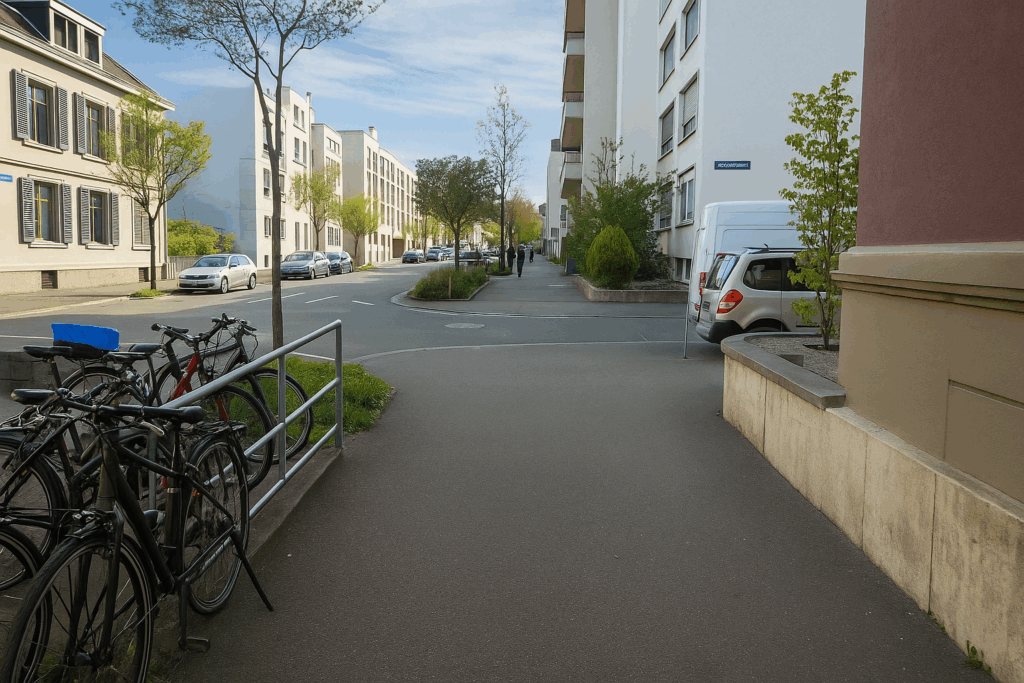

| Just below Leonhardkirche, on this hill climbed by the Basel Variant toward France, the itinerary that you will soon follow, a multitude of narrow and winding streets cling to the slope. | |

|

|

|

|

| Here too, the houses bear marks, dates, names—often in Gothic lettering that seems itself carved out of time. The shutters, painted a deep red or a bottle green, add to this painterly impression. Here, everything seems intent on asserting an identity, a distinctiveness. The past is not frozen; it still pulses in the details. This is where the stroll through the heart of old Basel comes to an end. | |

|

|

If you feel like continuing on toward the station, you are free to return there on another detour. As for you, your gaze now turns westward, for that is where your first stage leads.

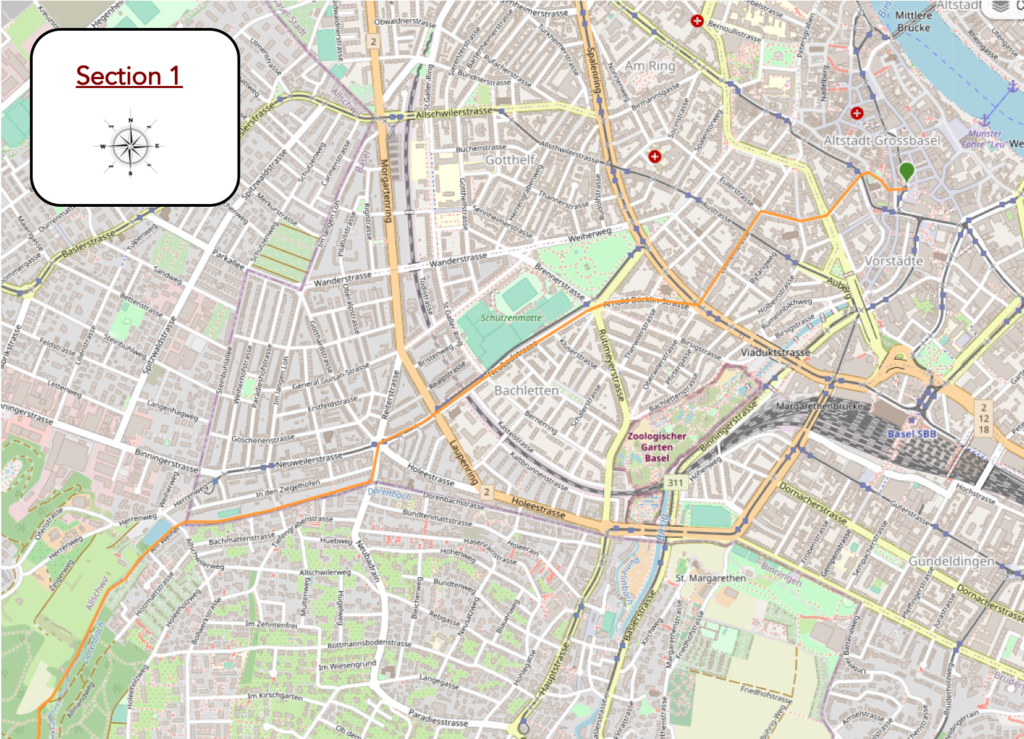

Section 1: The long crossing of western Basel

Overview of the route’s challenges: a route without major difficulty, with a few slopes in wooded areas.

|

Today, you set out from the very centre of the city, at Barfüsserplatz. At the corner of the square, near Gerberstrasse, a narrow alley opens discreetly, almost timidly. This is Lohnhofgässlein. It then rises via steep steps toward the esplanade overlooking the historic centre, where Leonhardskirche stands. This is where the city’s French-speaking church is located, a Gothic-inspired building dating from the sixteenth century. In Basel, bilingualism is claimed, yet here, in the streets or on public benches, French remains discreet, like a muted murmur. . |

|

|

|

|

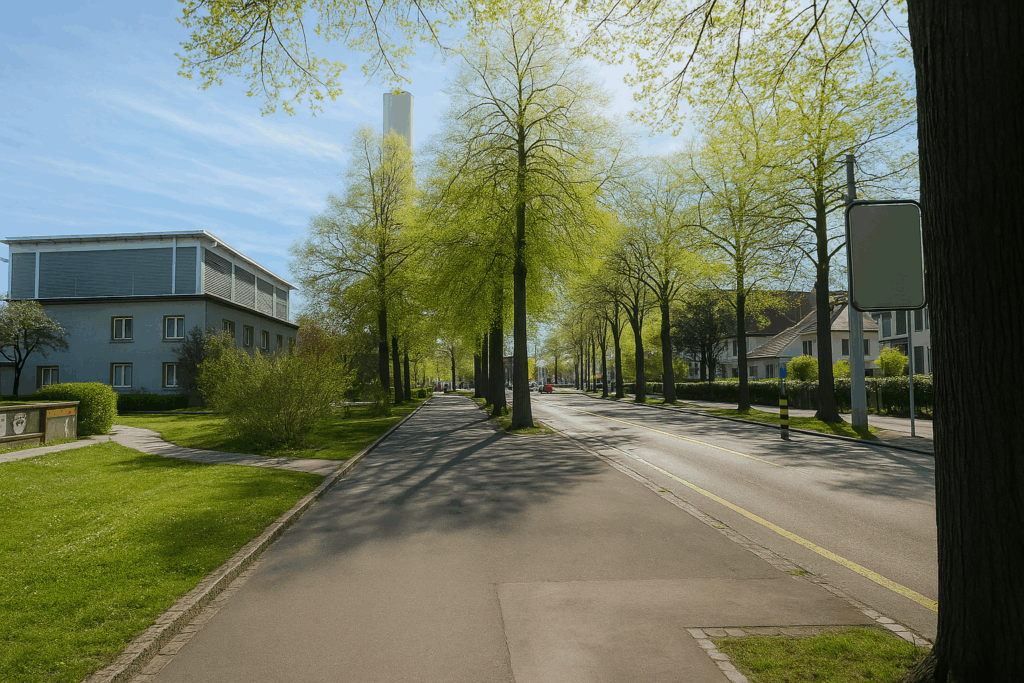

Not far from the Music Academy, the route leads you across the tram tracks, those long mechanical serpents that crisscross the city, before guiding you into Leonhardsstrasse. You slip along it like through a corridor, punctuated by successive intersections, each one marking a brief pause in the progression. |

|

|

|

|

At the end of Leonhardsstrasse, a gentle curve to the left brings you onto Leimenstrasse. There, at the turn of the street, rises the Basel synagogue, majestic in its restraint. This late nineteenth-century building affirms, through its presence, the city’s religious diversity and cultural richness. |

|

|

|

|

Leimenstrasse cuts through the urban fabric, crosses several main arteries, and comes up against the inner ring of the city, the Steinenring. A form of boundary, flexible yet clearly defined, between the old heart and the modern rings. |

|

|

|

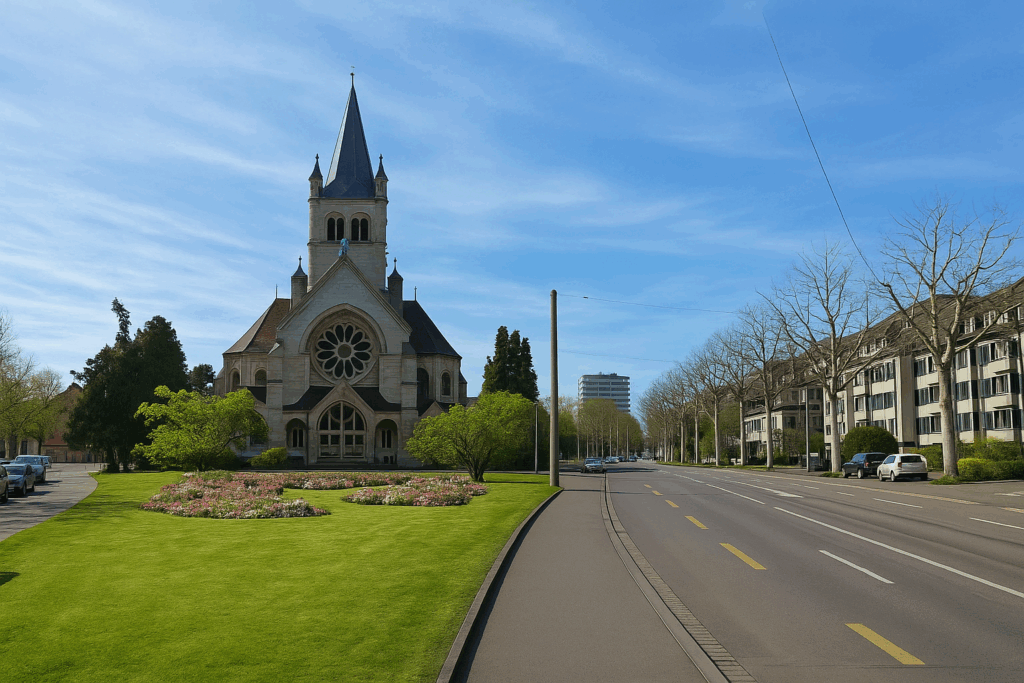

| Further on, Arnold Böcklin-Strasse curves softly and leads you past Pauluskirche. This Protestant church, in neoclassical style, was built in the early twentieth century. It stands there with imposing serenity. A high place of sacred music, it frequently hosts concerts where architecture seems to respond fervently to the notes. | |

|

|

| Arnold Böcklin-Strasse ends at Bundesplatz, State Square, like a threshold before another world. From there, the Basel connector aligns itself with Neubadstrasse, a long, almost stubborn axis that you will follow for quite some time. | |

|

|

| Along Neubadstrasse, tramways and buses share their trajectory with surprising ease. On your right, your gaze is drawn to Schützenmatte, a sports field. | |

|

|

| Near the modern Catholic church, Allerheiligen Kirche, the Church of All Saints, the connector crosses the Laupenring. The landscape shifts at Neuweilerplatz, for here the city seems to breathe again. Social life resurfaces, with shops, café terraces, and a calm flow of passersby. After so many nearly deserted streets, the place vibrates once more with human presence. | |

|

|

| It is at Neuweilerplatz that you leave the city centre for good. Another hundred meters along Neubadstrasse, and you reach the entrance to Dornbach-Promenade. The tone changes. Here, the bustle fades. The promenade slips into a gentler, more vegetal world. The Dornbach stream barely snakes along, as if it wished to pass unnoticed. Beneath tall trees, elegant footbridges link the banks, and patrician houses take on a countryside air. | |

|

|

|

|

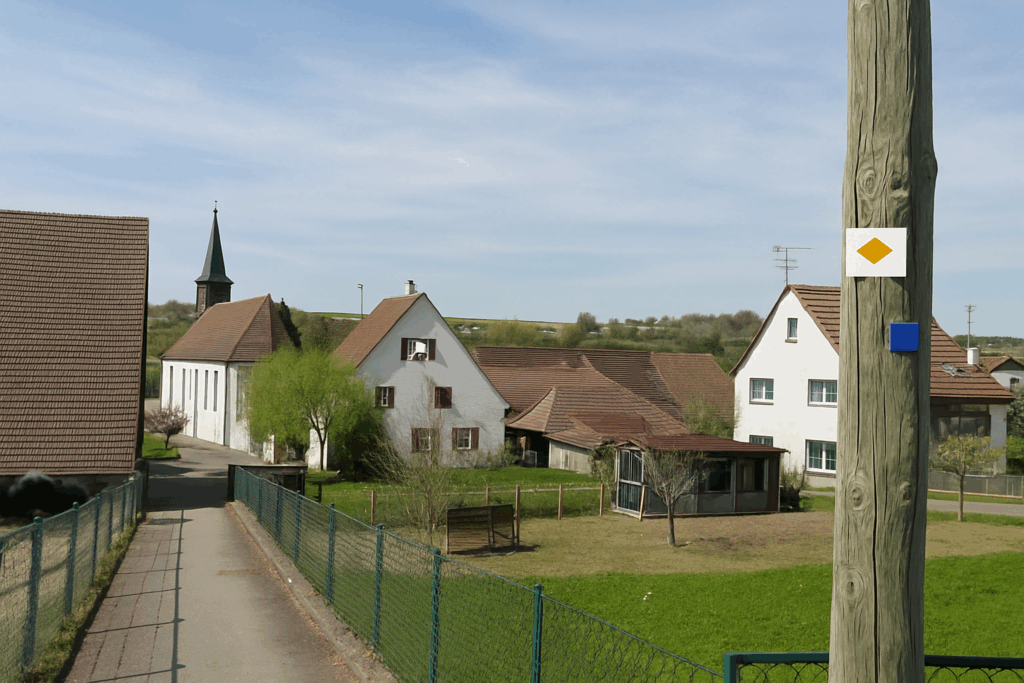

You then arrive at Am Weiher, a name that carries the scent of peace. Here converge the signs of Via Jura Regio 41, which also leads to Ferrette. But do not be mistaken. If Swiss signposting is of an almost poetic subtlety, once the border is crossed, it vanishes. Only local markings remain in France, those yellow diamonds that guide hikers along the paths. At this spot, a sign simply announces the distance. Ferrette lies more than six hours away on foot. The adventure takes shape.

| The promenade stretches on a little further along the Dornbach stream, then skirts the small, tranquil Weiher lake. A path remains faithful, linear yet never monotonous. | |

|

|

| You then walk alongside a shooting range, set there like an anachronistic wink. | |

|

|

| Further on, the path crosses the road of Sunday gardeners. Another world opens up, that of neatly aligned vegetable plots, brightly painted sheds, watering cans, and hopes rooted in the soil. | |

|

|

| The promenade then plays with the stream, shifting from one bank to the other, as if testing its moods. In this wide space, where walls are covered with colourful graffiti, families settle in, and shouts and laughter rise like a chorus. It is an open-air theatre, a place of life that breathes deeply on weekends and public holidays. | |

|

|

|

|

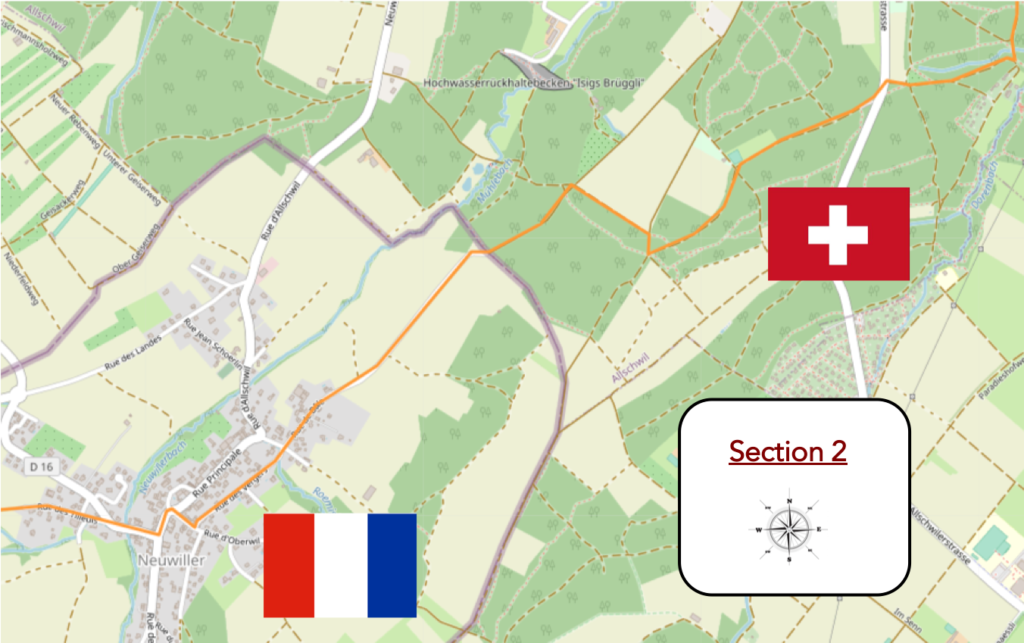

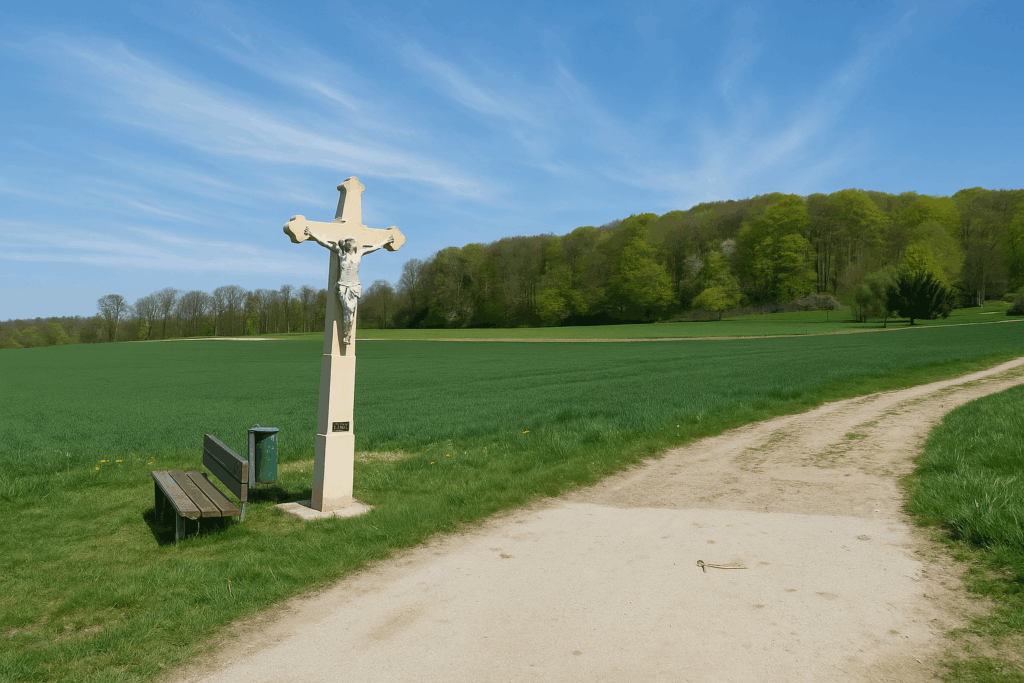

Section 2: Crossing the border

Overview of the route’s challenges: a route with no difficulty.

| Then a wide dirt path slowly moves away from the stream and gains altitude, entering the undergrowth. Here, light filters through the canopy of beech trees, noble and immense, which dominate the landscape. A few oaks with massive trunks stand guard in silence, while spruces, more austere, cluster their dark silhouettes in the depths of the forest. | |

|

|

| But it is indeed the beech, this giant with pale foliage and a trunk smooth as soft stone, that reigns here as master. In low-altitude forests in Switzerland, it imposes its calm and reassuring presence. | |

|

|

You move forward beneath these high natural vaults, in the Unterlangholz forest, to the rhythm of your footsteps on the springy ground. The silence is barely disturbed by a few birdsongs.

| Soon, a picnic area appears in a clearing. It seems to emerge straight out of a Swiss urban planning handbook, with a stone barbecue, solid wooden benches, and logs stacked with care. Here, however, there is no axe or matches provided, which would not have been surprising in German-speaking Switzerland, where one sometimes even finds dry kindling ready for use. | |

|

|

| The path continues its way and reaches Oberwilerstrasse, a departmental road that crosses the forest almost timidly, without breaking the harmony of the place. A glance at the signs still reveals the famous yellow diamonds. These are those of the Via Jura, restrained and reliable. In Switzerland, main paths are always marked with these large yellow diamonds, faithful guides for hikers. | |

|

|

| From there, a broad forest avenue resumes its course toward the countryside. The ground, perfectly compacted, is so even that one forgets it is made of packed earth. No gravel catches the sole. This likely exists nowhere else. You understand why walkers, joggers, Nordic walkers, and dog owners with leashes tread it daily with such consistency. It is a breath of air. | |

|

|

| At the place known as Breiti Hurst, the road skirts a sunlit clearing before plunging once more into woodland coolness. | |

|

|

| In this open, limpid forest, the tree trunks stand spaced apart like elements in a painting. Space itself seems to breathe. Here, everyone finds a place, families with strollers, solitary hikers, friends gathering for lunch on the grass. Nature feels welcoming, almost tamed, without losing any of its beauty. | |

|

|

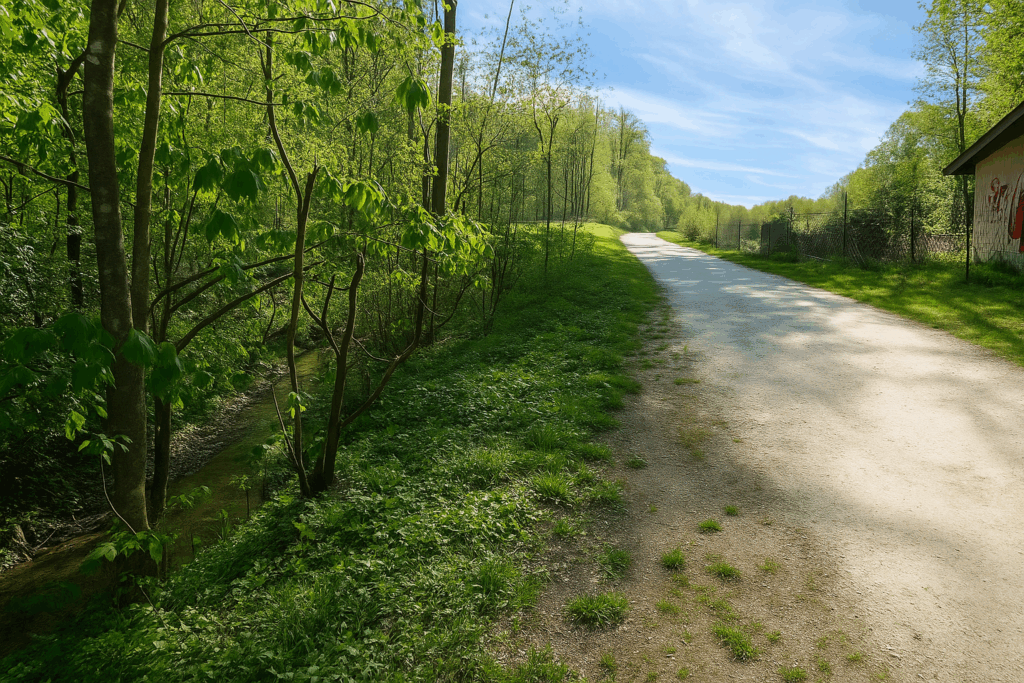

And then, at the place called Chuestelli, a symbolic turning point arrives. It is here, for the last time, that you encounter a Swiss hiking sign. These small yellow totems, as bright as a field of chanterelles at the end of summer, are about to vanish. You enter another world. Soon, the markings will be French, with squares, triangles, and diamonds of every colour, following the shifting logic specific to the paths of Alsace or Franche-Comté. The contrast will be felt.

Neuwiller, the first French village on the route, is now only half an hour away on foot. A border is about to be crossed, not only geographical but also cultural.

| Here, you are very close to the frontier. The path runs alongside a vast, peaceful clearing, where tall grasses ripple gently in the wind. At the forest edge, the place name Ziegelhof appears on maps, yet nothing indicates that you are already almost on borderland territory. | |

|

|

| One last short stretch of forest remains. The ground becomes slightly looser, the foliage thins. And there is the border. No sign, no barrier, and certainly no customs officer. The crossing happens smoothly, almost without the walker noticing. | |

|

|

| On the other side, a small paved road, straight and orderly, begins to descend gently between fields. The Alsatian countryside opens before you, softly rolling, edged with hedges and light woodland. | |

|

|

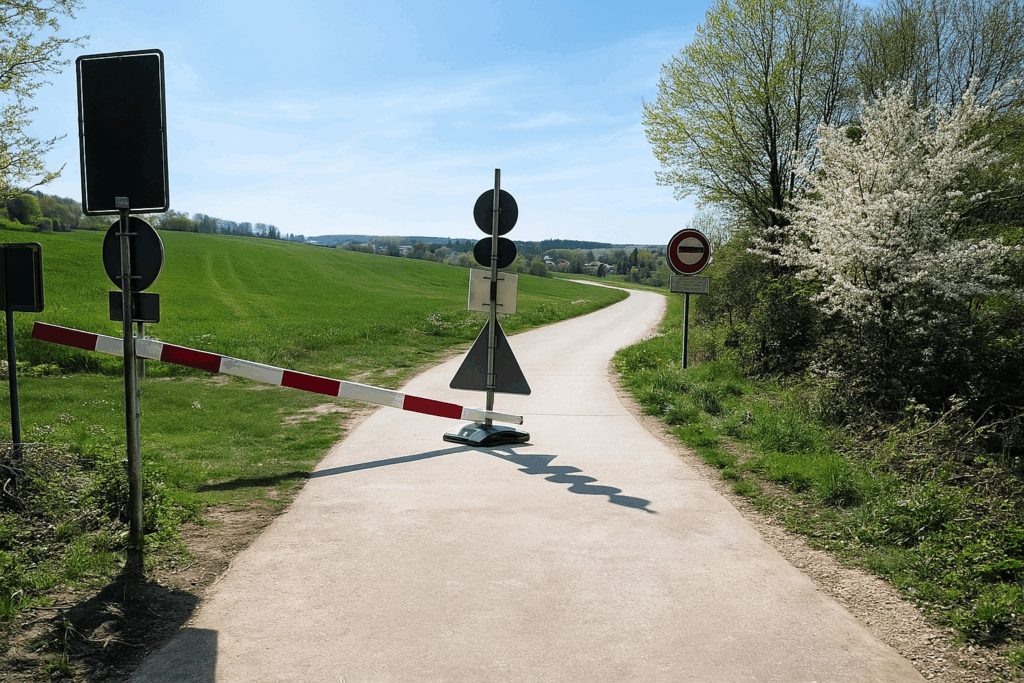

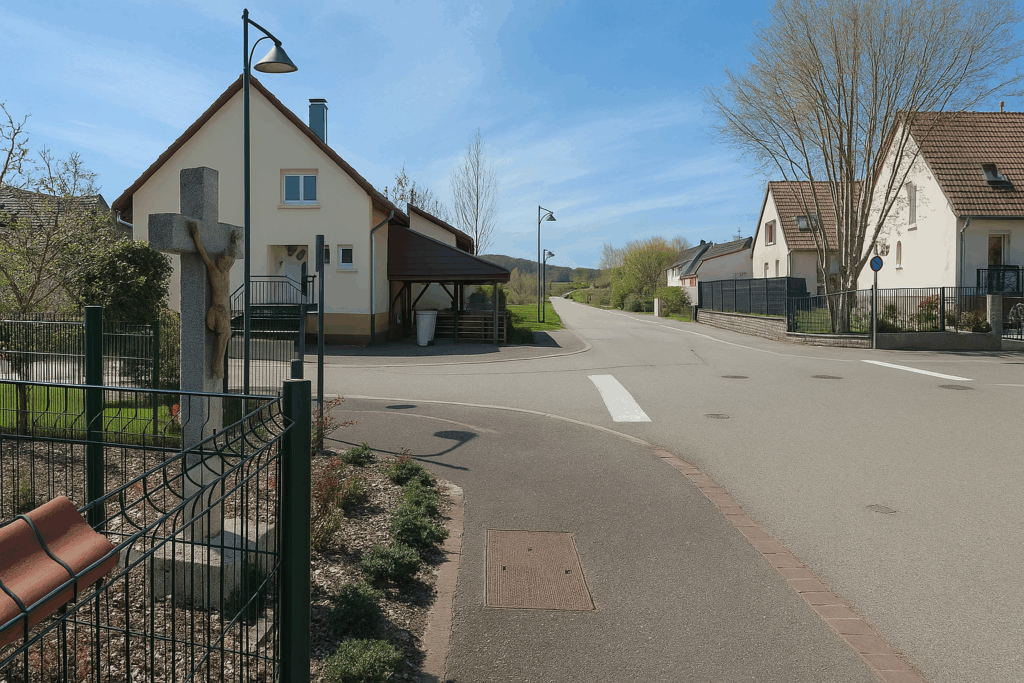

| In this region, stone crosses are numerous. Witnesses to an ancient and deeply rooted faith, they punctuate paths and crossroads alike. Soon after, the road reaches the first houses of Neuwiller, a quiet and neat French village. | |

|

|

| The road crosses the village at an unhurried pace. Another cross rises at the edge of a garden, and more surprisingly, a Chinese garden, carefully arranged, offers itself to the curious eye. | |

|

|

| The road passes near the church, then gently descends into the heart of the village. Here, French signage takes over. Markings are small yellow diamonds, often discreet, sometimes absent. One must keep a sharp eye, or better yet, a travel guide. Otherwise, it is easy to go in circles. | |

|

|

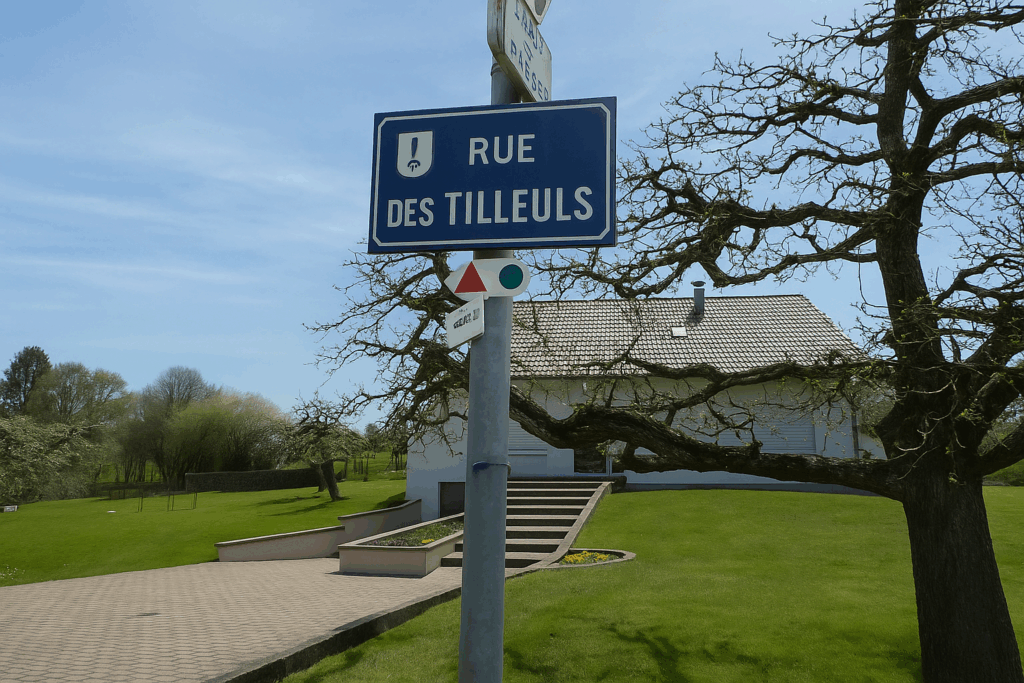

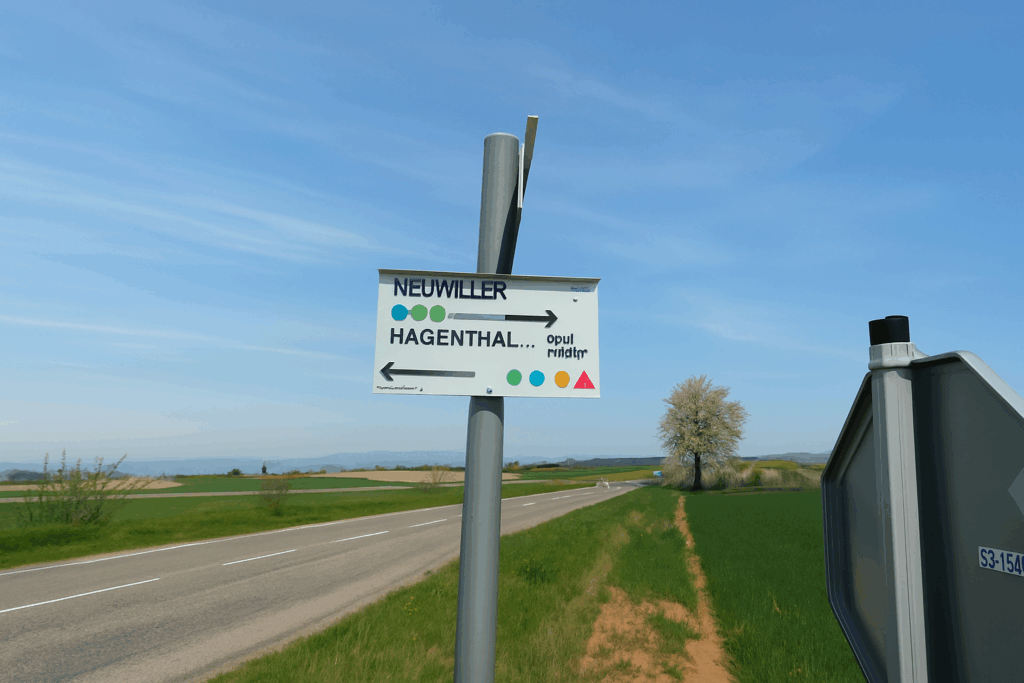

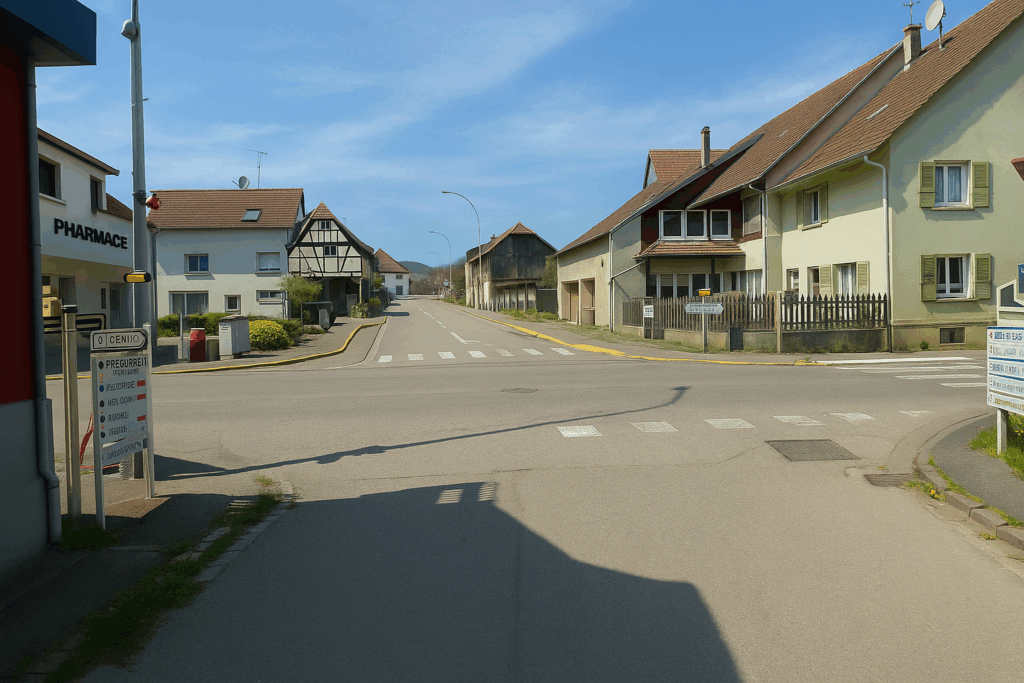

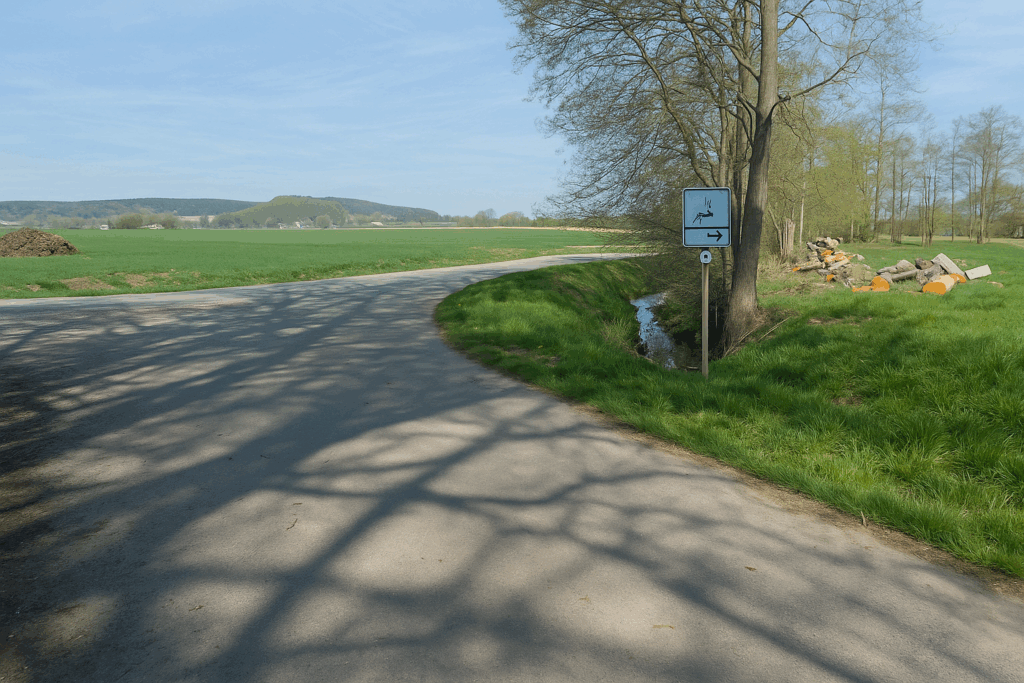

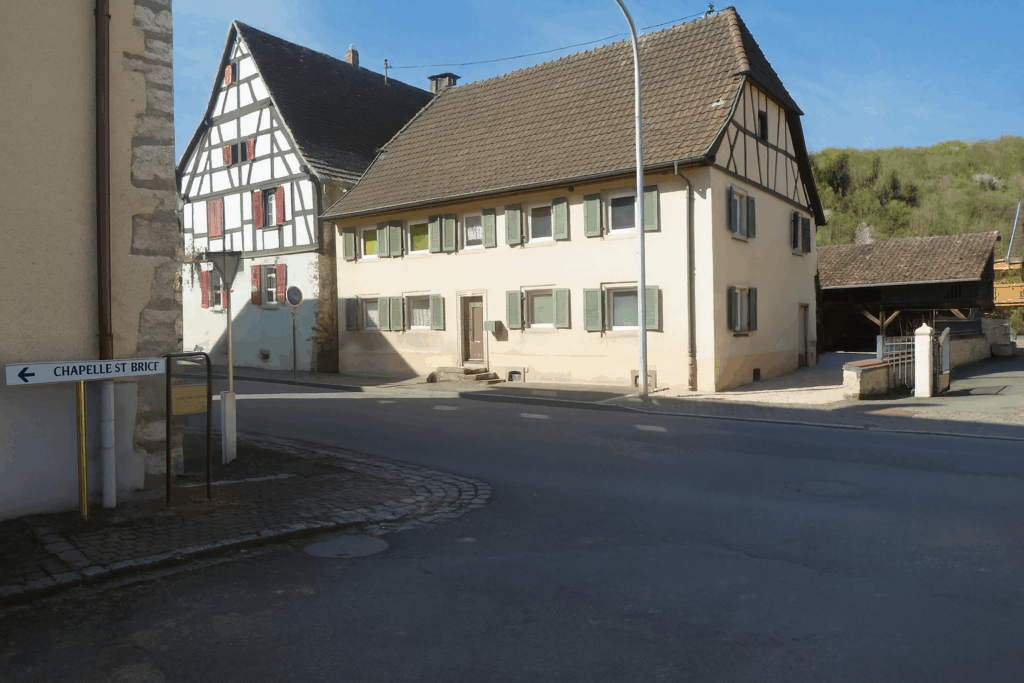

| A little further on, after Rue des Vergers, a directional sign appears that borders on surrealism. It displays more directions than there are passersby in the street. Arrows, pictograms, varied colour codes, it seems that the entire universe converges at that point. Between yellow diamonds heading in two opposite directions, red triangles, and green dots, the walker hesitates. You must trust Via Jura Regio 41, the small Compostela shell sometimes affixed to a post, and know that Hagenthal-le-Bas is the next stage. Otherwise, you might remain frozen there, like before a riddle without a solution. | |

|

|

| When crossing the Neuwillerbach stream, a new rule applies. The yellow diamonds are finished, replaced by red triangles. And the green dots? They are there, mute, without explanation, like a foreign language for which no dictionary has been provided. You must manage, trust instinct or the memory of paths. For too much information, without guidance, can become more disorienting than the absence of all markers. | |

|

|

Section 3: From one village to the next

Overview of the route’s challenges: a few slopes without real difficulty.

|

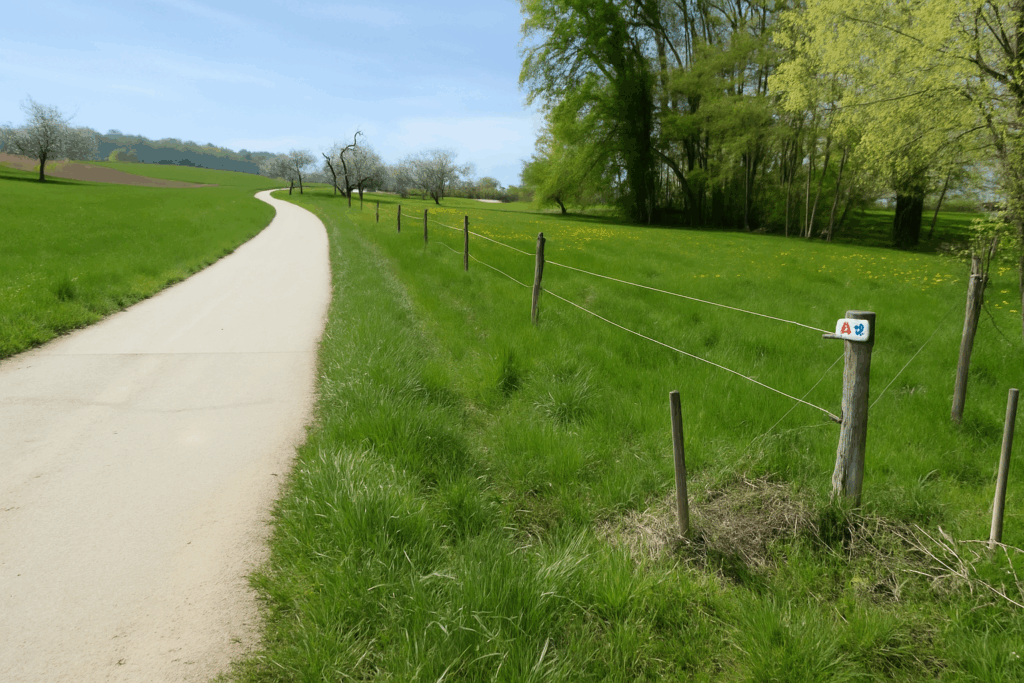

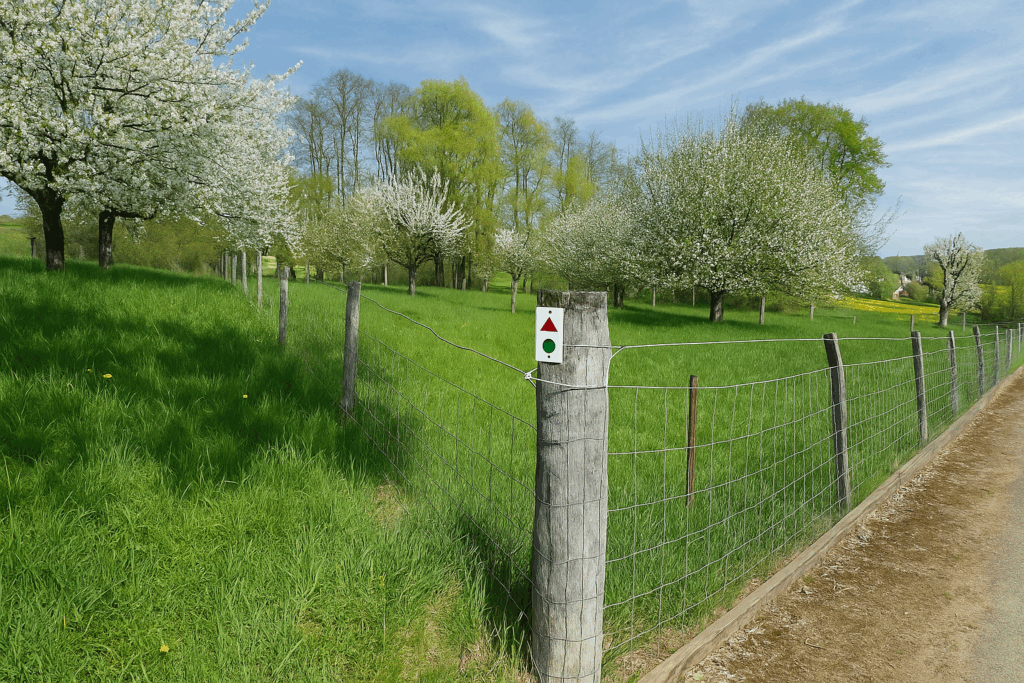

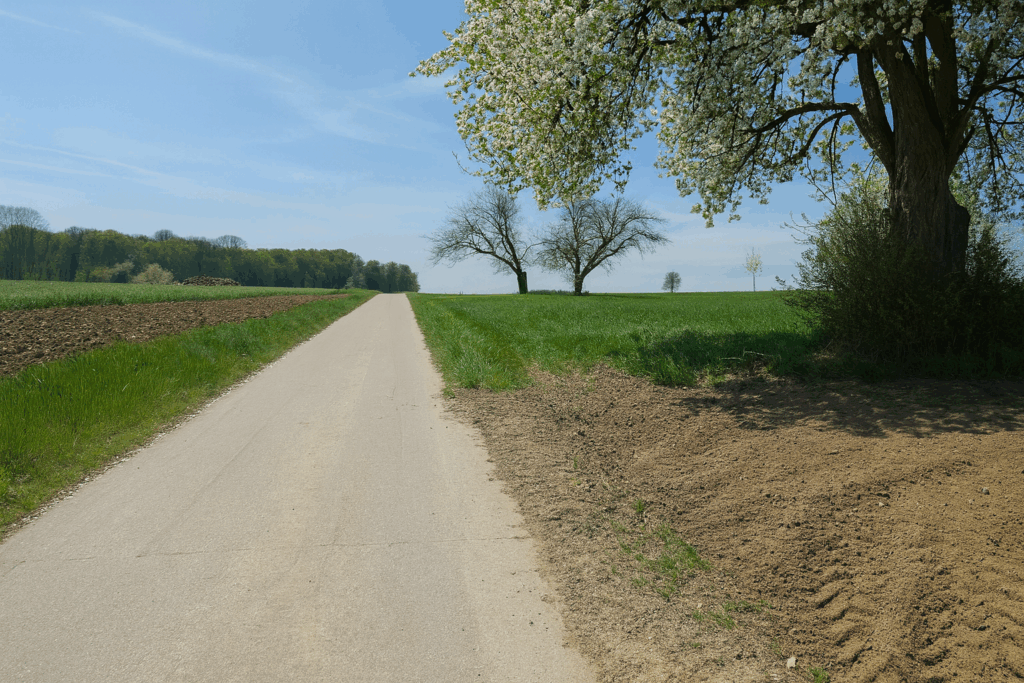

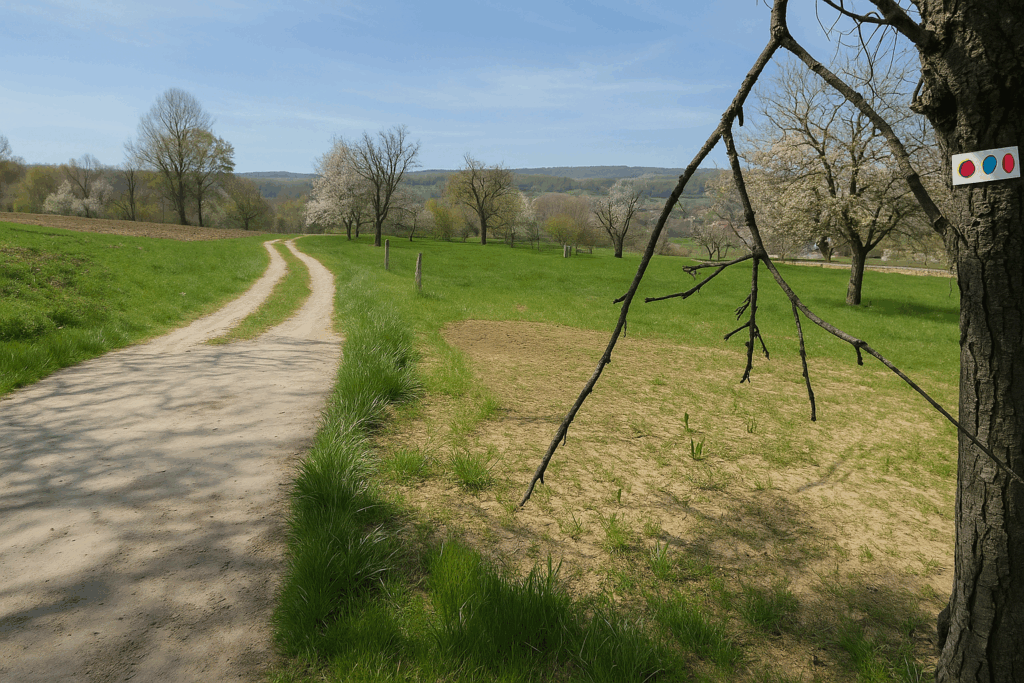

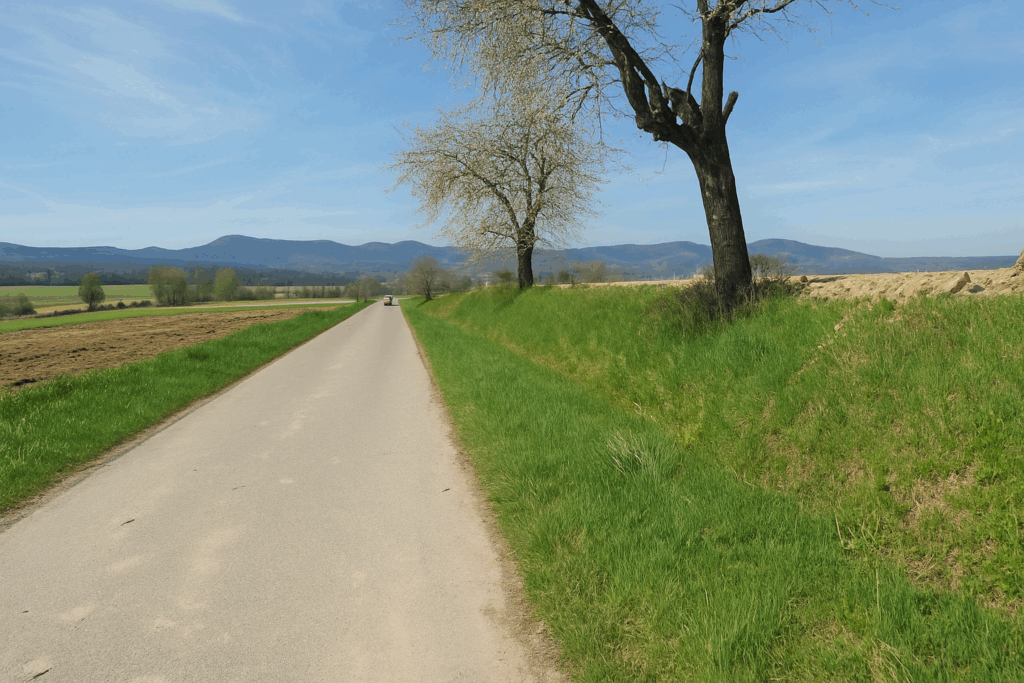

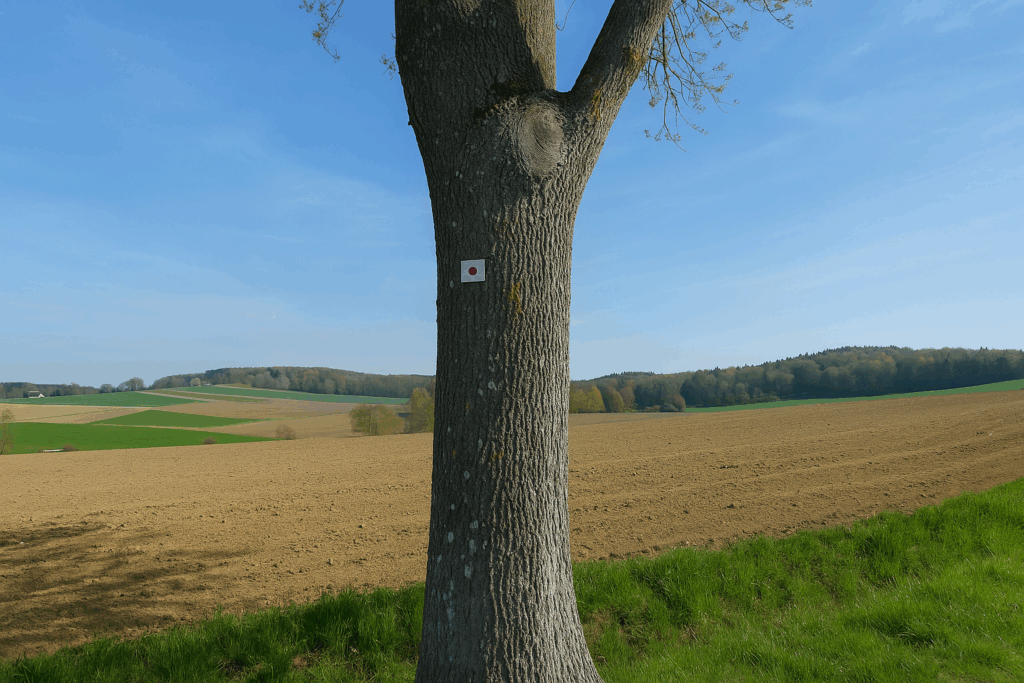

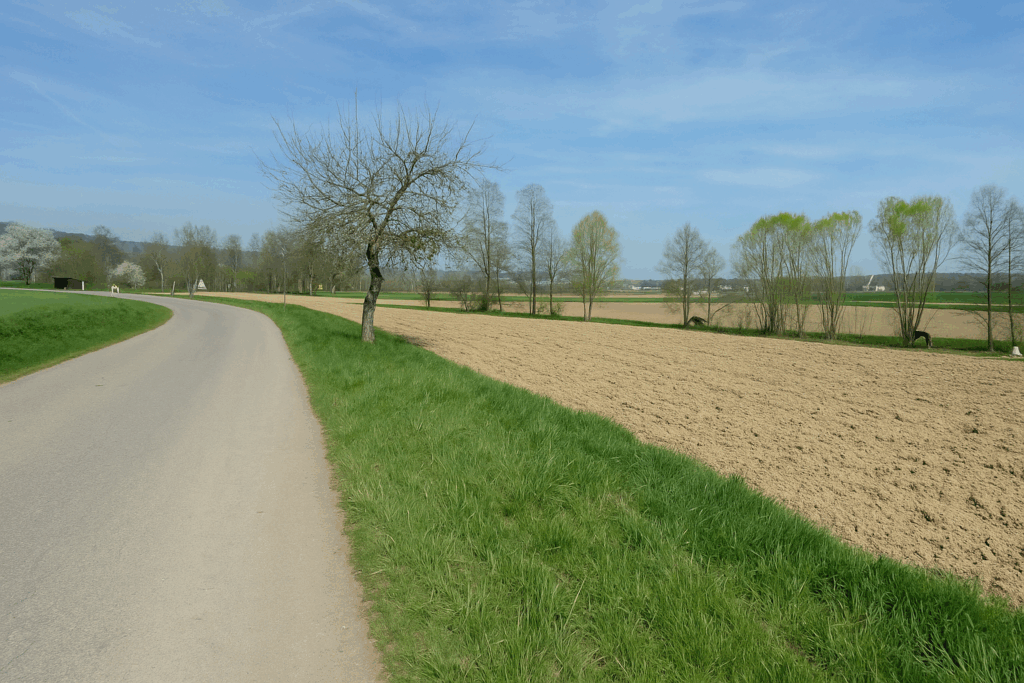

The route leaves Neuwiller via Rue des Tilleuls. It slopes up gently, without any real difficulty, along a small country road bordered by meadows and fields. The markings continue, red triangles and green dots. But by focusing too much on watching the signs, one forgets to lift one’s eyes to admire the landscape. That is a pity, is it not ? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

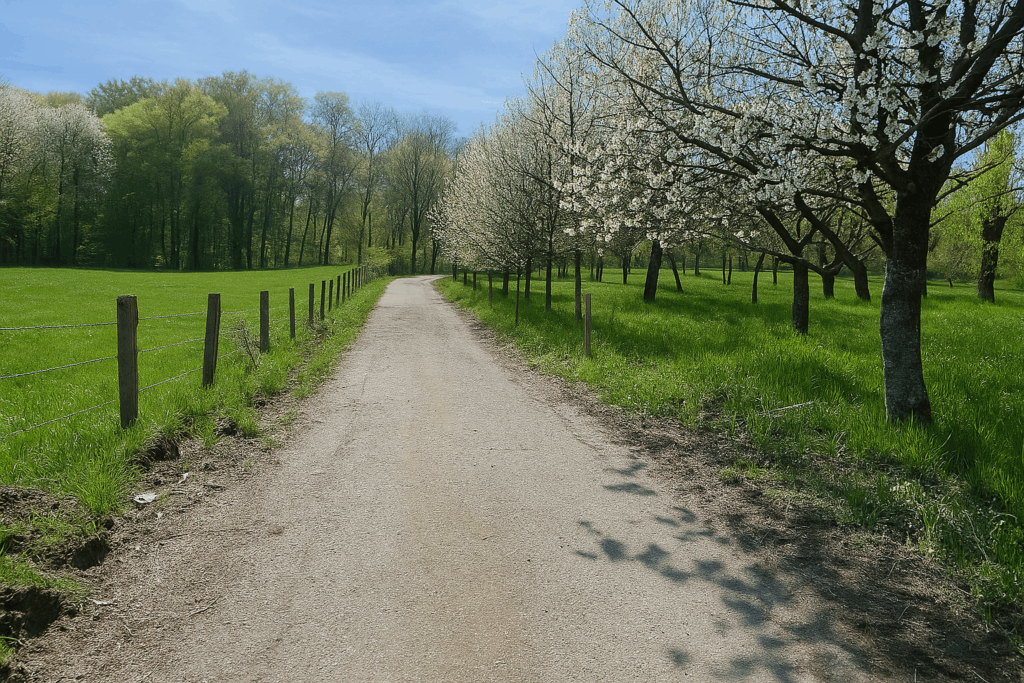

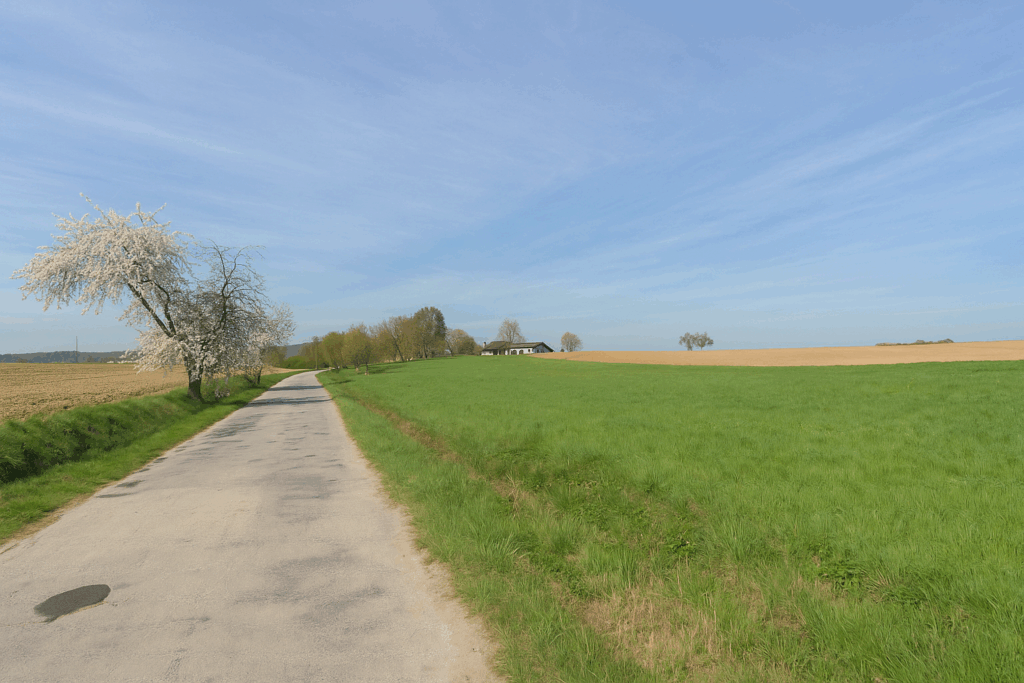

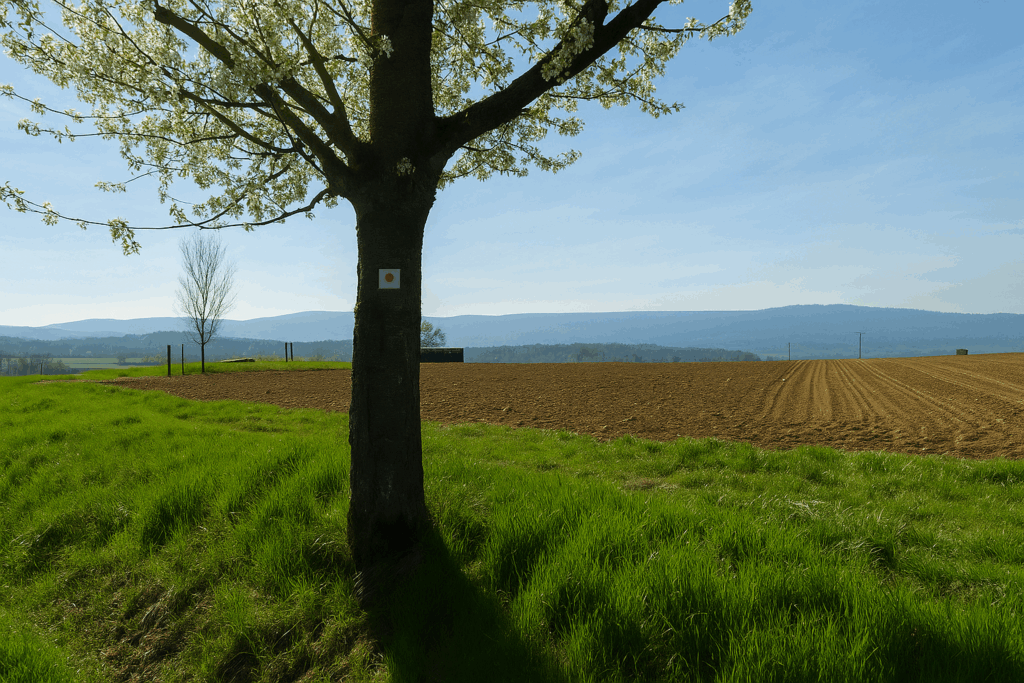

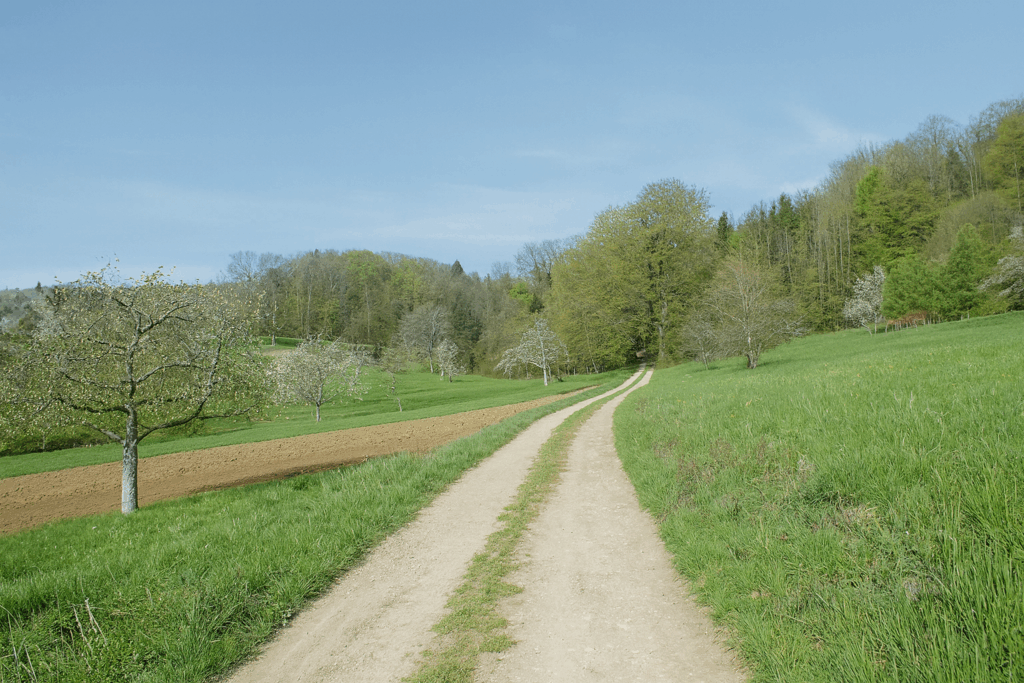

When we passed through here, fruit trees were in bloom. A gentle spring countryside, discreet yet vibrant. |

|

|

|

| The climb stretches on, steady but long, until it meets the much busier departmental road D16. | |

|

|

|

From there, the view opens onto the village of Hagenthal-le-Bas below. But the game of markings continues. At this junction, a red circle and an orange circle have been added. Why not? But for whom? That remains a mystery. Yellow circles are often intended for equestrian circuits. The green dot will likely remain without explanation, unless a local scholar reveals its secret to you. As for the red dot, who can say. Perhaps a variant for the undecided? |

|

|

|

|

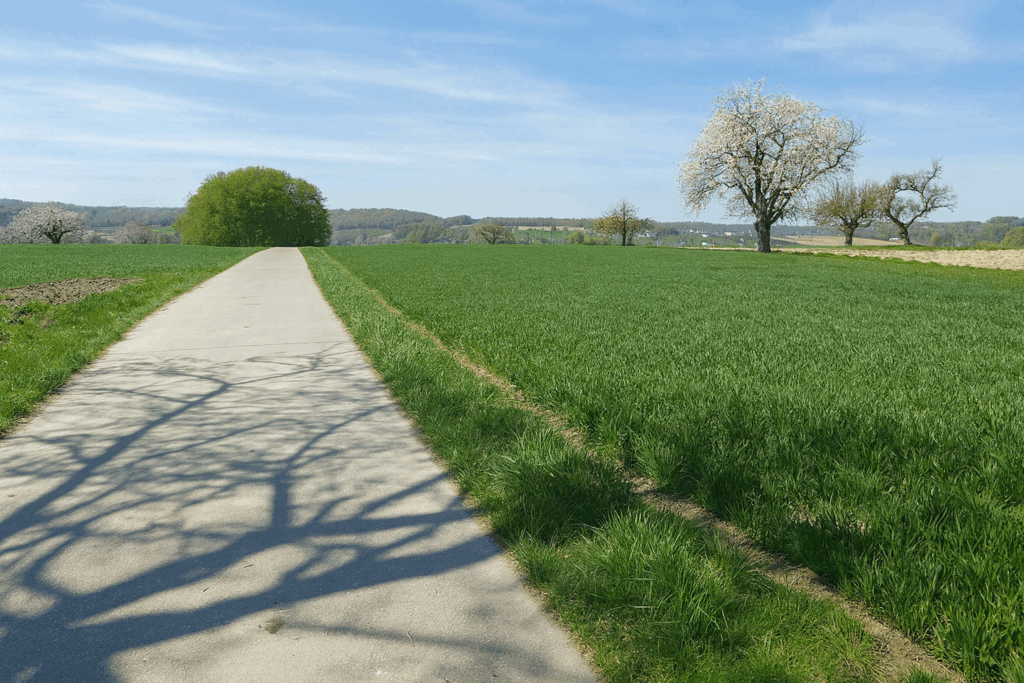

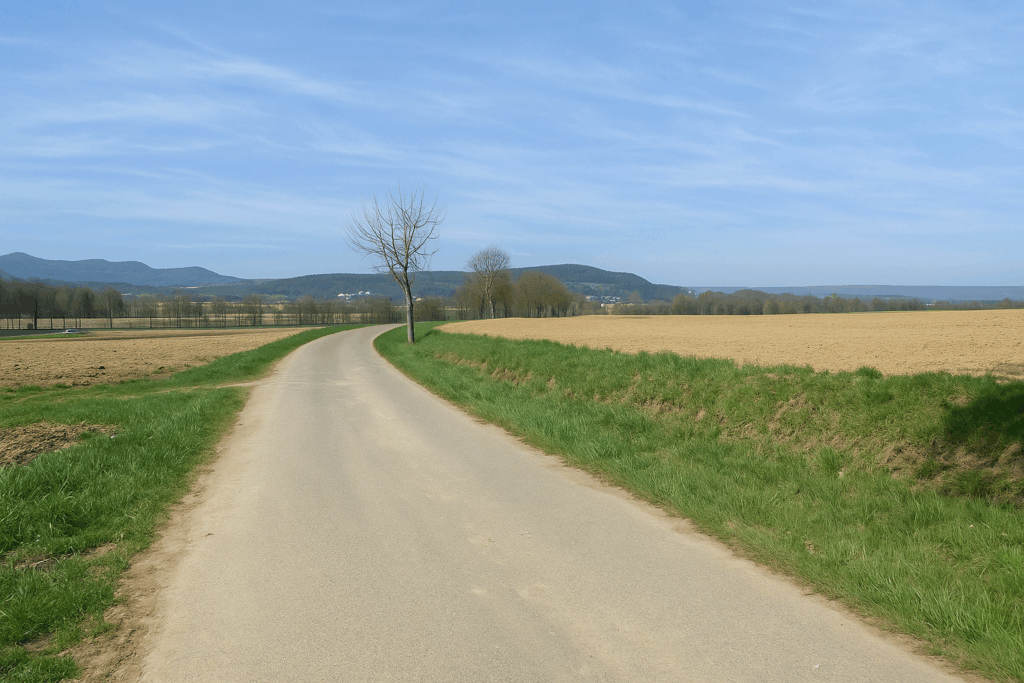

The road now descends through wide open fields. The sky feels broader here. The eye ranges far beyond the ploughed furrows. |

|

|

|

|

The slope becomes steeper at times. As the village approaches, a section of dirt track suddenly replaces the cement, with no obvious reason. Then the asphalted road resumes its role, as if nothing had happened. |

|

|

|

|

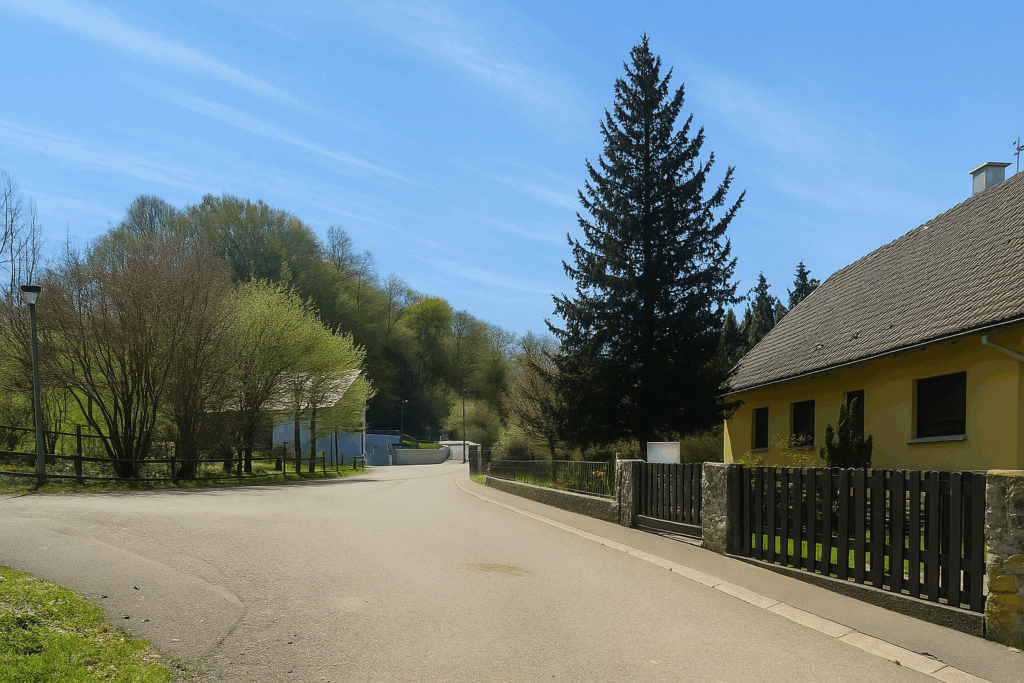

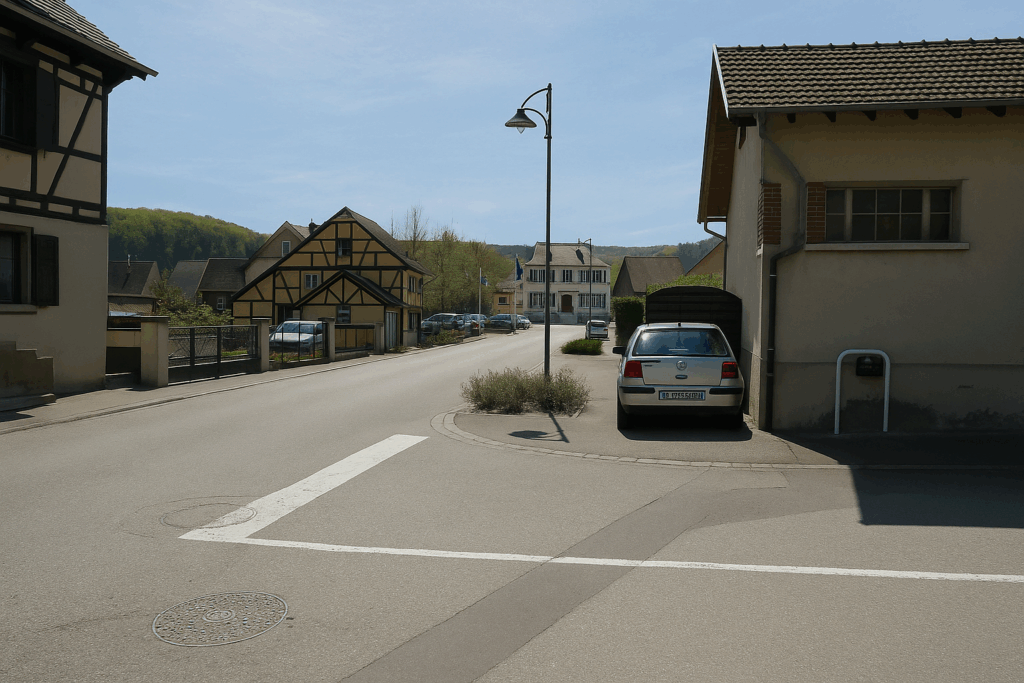

At the bottom of the descent, hidden behind a hedge of ash trees and a few dark birches, the road gently enters the outskirts of Hagenthal-le-Bas. The village is quiet, the houses neatly aligned, shutters often closed at this calm hour of the day. |

|

|

|

|

You will have to accept it, but you will not be able to form a clear conclusion. Here, the red triangles are over. In their place now appear blue rectangles, arriving from another path coming from the north. Fortunately, the Via Jura 41 signs and the Compostela shells are still there to guide you. For further on, on the signposts, the names of the villages you will cross today are striking by their absence. We have nothing against our hiking friends from Alsace. But still, the path of Santiago matters a little, does it not? It seems very discreet here. The outsider, if not equipped with a guide or a GPS, is quite likely to go around in circles. By contrast, the locals know these paths by heart. They need no directions nor markings to go where they intend. |

|

|

|

|

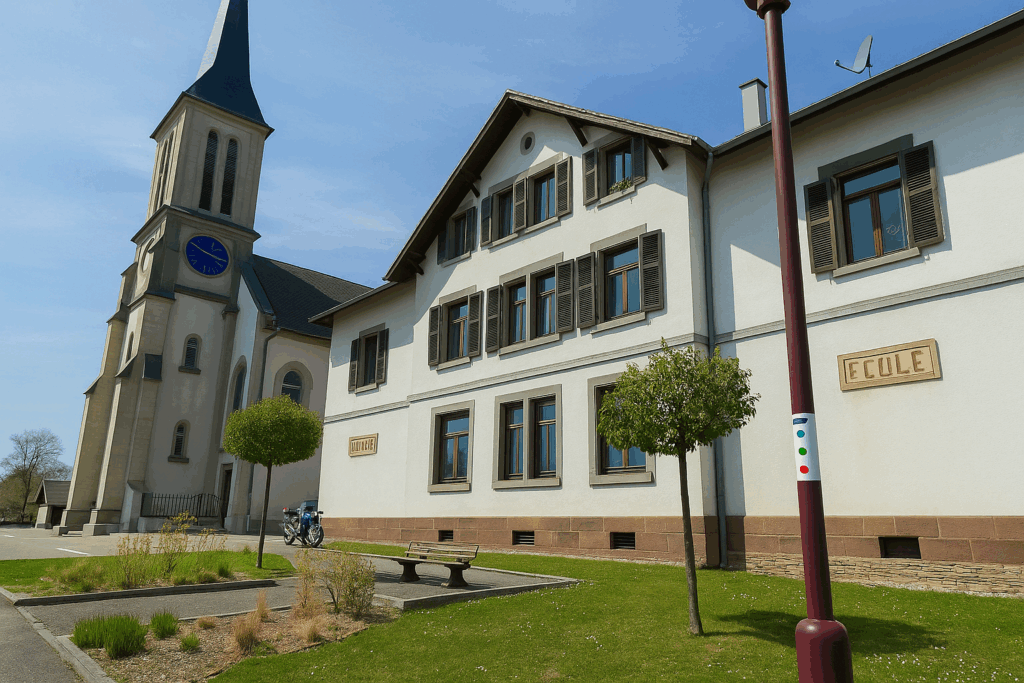

The road continues calmly through Hagenthal-le-Bas. It passes by the school, then by the village church, simple and well maintained. |

|

|

|

|

Here again, numerous stone crosses punctuate the route, witnesses to a tradition still very much alive. |

|

|

|

|

Climb the road a little. And in this true jumble of directions, choose the one that leads to Hagenthal-le-Haut. Somewhere, between two posts, the blue rectangles reappear. You will never know exactly where one of the two Hagenthals begins, nor where the other ends. But that hardly matters. |

|

|

|

|

The road runs in front of the town hall, an imposing building with the air of a small prefecture, contrasting with the more modest surrounding houses. Then it continues on through the rest of the village. |

|

|

|

|

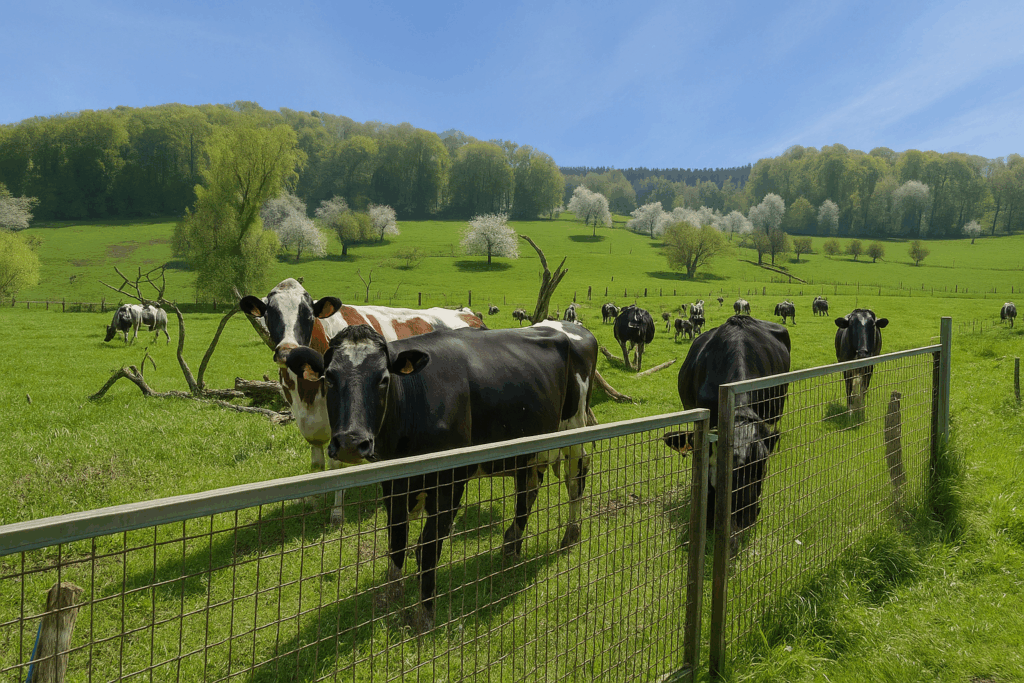

At last, the crossing of the two Hagenthals comes to an end. The road moves away. In the surrounding fields, cows barely raise their heads, surprised to see these pilgrims with large packs and dusty shoes pass by. |

|

|

|

Section 4: A vast forest to cross

Overview of the route’s challenges: more demanding slopes within the forest.

|

From here on, it is forest almost without interruption all the way to Ferrette. You were clearly told to follow the blue rectangles. So, you search the trees, the posts, the rocks. At first, nothing appears. As you leave the village, a small road that quickly turns into a dirt path heads toward the forest. |

|

|

|

|

There, in the heart of this vast forest, beech trees still reign supreme. They raise their smooth, grey trunks toward the sky, forming an elegant vault. |

|

|

|

|

And then, a few hundred meters further on, at last some good news. A blue rectangle, clear and visible, fixed to a large beech tree. A sigh of relief. You are on the right way. For the green dots, if they are meant for cyclists, not a single one has been seen so far today. |

|

|

|

|

But do not celebrate too quickly. Further on, you come across a direction sign. Doubt sets in. No one warned you that you would have to abandon the blue rectangles that head toward Leymen. Do you go via Leymen? Nothing is less certain. The route, as often happens, splits in two. And no sign tells you that you must now follow the yellow diamonds. So, what is to be done? There is only one solution on the Basel connector. You must have prepared your journey seriously, with accurate maps or a reliable guide. The small book entitled Le Chemin de Compostelle en Alsace, Franche-Comté et Bourgogne, even if sometimes brief, remains the only one that truly describes this route. It explains clearly, for those who reread it afterward: “At the exit of the village, follow the blue rectangles. Climb on asphalt through fields, then enter the forest along a stony path. Then, at a junction of paths at the top of the hill, follow the yellow diamonds again.” Fortunately, the ever-methodical Swiss have left one more Via Jura 41 indication to reassure you. But here, this is no minor matter. In this vast and deep forest, if you head off in the wrong direction, you risk wandering for a long time. There is now only one reflex to adopt: look for the yellow diamonds. |

|

|

|

|

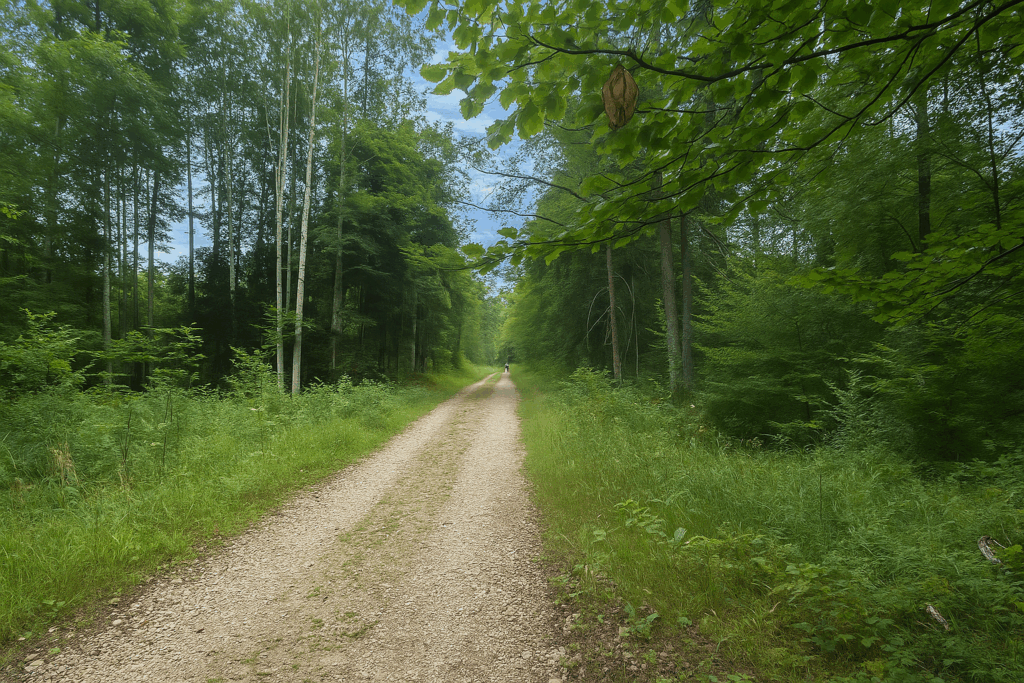

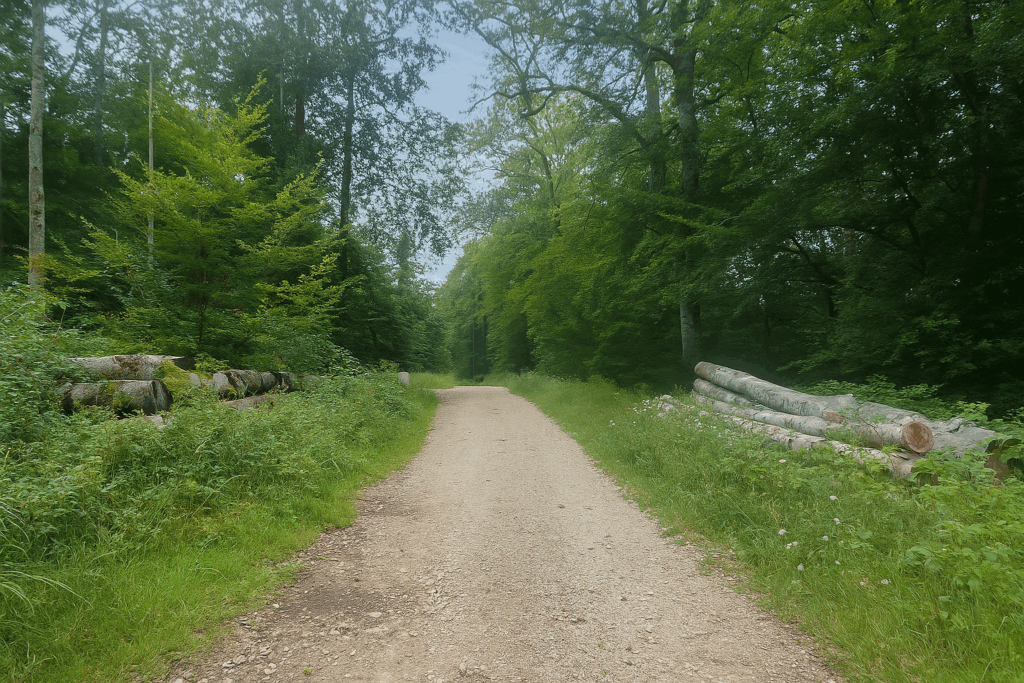

Fortunately, the forest is magnificent, airy, alive. You encounter the traces of forestry tractors. The wood is worked, yes, but without brutality. The paths remain clean, wide, and pleasant. |

|

|

|

|

You walk on, attentive to the slightest marking. Here, a yellow diamond on an oak. There, another painted directly onto the bark of a beech. Each marking reassures you, like a complicit blink from the path itself. |

|

|

|

|

Then, a little further on, you remember what the guide says: “When the markings invite you to leave the wide path for a trail opposite, with steep and muddy sections, stay on the path to the right and continue without markings in order to rediscover the usual markings after a short climb.” Easy to say when one already knows the terrain. But here, before you, several paths intersect, slant diagonally, descend, climb. The markings suggest turning off, but you hesitate. The guide advises not to follow them. Advice of this kind only becomes useful once the route has already been walked. Never take unmarked shortcuts, your common sense tells you. And yet this trail narrows and begins to climb. Let us go and see where it leads. |

|

|

|

|

The slopes in the Wessenberg forest are demanding, often between 15 and 25 percent, over more than a kilometre. The ascent is sustained, but rewarding. The forest is superb and majestic, with its tall beech trees and sturdy oaks of all sizes, growing from a thick carpet of last season’s fallen leaves. At times, small stone markers emerge, covered in moss, remnants of former boundaries whose function has now been forgotten. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The higher you climb, the steeper the slope becomes, and the more modest the beech trees appear, sometimes reduced to young shoots, straight as stakes, pressed close together as if to protect one another from the highland wind. |

|

|

|

|

And then, suddenly, a yellow diamond reappears, marked on a stocky oak. Relief. You meet a mountain biker racing downhill at full speed and ask for confirmation. Yes, this is indeed the right path. That small yellow diamond, insignificant to many, is a blessing for the walker. For turning back after several kilometres when one has taken a wrong turn is the kind of thing that crushes morale more surely than an icy downpour. |

|

|

|

|

The descent then begins, gentle at first, through a forest that is still just as splendid. As altitude is lost, the woodland becomes more open, the trees taller, and light filters through the foliage, bathing the trunks in a warm, diffused glow. |

|

|

|

|

The forest path then winds along the bottom of the hill, almost flat. In places, an old and curious boundary stone stands by the side of the path, as if forgotten there by a surveyor from another century. |

|

|

|

|

Then comes a muddy section, well known to walkers, where repeated tractor passages have carved deep ruts. Here, it is often wiser to follow the parallel tracks created by wild boar or previous hikers, who have traced drier alternatives through the undergrowth. |

|

|

|

At the end of this tricky zone, whose difficulty is easy to imagine after heavy rain, a welcome sign finally appears. St Brice is indicated. You breathe again. If you took the time to prepare your itinerary, you know this is the right direction. Better still, everything aligns here. Yellow diamonds, St James shells, Swiss Via Jura 41 markings, all point the same way. You move forward without hesitation.

|

The forest then changes name, even though it retains the same wild beauty. You leave Wessenberg and enter Britskiwald. The path continues almost flat for a while longer, then turns decisively toward the descent. . |

|

|

|

|

It is a marked slope, sometimes reaching 15 %, down toward the small departmental road D9b. You must place your feet carefully, especially on damp ground. |

|

|

|

|

You follow this road briefly, for just a few meters, before finding a path leading toward the chapel of St Brice. As always, the faithful yellow diamonds guide you, along with the Swiss symbols of Via Jura 41, reassuring companions on the route since Basel. |

|

|

|

Section 5: A chapel on the route and more beautiful forests to cross

Overview of the route’s challenges: downhill sections without real difficulty.

|

The path crosses the road, then climbs slightly again through ruts carved by forestry machinery. At times, you need to place your feet carefully, especially if rain has made the ground slippery. |

|

|

|

|

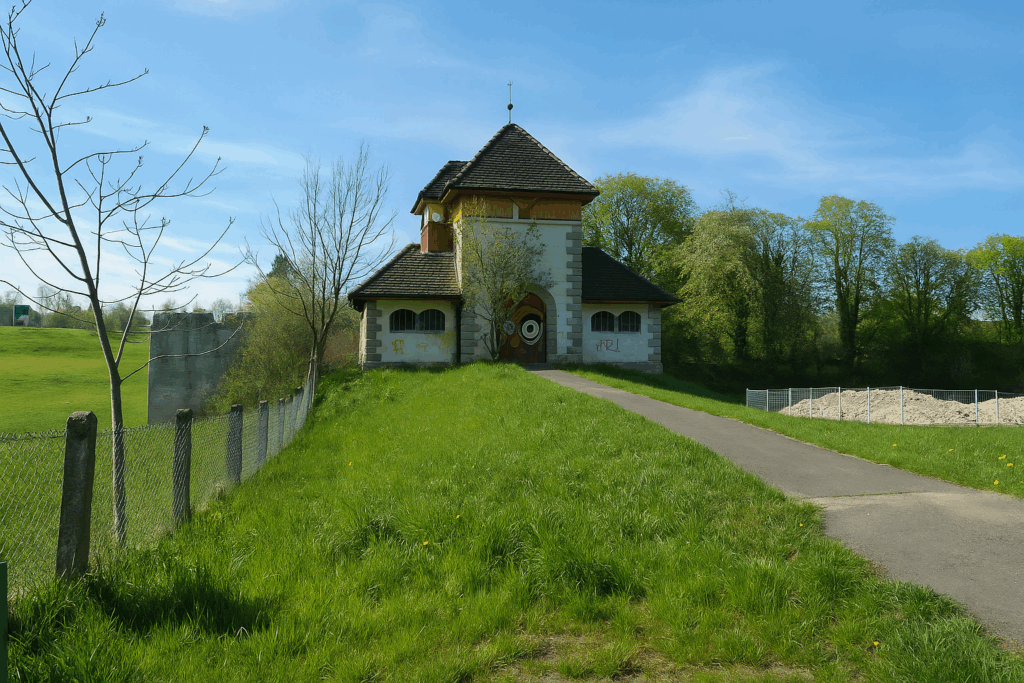

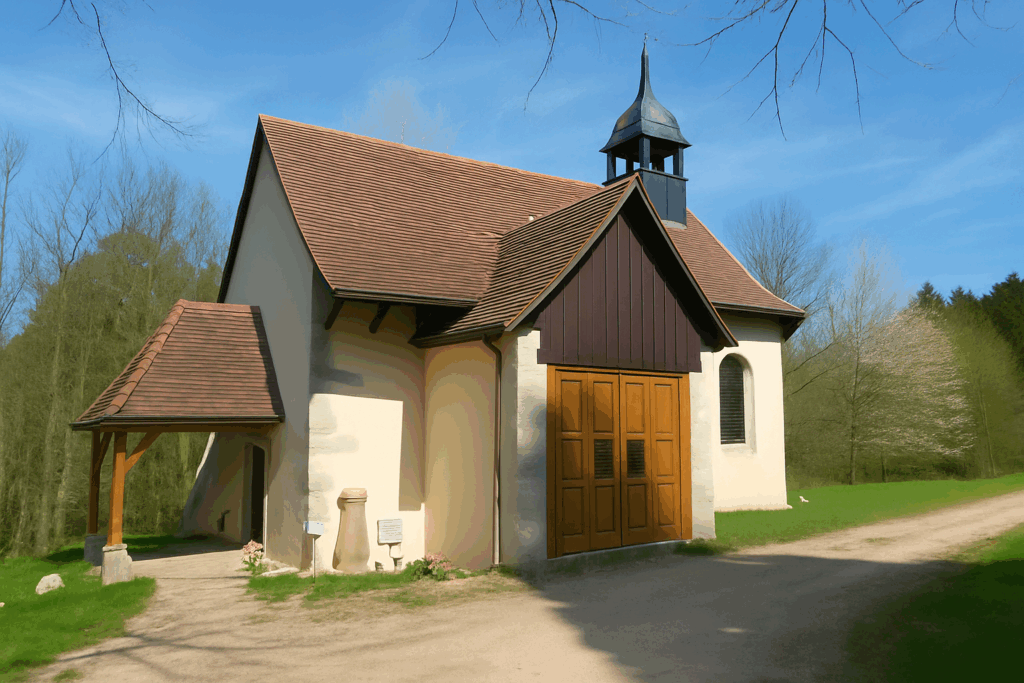

A little higher up, the path becomes calmer and more measured. It softens and moves forward in an almost perfect forest silence, until it reaches a beautiful clearing. This is where the St Brice chapel is nestled, in a peaceful and shaded setting. Just a short distance from the Swiss border, the place breathes serenity. At the fountain, fresh water still flows, inviting a well-deserved pause. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The St Brice site is truly charming. First mentioned in 1361, the chapel stands on an ancient location. Archaeological excavations have revealed a Neolithic site here, proof that people have passed through this place since the dawn of time. In the past, St Brice was a renowned place of pilgrimage, with an adjoining hermitage. More recently, an Alsatian style inn had taken over, attracting Sunday visitors. It is now closed and undergoing reconstruction, like the chapel itself, which had already been partially rebuilt at the end of the seventeenth century. |

|

|

|

|

From here, a wide forest path descends gently toward Oltingue. All markings are in agreement, with diamonds, shells, and Via Jura 41 signs. The walker can move forward without asking questions. |

|

|

|

|

The path then becomes a wide packed earth track, occasionally scattered with stones. It winds beneath broadleaf trees in a bucolic atmosphere. |

|

|

|

|

At the edge of the forest, pay attention. You emerge into a clearing that could be misleading. Here, the markings change. Yellow diamonds head toward Rodersdorf, while it is now the red diamonds that must be followed to reach Ferrette. A Compostela shell is indeed present, but it does not indicate the correct direction. Let us recall that on the true path, the top of the shell should point toward the way ahead. Here, it serves only as a symbolic reminder of the pilgrimage route. Keep this in mind. From this point on, it is the red diamond that must be followed. With the passing kilometres, you learn. One might even say that one has become an expert in this unusual marking system. |

|

|

|

|

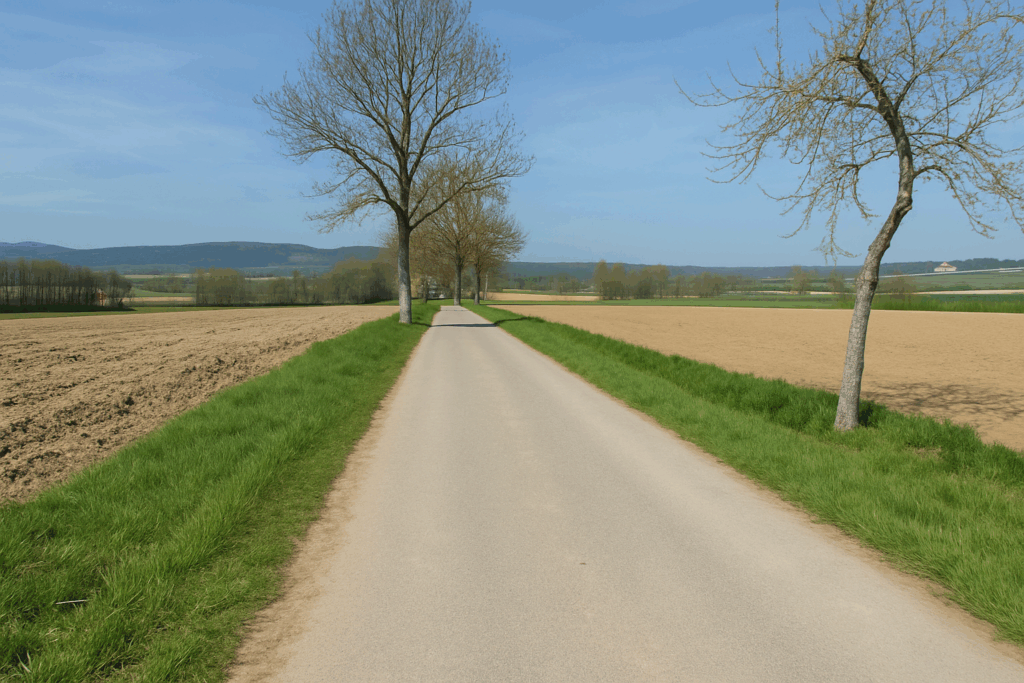

A steady descent then begins along a small asphalted road that winds between fields toward Oltingue. It is a calm walk, almost meditative, paced by the walker’s breathing and the sound of footsteps. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The closer you get to the plain, the gentler the slope becomes. From time to time, a red diamond appears on an old walnut tree, confirming that you are still heading in the right direction. Around you, cultivated fields stretch as far as the eye can see. |

|

|

|

|

Soon, the road reaches the plain. It runs alongside a small stream, the Limendenbach, which local riders gladly follow, in the shade of a peaceful patch of woodland. |

|

|

|

|

A little further on, the road crosses the Pfaffenbach, another small and equally discreet stream, then slopes up gently again toward Oltingue. |

|

|

|

|

TStill guided by the faithful red diamonds, you finally enter the outskirts of the village of Oltingue, along a quiet road lined with gardens and vegetable plots. |

|

|

|

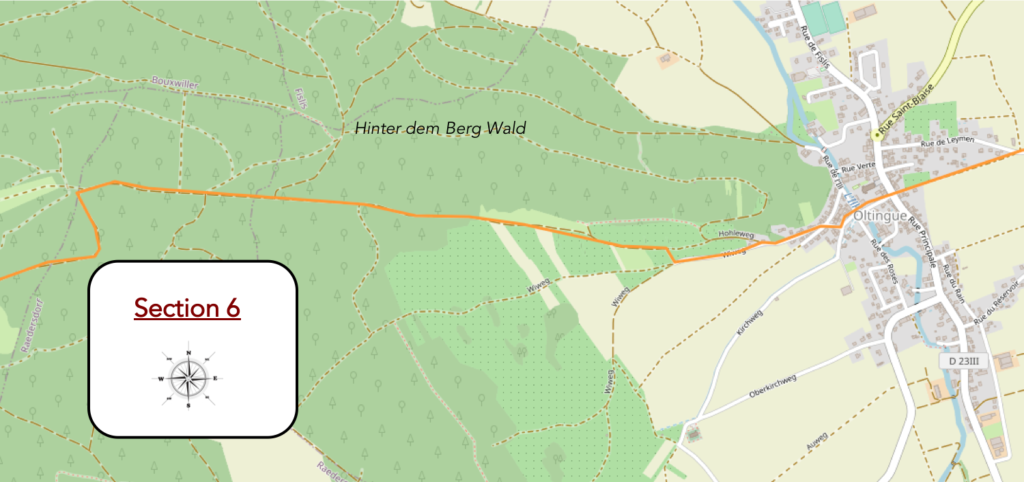

Section 6: Even more forest on the program

Overview of the route’s challenges: an ascent through the woods with pronounced slopes.

|

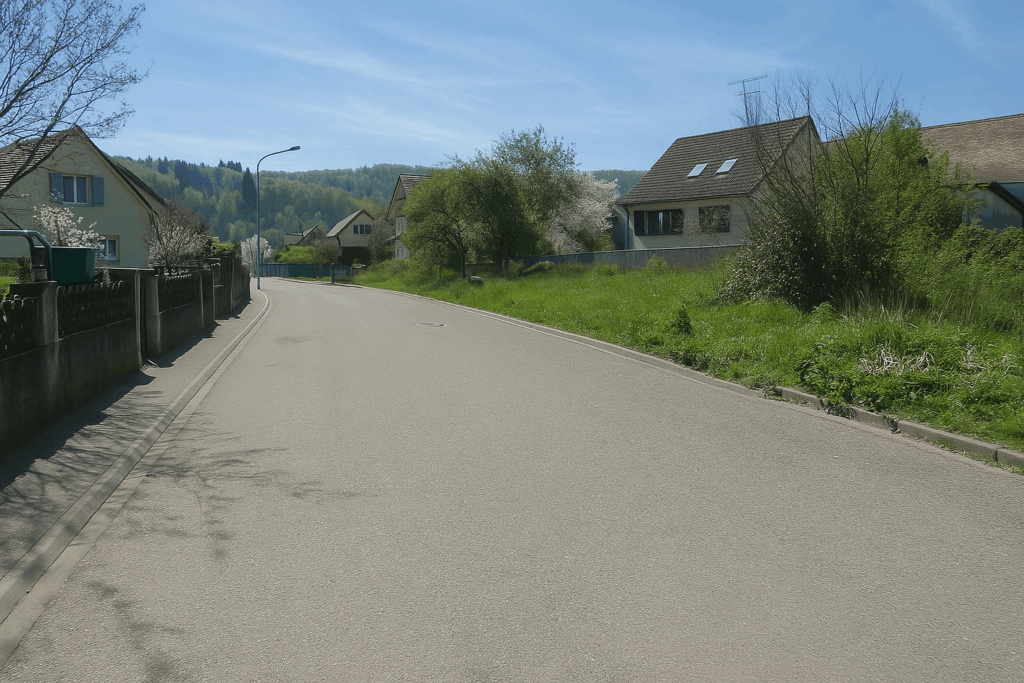

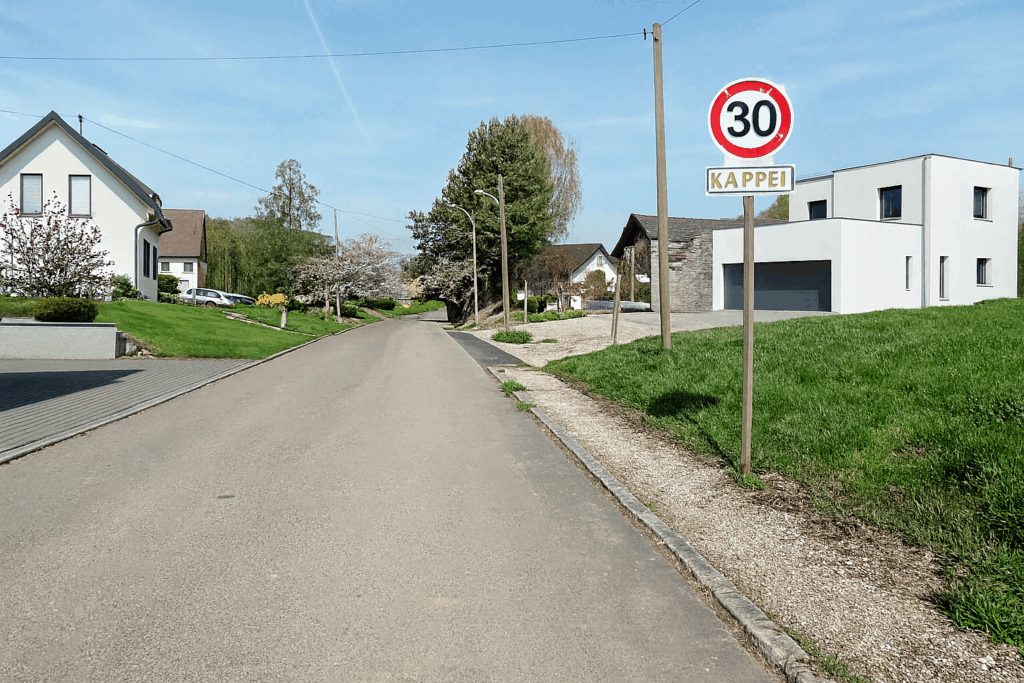

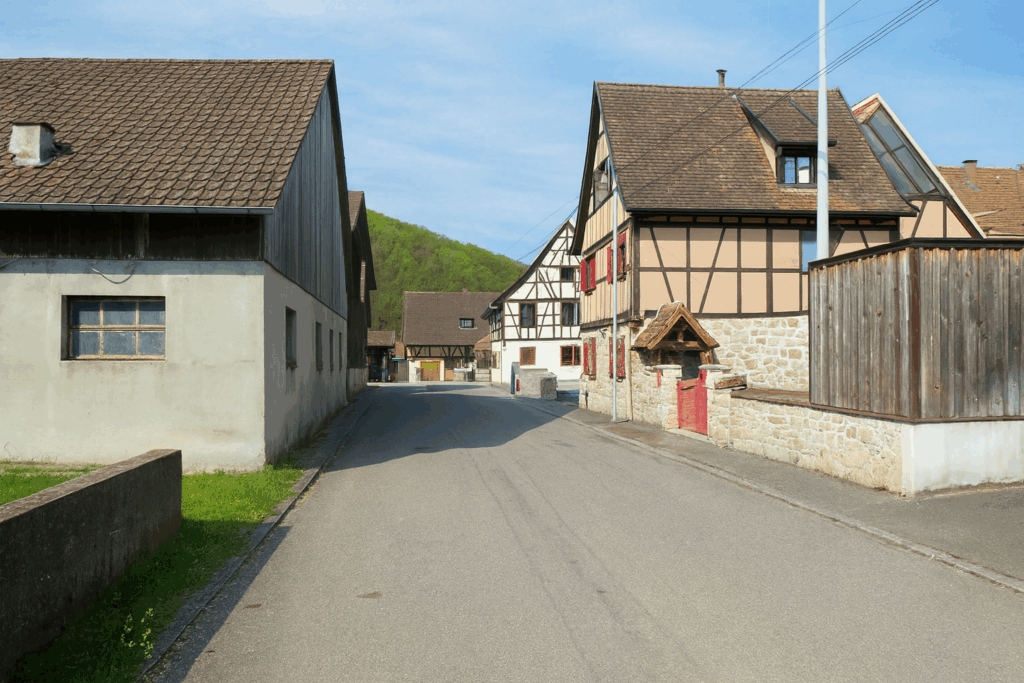

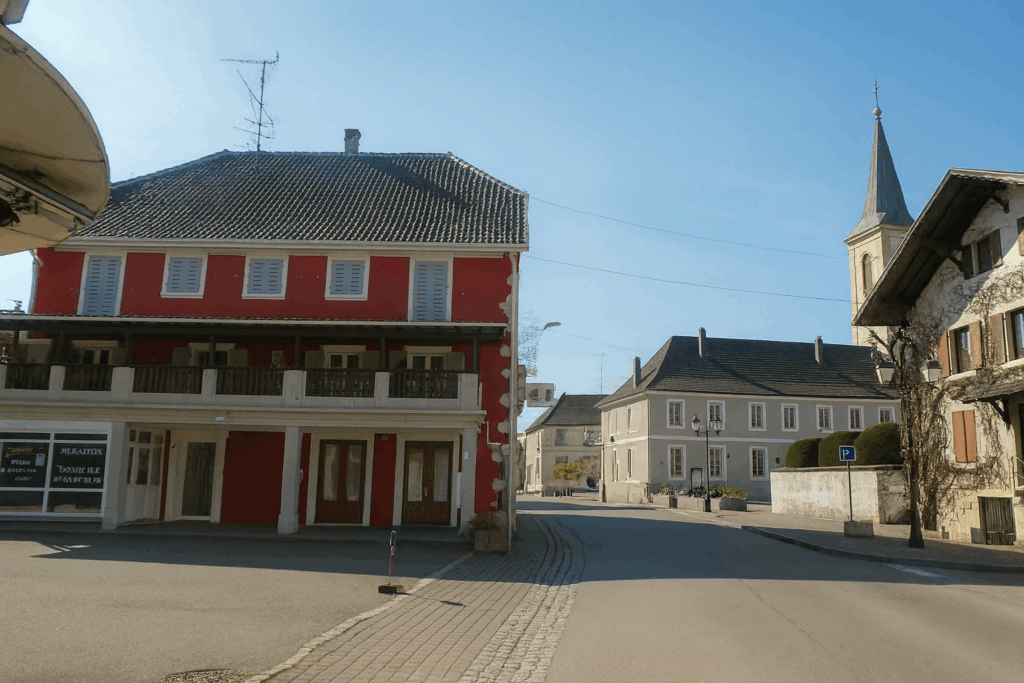

The road enters the village of Oltingue gently, where houses cluster along the main street. Here, many residents are cross-border workers who commute to Basel, while preserving the spirit of their village. |

|

|

|

|

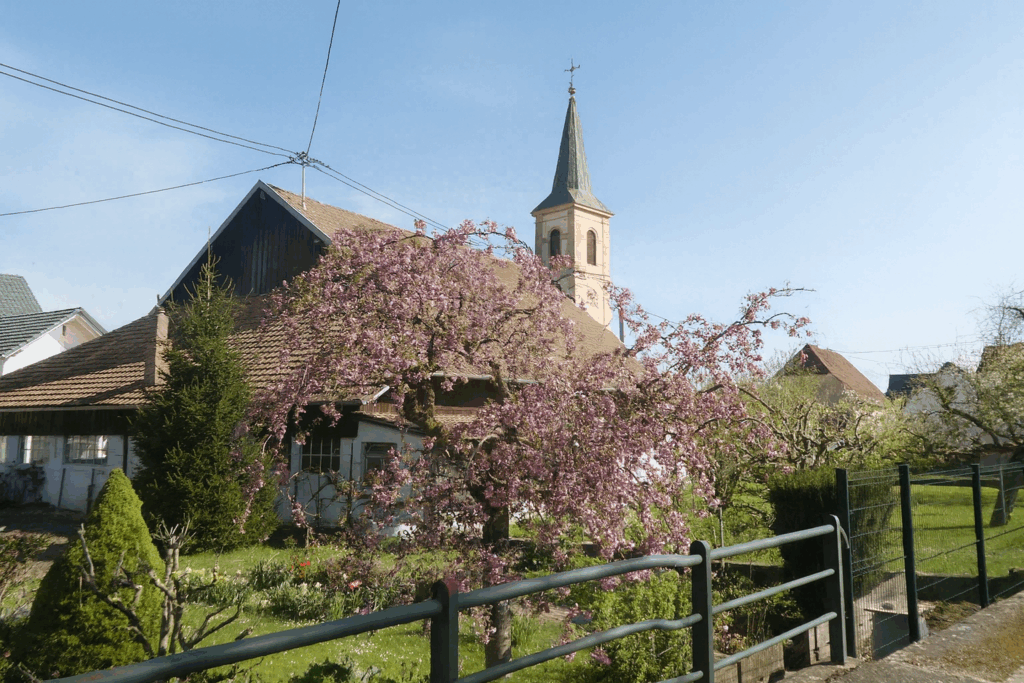

The road crosses this charming and very Alsatian village, with its carefully maintained half-timbered houses, often painted in pastel or bright tones typical of the region. It passes in front of the village church, with its modest steeple. Some pilgrims choose to make a detour to the St Martin-des-Champs chapel, located about one kilometre from the route. This often-overlooked place offers a welcome pause in a pastoral setting. For the others, as you leave the village, the path crosses the Ill River. The Ill is the great river of Alsace, which flows through the region from south to north before joining the Rhine. Here in Oltingue, however, it is still very young, barely emerging from its sources. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

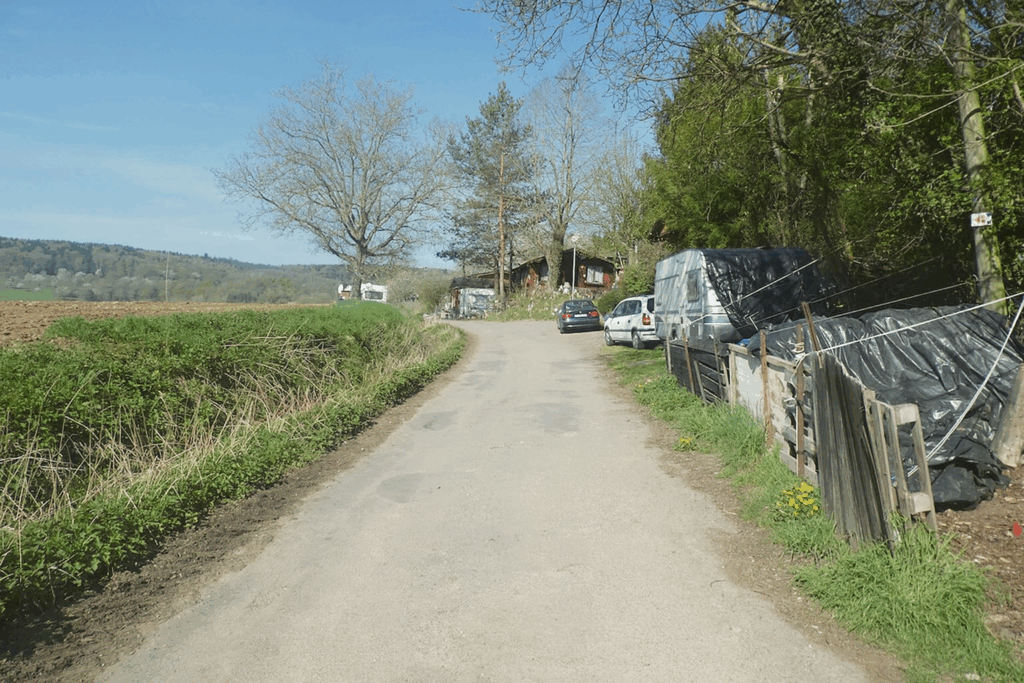

Still following the red diamonds, the road leaves the village and runs alongside a Roma camp set up by the roadside. Sometimes greetings are exchanged from afar, without many words, in mutual respect between passing travellers. |

|

|

|

|

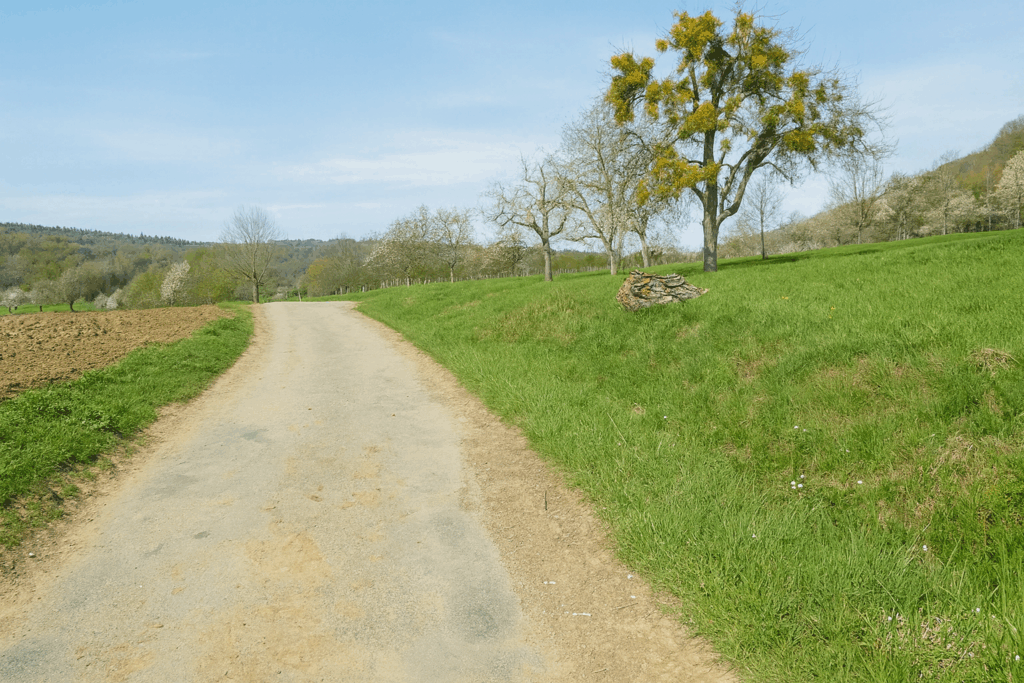

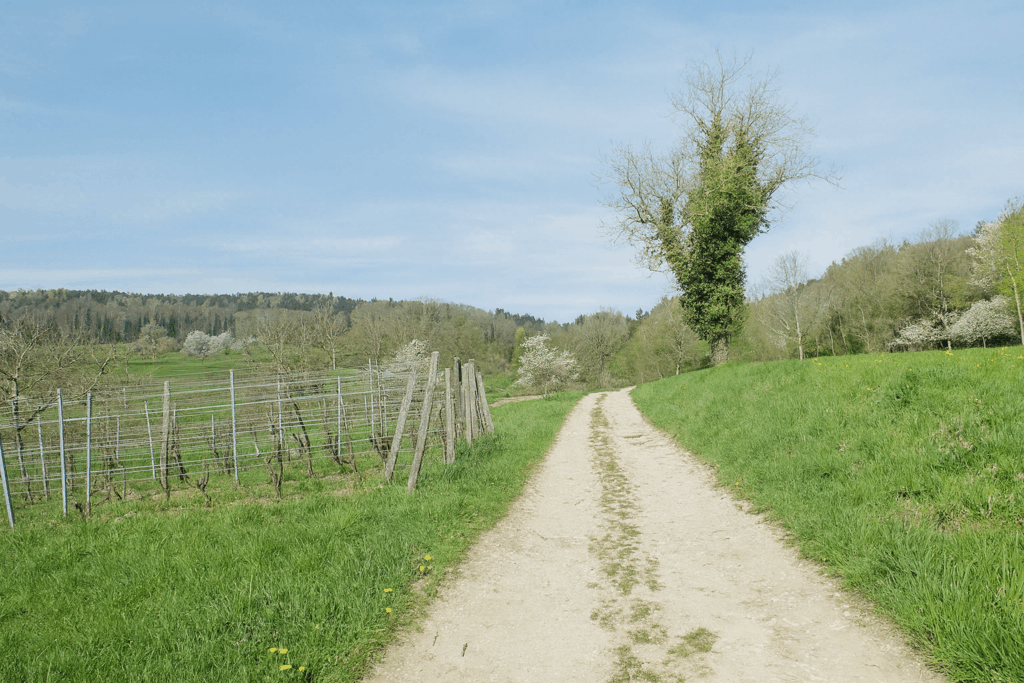

Then a wide dirt path, almost too smooth to seem real, gently enters an orchard. Apple trees, cherry trees, and sometimes even Mirabelle plums line the way. |

|

|

|

|

The road, still dirt but now stonier, soon enters the forest. |

|

|

|

|

This is the forest known as Hinter dem Berg. It immediately makes its presence felt through the verticality of its trees. Majestic silver firs, recognizable by their grey, fissured bark, dominate the landscape. There are also Douglas firs, often mistakenly called fir trees, yet standing tall and straight, almost arrogant. Oaks and beeches compete for light, while in the undergrowth, hornbeams, hazel trees, and young spruces struggle to find their place. The path itself keeps its bearings. The ever-faithful red diamonds reassure the walker. |

|

|

|

|

In this magnificent and airy forest, slopes remain gentle, never exceeding 10%. Long straight lines stretch over two kilometres, as if drawn with a ruler between the trunks. You must keep pace, walking straight ahead without letting the monotony lull the mind. Further on, stay alert. A trail marked with a yellow triangle invites you to turn off. This is the discovery trail, undoubtedly interesting, but it is not yours. The Way of St. James continues straight on, undisturbed. Here, it is long and seemingly endless, but the scenery is charming and the woodland remains open. |

|

|

|

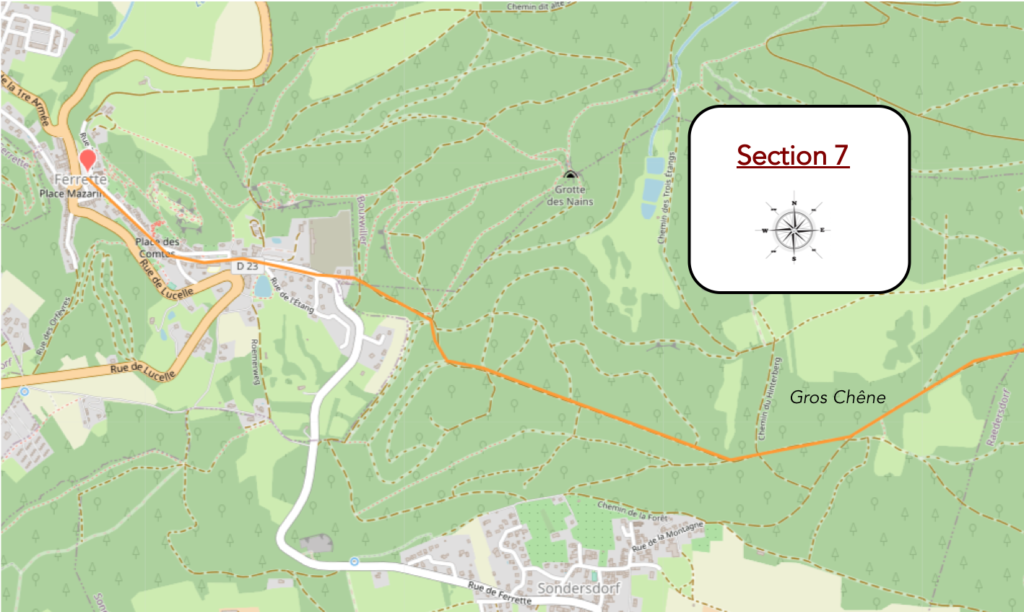

Section 7: Yet more rolling terrain in the forest

Overview of the route’s challenges: mainly a marked descent toward Ferrette.

|

And the path, never monotonous, continues forward beneath the tall trees. You might almost feel that the forest is gently pushing you from behind, as everything seems to invite you to keep going. |

|

|

|

Suddenly, on a giant beech tree, a direction sign appears. How curious? The red diamond turns into an orange diamond, while a yellow one points in another direction. Is this the effect of time, a gradual fading of colour? Or is it another itinerary crossing the way? Perhaps even a mistake. We may never know. Fortunately, the Compostela shell, even though it still points in the wrong direction, and the precise Swiss Via Jura 41 markings are there to recall the route to follow, toward the Gros Chêne of Sondersdorf and then Ferrette further on. That is enough to reassure the pilgrim.

|

The slope becomes slightly steeper. The path climbs calmly up to a junction, the one leading to the famous oak. Without hesitation, you turn aside, as the place deserves a few extra steps. |

|

|

|

|

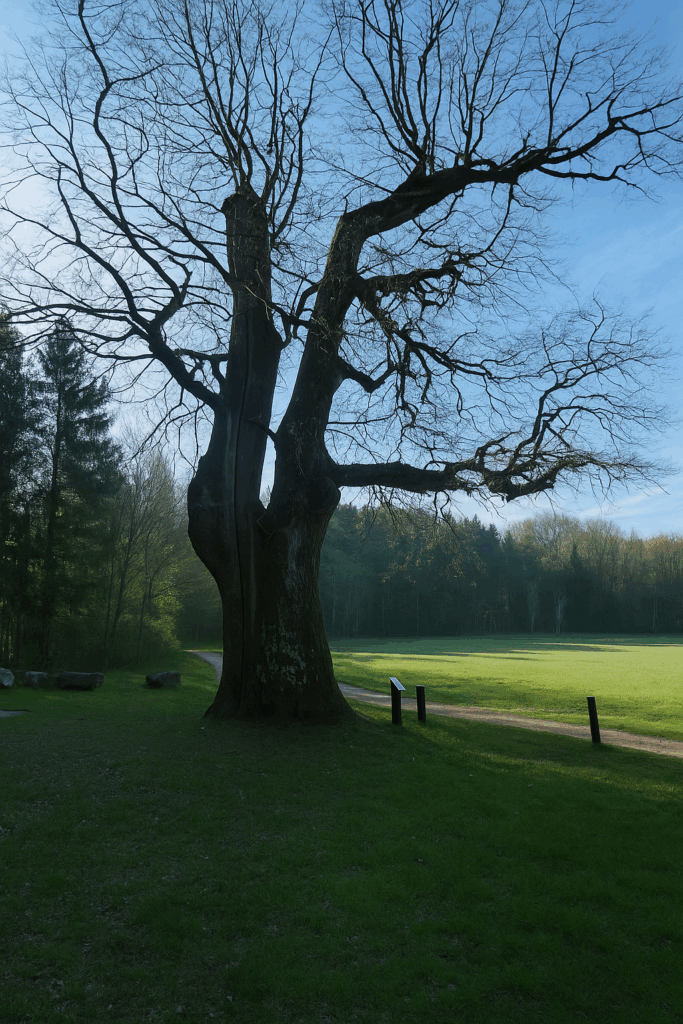

The Gros Chêne of Sondersdorf rests in a small clearing, outside both world and time. Some say it is 400 years old, others 500. It has witnessed centuries pass by, endured lightning, storms, and droughts. Once, it rose more than 25 meters high. Only about twelve meters remain today, yet what presence it still has. Knotted and twisted, it escaped the woodcutters. Not straight enough for beams, too massive for a mast. That may well have saved it. It has remained there, peacefully, surrounded by respect. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

From the old oak, a wide dirt path resumes beneath the beeches. You walk almost in silence, as if not to disturb the majesty of the place. But be careful here. The next junction is deceptive. Do not let shapes or colours mislead you. A blue triangle appears in the landscape, promising an escape toward Sommersdorf. But this is not the right way. Yours, the pilgrim’s path, continues straight ahead. And once again, the diamond has returned to red, faithful as ever. The Compostela shell also keeps its direction. And the Swiss Via Jura continues to accompany you. There is no doubt, this is the way to go. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The path, fairly stony, climbs gently through the deciduous forest. Tree shade accompanies the ascent. Higher up, another sign again indicates a direction toward Sommersdorf, and another toward ponds imagined to be peaceful, but far from the route. This forest is riddled with secondary tracks, exploration trails, and places to visit, each one an opportunity to get lost if you do not stay focused. |

|

|

|

|

Yet the atmosphere here is pleasant. At times, the forest opens onto long straight stretches, like natural corridors. At a crossroads, a cycle track appears, shared with other markings, including yellow diamonds once again. |

|

|

|

| And a little further on, red rectangles take over. Enough to lose all bearings if you do not keep your main line in mind. Fortunately, it is straight ahead, Ferrette is drawing near, and the slope slowly becomes gentler. | |

|

|

|

The path reaches the forest edge, opening into a calm clearing. Around you, beehives hum softly. One tells oneself that the forest is finally behind. |

|

|

|

But there is still one small detour proposed for the curious. A path leads to the Don Bosco cabin. That will be for another day. For now, Ferrette is straight ahead.

|

The wide path descends once more into the woods, crossing a small picnic area, like a final pause before the village. |

|

|

|

|

Below, the path becomes rougher. The path loses its regularity, and a trail runs alongside the first scattered houses announcing the village. You can feel the transition between nature and civilization. |

|

|

|

|

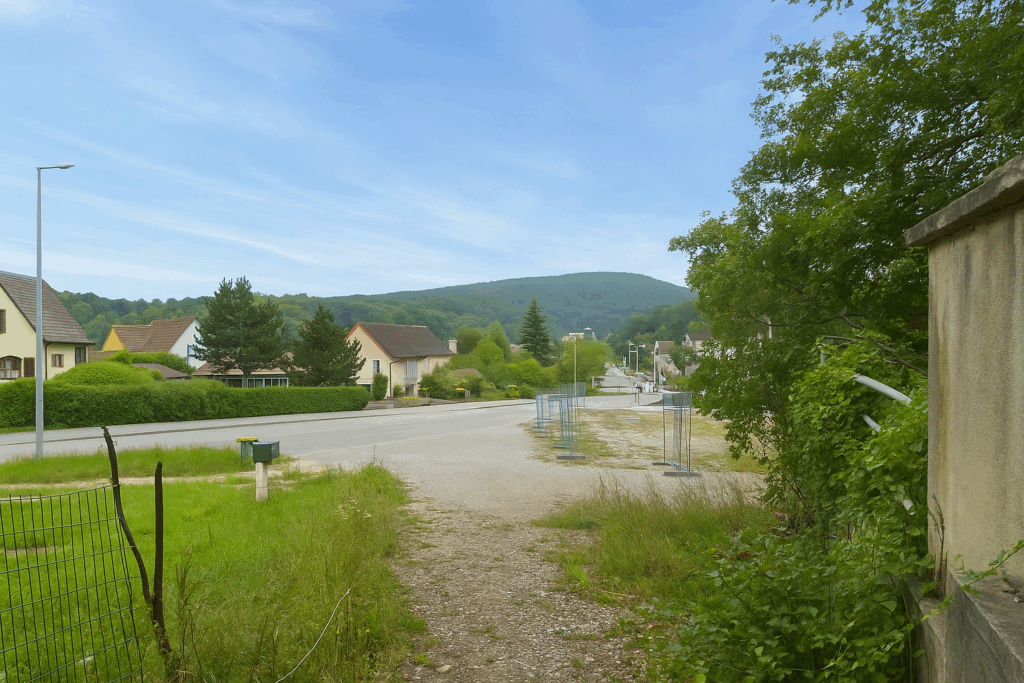

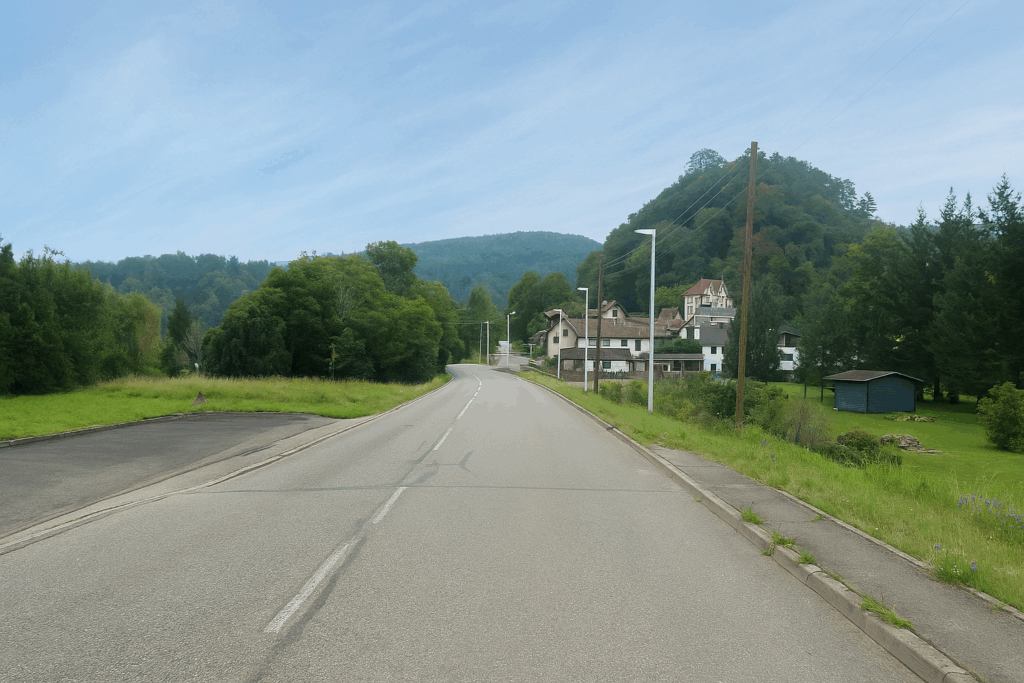

The narrow trail, steep and slightly slippery, drops quickly. And suddenly, there it is, the upper part of Ferrette. |

|

|

|

|

The route now follows the road, which gently leads you down toward the entrance of the village. |

|

|

|

|

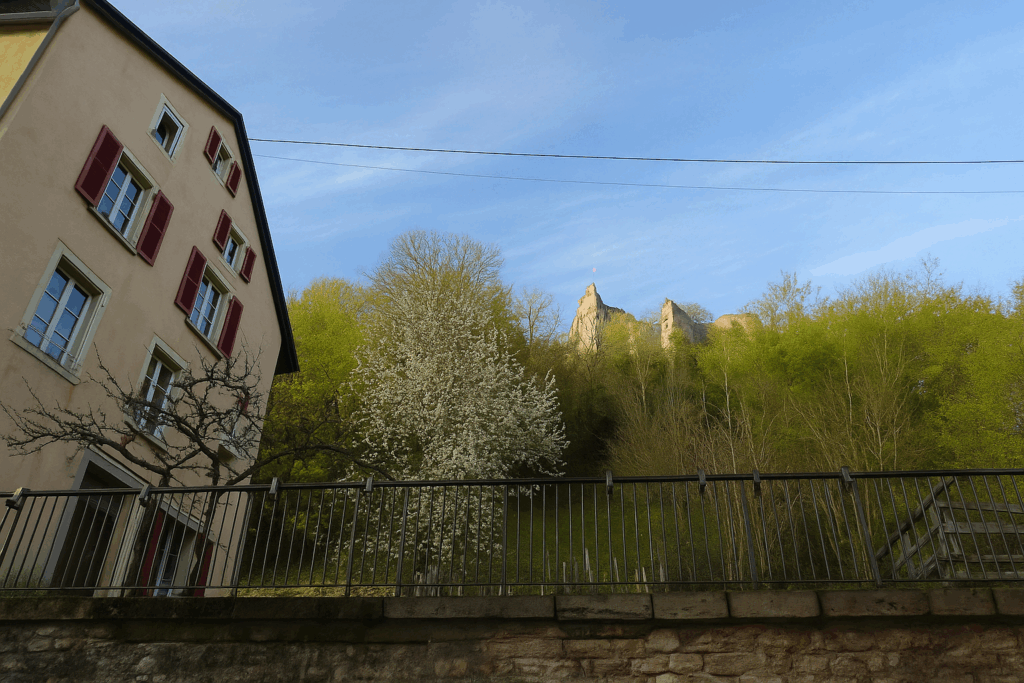

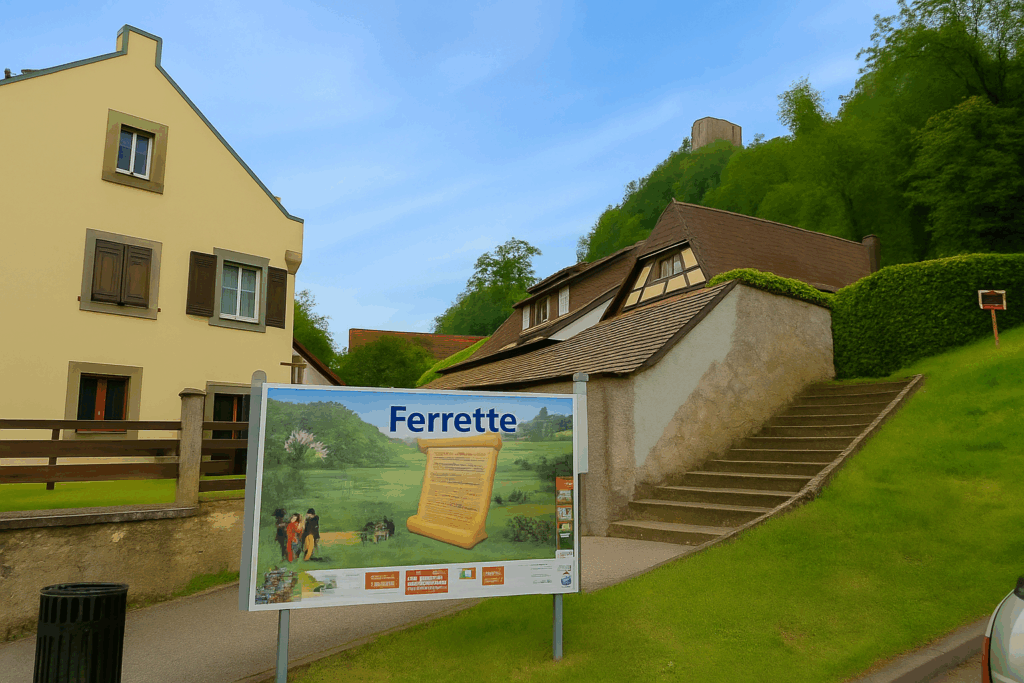

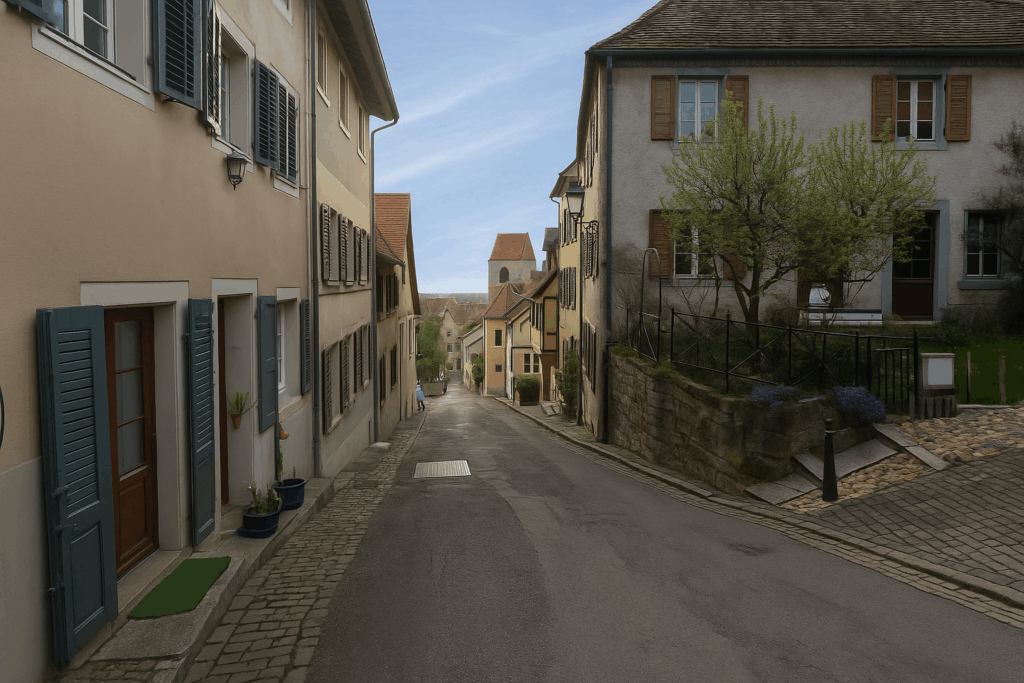

Ferrette appears, nestled on its slopes, dominated by the ruins of its castle. The village, with its closely packed houses, climbs up the hillside in a peaceful and ancient atmosphere. |

|

|

|

Ferrette, with its 700 inhabitants, has a long history. As early as the beginning of the twelfth century, a castle belonging to the Counts of Montbéliard is mentioned here. They founded the County of Ferrette, which would become one of the major lordships of Alsace in the Middle Ages. The region was contested, with Swiss, Austrians, and Burgundians succeeding one another, each leaving a trace. In the fifteenth century, the Austrians renovated the castle. It was at this time that the village of Ferrette developed at the foot of the fortress. Later, bankers turned lords added ramparts. Then the Thirty Years’ War broke out. The castle suffered successive assaults by Swedish and French troops. In 1648, at the end of the conflict, the lands were assigned to the King of France. The castle was not rebuilt. It became a ruin and would remain so. An unusual fact is that in the eighteenth century, through a sequence of marital alliances, the town came under the authority of the princes of Monaco. Even today, Prince Albert II officially holds the title of Count of Ferrette. Since 2011, the castle ruins have been the property of a private owner.

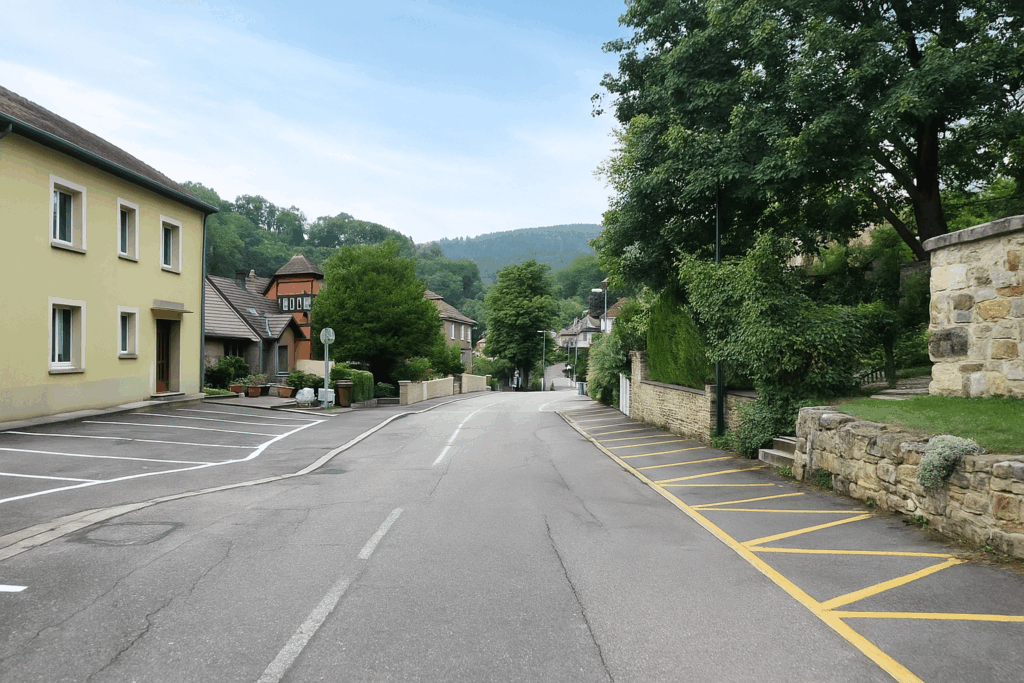

|

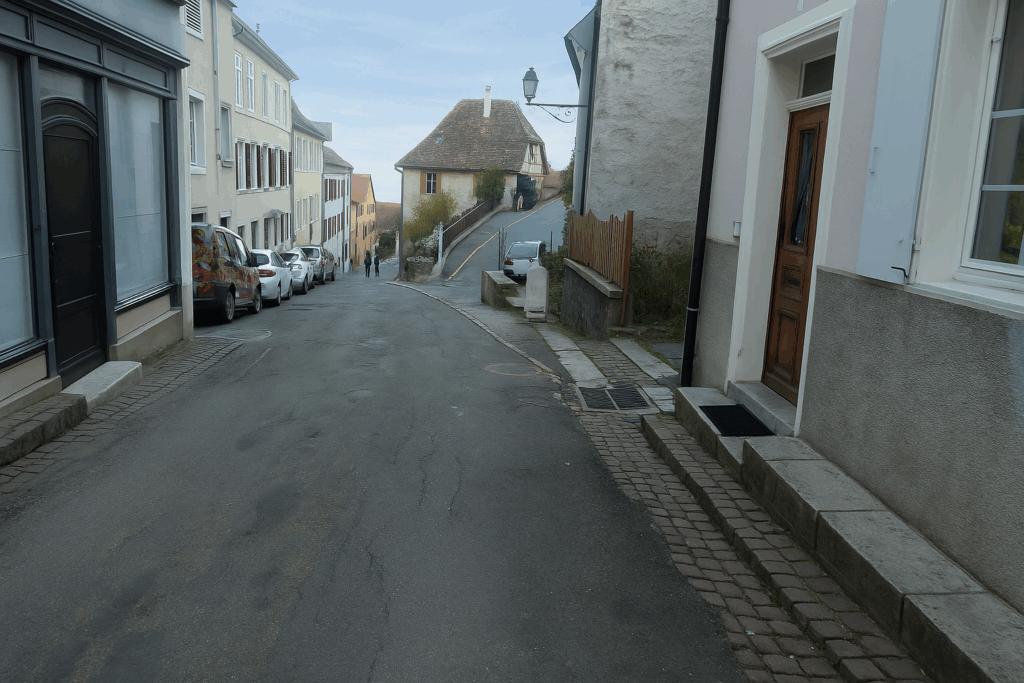

Ferrette is a magnificent village, but dauntingly steep. Perhaps the steepest on the entire Way of St. James. To reach the lower part of the village, where shops are concentrated, you must descend Rue du Château, sometimes facing slopes approaching 20%. |

|

|

|

|

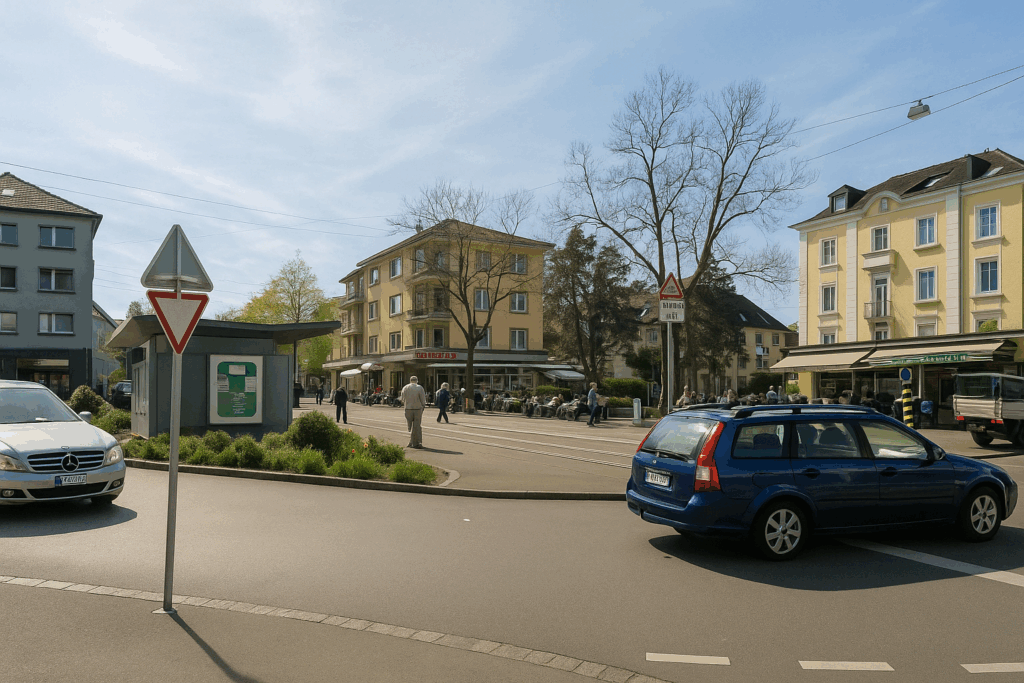

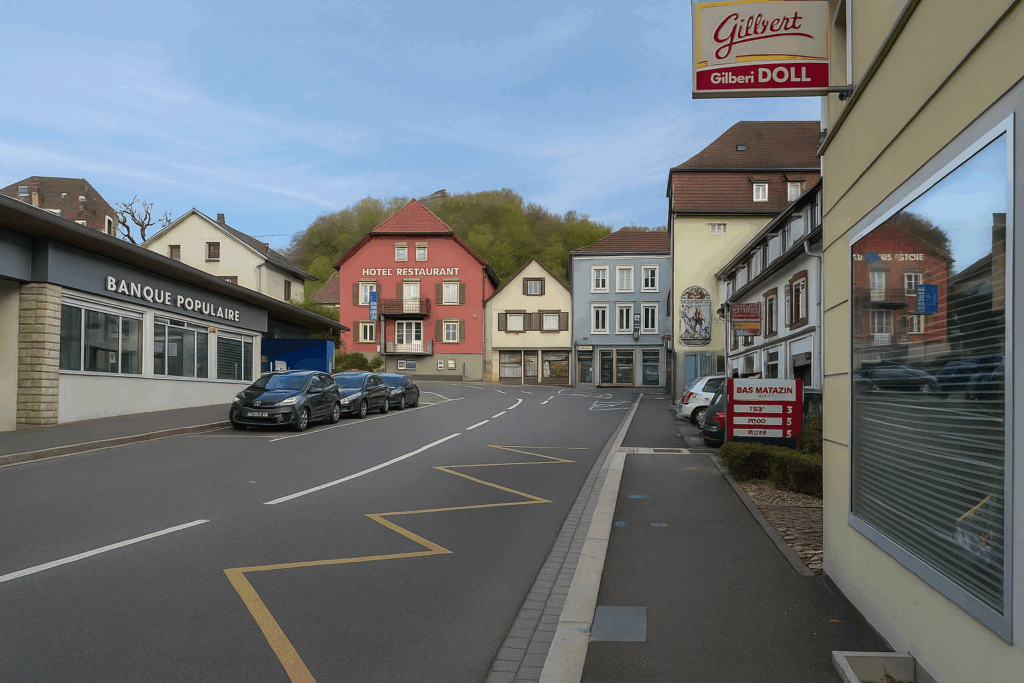

Along the way, you pass beautiful residences, some converted into guesthouses. The town hall, both austere and elegant, stands at the centre. Then you arrive at the commercial square, lively and welcoming. In the past, Ferrette was connected to Switzerland by a railway line. The train stopped at the border, as often happens in peripheral regions. |

|

|

|

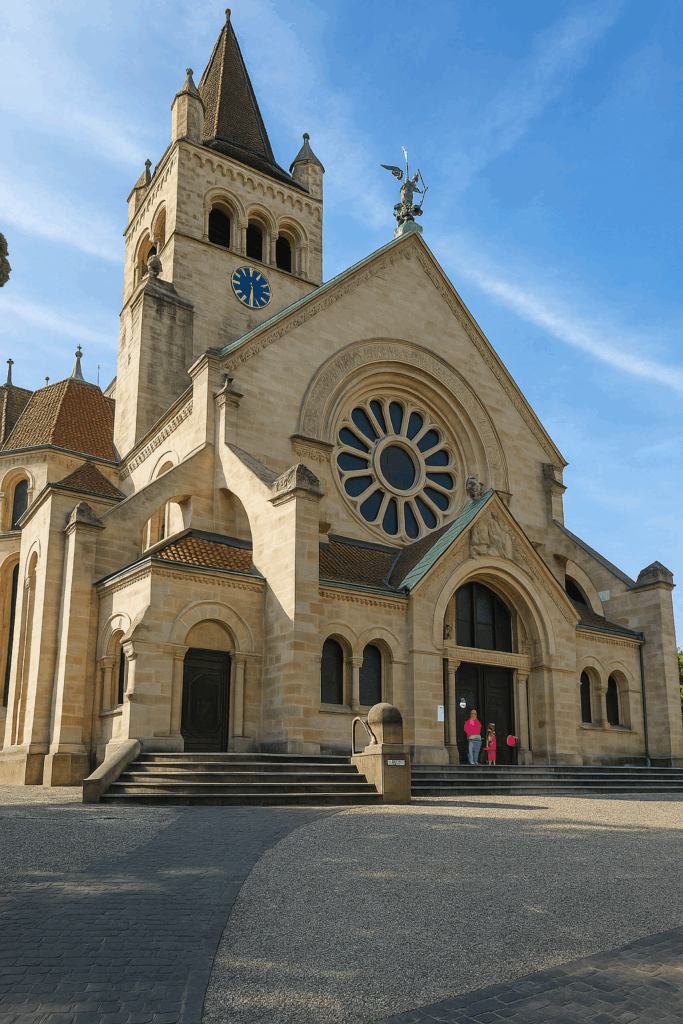

A little further on, the church of St Bernard-de-Menthon watches over the village. It dates back to the eleventh century, although it has been extensively modified and restored over time. Today, it is listed as a Historic Monument, a motionless witness to a millennium of history.

Official accommodations in Burgundy/Franche-Comté

- Restaurant Starck, 6 Rue d’Oberwill, Neuwiler; 03 89 68 51 58; Guestroom

- Hôtel Jenny, 84 Rue Hegenheim, Hagenthal-le-Bas; 04 89 68 50 09; Hotel

- Le Feiseneck, 42 Rue du Château, Ferette; 03 89 08 21 28; Guestroom

- Maison des 5 Temps, 5 Rue du St Bernard, Ferette; 03 89 40 38 31/06 31 90 93 20; Guestroom

- Hôtel Collin, 4 Rue du Château, Ferette; 03 89 40 40 72; Hotel

Jacquaire accommodations (see introduction)

- none

Airbnb

- Oltingue (2)

- Hagenthal (3)

- Vieux Ferette (2)

Each year, the route changes. Some accommodations disappear; others appear. It is therefore impossible to create a definitive list. This list includes only lodgings located on the route itself or within one kilometer of it. For more detailed information, the guide Chemins de Compostelle en Rhône-Alpes, published by the Association of the Friends of Compostela, remains the reference. It also contains useful addresses for bars, restaurants, and bakeries along the way. On this stage, there should not be major difficulties finding a place to stay. It must be said: the region is not touristy. It offers other kinds of richness, but not abundant infrastructure. Today, Airbnb has become a new tourism reference that we cannot ignore. It has become the most important source of accommodations in all regions, even in those with limited tourist infrastructure. As you know, the addresses are not directly available. It is always strongly recommended to book in advance. Finding a bed at the last minute is sometimes a stroke of luck; better not rely on that every day. When making reservations, ask about available meals or breakfast options..

Feel free to leave comments. That is often how one climbs the Google rankings, and how more pilgrims will gain access to the site.

|

Next stage : Stage 2: From Ferrette to Delle |

|

Back to menu |