From the Rhône to the foothills of the Pilat Mountains

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-auberives-sur-vareze-a-st-julien-molin-molette-par-le-gr65-73677546

| Not every pilgrim feels comfortable using GPS devices or navigating on a phone, especially since many sections still lack reliable internet. To make your journey easier, a book dedicated to the Via Gebennensis through Haute-Loire is available on Amazon. More than just a practical guide, it leads you step by step, kilometre after kilometre, giving you everything you need for smooth planning with no unpleasant surprises. Beyond its useful tips, it also conveys the route’s enchanting atmosphere, capturing the landscape’s beauty, the majesty of the trees and the spiritual essence of the trek. Only the pictures are missing; everything else is there to transport you.

We’ve also published a second book that, with slightly fewer details but all the essential information, outlines two possible routes from Geneva to Le Puy-en-Velay. You can choose either the Via Gebennensis, which crosses Haute-Loire, or the Gillonnay variant (Via Adresca), which branches off at La Côte-Saint-André to follow a route through Ardèche. The choice of the route is yours. |

|

|

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Today, you will continue your journey across the vast plain of the Bièvre-Valloire, which you have been traversing for many days, to finally reach the majestic Rhône at Chavanay. From this point, the landscape changes dramatically. You will leave the Isère department and enter the Loire department. Goodbye to the plain, hello to hills, small mountains, and puys guiding you towards Le Puy-en-Velay. In four to five days, you will reach Le Puy, the iconic starting point that many pilgrims, mostly Europeans and French, consider the true beginning of the Camino de Santiago. A simplistic vision, isn’t it, this so French idea that France is the center of the universe? Yet, the numbers speak for themselves: on average, 150 pilgrims depart from Le Puy daily, while sometimes 3,000 arrive at Santiago in Spain. So?

In the art of construction, the concern for proximity has always prevailed in the choice of stones. While this choice was limited in Isère, as you have observed, Pilat and Haute-Loire rest on granitic and volcanic foundations, and the closer you get to Le Puy-en-Velay, the higher the density of volcanic rocks. From scree to quarries, construction materials were directly sourced. Here, granites, gneisses, and schists outcrop, with even some volcanic rocks like grayish phonolites, light trachytes, which from afar resemble limestone, or black basalts. Lauzes, these flat slabs perfect for roofs, often come from easily cuttable volcanic phonolite. The architectural heritage of this region is exceptional, with old and new houses testifying to the abundance of local materials. New constructions, akin to parasites, are rare here. Granite ashlar stones give facades a refined elegance. In this region, old constructions are distinguished by the great regularity of granite blocks, often gray. Granite walls are usually bonded with lime plaster. When roofs are not made of slates, often of volcanic phonolite, red tiles are found.

.

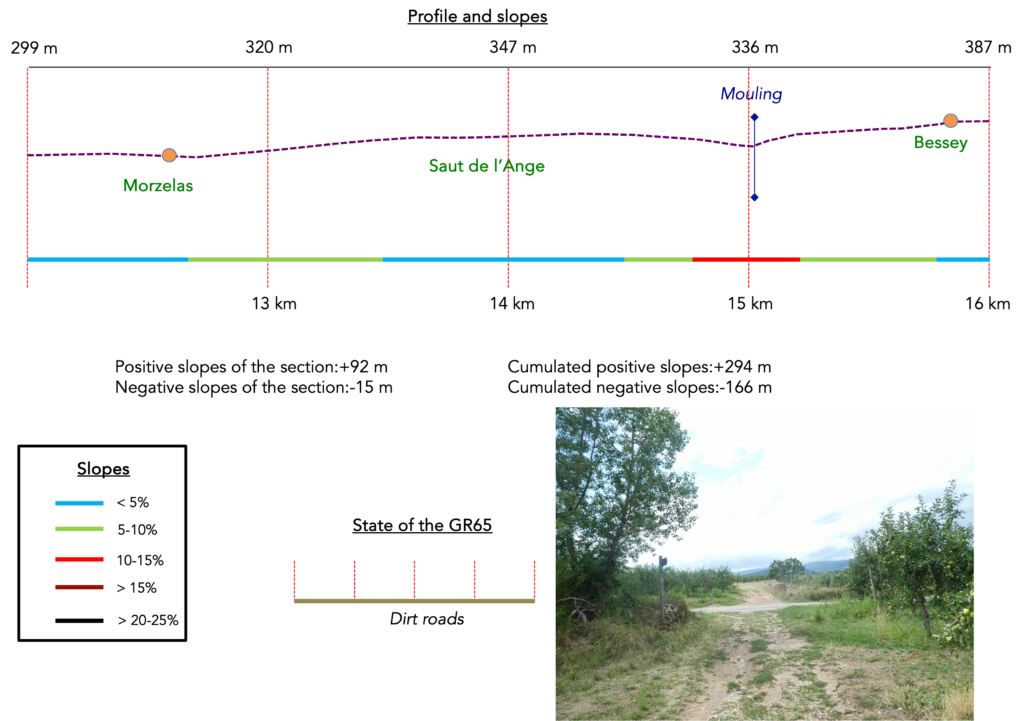

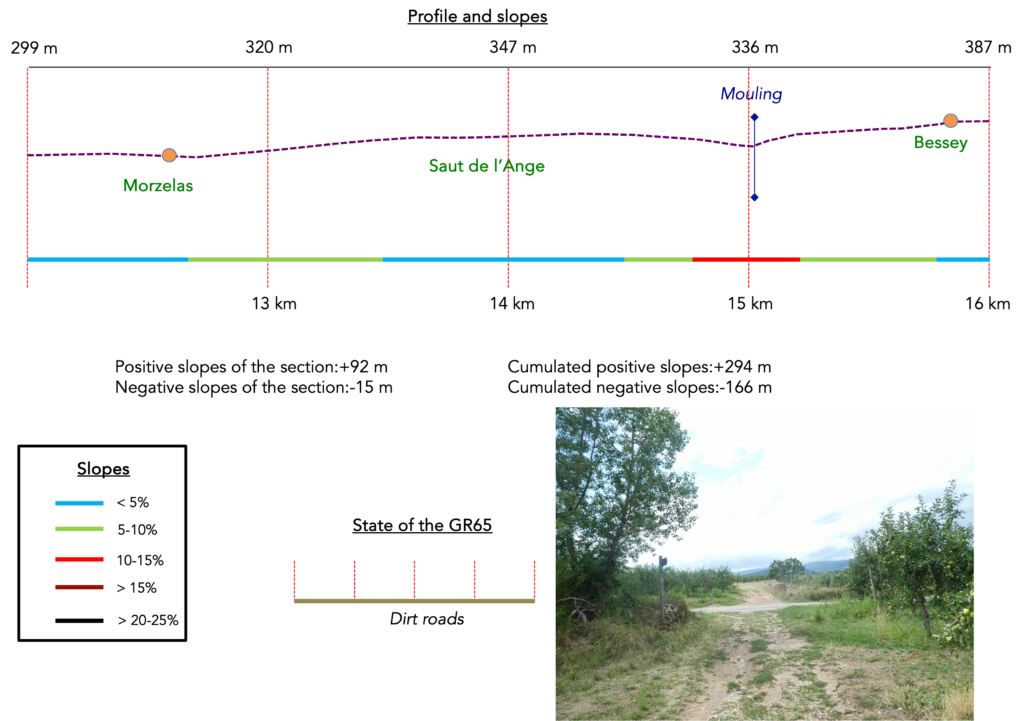

Difficulty level: The day reserves for you elevation gains (+710 meters / -361 meters) which, although modest on paper for a stage of nearly 28 kilometers, should not be underestimated. The first ten kilometers are flat, but then the 710 meters of ascent are concentrated over 15 kilometers, with a route that climbs almost continuously before descending towards Saint-Julien-Molin-Molette. Two segments are particularly steep, with slopes exceeding 15%: the climb of La Ribaudy, shortly after Chavanay, and especially the very demanding Ste Blandine Pass at the end of the stage. The descent to Saint-Julien-Molin-Molette also requires your full attention.

State of the GR65: Today, you will mainly walk on paths rather than tarmac, promising a better communion with nature:

- Paved roads: 12.7 km

- Dirt roads : 15.2 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

Section 1: Two small towns not far from the Rhône River

Overview of the route’s challenges: a course without difficulty.

|

Whether you spent the night in Auberives or simply transited by taking the Chemin des Vignes or following the RN7, you will eventually reach a roundabout at the exit of the locality, marked by the imposing presence of a press, a silent witness to the region’s winemaking tradition. This intersection is the essential starting point for embarking on the right route, a route that will reveal the discreet and authentic beauty of the surrounding landscapes.

|

|

|

|

At this point, you are at the end of the Route du Château d’Eau, at the intersection with the Chemin de la Pêche. The transition to the countryside begins here, where the first touches of greenery gradually replace the urban concrete.

|

|

|

| The road then gently moves away from the limits of Auberives, entering a fertile and generous territory. Orchards stretch as far as the eye can see; their natural richness nourished by soil conducive to various crops. The first trees appear, announcing the abundant orchards that characterize this region. |

|

|

| You will cross a vast expanse of orchards, where apricot, peach, cherry, and apple trees thrive under the sun. These orchards are adorned with protective nets, standing like sentinels to preserve the fruits from the assaults of birds and weather, especially hail, which can be devastating. |

|

|

| The road then permanently leaves the suburb of Auberives, delving further into the rural world where nature reigns supreme. The urban contours fade, replaced by an agricultural landscape. |

|

|

| Soon after, the GR65 leaves the pavement to become a wide dirt road winding through the orchards. The trees, perfectly aligned like a disciplined army, form a tunnel of greenery and life. This dirt road, humble but robust, becomes the guiding thread of a rural exploration, a plunge into the heart of an authentic and generous terroir. |

|

|

| Here, in the heart of this verdant labyrinth, the path briefly opens, plunging into the darkness of a wooded area before finding the bright light again. |

|

|

| After skirting the woods, the path rejoins the orchards before meeting a small road near Clonas-sur-Varèze. |

|

|

| Among the omnipresent orchards where beautiful fruits hang in season, the road quickly slopes up towards the heights of Clonas. |

|

|

| The GR65 moves away from the road again to venture through the meadows, offering a view of tranquil homes nestled behind their protective hedges, dominating the plain. |

|

|

| A small passage on the tarmac, and the GR65 gently descends from the hilltop, called the Chemin de la Côte, a path bordered by the benevolent protection of majestic maples, grafted chestnut trees with slender forms, and century-old oaks with dense foliage. Each step resonates under the natural arches of these imposing trees, their branches extending gracefully above you like the welcoming arms of a friendly giant, offering shade and coolness to the walkers. |

|

|

| Descending towards the small-town center, the silhouette of the church stands out against the sky, signaling the arrival at the bottom of Chemin de la Côte. This street, fully deserving of its name, opens like a passage between two worlds: on one side, the solemn calm of the countryside, and on the other, the discreet bustle of the locality. |

|

|

| Clonas-sur-Varèze, peacefully nestled in the hollow of the valley, reveals its discreet charms to those who take the time to linger. With its 1,500 souls, this small town is distinguished by its pebble houses from the Bièvre, silent witnesses of a bygone era. Soon, these traditional constructions will fade into the landscape, giving way to another type of building made of cut stone. |

|

|

Here, at the Villa Lucinius Museum, the Roman mosaics tell centuries-old stories. If you find it interesting and you are there on the right days and hours of operation, make a visit. It is also here that some pilgrims, who have not found refuge further along the route, spend the night.

| The GR65 then leaves Clonas by descending the Route de la Varèze. It’s quite a paradox. The last two localities crossed, Auberives and Clonas, bear the name of the river, but you will not see the river. It passes a little higher, to the north, to flow into the Rhône River. |

|

|

Section 2: Unremarkable return to the Rhône River

Overview of the route’s challenges: a course without difficulty.

| From Geneva, the Via Gebennensis has long meandered through gentle nature, only crossing modest villages and small towns. But here, the landscape abruptly changes. For a long time, the route will traverse a semi-industrial and semi-urban area before finally finding fresh air once the Rhône is crossed. Of course, it’s not like crossing the suburbs of Lyon or Paris, but it leaves an indelible mark on the landscape and on the pilgrim. These are 4 kilometers of total boredom!

Upon leaving Clonas-sur-Varèze, the road briefly ventures through the countryside before joining the D4, a departmental road animated by the incessant flow of vehicles. At a crossroads, where commercial and industrial activities line up, the GR65 continues its way. |

|

|

| On the other side of the crossroads, the route takes the road of the Station for a few hundred meters. Ironically, no train stops here. Finding a train schedule to cross this region is nearly impossible. It’s not the TGV connecting Lyon to Valence that passes here, only the TER connecting Lyon to Marseille. In these small towns, only the bus or car are viable means of crossing. What an irony for France! |

|

|

| The GR65 bends to detours to avoid the ghost station. As mentioned, you won’t find a station here. Instead, it’s a rocky mule path that rushes through the meadows, finally joining, after a short hill, another departmental road, the D37b, less frequented than the previous one. |

|

|

| The GR65 then follows the roadside of this road, passing under the TER Lyon-Marseille line before reaching the entrance of StPierre. This crossing to the Rhône is akin to a true obstacle course, which will undoubtedly leave a significant impression on the solitary hiker, unaccustomed to this struggle with urbanity. |

|

|

| Here, the GR65 leaves the main road to take a small road through St Pierre, heading towards St Alban-du-Rhône, a locality dominated by the imposing presence of a nuclear power plant. The surroundings do not shine with picturesque interest: the route winds between monotonous roads, offering fleeting views of characterless houses, often hidden behind thuja hedges. |

|

|

| To try to fill this void, a stop near a park where an old press stands offers a moment of respite. The road then descends towards a bridge. |

|

|

| This bridge spans the D37b, ready to cross the Rhône towards Chavanay. Next to it, a probably abandoned railway line accompanies the bleak landscape. |

|

|

| After crossing this bridge, the road continues through the outskirts of St Alban, taking the Chemin du Ranch. |

|

|

| Soon, across the fields, the glistening silhouette of the nuclear power plant appears, dominating the horizon with its industrial architecture. |

|

|

| At the village exit, where boredom seems to reign supreme, rows of soulless villas line up, devoid of any commercial activity. A hairpin turn leads the GR65 down into the plain, towards the Vieux Pont Road. |

|

|

| The road then unfolds in the plain, surrounded by cornfields and crossed by a high-voltage line. Although lacking elegance, it nonetheless represents a reunion with nature for the pilgrim, who still cannot claim the extraordinary or the sublime. |

|

|

| Soon after, at the intersection, the Vieux Pont Road rejoins the D37b once again. |

|

|

| Here, a narrow trail winds along the road until finally reaching the banks of the Rhône. You are almost out of this boring passage, a nightmare for some. |

|

|

Section 3: Beyond the Rhône, the GR65 begins to climb

Overview of the route’s challenges: The course is easy until Chavanay, followed by a challenging climb towards La Ribaudy, with slopes reaching nearly 20% in some places.

The trail and the road converge towards the grand bridge that spans the Rhône River.

| Under this bridge, the Rhône flows majestically, winding at the foot of hills where vineyard terraces dominate the river. Here, on these steep slopes, thrive the syrah and viognier grapes of Côte Rôtie and Condrieu, some of the world’s finest wines, whether red or white. What a delight for wine enthusiasts! Unfortunately, the route does not pass through these beautiful vineyards. Since your last encounter with the river at Yenne, the Rhône has swelled considerably, having swallowed the Ain, the Saône, and a few other smaller streams. It still lacks the Isère, the Drôme, the Durance, the Cèze, and the Ardèche to quench its thirst further. |

|

|

Lower down, almost at the water’s edge, the nuclear power plant stands peacefully. Although tsunamis are rare in France, a major incident such as an earthquake could result in prolonged contamination of the area down to the Mediterranean.

| At the end of the bridge, the GR65 arrives at a crossroads adorned with a flowered roundabout, which it skirts to escape onto a small industrial road. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the GR65 sneaks under a small now-silent tunnel, once crossed by passenger trains that ceased to run in the 1970s. A poignant testimony to the evolution of the French railway landscape, where even on the right bank of the Rhône, a once lively region, the silence of the rails predominates. The absence of trains is felt as far as neighboring Ardèche, leaving travelers to manage by other means. A sad reality for a nation that was once at the forefront of the European railway network. Here, only freight trains run. |

|

|

| However, this detour route from the bridge is intended to keep you away from the N86, the famous wine road that winds from Vienne to Valence, running through renowned wine regions such as Tournon and Tain-l’Hermitage. Every kilometer of this road evokes the excellence of the grand crus, celebrated and tasted around the world for their richness and character. |

|

|

|

Under the winding N86 flows the Valencize, a small river that accompanies the GR65 on its journey, with the calm rhythm of its murmuring waters.

|

|

|

|

A little further on, a path crosses an enchanting park, where the shade of tall trees invites relaxation. The nearby stream, with its crystalline murmur, seems to tell a peaceful and timeless story, like a walk of happiness in the heart of preserved nature.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Upon leaving the park, you discover the Square of November 11 and the magnificent winding ramparts of Chavanay. This small town is marked by its defensive past, with ancient ramparts still encircling dense buildings and narrow streets. Most of the streets are cobbled and semi-pedestrian, some even following the trace of the old 14th-century ramparts, erected when Renaud de Forez transformed Chavanay into a stronghold. Nearby stands the Church of Ste Agatha, whose origins date back to the 10th century, restored in the 17th century. Witness to the region’s tumultuous history, it even served as a granary during the Revolution before regaining its religious vocation. Recently restored, it embodies the permanence and faith of the inhabitants of Chavanay.

|

|

|

| Chavanay, with its 3,000 inhabitants, retains its original Gallo-Roman charm, enriched in the Middle Ages by a seigniory. The town has preserved its circular layout, its ruined towers, and its winding alleys, all lined with cut stone houses. Many pilgrims stop here, attracted by the tranquility and the availability of shops and accommodations. Notably, near the church, the Rue du Pèlerin hosts a pilgrims’ gîte. |

|

|

| The GR65 leaves the locality by crossing the fortifications near the Maison de la Tour. This ancient building, adjacent to the Serve basin, testifies to a past where it once supplied a farm along the banks of the Valencize. Today, the basin has been arranged to host nautical jousts, offering a picturesque setting for visitors. The tower, whose origin remains mysterious, was once part of a strategic outpost protecting the ramparts of Chavanay. Here, the GR65 crosses the Valencize, a peaceful stream lost in the dense vegetation at the bottom of the valley. |

|

|

| A road then winds above the town, quickly offering a contrasting view between the more affluent houses of the Loire and those of Isère. Here, cut stones reappear, testifying to the local traditional architecture. |

|

|

| The GR65 follows this road until reaching the fork leading to the Calvaire Chapel. |

|

|

| A rocky trail, sometimes strewn with large angular stones, climbs through a deciduous undergrowth. The steep slope, often exceeding 20%, is shaded by a dense collection of chestnut trees, with the more discreet presence of ashes, oaks, and beeches. |

|

|

| Higher up, the slope eases, a relief for all but the hardened athletes. The trail oscillates between plowed earth strewn with imposing stones and the softness of moss, amid lush vegetation. |

|

|

| Finally, the trail almost levels off at the chapel. This building has a rich history: its construction began in 1724 on land belonging to the Confraternity of the White Penitents, founded in the late 15th century. After the dissolution of the confraternity in 1777, the chapel was abandoned and then restored at the end of the 19th century by a reformed confraternity. It once served as a pilgrimage site with biannual masses and marked the end of the Stations of the Cross on Maundy Thursday. After the disappearance of this confraternity in 1892, the chapel once again fell into oblivion until its renovation from 2000 to 2003, thanks to the efforts of the « Friends of the Chapelle du Calvaire » association and the support of public and private funds. |

|

|

| From the chapel, the plunging view over Chavanay and the Rhône is offered to the pilgrims’ gaze. For many of them, this moment marks a nostalgic farewell to the river that has accompanied them for nearly ten days from Geneva. |

|

|

| After leaving the chapel, the trail resumes its tough ascent through a rugged path between moorland and undergrowth. Oaks and chestnut trees thrive on these poor and stony grounds, finding their nourishment in the harshness of the soil. |

|

|

| Higher up, the first vineyards emerge along the bumpy trail, marking the beginning of a continuous climb through the vineyards. Although the stones become less frequent, the slope remains steep amid the rows of vines that gradually multiply. |

|

|

| Condrieu is not far, on another neighboring hill. This region is renowned for its white wine made from the famous viognier grape, as well as for its red wine based on syrah, close to the Saint-Joseph and Côte-Rôtie appellations. Here, it’s the same grape varieties, but not the same wines, and the same high prices. The soils here are mainly composed of limestone and schist, far from the granite and volcanic rocks of its more renowned neighbors. Could this explain the difference in wine reputation? Perhaps, but no one knows how to scientifically unlock the secrets of grand crus. |

|

|

| At the top of the ridge, a wide and stony dirt road joins a small road that winds up to the hamlet of La Ribaudy. |

|

|

Here, on this ridge, a last look imbued with softness and gratitude is offered to the Rhône and the magnificent vineyard that, like a silent guardian, watches over the majestic river.

| La Ribaudy overflows with charm with its superb stone houses featuring meticulous architecture and impeccable joints. Each building breathes the history of the vineyards, and one can guess through their doors the discreet entrance to the cellars, where the precious nectar is cherished and refined. |

|

|

| Even after leaving the Rhône, the vineyards persist here, extending their orderly rows around the hamlet. At the exit of La Ribaudy, a trail begins a gentle descent into a small dale carpeted with vines. This typical terrace limestone soil is dotted with large limestone stones, embedded in soft, loamy earth. On the other side of the valley, fruit gardens stretch out, offering another peaceful tableau. |

|

|

| The vines here are terraced, bordered by limestone, granite, and schist walls. The region’s soil is a gentle mix of these stones, resting on a base of gneiss, granite, and schist from the Pilat massif, later enriched by limestone alluvium carried by glaciers. The trail then descends steeply into an undergrowth. |

|

|

The descent through this undergrowth, where tall deciduous trees rise gracefully and voluptuously, is short but immersive. These majestic trees, which you have come to appreciate in the region, accompany you to the small stream of Mornieux. This modest and secret stream winds peacefully through the dense forested dale.

|

|

|

| From the stream, the fairly stony trail gently slopes up through the undergrowth and its wild nature, leading to a small plateau. |

|

|

Section 4: In the woods, vineyards, and orchards

Overview of the route’s challenges: The course has some occasionally steeper slopes.

| Upon exiting the dense forest, a wider path extends to the place known as La Grange du Merle. In this region, wooden signposts exhibit a unique charm, a rustic and picturesque echo of the past and a silent witness to bygone eras. You immediately feel transported to another time, another life, where modernity has taken leave to make way for rural tranquility and simplicity. |

|

|

| From this point, orchards, primarily composed of apple trees, begin to compete with the vineyards to dominate the landscape. Each tree, resembling a small obedient soldier, contributes to the harmony of the scene. |

|

|

| The ground, increasingly soft underfoot, offers a sensation of softness and tenderness, akin to a mossy carpet. Modest shelters, constructed from large stone blocks, stand here and there, like distinctive signatures of many vineyards worldwide. These rustic, sturdy, and imposing shelters tell stories of protection against the elements and provide shelter for tools. |

|

|

| Further along, the path, still wavering between insidious pebbles that sneak into the soles and sandy soil that softens the steps, finally reaches the plateau’s edge. Here, it crosses Morzelas, a village imbued with the spirit of winemakers and farmers. The stone houses, with their red-tiled roofs, seem almost to merge with the landscape, while the vineyards and cultivated fields testify to the harmony between man and nature. |

|

|

| Ascending, a trail adopts a gentle slope, winding through an apparently disordered heathland, a harmonious chaos where orchards and vineyards mingle in bucolic anarchy. Here, nature reigns supreme, each plant finding its place in a precarious but magnificent balance. This journey, through this living tableau, is an ode to the serenity and simple, authentic beauty of the countryside. The landscapes, although sometimes harsh and imperfect, carry the indefinable magic of rural life, where each element contributes to a harmonious and enchanting whole. |

|

|

| When the trail reaches the place known as Les Combes, you arrive at a small plateau offering a breathtaking view of the surrounding region. Here, it is essential to highlight the precision and attention given to the path’s signage, with every detail carefully marked to guide the traveler. Alas, this rigor will not persist throughout the course. |

|

|

| Soon, the trail crosses a small road, then continues on the dirt of the high plateau. The announcement of the Saut de l’Agneau (Lamb’s Jump) just steps away evokes anticipation and excitement, an evocative name promising a fascinating discovery. |

|

|

| A wide path continues further its course, winding between vineyards and the occasional fruit trees dotting the landscape. In front of you, the white and blue tarps of horticulturists and market gardeners unfold, testifying to the land’s mildness for cultivation. The light and fertile limestone loam reveals itself to be much more conducive to planting than the heavy and stubborn clay. |

|

|

Next to it, the path heads to the place known as Le Saut de l’Agneau, a place whose name leaves one puzzled. One wonders where the lamb might have jumped, perhaps a symbolic leap or a simple local legend. Bessey, a charming village with a winemaking soul, is a little over two kilometers from here, an invitation to prolong the walk and discover other hidden treasures of this region.

| The path flattens straight through the monotonous plain, bordered by large meadows and discreet cultivated fields. Here, there are no more vineyards or fruit trees to break the monotony. On the horizon, the Pilat mountains majestically draw themselves, while hidden behind this mountain lies the city of St Étienne. |

|

|

| The crossing of this plain, which seems infinite in its simplicity, extends over more than a kilometer. The almost deserted nature confers an atmosphere of serene solitude. The path then begins to gently slope down towards the Mouling stream, crossing an old massive stone shelter, a vestige of a bygone era. This structure, perhaps fading with time, seems to be the silent witness of many seasons. |

|

|

| Further on, the path gently descends into the undergrowth, offering a refreshing respite under the benevolent shade of tall deciduous trees. Crossing even a small stream with a horse requires caution and skill. The stream’s coolness and the dense foliage create a soothing natural refuge, a welcome pause in this journey. |

|

|

The path then briefly slopes up on the other side of the stream. Often in these woods, stones are omnipresent, left by farmers who have yet to tame this wild part of nature. Wild oaks and chestnut trees proliferate here, adding a touch of wilderness to this pastoral decor.

|

|

|

| A wide path winds further through meadows and orchards towards the village of Bessey. From time to time, small groves of trees, mainly ashes, punctuate the landscape. Fruit trees, hidden under their protective tarps, reappear, adding a note of color and life to this bucolic tableau. |

|

|

| Further on, the path alternates between soft earth and sharp pebbles, creating a striking contrast under the walkers’ feet. Decorative low walls sometimes border the path, testifying to human effort to tame and embellish this wild landscape. |

|

|

| Bessey, the largest village on the route, finally reveals itself. At the village’s heart stands a church surrounded by beautiful stone houses. Here, you find the only water point on the route, a precious oasis for weary travelers. The village center offers dining options, a rarity in this region where other villages lack such services. |

|

|

The radiant stones, of all colors, breathe and vibrate throughout the village. This subtle mix of granite, gneiss, sandstone, and marl gives the village a unique and picturesque charm, a harmonious marriage of textures and hues that tells the geological and human history of the region.

.

Section 5: In the woods and orchards

Overview of the route’s challenges: The course is without problems, except for a small hill near the hamlet of Le Buisson.

|

From Bessey, the path winds through the orchards, where scattered vines stretch under the light shade of ash tree groves. Throughout the region, the soil is hard, compact, often strewn with sharp little stones that make walking difficult, though not insurmountable. Hikers quickly learn to tame this capricious terrain, finding in each step an intimate connection with the earth itself.

|

|

|

| In this land, crops are rare, with only a few plots of corn daring to challenge the predominance of the orchards. There is no wheat to be found, but rather an abundance of apple trees, whose fruits promise sweet harvests. Peach and apricot trees are scarce, but their sporadic presence adds a note of diversity. The orchards, jealously protected by large canopies, seem to guard a precious secret, offering a scene of discreet yet authentic beauty. |

|

|

| From one orchard to another, from one meadow to another, the GR65 soon leads to a small road at the hamlet of Mas de Goëly. There, a sandstone cross, planted on a granite base, rises majestically, symbolizing faith and tradition. |

|

|

| While Mas de Goëly has modernized with recent subdivisions, the neighboring village of Goëly retains its old-world charm. Its stone houses, whose age is lost in the memory of the stones, whisper ancient stories to those who care to listen. A more modest cross also adorns the street, and since pilgrims are few on the Via Gebennensis, small votive stones rarely have the chance to accumulate on the pedestals of the crosses along the way. |

|

|

| In Goëly, an old washhouse still stands, a silent witness to a bygone era when the clear waters still murmured with daily activities. Today, the water has long since dried up, giving way to a stagnant pond, the realm of toads. Frogs, once so numerous, are becoming increasingly rare, their melancholic songs gradually fading into the memory of the place. |

|

|

| At the village exit, the GR65 returns to beaten dirt and orchards, like a gentle invitation to reconnect with nature after paved passages. |

|

|

| Shortly after, it crosses a small local road and begins to climb towards a campsite, following a road that slopes up gently. |

|

|

| Then the beaten earth returns, a faithful companion of the route. The ascent begins in the orchards, offering a palette of greens and fruits that perfume the air with delicate scents. At the level of the campsite, which appears almost wild and untamed, the slope becomes steeper in the deciduous undergrowth. This solitary and peaceful place seems little frequented outside the summer months, maintaining an atmosphere of unchanging serenity. |

|

|

| Upon exiting this discreet undergrowth, the slope softens, and the GR65 joins a small road leading to the hamlet named Le Buisson. |

|

|

| Here again, beautiful stone houses stand gracefully, testifying to ancestral craftsmanship. A modest but significant sandstone cross highlights the religiosity of the place. Throughout the region, the basic building material is limestone or light sandstone rubble, giving the houses a natural harmony with their environment. |

|

|

| From Le Buisson, the road descends gracefully through orchards and meadows, offering soothing views of the surrounding countryside. |

|

|

| It quickly leads to the place called Chez Paret, where it lazily winds along the walls, often in the shade of ash trees. These trees, true kings of the roadside here, have been spared by the ravaging fungus of ash dieback that decimates their counterparts in so many other regions of Europe. |

|

|

| The GR65 leaves Chez Paret by the road, then finds a trail overgrown with tall grasses. There, a majestic iron cross stands with faith and elegance, seeming to watch over travelers. |

|

|

| The route then resumes its course on a bad trail winding through sparse undergrowth and wild grasses before finding a wide path bordered by apple trees, inviting serenity. |

|

|

Section 6: From one little hamlet to another, between woods and countryside

Overview of the route’s challenges : The course is without problems, before the climb to Ste Blandine.

| The trail, often strewn with rough stones, winds through the deciduous undergrowth. Amid this abundance, ashes, oaks, and maples rise majestically, while chestnut trees, once more discreet, regain vigor. However, this revival is fleeting, as the higher you climb, the more these chestnut trees dissipate like ghosts at dawn. |

|

|

| After crossing the tiny Fayen stream, which gets lost in the wild grasses and lush vegetation, the trail emerges from the woods to stretch across a field of large pebbles. A fascinating geological curiosity is revealed here: it’s as if the moraines of the Bièvre had migrated to this place. Perhaps they have, but they have largely dispersed over time, creating a unique and captivating landscape. |

|

|

| Then, beyond the disorder of nature, a wider path traverses rolling meadows. Ahead, the large village of Saint-Apollinard and its church loom on the horizon. Below, a factory belonging to the Justin Bridou brand, established in 1981, stands. This charcuterie packaging plant, owned by the Aoste Group, the leader in French charcuterie, is part of the large multinational Campofrio Food Group, a Spanish-Mexican conglomerate. It’s surprising to note that the sovereigns of French charcuterie are no longer French. The meats come mainly from China and the United States. This multinational is present all over the globe. It is also curious to see this establishment perched here, on the heights, far from the highways of the plain. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the path continues its gentle descent, heading towards the discreet hamlet of Bazin. |

|

|

| Then, a nature trail returns to the undergrowth, skirting stone walls, winding among maples, oaks, ashes, and clusters of wild chestnuts. Here, nature seems to have been left to its own rhythm, preserved in its original splendor, evolving with minimal human intervention. |

|

|

|

In this verdant setting, wild nature bursts forth with all its vigor. This landscape, oscillating between mineral harshness and the softness of trees, presents a striking contrast, accentuated by the stone walls that the peasants may have erected for aesthetic reasons. Small oaks proliferate along the poor lands, covered with large stones. Further on, it seems that the path has been cleared of its most cumbersome stones. Here, these are no longer the rounded pebbles of the Isère, but sometimes angular limestones, adding an authentic touch to this wild decor.

|

|

|

|

The GR65 then deviates slightly, crossing an alley of walnut trees, to discover a washhouse that seems to languish peacefully at the entrance of the village of Pourzin.

|

|

|

| A paved road winds through an extraordinary place that would make all the other villages in the region envious, with its magnificent stone houses built to withstand the test of time. However, it is unfortunate to note that these villages seem to be primarily open-air museums, rarely frequented by their inhabitants, and apparently devoid of true centers of social life. Despite everything, it is evident that a few souls persist in these places, as evidenced by the few vehicles parked here and there. |

|

|

| The road then continues towards the village of Saint-Apollinard, whose church can be glimpsed behind the orchards, although the GR65 does not head there. |

|

|

| It then leads to the hamlet of Curtil, where the GR65 leaves the road to plunge once again into a path winding through a deciduous forest. |

|

|

| The passage under the canopy is fleeting, and you find the pavement again at the entrance of the village of Mérigneux, with its noble stone houses shining under the sun. |

|

|

| Leaving the village, a road gently descends through the countryside before sloping up back towards the mountain, with slopes sometimes exceeding 10%, but this is just a teaser to whet the appetite. |

|

|

| A little higher, the GR65 deviates from the road to take a shortcut climbing under walnut and ash trees. |

|

|

| Well-prepared pilgrims know that moments of respite are ending and they face a more arduous section. Here, for nearly a kilometer, the route will impose slopes sometimes exceeding 25%. Yet, at the beginning, it winds a bit with contained severity on the grass until it joins the small road. |

|

|

| The passage on the road is short, near the place called Les Rôtisses, where the road ends in a dead end. Here, the first conifers appear among the deciduous trees, signaling a change in vegetation. The transition is marked by pines and spruces that stand proudly, contrasting with the chestnuts, maples, and especially the oaks that almost always dominate the arid slopes. |

|

|

| A trail then climbs first on the grass in the forest. The slope, though already severe, remains reasonable enough, allowing hikers to progress with some ease. The surrounding nature is luxuriously lush. |

|

|

| Then, the slope seriously steepens. The passage becomes demanding, not only because of the slope but also because of the state of the path where large stones emerge. Your shoes often slip on the rolling stones. The deciduous trees still clearly dominate the landscape in the dark undergrowth, and the sturdy oaks offer welcome shade. The dense canopy barely filters the sun’s rays, creating a subtle play of light and shadow on the ground, adding to the mysterious beauty of the place. |

|

|

Section 7: Up to the Ste Blandine Cross and the Combe Noire, before descending into the valley

Overview of the route’s challenges: The greatest difficulty of the course is the climb to the Ste Blandine Cross, which sometimes presents slopes exceeding 20%; the descent to St Julien is not easy either.

| The trail climbs steeply, winding through a clearing where the pines stand more majestically, like immutable guardians of this natural sanctuary. Before you stretches a field of pebbles, a shimmering mosaic on a vertiginous slope. A solitary stele announces that Santiago is still 1,600 kilometers away. Far from being discouraging, this reminder of the distance to be traveled invites meditation, especially when every drop of sweat seems to tell a story of perseverance and dedication. |

|

|

| At the top of this tough climb, the slope hardly eases, but the stones become fewer as the path winds toward a modest cross, humbly planted on the embankment. This cross marks the entrance to the Ste Blandine gîte, a peaceful refuge for exhausted pilgrims. |

|

|

| Here, many walkers feel a true deliverance after the rigor of the climb, and many choose to surrender to the tranquility of this enchanting mountain place rather than continue towards St Julien-Molin-Molette. |

|

|

| The path then continues to meander through green meadows, flirting with the edges of the woods, up to the Ste Blandine Cross. Erected in 1895 and blessed during a mission, this protective cross, four meters high, watches over the plain below. It dominates the Rhône valley, like an architectural poem. |

|

|

Pilgrims, if they find the courage to climb the embankment to the cross, are rewarded with one last breathtaking view of the Rhône valley. The orchards, adorned with drapes, stretch out like living tapestries, enriching the journey with their bursts of color and fragrance. This natural belvedere, in clear weather, offers a spectacle where the Ardèche mountains, the Rhône, and the Alps blend into one magnificent canvas.

| From the cross the wide path meanders peacefully on the plateau, crossing green pastures where cattle sometimes graze. It descends slightly towards the forest, above which the rare roofs of the Combe Noire hamlet can be seen. |

|

|

| You are not walking at a very high altitude, around 700 meters, a height still favorable to deciduous trees at the expense of conifers. Gradually, the path resumes its ascent towards the top of the hill, with a very steep slope. The forest becomes denser, the darkness and coolness of the undergrowth adding a touch of mystery to the climb. |

|

|

| Soon, the path reaches the Combe Noire hamlet, perched at the top of the hill, with its sturdy stone houses testifying to the robustness and resilience of its few inhabitants, if any remain. |

|

|

| At this point, the GR65 route is unambiguous. Below, the village of Chatagnard is revealed through lush vegetation. The descent is demanding, often rocky, and the undergrowth offers a steep path with an incline of more than 15% over nearly a kilometer. Pilgrims who scrupulously respect the traditions and laws of the route, convinced they are following in the footsteps of their ancestors, will take this challenging trail. |

|

|

| There is certainly a much more relaxing alternative for souls seeking tranquility: the road. This road, although also descending, offers a gentle and moderate slope, sliding in the benevolent shade of deciduous trees. No pebbles to obstruct the way, just a pleasant, almost meditative walk under the green canopy. It is this road we have chosen, preferring the serenity of this peaceful descent. |

|

|

| Whichever choice you make, whether the ardor of the trail or the tranquility of the road, you will eventually reach the charming cross of the Chatagnard hamlet. This enchanting place, evoked by its very name, is a promise of chestnut trees lining the route, their branches intertwining as if to form a natural arch above your head. |

|

|

| The road continues to slope gently down under the hamlet, winding among dark spruces, carefully planted to remind you that this is not only the kingdom of wild chestnuts but a diverse landscape where each tree tells a different story. You will also pass by another modest cross, bearing witness to the spirituality that permeates this land. |

|

|

| But the organizers of this route, playful spirits, have preferred to reserve a surprise for you. Rather than letting you descend quietly to St Julien-Molin-Molette, they have traced a side path, mischievously nicknamed the Compostelle Path, to add a touch of authenticity. This path, far from being a simple route, makes you climb another hill, this time under the shade of majestic pines, adding an extra challenge to your journey. |

|

|

| Climbing higher, the path turns into a road that climbs further, crossing vast meadows where the grass dances in the wind. This ascent leads you to a housing estate of recent villas, modernity contrasting with the surrounding nature. From this point, you find yourself overlooking St Julien-Molin-Molette, with a stunning view of the village nestled below. |

|

|

| For the pleasure of your knees and joints, but also as a well-deserved reward after so much effort, the last stage of this journey concludes with a steep descent, more than 15%, on a road winding towards the heart of the village. It is a dizzying plunge, where each step brings you closer to the end of this adventure, leaving behind the beauty of the hills and the tranquility of the landscapes crossed. |

|

|

|

|

The small town has 1,250 inhabitants, built in a basin through which the Ternay river flows. The village has a long history. Its name evokes mills and grindstones, which are sharpening stones. The Gauls, then the Romans passed through here. The Romans exploited the lead mines here, rich in the region. Then time passed, and at the beginning of the 17th century, industries came to settle in St Julien, related to the exploitation of lead, silver, and copper mines, as well as the spinning of silks. At that time, the village was populated by many foreign workers. It is undoubtedly the silk industry that was the pride of the village. They used the water from the Ternay for spinning, twisting, and weaving scarves, and printing fabrics. All this has long since disappeared, the last factory having closed in the 1970s. But there are still traces of the old industry.

| On the church square, where beautiful modern fountains stand, the church rises. This 16th-century church was built in honor of St Julien of Brioude. The church is sober and bright. Its old 17th-century pulpit is classified as a historical monument. There is also a famous calvary here, which you will visit tomorrow. |

|

|

Official accommodations on the Via Gebennensis

- Accueil pèlerins, 16 Rue du 14 juillet, Clonas-sur-Varèze; 06 01 78 61 00/ 04 74 299 77 05; Gîte, breakfast

- Châtau de la Petite Gorge, 29/35 La Petite Gorge, Chavanay Stade; 04 74 87 29 80/06 26 03 49 72; Guestroom, breakfast

- Les Praries de Mary, RD1086, Chavanay Stade; 04 74 87 02 25/06 62 16 63 67; Guestroom, dinner, breakfast

- Gîte d’étape, 1 Rue de l’Ancienne Cure, Chavanay; 07 81 34 64 64; Gîte, cuisine

- Gîte Grégory, 15 Chemin des Vignes, Chavanay; 06 14 62 01 86; Gîte, dinner, breakfast

- Accueil randonneurs Gaillard, 3 Rue des Pèlerins, Chavanay; 06 85b 78 30 09; Gîte, dinner, breakfast

- Le Pigeonnier, 8 Chemin des Vignes, Chavanay;04 74 31 03 07/ 06 38 39 75 62; Guestroom, dinner, breakfast

- Gîte communal, Bessey; 04 74 87 36 83 06 84 30 67 53; Gîte, cuisine

- Bar restaurant Chez Carsi, Bessey; 04 74 87 36 41; Gîte, dinner, breakfast

- Camping La Maison du Tao, Le Buisson; 06 12 92 12 92; Gîte, dinner, breakfast

- La Buissonnière, Le Buisson; 04 74 87 41 37/06 72 13 16 88; Guestroom, dinner, breakfast

- Gîte de Ste Blandine, Croix Ste Blandine; 04 74 48 36 15/06 41 45 37 72;Gîte, dinner, breakfast

- Accueil randonneurs, Radio d’Ici, 6 Rue de la Modure, St Julien-Molin-Molette; 04 77 51 57 45/06 13 13 66 86; Gîte, dinner, breakfast

- Camping du Val Ternay, St Julien-Molin-Molette; 06 82 47 75 09; Gîte, dinner, breakfast

- Franck Pernet, Montée des Fabriques, St Julien-Molin-Molette; 04 77 51 54 93; Guestroom, dinner, breakfast

- Le Domaine des Soyeux. 599 Avenue de Colombier, St Julien-Molin-Molette; 04 77 51 56 04/06 74 30 35 06; Guestroom, dinner, breakfast

- Suryahome, 10 Rue du Mas, St Julien-Molin-Molette; 04 77 02 37 71/06 76 10 93 92; Guestroom, dinner, breakfast

Pilgrim hospitality/Accueils jacquaires (see introduction)

- Clonas-sur-Varèze (2)

- Chavanay Stade (1)

- La Ribaudy (1)

- Bessey (2)

- St Appollinard (2)

- St Julien-Molin-Molette (2)

If one takes inventory of the accommodations, lodging does not present problems on this stage. There are numerous possibilities all along the route, even outside of it. All shops are available in St Julien Molin-Molette, except for a bank. For more details, the guide of the Friends of Compostela keeps a record of all these addresses, as well as bars, restaurants, or bakeries along the route,

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 11: From St Julien Molin-Molette to Les Sétoux |

|

|

Back to menu |