In the woods of Chambaran before discovering another jewel of the Middle Ages

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

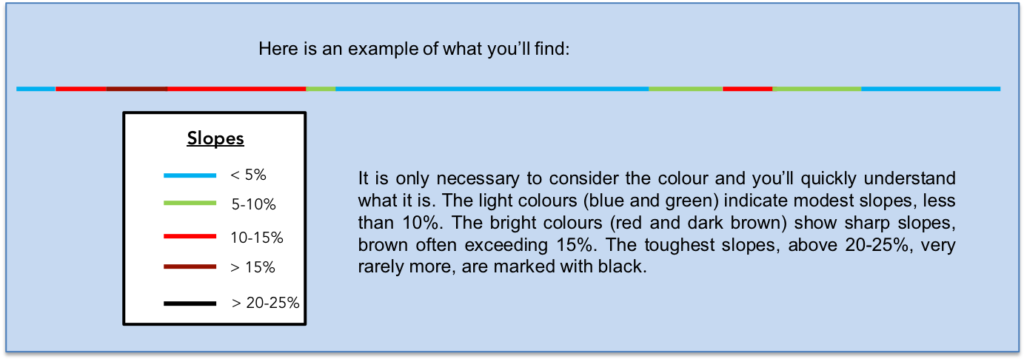

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the roads. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/marnans-auvergne-rhone-alpes-france-32806286

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in France without an Internet connection. Therefore, you’ll find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

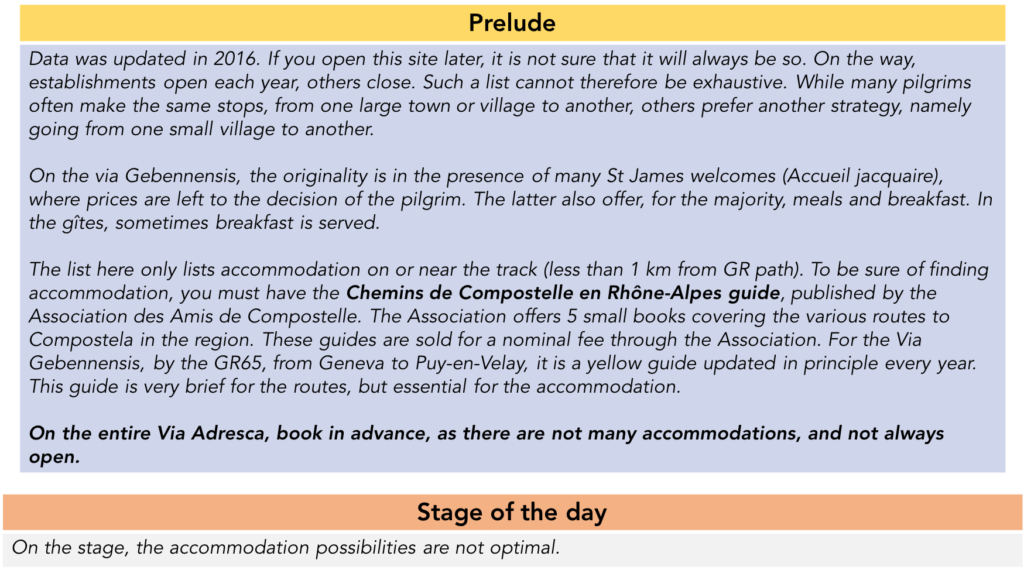

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Today’s stage is undeniably a great stage. Not only you’ll cross relaxing landscapes, magnificent forests, fields of pebbles scattered on the slopes, but it is also an initiatory journey through the religious currents of the Middle Ages. Dare we tell you that we had never heard of St Antoine-L’Abbaye? Neither do you, perhaps. Why doesn’t Isère advertise more for the marvels that hide in these places? So, here you are going to visit the Benedictines, the Antonines and even the Trappists. Quite a program, right?

| The Bas-Dauphiné is the alpine foreland, where molasse predominates, when it is in the form of compact rocks. But, on the way, you will hardly see any, because here it is the deposits of the Quaternary Era which occupy large areas and line most of the valleys. These were deposited on the periphery of the Rhône and Isère glacier tongues which descended from the Alpine massifs. The forests, long and numerous in the day stage, and often the poor soils, are most often made up of silt, sand and a little clay. Humus is often leached. Geography remains as simple as ever. Today, you’ll leave from the foothills of the Bièvre in Marnans, to reach the high plateaus and forests of Chambaran, and descend on the other side to the great valley of the Isère. (https://www.persee.fr/doc/geoca). . |

|

|

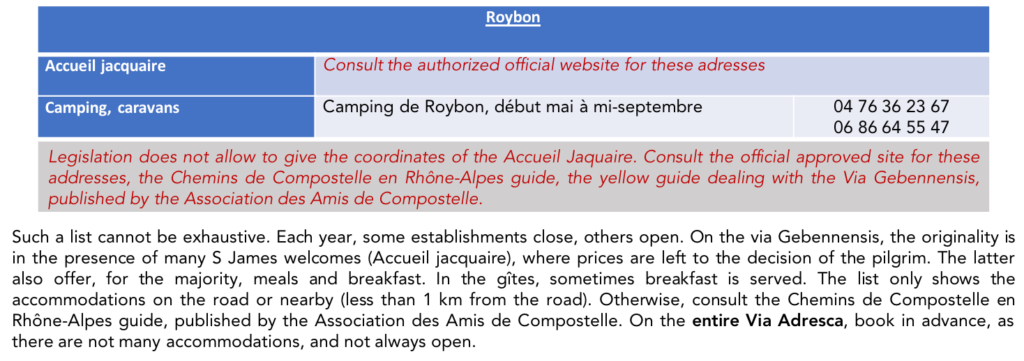

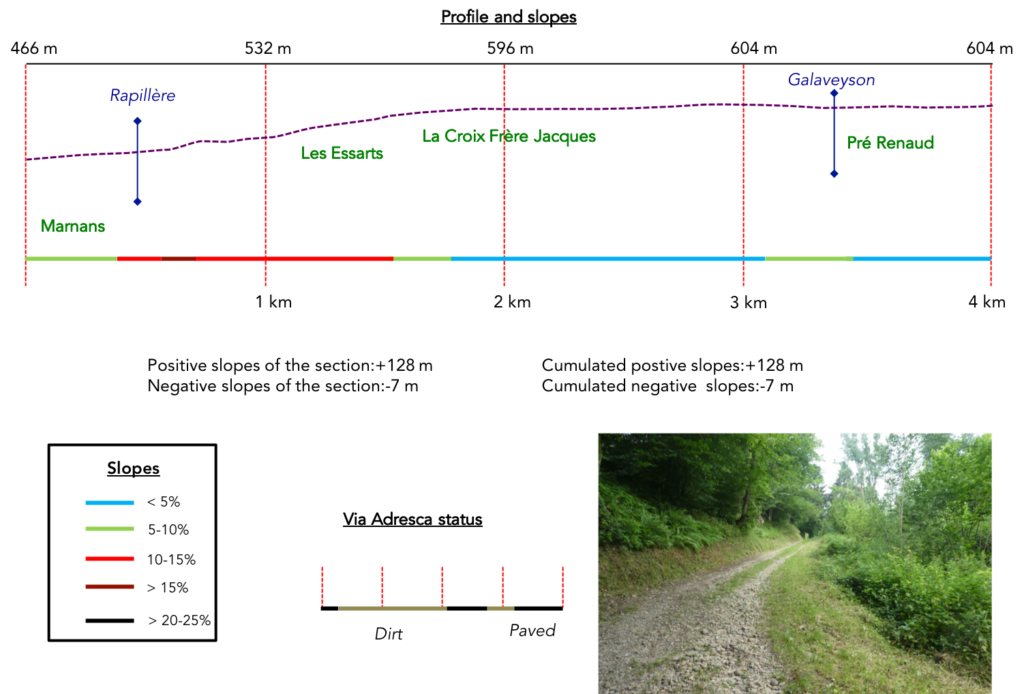

Difficulty of the course:

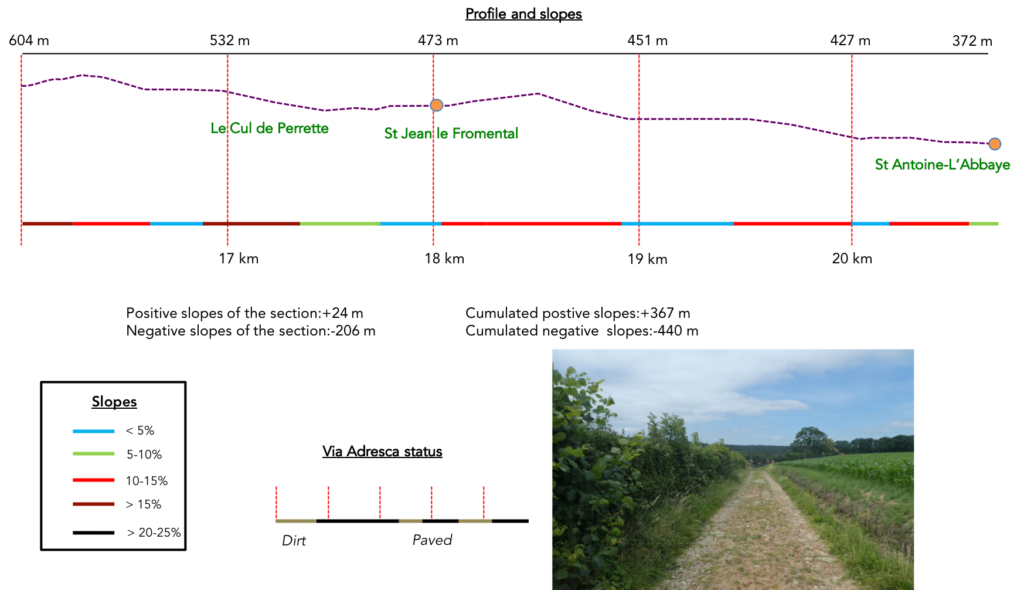

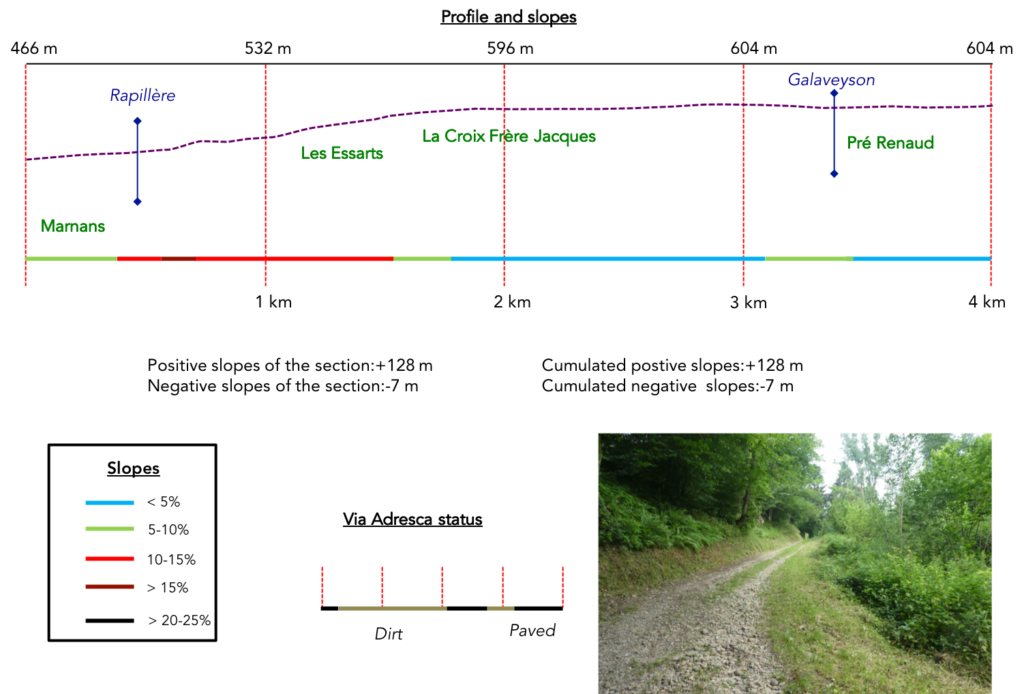

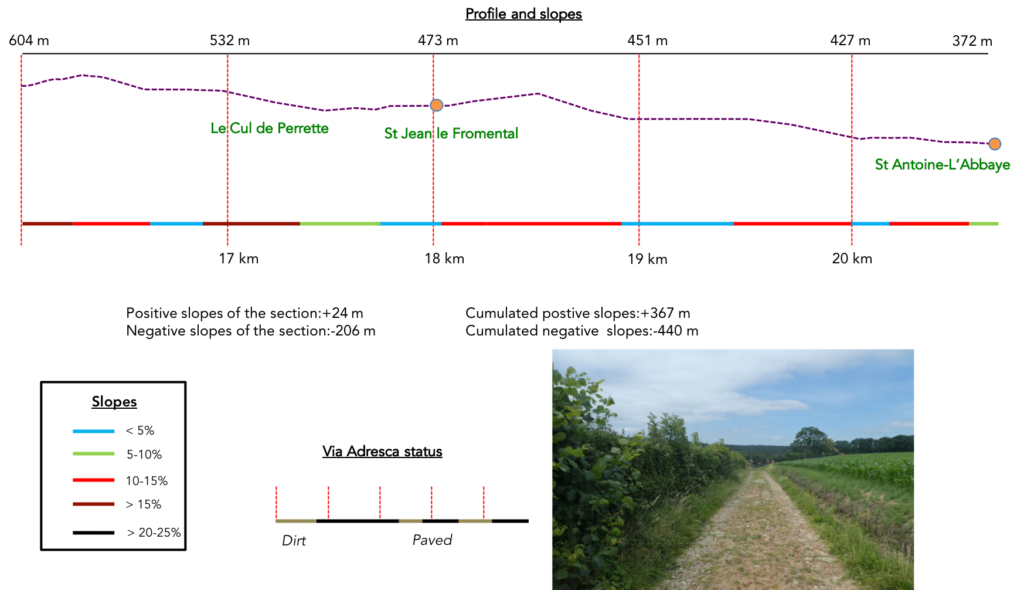

Slope variations of the day (+357 meters /-440 meters) are very reasonable. It is an average stage, where there are however throughout the course some slopes close to 15%, in particular from the start, then in the forest of Gargamelle. It’s again a little more difficult sloping down from the Chambaran plateau towards St Antoine-L’Abbaye.

The stage of the day is to the advantage of the pathways, even if they are very stony:

- Paved roads: 7.5 km

- Pathways: 12.3 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on Via Podiensis. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

Section 1: Ups and downs from a dale to another.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: no difficulty, except the climb to the high plateau with often slopes close to 15%.

| There are not long kilometers to leave the suburb of Marnans. There are not any. The road climbs behind the church towards the forest. But immediately, a pathway slopes up by the Chemin des Essarts towards the undergrowth of Grands Champs. |

|

|

| Here, flows peacefully, in a small dale, the Rapillière brook, a tributary of the Ologne River. You may have imagined, naively, that the pebbles had disappeared during the night. Rest assured, they are always present. |

|

|

| Here, the pathway plays a little with the stream, in the middle of oaks, chestnut trees, hornbeams and beeches. You can even see spruces from time to time, a sign that you are gaining altitude. |

|

|

| Here, the undergrowth is sparse and brush usually dominates. The slope is bearable and when the grass grows, the pebbles are less visible. At least, you can graze it with your feet, avoiding the stones a little. You can then take a last look at Marnans, sunk at the bottom of the dale. |

|

|

| Further up, the pathway leaves the undergrowth, reaches the meadows and a clearing in a slope above 15%. |

|

|

| A little up, the beautiful adobe and rolled pebble farmhouse of Les Essarts, on the edge of the woods, is probably dead for a long time. |

|

|

| Here, the climb is over and a wide dirt road, largely stony, almost clay, runs under the hardwoods. There are still a few oaks, beeches and maples but the chestnut trees will gradually take over and never let go until the end of the road in Ardèche and Haute-Loire. |

|

|

| Further afield, the pathway crosses the high plateau, finds a clearing where the beautiful Charolais graze. These meat cows, very far from their region of origin, are found more and more all over the country. They are a little smaller than the Blanches d’Aquitaine cows. In the region, near the clearings, large ash trees often sway in the wind. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway reaches the place called La Croix de Frère Jacques, in the open countryside, in the middle of clumps of leafy trees. |

|

|

| Here, Via Adresca stays a little longer on the wide stony pathway before finding a road that crosses the high plateau in the meadows and the wheat under tall trees. |

|

|

| On the plateau where the few houses are hidden behind the hedges, livestock farming and some cereal crops are practiced. |

|

|

| A little further on, you’ll leave the tarmac for a wide gravel pathway that runs along the wheat and corn fields. Here, the dirt is ochre, ferruginous to perfection. |

|

|

| In the region, you’ll walk from stony pathways to short stretches of paved road. Tractors prefer tar. |

|

|

| Yet, the passage on the tar is brief before finding a pathway which oscillates, down, up, in the cultures. |

|

|

| At the top of the small hill, it is the return of the road in the middle of the varied cultures which dispute their place with the meadows. |

|

|

| Here, the Galaveyson stream cuts the road. This region is also rich in small ponds that the route, alas, does not visit. |

|

|

| The road soon heads to a gîte and runs to a place called Pré Reynaud, 2 kilometers to Roybon. |

|

|

| You are here on the Feyta road. Remember that the “feytas” are these kinds of morainic high plateaus perched on the great plains of Dauphiné, as you have already encountered in Bièvre-Valloire. Here, Via Adresca continues on tarmac until it crosses the departmental road D156 which goes towards Roybon. There, the route takes the road to Blain Haut. |

|

|

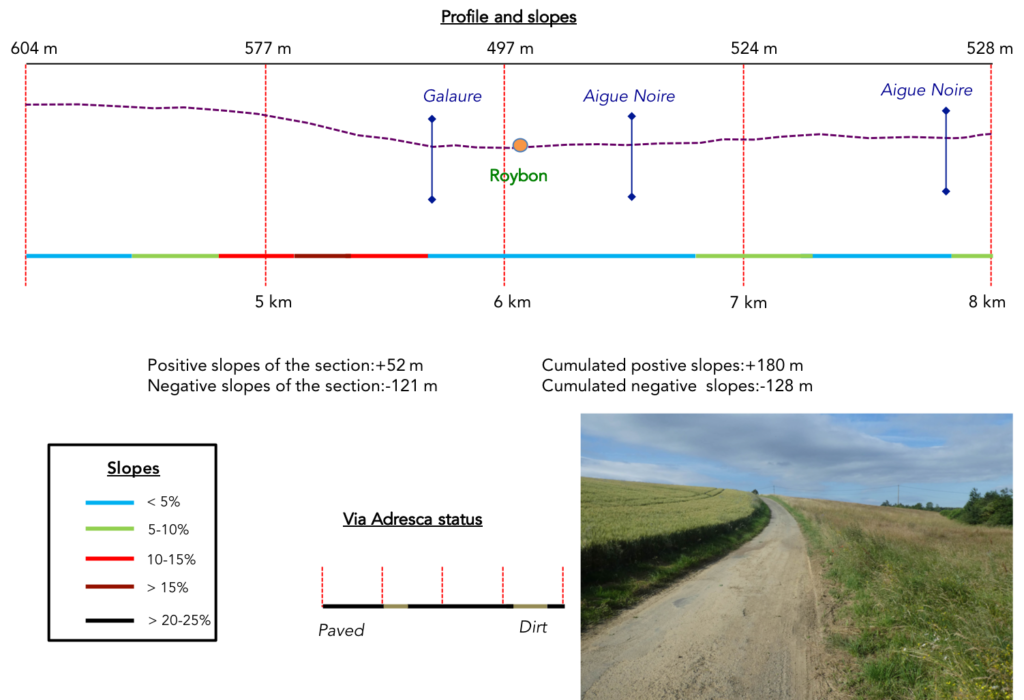

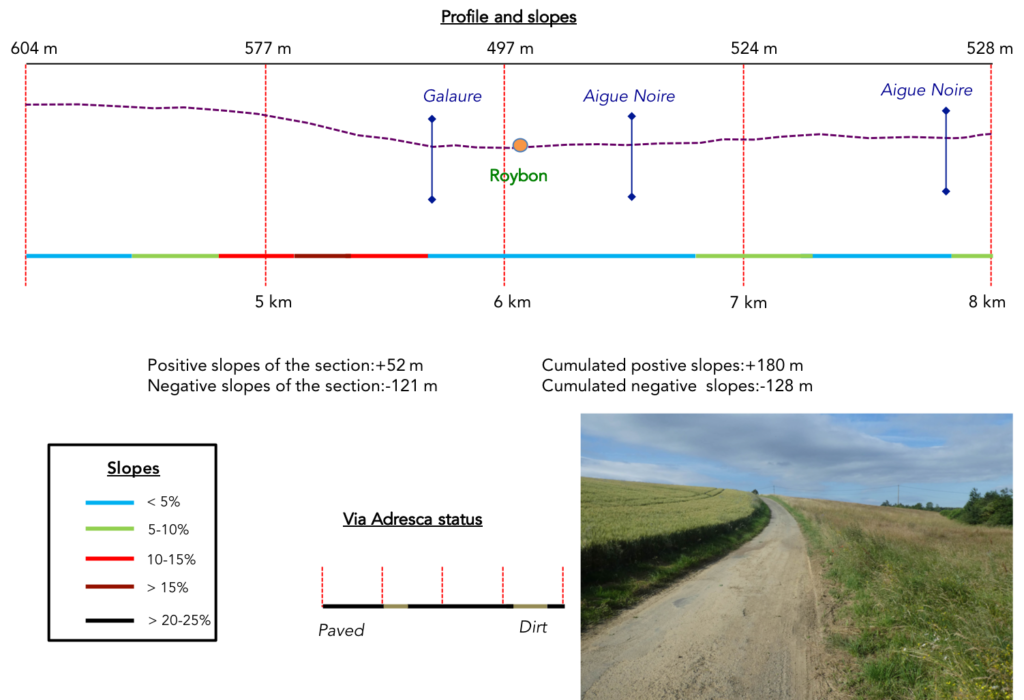

Section 2: A break at Roybon Lake.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| Further on, the road soon gets to a place called Le Blain Haut in the cereals. |

|

|

| Then, it changes repertoire, and continues along the hedges of shrubs and brush. |

|

|

| Shortly after, it joins a pathway that runs into the grass. |

|

|

Below, the gaze plunges over the borough of Roybon.

| And the slope is accelerating on the way. Who says sloping pathway here always says pebbles, and here, they are many. |

|

|

| The forests here are clearly dominated by small, stunted chestnut trees and tall ash trees. |

|

|

| The road then descends into piles of compact brush to join the departmental road which enters Roybon. |

|

|

| Via Adresca arrives quickly at the entrance of the borough. |

|

|

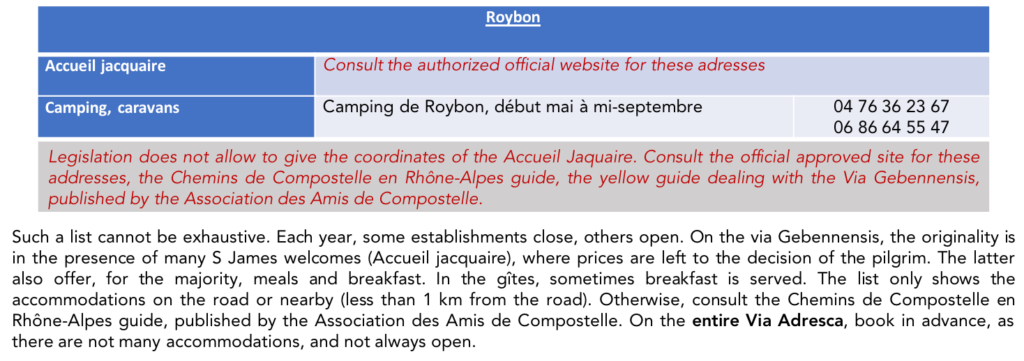

At the entrance, flows the Galaure River, more than a large stream that cascades cheerfully over the stones.

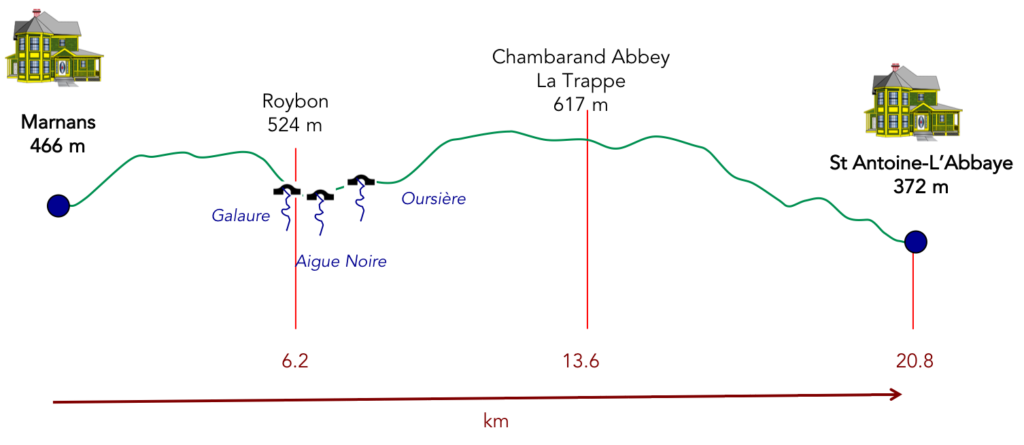

| Roybon (1,300 inhabitants) has all the shops. Also, many pilgrims stop here, if only to pay a short visit to the Statue of Liberty, a miniature replica. The borough is home to many houses made of rolled pebbles, erected between the XVIIIth and XIXth centuries. The neo-Romanesque church, also made of pebbles, was built in the XIXth century. |

|

|

Via Adresca does not go to the center, but takes the direction of the Tourist Office, which is in fact an old train station. And yes, there was, a long time ago, a railway that linked Lyon to St Marcellin, in the Isère valley. The railway passed here, then further to St Antoine-L’Abbaye. This line was called the Voie du Tram. Inaugurated in 1899, it was closed in 1936. Today, it is only a hiking trail. But it will come back one day. It is certain, Macron promised it. It may then be a TGV. Who knows?

| You are here nearly 7 kilometers to the monastery of La Trappe. Via Adresca leaves along the Allée du Lac. |

|

|

| Shortly after, it crosses the Aigue Noire, a stream that hides under the brushwood and empties in the Galaure River. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the road heads towards the lake, an artificial body of water, slightly higher than the borough. |

|

|

| The road runs along the lake where you can practice swimming, fishing or pedal boating in season. |

|

|

| The road leads to a dead end but walkers walk everywhere, right? |

|

|

| A pathway then descends to the campsite, which cannot be said to be in a bad location, at the end of the lake, in a very pleasant setting. |

|

|

| Further afield, a road then bypasses the campsite… |

|

|

| … then crosses the Aigue Noire brook again. |

|

|

| Here, Via Adresca will climb on the road that leads to Chevrières, towards La Trappe, 5 kilometers from here. Here, you’ll leave for a very long and interesting journey in the forests of Chambaran. |

|

|

Section 3: On the Gargamelle side.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: not too difficult, except for the fairly steep climb on the pebbles of the forest of Gargamelle.

| Via Adresca does not follow the road for long. Then, a pathway is looming, it is the Chemin de Gargamelle. But what is Gargamelle, Grandgousier’s wife and Gargantua’s mother, doing in this story? In Provençal, Gargamelle means “throat”. But here, there is no defile, only pebbles. No doubt lovers of Rabelais baptized this pathway as such. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the pathway crosses the Oursière stream. You then enter the Chambaran, a term used to designate a vast expanse of uncultivated land, made up of woods, moors and heather. Despite the fact that you notice the ruts left by the tractors on the way, this part of the forest seems little exploited, the higher you climb. |

|

|

You are quickly confronted with the roughness and the slope of the track. Would Gargamelle have appreciated that her name was used to baptize these pebbles that live on these steep slopes? It is even more striking than the pebbles of the Bièvre, which you have encountered so far. It’s indeed magical here.

| In the forests of Chambaran, as in Dauphiné for that matter, chestnut trees dominate the other hardwoods which make up more than 90% of the species. The second species in number is that of the oaks, first of all rather large pedunculate oaks. For the rest, locusts, beeches, hazelnuts, ashes, and maples complete the panoply. Among the conifers, the spruce dominates and rare are the white firs, the Douglas pines or the Scots pines. |

|

|

| Further up, Gargamelle sometimes drags her feet in sticky mud, but it doesn’t last long. The pathway will exit into the clearing. In the thickets, brambles dominate, but there is also honeysuckle, hawthorn, dogwood, broom and many ferns. |

|

|

| Then the slope gradually decreases in the clearings. In these forests, hunting must be exercised in all likelihood, as proven by the palombières, these watchtowers for hunting wild pigeons at the edge of the wood. |

|

|

| Hikers and pilgrims sometimes shape small cairns. Here, it is not the pebbles that are lacking, but the hikers, rare as the white crows. On the Via Adresca, you will hardly meet anyone. We took this track in the summer, and for more than a week, met a dozen people in all. |

|

|

| Then, at the corner of the wood, in absolute silence, we hear mooing, cries caused by the noise of an engine in the distance. The noise increases and a farmer mounted on his buggy appears in the meadows. In the past, shepherds walked for miles, today they are motorized. |

|

|

| This peasant raises magnificent animals here, cows that eat grass and only grass. Blondes d’Aquitaine, Charolaises, Limousines, Aubracs and the magnificent Salers with their lyre-shaped horns find their happiness here. It’s magnificent the breeding thus conceived by lovers of beautiful cows, but the farmer specifies that in butchery, all these marvels on legs are paid at the same rate as Holsteins who have dragged their teats full to fart for years. What injustice and what absurdity is the commercial world! |

|

|

| At this point, the climb is complete and you are now on the high plateau of Chambaran. You’ll leave Gargamelle and her mystery to continue towards the Secret Wood. The people here have the sense of poetry to baptize their localities. |

|

|

| Here, Via Adresca flattens in a magnificent, peaceful forest, but on clayey, very impermeable ground. The wheels of the tractors have dug ponds where the water is permanently stagnant, even in very dry weather |

|

|

| The situation must have become frozen, because the hikers have created areas of avoidance and dry passage. |

|

|

| And in this pleasant setting, under chestnut trees, oaks and maples, the pathway reaches the Secret Wood. You have to be told that when you walk alone in these vast forests, any direction sign you see them as lifelines. Phew, you are not lost. So here, the pathway takes the direction of the Croix de Mouze, 1 kilometer from here. |

|

|

| Furher on, nothing changes in the forest. It is still soaked, rich in chestnut trees, serene. |

|

|

| Here, sometimes the tall Scots pines make fun of the deciduous trees, to prove to them that they also have a right to exist. |

|

|

| Further afield, just a small clearing to catch a glimpse of the sun, and the pathway returns to the forest. It is still a paradox. In the forest, the pebbles have disappeared, but you are still on the glacial moraines. Have people destoned the woods here or is it the geological reality, the stones sinking on the horizontal land and rolling down the slopes? |

|

|

| The pathway soon gets to the Croix de Mouze, a stone’s throw from La Trappe. |

|

|

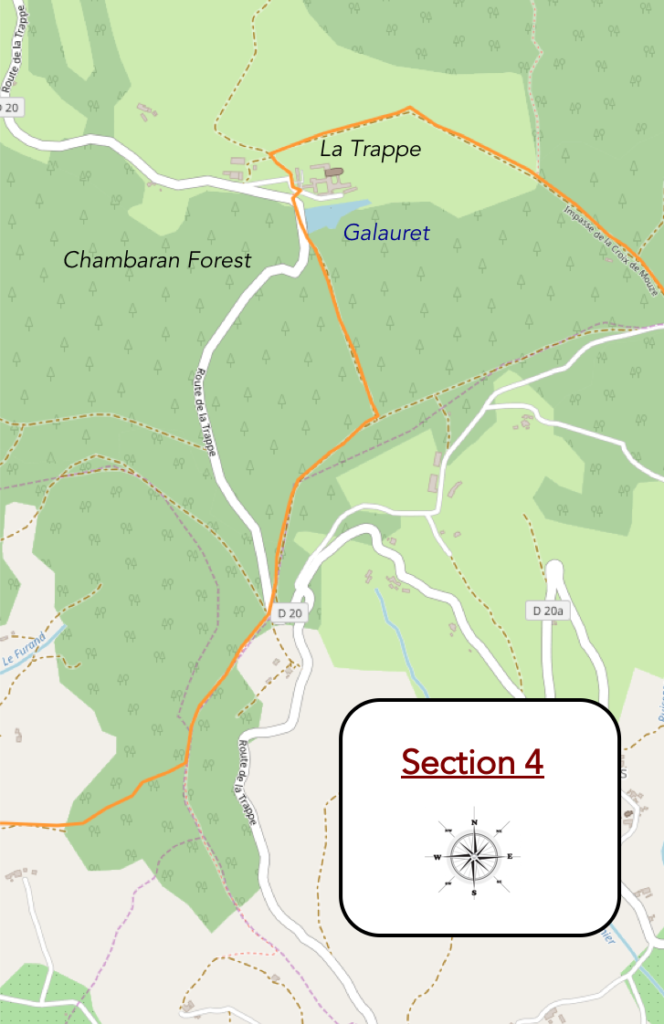

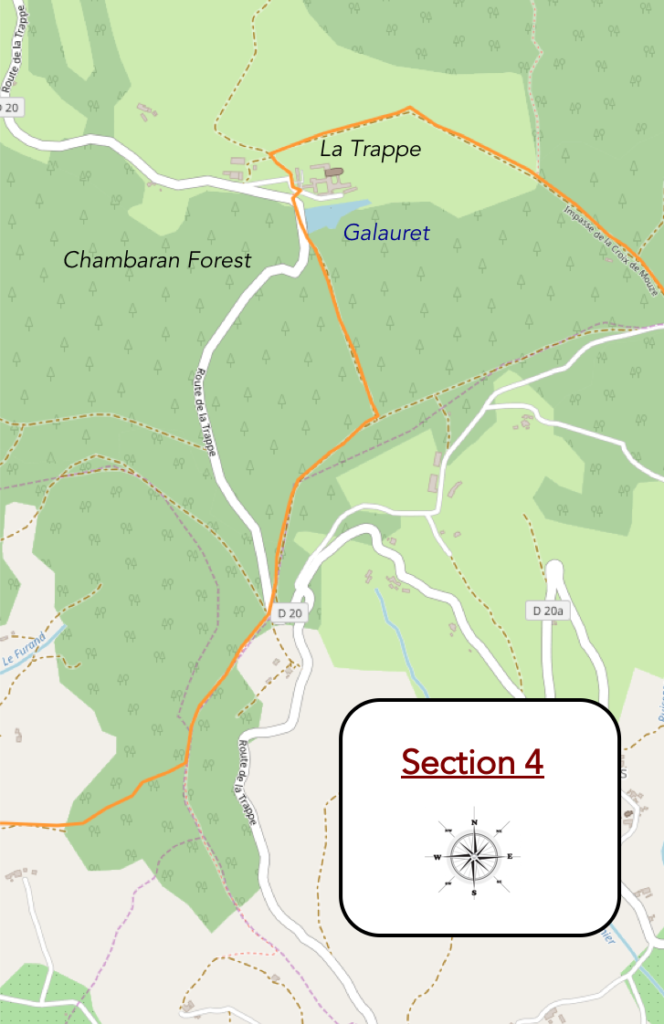

Section 4: Passing through La Trappe and the ups and downs of the Chambaran plateau.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: constant ups and downs, but in a rather comfortable way.

| At the Croix de Mouze passes a small road, but Via Adresca starts off again, at right angles, on a wide pathway in the forest. |

|

|

| At the end of the forest, the pathway gets to a place called Le Mur (Wall) de la Trappe. It is nice to turn towards the 4 cardinal points, no wall here. Is it still a spell of Gargamelle or is it then to notify an old wall which was built to surround the Trappe? |

|

|

| Because, going out into the corn and wheat fields, you can see La Trappe below, in fact the Abbey of Chambarand. |

|

|

| A stony pathway descends along a hedge of brushwood towards the abbey. As soon as the pathways slope down or up in the region, the pebbles reappear. As the subsoil must be an infinite supply of pebbles, no doubt the rain must wash away the soil and cause the pebbles to constantly reappear. |

|

|

| The pathway quickly arrives near the abbey. |

|

|

| Notre-Dame de Chambarand Abbey is a Trappist abbey founded in 1868. It closed in 1903, when the congregations were abolished, and reopened in 1931, when Cistercian nuns, known as Trappinists, settled there and revived the ‘abbey. |

|

|

| A bit of history to situate the Trappists. It was in the XIth century, in the department of Orne, in France, in Soligny-la-Trappe that the movement began, at the abbey of Notre-Dame de la Trappe, commonly called the Grande Trappe. The abbey joined the Order of the Cistercians in 1147. Following the decrease in monastic fervor in the XVIth and XVIIth centuries, the movement was refounded according to a stricter reading of the rule towards the end of the XVIIth century. This is the so-called “strict observance”reform or Trappism, in homage to the abbey that gave birth to it. They are contemplative monks and nuns who live according to the rule of St. Benedict, which governs in detail the monastic life including liturgical modalities, work, relaxation and prayer. In fact, Benedictines, Cistercians and Trappists share this rule, with some nuances.

Then came the French Revolution and this desire to eradicate these useless people. Thus, disappeared several hundred Cistercian monasteries. The Trappists fled to Switzerland, then to Germany and to the countries of the East, to Russia, when the revolutionary armies invaded Switzerland. They were soon driven out of Russia and returned to Germany, England and Belgium. Who does not know and appreciate Belgian Trappist beers? When Napoleon fell, some returned to France. In 1814, they refounded again the Cistercian order of strict observance at La Trappe, from where it radiated throughout the world. At present, the Cistercian Order of the Strict Observance comprises 2,600 monks and 1,883 nuns, distributed respectively in ninety-six abbeys and sixty-six monasteries throughout the world. In 1898, with the restoration of Cîteaux, the original abbey of the Cistercian order, the abbey of La Trappe is no longer the head of the order to which it had given its name.

Notre-Dame de Chambarand Abbey is the last active Cistercian abbey in Isère. The setting is magnificent, with its buildings made of rolled pebbles. The Trappists are known in particular for cheeses and beers. Here, the nuns abandoned the production of beer from the start and the cheese factory disappeared in 2003. 34 sisters live here, from prayers, crafts and products from other monasteries, which they sell in their shop, next to religious objects. |

|

|

| A grassy pathway descends under the Trappe… |

|

|

| …to find a road below the monastery. |

|

|

Further on, Via Adresca runs along the Galauret stream, or rather the Galauret pond. The stream here connects several ponds hidden in the vegetation. On the large pond, reign the peace and serenity of the sisters above.

| Beyond the pond, an initially stony pathway climbs gently into the forest of Bessins. |

|

|

| Then, as you climb, the pebbles disappear as if by magic, under the pines, oaks and chestnut trees. Sometimes the pathway is mired in the ruts of tractors. |

|

|

| The pathway soon heads to the place called Forêt de Bassins, 6 kilometers to St Antoine L’Abbaye. |

|

|

| Here, the foresters have deforested the place and you can then see, in the middle of the slender chestnut trees, more pines and rare ash trees which, like the pines, prefer to flourish in full light rather than in the forests. |

|

|

| Further afield, the pathway momentarily leaves the forest and joins the road to Roybon, which also passes through La Trappe. |

|

|

| You are near the hamlet of La Blache, but the pathway does not go there. Blache is a locality often encountered in the country. The word comes from Gaulish and means “oak”. From then on, these places are often called so, when the copses of oaks have been cleared.

Here, a pathway climbs again towards the forest, skirting the meadows. |

|

|

| The forest is then less dense than before, and the top of the hill has been partially deforested. The dirt hesitates between ocher and dirty gray on a fairly soggy clay pathway. |

|

|

| So, chestnut trees and ash trees, among others, take full advantage of the space that has been offered to them. |

|

|

| One last little pleasure on the pebbles of Chambaran and the pathway comes out of the forest. |

|

|

| Then suddenly, everything changes. You spent most of the day in the forests, it must be said magnificent, and now the universe opens up on pretty and gentle hills. There is of course still undergrowth scattered on the horizon, but the cultures are taking shape between them. When you go through the deep forests alone, which often happens to you, you may breathe better when you go back a little to humans. |

|

|

| Well, humans, that’s a way of saying it. A pathway descends, steep on a small section, otherwise quite wise, between grass and stones from the hill. Not a tree, or almost, only meadows and a little corn. |

|

|

| At the end of the descent, the pathway has almost become sand and arrives on a small road near the Grange Bernier. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the road slopes up to a crossroads where you can reach Renard Castle. |

|

|

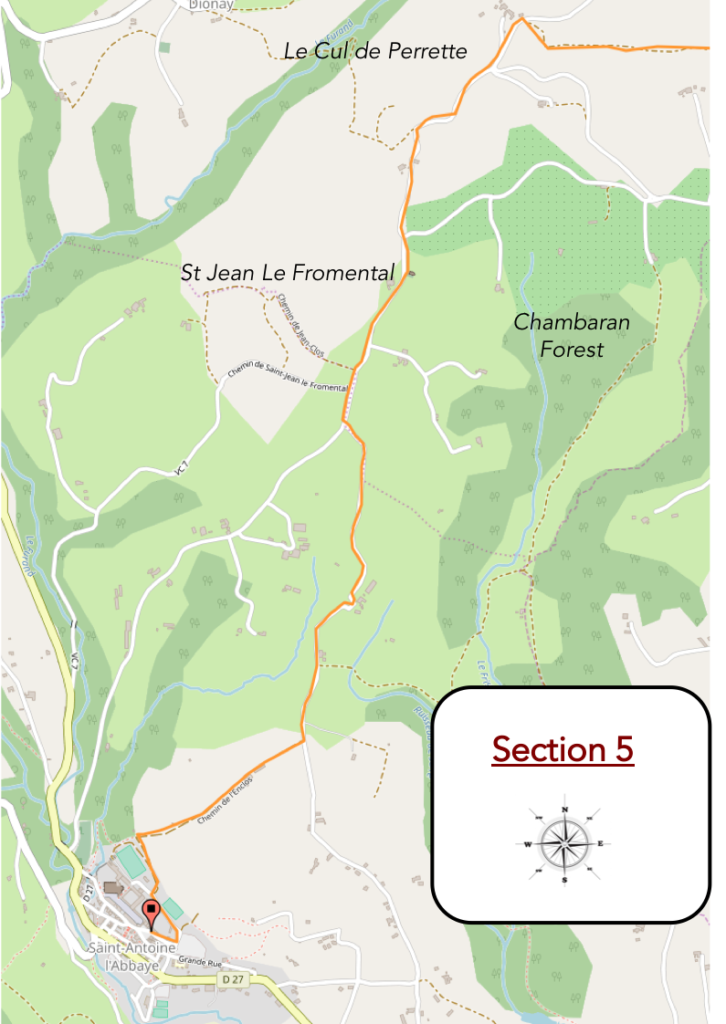

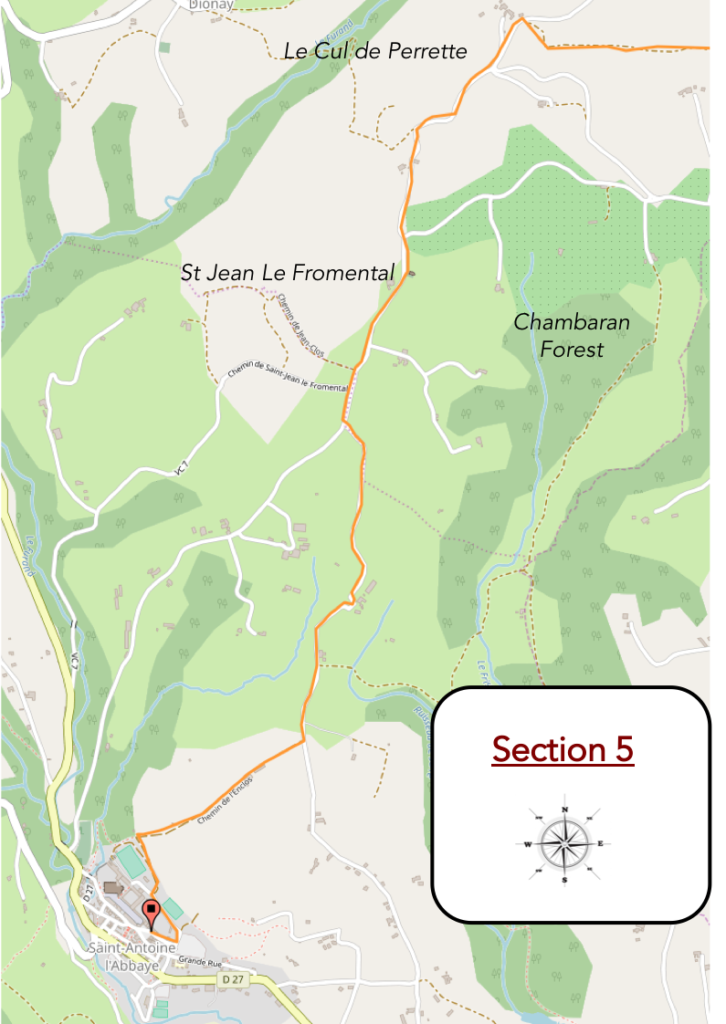

Section 5: On the way to St Antoine-L’Abbaye, another jewel that comes to us from the Middle Ages.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: some beautiful slopes, but especially downhill. You rarely exceed 15%.

| The road continues to climb the hill. Admittedly, the slope is not extreme, short, but nevertheless equipment for the snow is recommended. You are here at less than 600 meters above sea level. |

|

|

| Then, from the top of the hill, the road descends, almost as steep, along the small hills. In front of you, you can see the Vercors region on the horizon, on the other side of the Isère valley. |

|

|

| Further down, the road reaches the place called Le Cul de Perrette. |

|

|

| Further on, it continues to descend in the pleasant countryside among the walnut trees. Here, you are on the outskirts of the walnut estates, where in St Marcellin not only cheeses are made and where the walnut trees are lined up for miles, as if to go to war. |

|

|

| Then, the road slopes up a little… |

|

|

| …to pass in front of the chapel of St Jean-Fromental and its small cemetery. The site is full of grace. The chapel has been known since Roman times, having belonged for centuries to the Antonins of St Antoine-L’Abbaye. The portal is Romanesque, but the chapel has been transformed over time. It is nevertheless classified as a Historic Monument. An old bell from the XVth century still rings the services on Sundays in summer. |

|

|

| Further afield, the road climbs again for almost half a kilometer to reach the top of the hills overlooking St Antoine-L’Abbaye. |

|

|

| At the top of the hill, a gravelly dirt road replaces the tarmac and the pathway drops back down the side of the hill on the other side. |

|

|

| Here, the countryside is bucolic at will. You can even see vines growing there in the middle of walnut trees and large meadows. |

|

|

| Further down, the paved road resumes its rights, meanders and oscillates in the middle of the farms. |

|

|

In the region, small hills follow one another, and the road undulates between them.

| Shortly after, another very slight climb on a road that hesitates between gravel and tar… |

|

|

| …to reach the place called L’Enclos, a stone’s throw from the end of the stage. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the road, in poor condition, passes in front of a fruit and vegetable self-service. |

|

|

| Beyond the farm, a stony pathway begins the descent towards St Antoine-l’Abbaye. |

|

|

| Beyond the farm, a stony pathway begins the descent towards St Antoine-l’Abbaye. |

|

|

| You are immediately struck by the imposing size of the site. |

|

|

| The route runs through the gardens of the abbey, now a large public park. The abbey comprised a large, enormous complex of buildings, including the abbot’s house, the great cloister, the refectory, the libraries, the infirmary, the stable and the gardens. All these places were deeply altered during the XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries, before the decline of the Antonines. |

|

|

| At the entrance to the village, you pass in front of the Tourist Office and the Maison du Tourisme et du Patrimoine. |

|

|

| Passing through a portico erected in a Baroque house, you reach the large rectangular and shaded square, where the cafés and small shops are lost, discreetly, along the annex buildings of the abbey. |

|

|

|

|

| The knight Jocelin de Châteauneuf would have been cured by St Antoine and to thank him would have gone to the Holy Land to bring back his relics. The pope then ordered that the relics be deposited in a place conducive to worship and the monks of the abbey of Montmajour, near Arles, were mandated to guard the relics. In 1088, the monks began the construction of the abbey in St Antoine and deposited there the relics of the saint.

In 1191, a disagreement opposed the Benedictines and the Antonines, who coexist, about the quests. The Antonines would like a chapel of their own, but the Benedictines were against it. Religion has always been a matter of big money and power. The Benedictines then began to enlarge the church, and the Antonines received from the Archbishop of Vienne the possibility of building a church too, but of modest size. So, the Antonines were gradually gaining momentum. At the end of the XIIth century, they already had nine commanderies in the Dauphiné, and even as far as Hungary. At the beginning of the XIIth century, the Antonines became independent of the Benedictines, and the pope imposed on them the rule of the canons of Saint Augustine. They then built a large hospital, which was abandoned and later destroyed. Disputes between the Benedictines and the Antonines then went crescendo. The Benedictines still modified the large church, but their work was stopped when they leaved Saint-Antoine, driven out by armed men raised by the Antonines. They then became masters of the place. They then fight like bitches to find out if the relics of the saint were really here or in Arles. Pope Boniface VIII settled the case, compensated the Benedictines and erected the priory of Saint-Antoine into an abbey in 1297. They then started for more than a century the reconstruction of the abbey, which will thus have several styles of construction. Around 1400 the nave was vaulted. Then, for centuries, the building was modified, following the Wars of Religion, then the French Revolution.

At the end of the XVIIIth century, no French novice entered the Abbey. Order no longer attracted. In 1777, the decline was final, thanks to the disappearance of the “sacred fire” disease. The cloister and the refectory were demolished, and the monastery and its goods transferred to the order of St Jean-de-Jérusalem. The Hospitallers did not stay long in Saint-Antoine. They sold the buildings which were not necessary to them, entrust to the city the hospitals administered by the Antonines. Then, the canonesses of the order settled there and witnessed the dismantling of the wealth of the abbey which they had to leave in 1792. The buildings were sold as national property. The abbey’s treasury waS sealed. In 1826, Jean-Claude Courveille bought part of the abbey for next to nothing and founded a school there. It was not until 1840 that Prosper Mérimée classified the abbey church. Today, offices are occasionally held there, as the church is attached to the diocese of St Marcellin. |

|

|

| Overall, the abbey resembles a work of flamboyant Gothic style, but with other more mixed styles. It is still an imposing and remarkable building. It is obviously classified as a Historic Monument. The carved portal is magnificent. At the back of the very high nave, the altar contains the relics of St Anthony the Healer. The facade, the forecourt, the monumental portal and the grand staircase deserve special mention. |

|

|

| And what about murals? They look older than they actually are. We should also mention the imposing XVIIth century organ, and the Antonine treasury in the sacristies of the church. |

|

|

| From the forecourt of the church, you can see the old village below above the Furand river. |

|

|

| A large part of the village, under the abbey (1 thousand inhabitants), is of medieval structure, with its winding streets, its old houses, some dating back to the XIVth-XVth centuries. Some houses are simple, made of rubble, others half-timbered. In the village you can still see old stalls and markets. |

|

|

|

|

| There are all the shops in the village. We don’t usually advertise accommodations, but if you’ve never had a chance to sleep on top of the trees, you can do so here. The Fontfroide huts are located about 2 kilometers from the town in the forest. To get there, you will be explained over the phone the way to follow and how to reach Via Adresca the next day. But, as the pathway is common at the start, you can see the beginning of the route on the next stage. The huts are in the middle of elongated chestnut barrels. The service here is exceptional. At specific times, you will be served by a rope attached to a pulley your aperitif, your meal, and your breakfast. Strangely, the huts do not move much, except when the wind picks up and then you feel like you are on a boat. |

|

|

Lodging